1. Background

Breast cancer is the most important type of cancer among women worldwide, including Iran, comprising 23% of all cancers in this group around the globe and 21.4% in Iran (1, 2). Today, the rate of breast cancer mortality has reduced because of advancements in its screening and treatment methods. Thus, the percentage of patients living with this cancer is increasing (3). An American study showed that 89.2% of women with breast cancer were alive after five years of cancer diagnosis (4). In another study in Iran, 58% of women with cancer were alive after five years of diagnosis (5). According to the national cancer definition, survivor of cancer is defined as a patient with cancer from diagnosis to death (4). The growing number of breast cancer survivors indicates a need for a comprehensive evaluation of different physical and mental aspects to prevent or reduce cancer-related disability.

Quality of life is a good way to comprehensively evaluate patients’ needs, understand success or failure in the treatment process, and prevent further complications of the cancer (4, 6, 7). Multiple tools have been used to determine the quality of life in the active phase of the illness, such as FACT-B and EORTC (6). EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire has been standardized for Iranian women (8). However, this tool cannot evaluate the patient’s quality of life after the treatment process. Thus, a tool for evaluating long-term effects of treatment and illness on physical, psychological , cognitive and sexual conditions is required (9). This tool should cover problems encountered at the end of treatment, such as pain, worry about appearance, and illness relapse (9). Quality of life in the Adult Cancer Survivor (QLACS) questionnaire covers different aspects of patient’s. This questionnaire includes 12 sections, seven of which are related to the general condition of quality of life and five sections to special conditions of cancer patients (3). This questionnaire was first designed to evaluate the quality of life in long survivors of cancer (6). But later studies showed this questionnaire is suitable for short-survivors of cancer as well (3, 4).

2. Objectives

Considering the inability of the available tools to evaluate the quality of life among Iranian cancer survivors at the end of treatment and follow up stages and the ability of QLACS questionnaire, this study was performed to evaluate the properties of the Persian version of QLACS questionnaire among Iranian short-survivors of breast cancer by assessing its validity and reliability.

3. Methods

This was a cross-sectional study. The inclusion criteria included patients diagnosed with stage I, II, or III breast cancer 1.5 - 5 years before starting the study, having finished the active stages of treatment, being in follow up stage, ability to read and understand Persian, and interest to participate. This study was performed at Sayed al-Shohada Hospital clinics, a referral center for cancer patients in Isfahan city in 2017. The eligibility criteria for the center included providing accessibility to a large number of breast cancer survivors in follow up stages. At first, the interviewer explained the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and confidentiality of information. Then, the questionnaire was filled out by patients who were willing to participate.

3.1. Questionnaire

The QLACS questionnaire includes 47 items categorized into 12 domains rated based on a seven-point Likert scale. It consists of seven domains related to the general condition, including positive and negative feelings, cognitive and sexual problems, pain, fatigue, and social avoidance. There are five domains associated with the cancer-specific condition. Its topics include appearance concern, financial problems, recurrence concern, family-related distress, and cancer benefit. In this study, items were rated based on a five-point Likert scale (i.e., never , seldom, sometime, usually, and always) (3).

3.2. Procedure

3.2.1. Translation

In this study, we used the forward-backward method. At first, the original version of the questionnaire was translated to Persian by two native Iranians who were proficient in English and were aware of the research objectives. A review session was held to make the necessary changes and provide the first Persian version of the questionnaire. At the backward step, the Persian version of the questionnaire was separately back-retranslated into English by two bilingual English speakers who was aware of the study objectives. A session was held to compare translations with the original version of the questionnaire. The final Persian version was prepared after making the necessary changes (10).

3.2.2. Face Validity

We used the quantitative method to evaluate the face validity of the questionnaire. Quantitative face validity was established by an impact score. In this method, validity is calculated by multiplying the importance of each item with its frequency. The importance of each item is rated based on a Likert scale ranging from very important (5 score) to unimportant (1 score). An impact score of more than 1.5 is considered suitable. To determine quantitative face validity, the questionnaire was evaluated by a panel of experts, including an internal specialist, a psychologist, three palliative care specialists, and a specialist related to tool making (11).

3.2.3. Content Validity

To evaluate content validity, we used content validity ratio (CVR) for investigating items’ necessity and content validity index (CVI) for items’ relevance.

A three-point Likert scale was used to evaluate the necessity of each item as follows: necessary (3 scores), useful but not necessary (2 scores), not necessary (1 score). The formula of content validity ratio is CVR= (Ne - N/2)/(N/2). In this formula, N is the number of specialists, and Ne is the number of specialists who indicated item necessity. A CVR of more than 0.99 was meaningful and acceptable according to the Lawshe table based on the number of panelists (12).

The relevancy of each item was assessed by a four-point Likert scale as follows: very relevant (4 scores), relevant (3 scores), relatively relevant (2 scores), and not relevant (1 score). The formula of the content validity index is CVI = Nr/N. In this formula, N is the number of specialists, and Nr is the number of specialists who selected relevant or very relevant for each item. A CVI of more than 0.79 was considered suitable. The items with CVI between 0.7 - 0.79 were acceptable after item modification (11).

3.2.4. Construct Validity

We used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) for this section. EFA is a statistical method that identifies the dimensionality of structures by exploring relations between factors and items (13). This method sets the number of questionnaire domains that do not overlap with each other (14). The suitable sample size for EFA is 3-6 cases for every item, according to Cattell (15).

3.2.5. Reliability

We used Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to assess the reliability of the questionnaire. Α value of more than 0.7 was considered suitable (14, 16).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

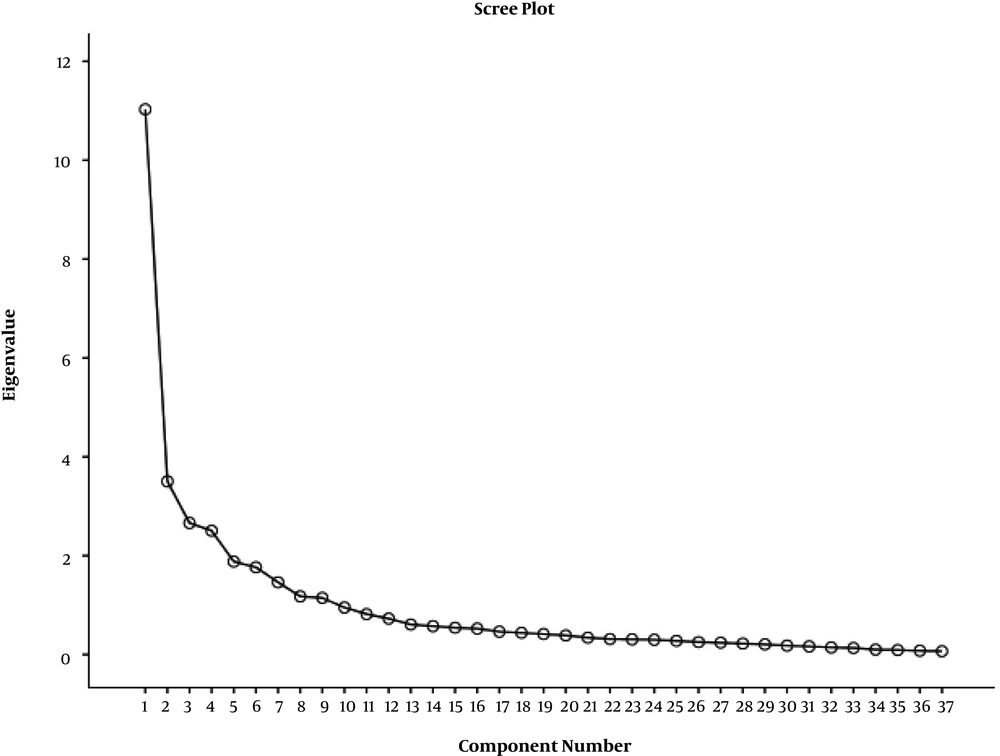

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate face and content validity. EFA was used to determine construct validity. EFA process was started with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test that measures sampling adequacy, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity confirmed that data collected for EFA are suitable (13). A significant value for Bartlett’s test of sphericity is less than 0.05 to continue EFA. Appropriate KMO is more than 0.6 (13). For factor extraction, principle component analysis and varimax rotation were used. Eigenvalue and scree plot graphics were used to determine the number of factors to be extracted. Eigenvalue was considered more than 1 that explained variance percentage of each factor was more than 3% (17). The reliability of the questionnaire was calculated according to Cronbach’s alpha.

4. Results

The panel of experts included six specialists who evaluated quantitative face validity via impact score and content validity via CVR and CVI.

The impact score, CVR, and CVI of the questionnaire items are shown in Table 1. One item was deleted in the face validity stage. This item had an impact score of less than 1.5. Nine items were deleted in the content validity stage. Seven items had a CVR of less than 0.99, and two items had CVI less than 0.7.

| N | Question | Impact Score | CVR | CVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | You had the energy to do the things you wanted to do | 4.8 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | You had difficulty doing activities that require concentrating. | 3.56 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | You were bothered by having a short attention span. | 2.31 | 0.66* | - |

| 4 | You had trouble remembering things | 3.74 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | You felt fatigued. | 4.8 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | You felt happy | 4.8 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | You felt blue or depressed. | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 8 | You enjoyed life | 4.8 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | You worried about little things | 2.64 | 0.66* | - |

| 10 | You were bothered by being unable to function sexually | 4.8 | 1 | 0.66* |

| 11 | You didn’t have energy to do the things you wanted to do | 2.86 | 0.66* | - |

| 12 | You were dissatisfied with your sex life | 4.8 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | You were bothered by pain that kept you from doing the things you wanted to do | 4.8 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | You felt tired a lot | 1.58 | 0.66* | - |

| 15 | You were reluctant to start new relationships | 2 | 1 | 0.83 |

| 16 | You lacked interest in sex | 4.66 | 1 | 1 |

| 17 | Your mood was disrupted by pain or its treatment | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 18 | You avoided social gatherings | 3.87 | 1 | 1 |

| 19 | You were bothered by mood swings | 1.75 | 1 | 0.83 |

| 20 | You avoided your friends | 2.64 | 1 | 0.83 |

| 21 | You had aches or pains | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 22 | You had a positive outlook on life | 4.8 | 1 | 0.83 |

| 23 | You were bothered by forgetting what you started to do | 2.52 | 1 | 0.83 |

| 24 | You felt anxious | 4.66 | 1 | 1 |

| 25 | You were reluctant to meet new people | 1.75 | 1 | 0.83 |

| 26 | You avoided sexual activity | 3.18 | 1 | 1 |

| 27 | Pain or its treatment interfered with your social activities | 4.5 | 1 | 1 |

| 28 | You were content with your life | 4.8 | 1 | 1 |

| 29 | You appreciated life more because of having had cancer | 3.45 | 0.66* | - |

| 30 | You had financial problems because of the cost of cancer surgery or treatment | 3.45 | 1 | 1 |

| 31 | You worried that your family members were at risk of getting cancer | 3.45 | 1 | 1 |

| 32 | You realized that having had cancer helps you cope better with problems now | 2.41 | 0.66* | - |

| 33 | You were self-conscious about the way you look because of your cancer or its treatment | 2.52 | 1 | 0.66* |

| 34 | You worried about whether your family members might have cancer-causing genes | 1.66 | 0.66* | - |

| 35 | You felt unattractive because of your cancer or its treatment | 3.73 | 1 | 0.83 |

| 36 | You worried about dying from cancer | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 37 | You had problems with insurance because of cancer | 2.52 | 1 | 0.83 |

| 38 | You were bothered by hair loss from cancer treatment | 4.66 | 1 | 1 |

| 39 | You worried about cancer coming back | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 40 | You felt that cancer helped you to recognize what is important in life | 1.66 | 1 | 0.83 |

| 41 | You felt better able to deal with stress because of having had cancer | 1.98 | 1 | 0.88 |

| 42 | You worried about whether your family members should have genetic tests for cancer | 0.99* | - | - |

| 43 | You had money problems that arose because you had cancer | 3.32 | 1 | 1 |

| 44 | You felt people treated you differently because of changes to your appearance due to your cancer or its treatment | 2.85 | 1 | 1 |

| 45 | You had financial problems due to a loss of income as a result of cancer | 3.32 | 1 | 1 |

| 46 | Whenever you felt a pain, you worried that it might be cancer again | 3.73 | 1 | 1 |

| 47 | You were preoccupied with concerns about cancer | 2.64 | 1 | 1 |

Impact Score, CVR1 and CVI2 Results Among Breast Cancer Survivors

Construct validity was established on 37 items via factor analysis. In this section, the questionnaire was filled out by 150 patients who met the inclusion criteria (four samples per item). Participants were between 30 - 68 years old. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test confirmed the sampling adequacy for EFA, KMO = 0.844. Bartlett’s test of sphericity, χ2 = 3504.456, P < 0.000 showed that correlations between items were suitable to conduct EFA. Ten factors had eigenvalues greater than one, and the scree plot is shown in Figure 1. Factor analysis extracted 10 factors via varimax rotation, accounting for 75.8% of the total variance (Table 2). Item 31 was transferred to the recurrence-distress factor, and recurrence-distress and family distress factors were merged. Positive and negative feelings factors were merged.

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor | Factor 5 | Factor | Factor 7 | Factor 8 | Factor 9 | Factor 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative/positive feeling | ||||||||||

| 1.You felt happy | 0.219 | 0.232 | 0.682 | 0.081 | 0.077 | 0.039 | 0.262 | 0.036 | 0.229 | -0.071 |

| 2.You felt blue or depressed | 0.247 | 0.272 | 0.542 | 0.063 | 0.081 | 0.198 | 0.191 | 0.044 | 0.35 | 0.014 |

| 3. You enjoyed life | 0.147 | 0.228 | 0.678 | -0.01 | 0.105 | 0.192 | 0.185 | 0.088 | 0.331 | 0.062 |

| 4 You were bothered by mood swings | 0.114 | 0.434 | 0.501 | 0.034 | 0.179 | 0.181 | 0.236 | 0.23 | 0.052 | 0.176 |

| 5. You had a positive outlook on life | 0.193 | 0.181 | 0.773 | 0.046 | 0.188 | 0.078 | -0.011 | 0.074 | 0.145 | 0.214 |

| 6. You felt anxious | 0.411 | 0.422 | 0.438 | 0.175 | 0.053 | 0.188 | 0.227 | 0.02 | -0.023 | 0.031 |

| 7. You were content with your life | 0.166 | 0.041 | 0.757 | 0.036 | 0.23 | 0.072 | 0.152 | 0.241 | -0.2 | 0.119 |

| Distress/recurrence | ||||||||||

| 8. You worried that your family members were at risk of getting cancer | 0.613 | 0.104 | 0.066 | -0.114 | -0.115 | -0.001 | 0.469 | -0.141 | -0.103 | -0.09 |

| 9. You worried about dying from cancer | 0.803 | 0.176 | 0.173 | 0.078 | 0.222 | 0.039 | 0.04 | 0.154 | 0.049 | 0.054 |

| 10. You worried about cancer coming back | 0.804 | 0.054 | 0.125 | 0.212 | -0.026 | 0.053 | 0.075 | 0.108 | 0.138 | 0.081 |

| 11. Whenever you felt a pain, you worried that it might be cancer again | 0.855 | 0.04 | 0.191 | 0.048 | 0.021 | 0.145 | 0.023 | 0.195 | 0.14 | 0.017 |

| 12. You were preoccupied with concerns about cancer | 0.813 | 0.083 | 0.192 | 0.085 | 0.042 | 0.103 | 0.085 | 0.272 | 0.164 | 0.019 |

| Social avoidance | ||||||||||

| 13. You were reluctant to start new relationships | 0.037 | 0.659 | 0.122 | 0.087 | 0.02 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.18 | 0.306 | 0.023 |

| 14. You avoided social gatherings | 0.098 | 0.866 | 0.166 | 0.044 | 0.156 | 0.072 | 0.122 | 0.075 | -0.029 | 0.076 |

| 15. You avoided your friends | 0.09 | 0.876 | 0.17 | 0.069 | 0.144 | 0.146 | 0.012 | 0.135 | -0.016 | 0.039 |

| 16. You were reluctant to meet new people | 0.112 | 0.827 | 0.162 | 0.078 | 0.157 | 0.14 | 0.139 | 0.124 | -0.035 | -0.029 |

| Financial problem | ||||||||||

| 17. You had financial problems because of the cost of cancer surgery or treatment | 0.124 | 0.107 | 0.034 | 0.87 | -0.077 | 0.112 | 0.136 | 0.012 | -0.031 | 0.04 |

| 18. You had problems with insurance because of cancer | 0.043 | 0.05 | -0.01 | 0.738 | 0.126 | -0.083 | 0.028 | -0.039 | 0.161 | -0.002 |

| 19. You had money problems that arose because you had cancer | 0.108 | 0.068 | 0.083 | 0.916 | -0.089 | 0.092 | 0.101 | 0.096 | -0.077 | 0.099 |

| 20. You had financial problems due to a loss of income as a result of cancer | 0.033 | 0.042 | 0.064 | 0.864 | -0.035 | 0.028 | 0.097 | 0.08 | -0.077 | 0.006 |

| Sexual problem | ||||||||||

| 21. You were dissatisfied with your sex life. | 0.047 | 0.151 | 0.115 | -0.031 | 0.89 | 0.003 | 0.059 | -0.052 | 0.078 | 0.105 |

| 22. You lacked interest in sex | 0.059 | 0.134 | 0.139 | -0.044 | 0.85 | 0.126 | 0.046 | -0.088 | 0.14 | 0 |

| 23. You avoided sexual activity | 0.041 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.014 | 0.757 | 0.094 | 0.156 | 0.089 | 0.156 | -0.027 |

| Cognitive problems | ||||||||||

| 24. You had difficulty doing activities that require concentrating. | 0.094 | 0.221 | 0.172 | 0.059 | -0.043 | 0.815 | 0.117 | 0.03 | -0.068 | 0.067 |

| 25. You had trouble remembering things. | 0.032 | 0.041 | 0.1 | 0.048 | 0.081 | 0.87 | 0.077 | -0.02 | 0.22 | 0.133 |

| 26. You were bothered by forgetting what you started to do. | 0.167 | 0.123 | 0.099 | 0.021 | 0.187 | 0.846 | 0.139 | -0.016 | 0.124 | -0.059 |

| Pain | ||||||||||

| 27. You were bothered by pain that kept you from doing the things you wanted to do. | 0.02 | 0.053 | 0.075 | 0.216 | 0.186 | 0.156 | 0.738 | 0.15 | 0.221 | 0.031 |

| 28. Your mood was disrupted by pain or its treatment. | 0.078 | 0.275 | 0.356 | 0.157 | 0.127 | 0.114 | 0.502 | 0.186 | 0.178 | 0.142 |

| 29. You had aches or pains | 0.136 | 0.011 | 0.266 | 0.079 | 0.051 | 0.16 | 0.67 | 0.077 | 0.166 | 0.127 |

| 30. Pain or its treatment interfered with your social activities. | 0.209 | 0.295 | 0.196 | 0.218 | 0.037 | 0.061 | 0.644 | 0.293 | -0.038 | 0.075 |

| Appearance | ||||||||||

| 31. You felt unattractive because of your cancer or its treatment. | 0.179 | 0.329 | 0.122 | 0.019 | 0.021 | -0.01 | 0.056 | 0.794 | 0.024 | 0.01 |

| 32. You were bothered by hair loss from cancer treatment. | 0.239 | 0.033 | 0.115 | -0.012 | -0.338 | -0.031 | 0.283 | 0.612 | -0.163 | -0.022 |

| 33. You felt people treated you differently because of changes to your appearance due to your cancer or its treatment. | 0.224 | 0.195 | 0.163 | 0.128 | 0.041 | 0.009 | 0.16 | 0.757 | -0.037 | 0.03 |

| Fatigue/energy | ||||||||||

| 34. You had the energy to do the things you wanted to do. | 0.182 | 0.074 | 0.178 | -0.085 | 0.246 | 0.088 | 0.115 | -0.059 | 0.786 | 0.154 |

| 35. You felt fatigued. | 0.188 | 0.011 | 0.206 | 0.037 | 0.176 | 0.197 | 0.236 | -0.095 | 0.714 | 0.062 |

| Benefits | ||||||||||

| 36. You felt that cancer helped you to recognize what is important in life. | -0.037 | 0.045 | 0.126 | 0.01 | 0.092 | 0.013 | 0.104 | -0.034 | 0.043 | 0.901 |

| 37. You felt better able to deal with stress because of having had cancer. | 0.116 | 0.054 | 0.101 | 0.107 | -0.02 | 0.106 | 0.058 | 0.06 | 0.115 | 0.856 |

QLACS Factor Analysis Results Among Breast Cancer Survivors

The reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated by Cronbach’s alpha. In this section, the questionnaire was filled out by 20 patients who met the inclusion criteria. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated by the statistical analysis for each factor (Table 3). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were more than 0.7 for all the factors.

| QLACS Questionnaire | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|

| Distress-recurrence | 0.92 |

| Social avoidance | 0.92 |

| Positive and negative feeling | 0.88 |

| Financial problem | 0.93 |

| Sexual interest | 0.90 |

| Cognitive problem | 0.88 |

| Pain | 0.74 |

| Appearance | 0.86 |

| Energy | 0.93 |

| Benefit | 0.87 |

QLACS Factors Reliability Among Survivors of Breast Cancer

5. Discussion

Quality of life evaluation can help to determine the necessary interventions for improving cancer survivor’s quality of life. Among the available tools, we used the QLACS questionnaire because it covered different aspects of life among cancer survivors (3). In this study, after the translation process, we evaluated the face, content and construct validity and reliability of the questionnaire. Overall, 46 items had impact scores of more than 1.5; thus, they were used to evaluate CVR and CVI validity. Nine items were deleted in the content validity stage because of CVR less than 0.99 (seven items) and CVI less than 0.7 (two items). EFA extracted 10 factors from the 37 items. All of the questionnaire domains had a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of more than 0.7.

According to our results, 10 items were deleted in the face and content validity stages. One reason can be the specialist panel that expressed their opinions subjectively about items. However, specialists’ panel were involved in different aspects of cancer patients to reduce this effect. Cultural and environmental differences between countries can be another reason for changing the number of items. Previous studies had not examined QLACS face and content validity.

Based on the results of KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, we could confirm that our data are suitable to conduct EFA. EFA extracted 10 factors from 37 items. The Persian version had two factors less than the original questionnaire. This difference was due to integrating the recurrence-distress and family distress factors and positive and negative feelings factors. The Persian version of the QLACS questionnaire explained 75.8% of the total variance. This incoherence may be due to the number of items used for factor analysis. In this study, after face and content validity stages, 37 items were selected for EFA. Another reason can be a similar understanding of some sentences in our language. Also, the difference in target populations can justify this difference. In this study, breast cancer patients were studied, but the original questionnaire was used for different kinds of cancers (6).

We identified a negative, positive dimension: This factor includes many of the same items as original QLACS questionnaire positive and negative feeling domains except one item ("you were bothered by having a short attention span."). This item was deleted in the content validity stage because could not obtain CVR more than 0.99 according to panelist opinions for necessary aspect. CVR is dependent on the number of panel specialist. In this study, we had a panel, including 6 specialists. In previous studies, CVR was not calculated for QLACS.

We identified a Distress/recurrence dimension: This factor includes items of the distress- recurrence domain and one item from the family-distress domain from the original QLACS questionnaire. Two items from the family distress domain were deleted in this study. The item "you were worried about whether your family members should have genetic tests for cancer" was deleted thein face validity stage because this item could not obtain sufficient importance score according to the panelists’ opinions. "You were worried about whether your family members might have cancer-causing genes" was deleted in the content validity stage.

We identified a social avoidance dimension: This factor included the same items as the social avoidance factor in the original QLACS questionnaire. We also identified a financial dimension: This factor included all the items that were similar to those in the original questionnaire.

We identified a sexual problem dimension: This factor included three items of the sexual problem domain in the original questionnaire. One item (“you were bothered by being unable to function sexually”) was deleted in the content validity stage according to the panelists’ opinions, which could be due to cultural issues.

We identified a cognitive problem dimension: This factor expressed three items of the same factor in the original instrument. One Item ("you were bothered by having a short attention span") was deleted due to CVR less than 0.99.

We identified a pain dimension: This factor was similar to that in the original instrument.

We identified an appearance concerns dimension: This factor included all of the items as the original questionnaire except for “you were self-conscious about the way you look because of your cancer or its treatment”. This item was deleted because it was not relevant enough according to the panelists’ opinions.

We identified a fatigue/energy dimension: This factor expressed two items from the original instrument. Items “you did not have the energy to do the things you wanted to do” and “you felt tired a lot” were deleted because of CVR less than 0.66.

We identified a benefit dimension: This factor included two items from the original questionnaire. In this study, two items were deleted from the benefit factor from the original questionnaire. Items “You appreciate life more because of having had cancer” and “You realize that having had cancer helps you cope better with problems now” were deleted because of CVR less than 0.6 (6).

Previous studies did not apply EFA for the QLACS questionnaire, which limited our comparisons (3, 9). However, EFA should be used in the early stages of developing or correcting an instrument (13).

In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was used to evaluate internal consistency. The range of Cronbach’s alpha was between 0.74 - 0.93 for different factors of the questionnaire. The range of Cronbach’s alpha for the original questionnaire factors was between 0.72 - 0.91 that was similar to our results. In the Spanish version of the questionnaire, the range of Cronbach’s alpha was between 0.73 and 0.87 (6).

Our results supported that the Persian version of the QLACS questionnaire has suitable properties for evaluating the quality of life among short survivors of breast cancer.

5.1. Limitations

There were some limitations to this study. According to the specialist panel’s suggestions, face and content validity were determined so it can change by changing the specialist panel. For further studies, we suggest a panel group with a greater number of specialists to reduce this effect. In this study, we used EFA for construct validity. For further studies we recommend confirmatory factor analysis for confirming our findings.

5.2. Conclusion

According to the results, the Persian version of the QLACS questionnaire has optimal properties for assessing the quality of life among Iranian short-survivors of breast cancer.