1. Context

Reading disorder is the most common category among learning disorders. Various studies have shown that about 80% of children with learning disorders also have reading disorders (1). Dyslexic students face major problems in word recognition, spelling, handwriting, reading comprehension, understanding the meaning of words, and reading ability (2). Ortiz et al. (3) reported the prevalence of this disorder to be 5 - 12% using reading performance criteria cited in Peterson and Pennington (2012). Moreover, the prevalence of reading disorders among Iranian students was reported to be 4.58% (4). Considering the psychological and social consequences of the problems caused by differentiating children from normal children in children's lives (5), it is necessary to agree on a suitable solution based on research results.

Despite numerous treatments for dyslexia and various studies on the effectiveness of these treatments, there is still inconsistency between the results of primary studies. Farnia et al. (6) showed the effectiveness of neurofeedback in improving the memory of normal adults. However, according to Alkoby et al. (7) and Marzbani et al. (8), there is no conclusive evidence about the effectiveness of neurofeedback despite its general applications for the treatment of learning disorders, hyperactivity, dyslexia, anxiety, depression, epilepsy, and substance abuse. Cancer and Antonietti (9) studied interventions based on auditory processing about reading problems. They showed that auditory processing interventions, which are part of the group of neuropsychological interventions, have a positive effect on improving dyslexia symptoms, but the results are inconsistent. In a meta-analysis by Galuschka et al. (10) on the effectiveness of treatment approaches for dyslexic children and adolescents, the evidence indicated the lack of efficiency of three types of phonological awareness training in treating dyslexia. The meta-analysis by Lee and Yoon (11) regarding the effectiveness of repeated reading in the fluency of dyslexic students indicates the positive effect of this intervention. A systematic review by Peters et al. (12) on the effectiveness of visual and dynamic attention interventions in dyslexic children's reading showed that visual-perceptual training affects fluency and reading comprehension. However, most of these studies have been limited to pairwise and two-by-two evaluations in which one variable is compared with another. Network meta-analysis has the advantage of using available direct and indirect evidence. Empirical studies have shown that network meta-analysis provides more useful and accurate estimates of intervention effects than direct or indirect estimation alone (13). Network meta-analysis can provide useful information about comparisons between pairs of interventions that would never be evaluated in individual randomized interventions. Simultaneous comparison of all interventions considered in the same analysis allows estimation of their relative ranking on the outcome(s) (13).

2. Objectives

This network meta-analysis aimed to answer these two questions:

- Are neurofeedback, neuropsychology, and phonological awareness group interventions effective in improving dyslexia symptoms?

- Which individual intervention and which group intervention are more likely to reduce the symptoms of dyslexia?

3. Evidence Acquisition

In this research, a systematic review of interventions for dyslexia and a meta-analysis method was used in this review. We included studies in which the age of subjects was under 18 years, the full text was available, the study design was pretest-posttest with a control group, the effect sizes were reported, or the necessary data for calculating the effect sizes existed, and the research design was experimental or quasi-experimental. Accordingly, subjects with other disorders, such as hyperactivity, conduct, and reading disorders, were excluded from the research.

The terms "dyslexia," "reading disorder," "reading disability," "learning disorder," "learning disability," and "LD," or their Persian equivalents, were searched in Scopus, PubMed, Magiran, SID, and Civilica from 1991 to the end of 2021. Since some internal databases did not show sensitivity to the search operators (OR, AND, NOT), the search was conducted only through the keywords of reading disorder, reading disability, dyslexia, and learning disorder to achieve high sensitivity. The search for research sources was limited to English and Farsi. In addition, the reference lists of the selected articles were screened. Initial title screening was done by the first author using Mendeley software and a website. The first and second authors then independently screened the abstracts and entire articles from the initial screening and resolved disagreements using discussion, the results of which were confirmed by the third and fourth authors.

The interventions in this research consisted of neuropsychology, neurofeedback, and phonological awareness interventions, each with several interventions. Neuropsychological interventions comprised cognitive strategies training, metacognitive strategies training, hemisphere-specific stimulation, visual perception skills training, neuropsychology, accuracy training, working memory strategies training, Frostig visual perception, auditory comprehension training, attention training based on the Fletcher program, self-reinforcement, strengthening working memory with computers, perceptual-motor training, computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation, thinking maps training, cognitive games, linguistic games, two hemispheres training, auditory processing training, visual processing training, and non-verbal listening training. Phonological awareness interventions were phonological awareness, phonemic games, cognitive rehabilitation based on phonological awareness, morpheme awareness through games, phoneme-based active memory training, morphological awareness, and phonological training using a robot. Neurofeedback interventions consisted of neurofeedback training, biofeedback training, electroencephalography (EEG), hemoencephalography (HEG), or functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI) of the Loretta type.

4. Data Extraction

At this stage, the full texts of the articles were reviewed. Data were extracted from studies using a form. The extracted data consisted of the name of the author(s), year of publication, data collection method, sample size, mean and standard deviation in the experimental and control groups, outcome(s), participants' gender, age, and education level, and quality of the study. Some of the most important characteristics of the selected studies are listed in Table 1. In the first stage of the search, 8,032 studies were obtained. Finally, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria and removing irrelevant and repetitive studies, 49 articles entered the final stage.

| Study | Year | Country | Research Design | Sample Size | Mean Age | Intervention Type | Outcome | Tools | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baezzat et al. (14) | 2006 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with the control group | 28 | 10 | Neuropsychology | Reading accuracy; reading comprehension | Nasaft et al. reading test (14) | Good |

| Same Siahkalroodi et al. (15) | 2009 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 60 | 9 | Visual perception skills training | Reading comprehension; improving reading performance | Fallahchay reading test (16) | Moderate |

| Yaaghobi and Ahadi (17) | 2005 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 64 | Meta-cognitive strategies | Improving reading performance | Researcher-made reading test (17) | Good | |

| Ghobari-Bonab et al. (18) | 2012 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | 11.5 | Meta-cognitive strategies | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Good |

| Daemi (20) | 2012 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 68 | Meta-cognitive strategies | Improving reading performance; speed of reading | NEMA test (19) | Good | |

| Karimi and Askari (21) | 2013 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Working memory strategies training | Improving reading performance | Azizian and Abedi reading test (22) | Good | |

| Karami et al. (23) | 2013 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 20 | Phonological processing | Speed of reading, reading comprehension, reading accuracy | Sima-Shirazi and Nili-Pour reading test (24) | Good | |

| Vatandoost et al. (25) | 2013 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 20 | 8.5 | Auditory processing training | Improving reading performance | Azizian and Abedi reading test (22) | Good |

| Jadidi Feighan et al. (26) | 2014 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 40 | Neuropsychology | Speed of reading, reading comprehension, reading accuracy | NEMA test (19) | Good | |

| Esfahani et al. (27) | 2014 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Meta-cognitive strategies | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Good | |

| Chupan Zideh et al. (28) | 2015 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Attention training | Improving reading performance | Bdyyan reading test (29) | Good | |

| Yarmohammadian et al. (30) | 2015 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Cognitive strategies | Cognitive strategies | Bdyyan reading test (29) | Good | |

| Mozami Goudarzi et al. (31) | 2015 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Amplification of working memory | Improving reading performance, reading accuracy | NEMA test (19) | Good | |

| Bayrami et al. (32) | 2015 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Neuropsychology | Reading comprehension, reading accuracy | NEMA test (19) | Good | |

| Narimani et al. (33) | 2015 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Phonological processing | Reading comprehension, reading accuracy, speed of reading | Shafiei et al. reading test (34) | Good | |

| Nasri and Karimi Lichahi (35) | 2016 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 40 | Perceptual-motor training | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Good | |

| Hosseinkhanzadeh et al. (36) | 2017 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | 10 | Cognitive rehabilitation | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Good |

| Amrollahi Bioki and Hoosein Khanzadeh (37) | 2017 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Self-learning technique | Reading comprehension, speed of reading | Yarmohammadian et al. reading test (30) | Good | |

| Karami et al. (38) | 2016 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 32 | Meta-cognitive strategies | Reading comprehension, reading accuracy, speed of reading | Fallahchay reading test (16) | Good | |

| Sheykholeslami et al. (39) | 2017 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 40 | 9.2 | working memory training | Improving reading performance | NEMA test (19) | Good |

| Rasouli et al. (40) | 2017 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 40 | Meta-cognitive strategies | Reading comprehension, speed of reading | Sharifi and Raefi reading test (41) | Moderate | |

| Hamidi and Fayazbakhsh (42) | 2016 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 60 | Working memory training | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Good | |

| Akbari et al. (43) | 2019 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 20 | 10 | Working memory training | Reading comprehension | Azizian and Abedi reading test (22) | Good |

| Wang et al. (44) | 2019 | China | Pretest, posttest with control group | 46 | Visual and auditory temporal processing, training | Improving reading performance | Hung reading test (44) | Moderate | |

| Vojoudi et al. (4) | 2017 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 60 | Educational package based on visual-spatial processing | Improving reading performance | Moradi et al. reading test (19) | Good | |

| Pape-Neumann et al. (45) | 2015 | Germany | Pretest, posttest with control group | 20 | 9.8 | Phonological processing | Improving reading performance, reading comprehension | Salzburg reading test (46) | Good |

| Layes et al. (47) | 2020 | France | Pretest, posttest with control group | 44 | 10.25 | Phonological processing | Reading comprehension, reading accuracy | Layes et al. reading test (47) | Moderate |

| Layes et al. (48) | 2019 | France | Pretest, posttest with control group | 40 | 10.32 | Visuomotor-based, intervention | Improving reading performance | Layes et al. reading test (47) | Moderate |

| Wang (49) | 2017 | China | Pretest, posttest with control group | 56 | 8.2 | Phonological processing | Improving reading performance | Hung reading test (44) | Moderate |

| Yaghoubi et al. (50) | 2013 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Visual perception skills training | Improving reading performance, reading comprehension | Fallahchay reading test (16) | Weak | |

| Adib Sereshki et al. (51) | 2017 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Programs based on attention | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Moderate | |

| Sabaghi et al. (52) | 2016 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 36 | 9.5 | Neurofeedback | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Moderate |

| Dehghan et al. (53) | 2018 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Cognitive plays | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Weak | |

| Ladonni Fard et al. (54) | 2017 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | 10 | Linguistic plays program | Reading comprehension, speed of reading | Sima-Shirazi and Nili-Pour reading test (24) | Moderate |

| Rahbar Karbasdehi et al. (55) | 2018 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 27 | 10.11 | Self-regulation strategies | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Moderate |

| Hashemi et al. (56) | 2019 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 60 | Cognitive rehabilitation focused on phonological awareness | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Weak | |

| Safari et al. (57) | 2019 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | 9.66 | Cognitive rehabilitation | Reading comprehension, speed of reading | Nasaft et al. reading test (14) | Weak |

| Naji et al. (58) | 2020 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Phonological active memory | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Moderate | |

| Haghighatzadeh et al. (59) | 2020 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Perceptual-motor training | Improving reading performance | Bdyyan reading test (29) | Weak | |

| Hemati Almdarloo and Tavakoli (60) | 2020 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Programs based on attention | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Moderate | |

| Tikderi and Kafi (61) | 2020 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | 10.5 | Working memory training | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Weak |

| Narimani et al. (62) | 2012 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 31 | 9.5 | Biofeedback | Reading comprehension | Shafiei et al. reading test (34) | Good |

| Azami and Haj Sadeghi (63) | 2017 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Neurofeedback | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Moderate | |

| Soleymani and Vakili (64) | 2016 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Cognitive rehabilitation | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Weak | |

| Gharibi et al. (65) | 2022 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Programs based on attention | Reading comprehension | NEMA test (19) | Good | |

| Kaveh et al. (66) | 2021 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 20 | 8 | Auditory processing training | Reading comprehension | Researcher-made reading test (66) | Good |

| Sabeghi et al. (67) | 2022 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | Neuropsychology | Reading comprehension improving reading performance | NEMA test (19) | Good | |

| Safari et al. (68) | 2020 | Iran | Pretest, posttest with control group | 30 | 9.5 | Cognitive rehabilitation | Reading comprehension, speed of reading | Nasaft et al. reading test (14) | Moderate |

| Pasqualotto and Venuti (69) | 2020 | Italy | Pretest, posttest with control group | 49 | 8.95 | Phonological processing | Speed of reading | Researcher-made reading test (69) | Moderate |

Risk of bias assessment: Bias in psychological interventions is essential due to using different measurement tools (70). This is certainly more evident in the network meta-analysis, where one assumption is the consistency of the studies. Therefore, to assess the risk of bias in the studies, the modified Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool was used (71), which contains five questions:

(1) Are the experimental and control groups adequately matched?

(2) Is the research implementation method clearly stated, for example, in the definition of the research population?

(3) Is the method of selecting research subjects random?

(4) Is the method of random selection stated?

(5) Is the assignment of subjects to experimental and control groups random?

Accordingly, a total score ranging from 0 to 10 is obtained for each study. Scores below 5, between 5 and 7, and 8 or above are considered poor, average, and good quality, respectively.

Statistical analysis: Network meta-analysis was performed using R and R studio software and the "netmeta" package via a random-effects model and frequency approach for the combination of direct and indirect evidence (72). Direct evidence refers to the pooled effect based on randomized studies (as in traditional meta-analysis), while indirect evidence is calculated from the network. For example, the difference between B and C is derived from the difference between A versus B and A versus C.

The network structure was created for both individual and group interventions. Network meta-analysis provides standardized mean difference effect sizes between groups based on both direct and indirect evidence, as well as confidence intervals and P values. Cohen's d interpretation was used to describe effect sizes: 0.2 (small), 0.5 (medium), and 0.8 (large) (73).

The consistency assumption was checked using the P-value statistic from the direct and indirect comparison of the standardized mean difference for each arm connected in the network and visual examination of the graph, and no evidence of inconsistency in the network was found. The analysis also provided information about the probability of each intervention being the most effective using surface under the cumulative rankings curve (SUCRA) values for each intervention and the three groups of interventions. The SUCRA value shows each intervention relative to the hypothetical best intervention (score out of 100) (72).

Evaluating the assumptions of network meta-analysis: One of the presuppositions of network meta-analysis is the examination of heterogeneity. Heterogeneity refers to the fact that there should not be dispersion between the results of studies in pairwise comparisons (74). Therefore, using the I2 statistic, the heterogeneity between the studies was checked, showing a value significant of 91.6. To find the reason for heterogeneity, the I2 value was reduced to 76.6 using the technique of removing outliers. Other factors influencing heterogeneity can root in using different outcome measurement tools with different scoring systems, the presence of a study with a high impact on research, and the different sample sizes of the studies. Therefore, the impact analysis method was used, but it did not reduce heterogeneity. A third step to find sources of heterogeneity was subgroup analysis based on study quality, which did not show evidence of reduced heterogeneity. Another (or the most important) assumption of network meta-analysis, without which it is practically impossible to implement network meta-analysis, is consistency or homogeneity. Therefore, Cochrane's q-test was used to evaluate this assumption, confirming the similarity of direct and indirect comparisons.

5. Results

5.1. Description of Included Studies

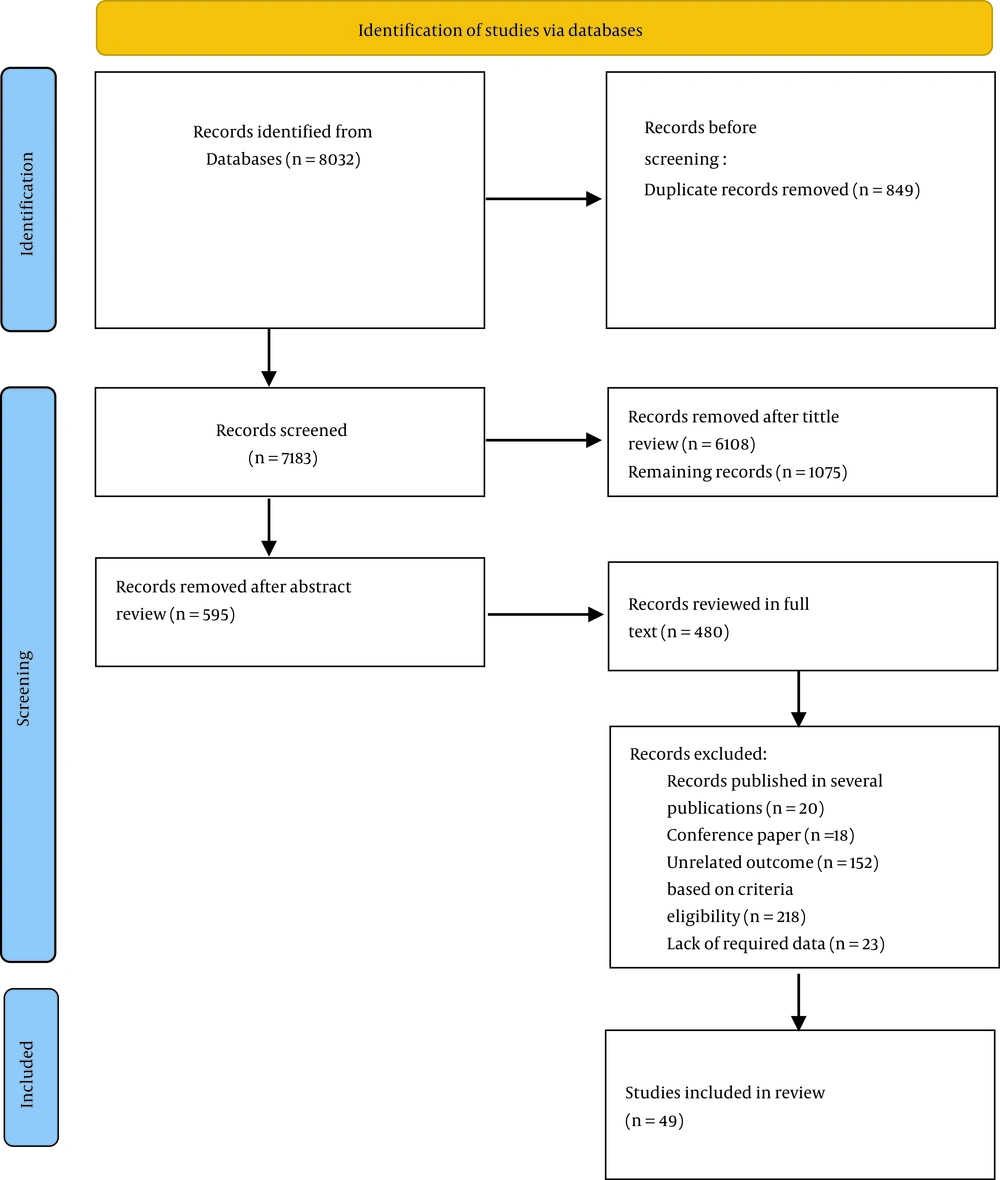

From the databases' search, 8,032 studies were obtained (Figure 1).

After removing duplicate and unrelated items and reviewing research titles and abstracts, 480 full-text studies remained. Finally, using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 49 studies on the outcome of dyslexia (improving reading performance, reading comprehension, reading speed, and accuracy) with 1,741 participants (977 boys (56%) and 764 girls (44%)) were included in the systematic review. There were 48 interventions, control groups, and combined interventions that were classified into 14 classes. Subsequently, they were categorized into three groups for analysis: Neurofeedback-based, neuropsychological-based, and phonological awareness interventions. Of them, 43 studies were conducted in Iran, one in Italy, two in France, one in Germany, and two in China. All the included studies utilized a pretest-posttest design with a control group. Twenty-two studies used (NEMA) test Moradi et al. (19), three studies the reading test of Nesfat et al. (14), three studies the reading test of Fallahchay (16), four studies a researcher-made test, three studies the reading test of Azizian and Abedi (22), two studies the reading test of Sima-Shirazi and Nili-Pour (24), one study the reading test of Yarmohammadian et al. (30), three studies the reading test of Bdyyan (29), two studies the reading test of Shafiei et al. (34), one study the reading test of Sharifi and Raefi (41), two studies the reading test of Hung (44), one study the reading test of Moradi et al. (19), one study the Layes reading test (47), and one study the Salzburg reading test (46) as a study tool. Regarding risk of bias assessment, 26 studies were evaluated as good, 16 as average, and seven as poor (Table 1).

5.2. Analysis

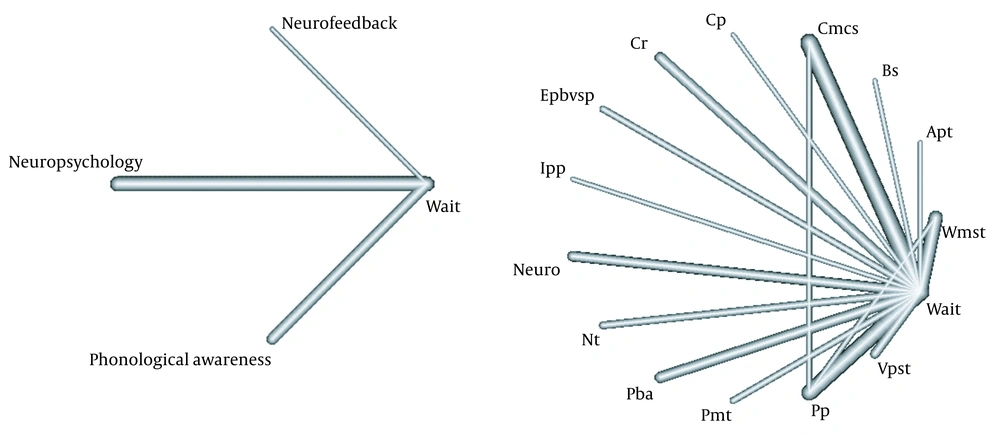

A network map was created with 74 interventions from 49 studies (Figure 2). In the network structure, the lines indicate that two interventions are compared. The width of the lines indicates the number of studies that compared two interventions. The greater the number of studies comparing two interventions, the wider the line. There was no evidence of inconsistency in the models (Q = 1.20, df = 2, and P = 0.55). In other words, consistency means that the relative effect of a comparison (A-B) based on direct evidence is not different from the effect based on indirect evidence (13).

The structure of individual and group interventions. Vpst, visual perception skills training; Cmcs, cognitive and meta-cognitive strategies; Bs, brain stimulation; Wmst, working memory strategies training; Pp, phonological processing; Apt, auditory processing training; Epbvst, educational package based on visual-spatial processing; Nt, neuropsychological treatment; Pba, programs based on attention; Pmt, perceptual-motor training; Cr, cognitive rehabilitation; Neuro, neurofeedback; Cp, cognitive plays; Apt, auditory processing training; Lpp, linguistic plays program; Wait, control group.

The results of network meta-analysis comparisons (effect sizes and confidence intervals) showed that the effect sizes were statistically significant in the direct comparisons of the control group with visual perception skills training, motor perception training, attention-based programs, neuropsychological intervention, spatial perception processing-based training, cognitive games, and cognitive and metacognitive strategies. Moreover, the effect sizes were statistically significant in the indirect comparisons between working memory strategies and perceptual motor training, between neuropsychological intervention and spatial perception processing-based training, between visual perception skills training and phonological processing, linguistic games and spatial perception processing-based training, between phonological processing and motor perception training, attention programs, training based on spatial perception processing and cognitive and metacognitive strategies, between perceptual-motor training and neurofeedback, linguistic games, spatial perceptual processing-based training, cognitive and metacognitive strategies, and auditory processing. Furthermore, effect sizes were statistically significant between attention programs and linguistic games, spatial perception processing training and auditory processing, between neuropsychological intervention and neurofeedback, linguistic games, spatial perception processing-based training, cognitive rehabilitation, and cognitive and metacognitive strategies, between neurofeedback and spatial perception processing-based training, between linguistic games and cognitive and metacognitive strategies, and finally between training based on spatial perceptual processing and cognitive rehabilitation, cognitive games, cognitive and metacognitive strategies, and brain stimulation.

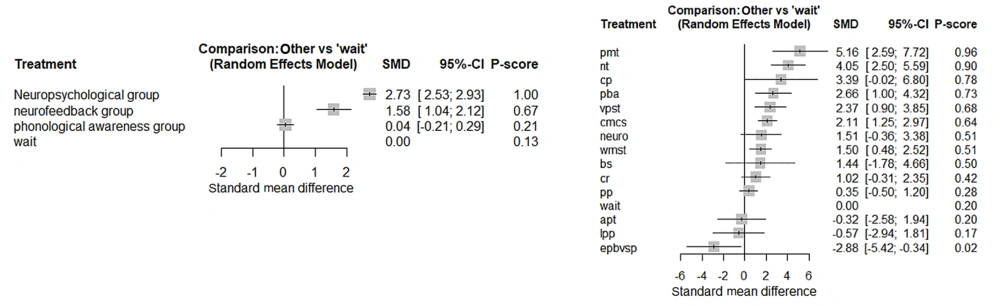

5.3. Ranking of Interventions

In the ranking of interventions, small effect sizes are considered “bad” or “weak.” Individual and group interventions were sorted based on P score, and the intervention or interventions with the largest effect size were placed at the top of the chart. According to the diagram in Figure 3, in individual interventions, the probability of obtaining the first rank in improving dyslexia symptoms for perceptual–motor training is 96%; after that, neuropsychological intervention and cognitive games were in the second and third places, respectively. In the analysis of three-group interventions, the probability that the neuropsychological group intervention will get the first rank in improving the symptoms of dyslexia is 97%. The neurofeedback and phonological awareness group interventions are ranked second and third in phonological awareness, respectively.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study compares the effectiveness of neurofeedback, neuropsychological, and phonological awareness interventions in improving dyslexia symptoms using a network meta-analysis method. In this research, a total of 49 articles were examined. All the studies were assessed in terms of quality and risk of bias. Moreover, network meta-analysis assumptions, including consistency and homogeneity, were considered. Based on the findings, the consistency between the studies was acceptable, but the heterogeneity was high. Sources of heterogeneity were evaluated using three methods, and the reasons were mentioned in the section on heterogeneity.

Regarding the effectiveness of the three interventions, the results showed that the neurofeedback, neuropsychology, and phonological awareness group interventions effectively improve dyslexia symptoms. Based on the P score ranking, the first to third ranks in the individual interventions belonged to perceptual-motor training, neuropsychological interventions, and cognitive games, respectively. These results are somewhat consistent with the research of Peters et al. (12), Cancer and Antonietti (9), and Lee and Yoon (11). This effectiveness is due to the role of motor and perceptual games in creating changes in brain structures and creating changes in executive functions at a young age (75, 76). In-group interventions, neuropsychological group interventions, neurofeedback group interventions, and phonological awareness group interventions were ranked first to third, respectively. Accordingly, it can be stated that neuropsychological interventions are more likely to be effective in improving dyslexia symptoms than neurofeedback and phonological awareness interventions. Due to the high number of interventions in the field of dyslexia, these results can be a good guide for therapists in choosing the best and most effective treatment and intervention for reading disorders.

6.1. Research Limitations

One of the limitations of this research was the disparity in the number of studies in the three groups. Also, we only included studies in which the age of children was under 18 years, the full text was available, the design was pretest-posttest with a control group, the effect sizes were calculated, or the necessary data for calculating the effect sizes existed, and the research design was experimental or quasi-experimental. Accordingly, the subjects who simultaneously had other disorders, such as hyperactivity and conduct disorder, were excluded from the research. The number of initial studies was more in the neuropsychology group and less in the neurofeedback group because, due to the nature of the neurofeedback intervention and its expensive implementation, most studies in the neurofeedback group had single-subject designs and did not meet the conditions for inclusion in the study. Future studies should be carried out considering these limitations. Meta-analysis of single-sample results and conducting neurofeedback research in groups can also lead to a more accurate analysis.