1. Context

The term ‘non-technical skills’ (NST) has been derived from the guidelines developed by European Joint Aviation Authorities in 1990, known as Crew Resource Management (CRM), in response to the then-emerging importance of teaching skills that enabled airline pilots to manage the supply of services in critical emergencies and maintain flight safety (1-3). These skills have attitudinal, behavioral, and cognitive characters and are known as human factors, soft skills, or NTS (4). A group of psychologists believes that NTS should not be regarded as equivalent to human factors because NTS, including situation awareness, decision-making, leadership, teamwork, communication, and stress and fatigue management, are personal, social, and cognitive skills that complement technical skills and have a major role in the personnel's effective, safe, and efficient performance of tasks. This is while human factors are only associated with the cultural characteristics ruling the workplace, including relationships with patients and colleagues, teamwork, reflection, and creation of a balance between work and life (5-7). By another definition, NTS refers to non-clinical skills, which include 10 key skills, namely communication skills, critical thinking, emotional intelligence, ethical conduct, rational curiosity, organizational skills, resilience, personal promotion, teamwork, and occupational commitment (8). Undoubtedly, in any job, determining necessary NTS requires the careful identification of delegated responsibilities and the understanding of workplace features and conditions and organizational culture in place (9).

The operating room environment is a unique clinical setting with characteristics such as diverse, sophisticated technological equipment and tools, innovative techniques in performing various procedures, restrictions on traffic, stressful emergencies, work in a busy and congested environment, and the need for teamwork along with attention to patient safety. Identifying the components associated with non-technical cognitive and behavioral skills in this setting can have an effective role in providing an efficient skill instructional model in the curricula of all surgical team members (10).

The results of previous studies have shown that poor NTS in the operation room weakens the level of technical adeptness, leading to unwanted and unfavorable postoperative complications and outcomes (11, 12). For example, surgeons’ lack of attention and poor communication with members of the surgical team has accounted for 43% of surgical errors (13). Therefore, NTS training can lead to improved acquisition of technical skills, which ultimately improves the quality of services provided, reduces medical errors, and enhances patient safety (14-18). Although teaching such skills still has no formal place in the surgical curricula of many universities, in the ACGME core competencies, more than half of the 210 points are designated to medical competencies about NTS, including communication and inter-professional skills, professionalism or professional mannerism, and system-based performance, while interpersonal and communication skills are emphasized as one of the core competencies of surgeons (19, 20). Over the last two decades, the importance of NTS for medical students to acquire professional competencies has encouraged researchers and authorities of educational systems to develop and introduce effective models for teaching and evaluating the NTS (21).

The results of a systematic review study conducted by Dietz et al. (2014) on the models introduced for registering behavioral skills in medical sciences showed that 75% of these models were designed for specialized clinical fields, with the highest number in the fields of surgery and anesthesia (45%) and the rest in trauma and resuscitation (30%) in adults and infants, which indicates the importance of teaching and evaluating these skills in the operating room environment (22). Given the complexity and unique conditions of the operating room and the need for teamwork in such an environment to maintain patient and personnel safety, identifying NTS and models developed for their teaching and assessment can improve the current curricula of surgery and anesthesia by offering a valid model. The present study was conducted to critically review the tools developed to assess NTS among surgical team members in the environment of the operating room.

2. Evidence Acquisition

Since the present study aimed to identify and assess the weaknesses and strengths of the tools developed to assess NTS in surgical team members in the operating room environment, a critical review method was considered appropriate for the study. The critical review method proposed by Carnwell and Daly was used, and the study followed their framework (23). Given that the main focus of the study was on identifying tools and models developed to assess NTS according to a systematic method, the literature search was based on the PRISMA guidelines (24). A search was carried out for relevant articles and documents published from 1999 to 2019 in databases including PubMed, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and Scopus using the following English keywords: "Human factors" OR "soft skills" AND "non-technical skills in operating room” OR “non-technical skills of surgical team" OR "non-technical skills of the scrub nurse" OR "non-technical skills of the surgeon” OR "non-technical skills in anesthesia”.

3. Results

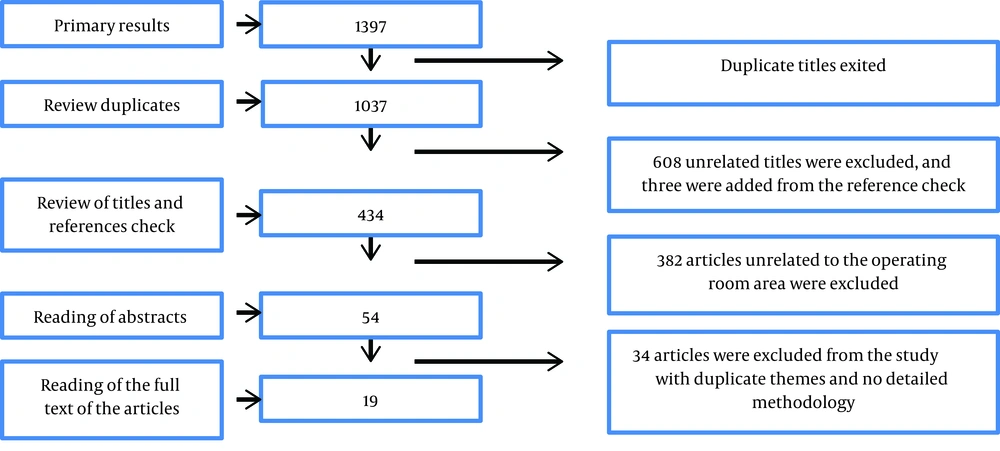

A total of 1,397 articles were extracted from the first stage of the search, with 360 being repetitive. The titles of the remaining 1037 articles were assessed by two of the researchers in terms of relevance to the study objectives, which resulted in the selection of 431 articles. At this stage, the references provided by these articles were manually checked, and three new articles were added to the previous list. The abstracts of these 434 articles were then translated and reviewed by the two researchers, and any doubts about the selection of an article were resolved by seeking the opinion of a third researcher for final confirmation. Ultimately, 52 articles were selected based on their relevance to the subject of ‘assessment tools for NTS in surgical team members’, and were fully reviewed. After excluding the repetitive articles dealing with the same tool and those with a poor methodology, 19 articles were finally approved (Figure 1).

The review of these 19 final articles led to the identification of 13 NTS assessment tools that were related to the operating room environment, which had been developed and used specifically for assessing NTS. Carnwell and Daly proposed four stages in the development of critical reviews, including (1) Defining the scope of the review, (2) Identifying and selecting the sources of relevant information, (3) Organizing the results of the review into categories, and (4) Concluding and informing further studies (23). Accordingly, the subject of ‘non-technical skills assessment tools’ was critically evaluated as the main category in two subcategories, namely individual and group assessment tools for different people and groups working in the operating room, as shown in Table 1. Table 2 presents the chronology of the development of NTS assessment tools over the last two decades.

| No. | Non-Technical Skills Evaluation Tools | Surgical Team | Anesthetic Practitioners | Anesthesiology Students | Nurse Anesthetists | Scrub Nurses | Anesthesiologists | Surgeons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anaesthetists non-technical skills (ANTS) | * | ||||||

| 2 | Anaesthetists non-technical skills (OTAS) | * | ||||||

| 3 | Non-technical skills for surgeons (NOTSS) | * | ||||||

| 4 | Revised non-technical skills (Revised NOTECHS) | * | ||||||

| 5 | Scrub practitioners’ intraoperative non-technical skills (SPINTS) | * | ||||||

| 6 | Oxford non-technical skills (Oxford NOTEHS) | * | ||||||

| 7 | Nurse anaesthetists’ non-technical skills (N-ANTS) | * | ||||||

| 8 | Oxford non-technical skills II (Oxford NOTECHS II) | * | ||||||

| 9 | Anaesthetic non-technical skills for anaesthetic practitioners (ANTS-AP) | * | ||||||

| 10 | Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSANTS) | * | ||||||

| 11 | Surgical decision-making rating scale (SDM-RS) | * | ||||||

| 12 | Surgeons' leadership inventory (SLI) | * | ||||||

| 13 | Anaesthesiology students’ non-technical skills (AS-NTS) | * |

| No. | Authors | Country and Year of Tool Development | Assessment Tool | Kind of Measurement | Scoring | Assessment Attribution | Target Group | Participants in Tool Development | Validity | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fletcher et al. | 2000, Scotland | ANTS | Scale | Score: 0 - 4 | Task management, Team working, Situation awareness, Decision-making | Anesthesiologists | Anesthesiologists and Psychologists | Content validity | Good Internal consistency |

| 2 | Healey et al., Sevdalis et al. (25, 26) | 2004, London | OTAS | Checklist, scale | Score: 0 - 6 | Cooperation, Leadership, Coordination, Awareness, and Communication | Surgical team members | Surgical residents, human factor experts, psychologists, expert surgeons, nurses, anesthesia supervisors, anesthesiologists, and scrub nurses | Construct validity Content validity | ICC = 0.4 - 0.9 |

| 3 | Yule, R. Flin, S. et al. (27) | 2005, Scotland | NOTSS | Scale | Score:1 - 4 | Situation awareness, Decision-making, Task management, Leadership, Communication and teamwork | Surgeons, assistant surgeons, and scrub nurses | Consultant surgeons, surgical students, surgical care practitioners, scrub nurses, anesthesiologists, clinical supervisors, and Professor Rhona Flin | Construct validity Content validity Face validity | ICC = 0.8 |

| 4 | Sevdalis et al. (26) | 2008, London | Revised NOTECHS | Scale | Score: 1 - 6 | Cooperation, Leadership and Managerial, Situation Awareness and Vigilance, Decision-making, Communication and Interaction | Surgeons, anesthesiologists, and scrub nurses | Surgeons, anesthesiologists, and scrub nurses | Content validity | ICC = 0.78 - 0.88 |

| 5 | Lucy,Michel,flin, et al. (28) | 2008, Scotland | SPINTS | Scale | Score: 1 - 4 Poor-Good | Situation awareness, Communication and teamwork, Task management | Scrub nurses | Scrub nurses and psychologists | Content validity | ICC = 0.7 |

| 6 | Suman et al. (29) | 2008, Canada | SDM-RS | Scale | Score: 1 - 5 | Decision-making | Surgeons | Surgeons | Content validity | Cronbach's alpha = 0.98 |

| 7 | A. Mishra, et al. (30) | 2009, United Kingdom | Oxford NOTEHS | Scale | Score: 1 - 4 | Leadership and management, Teamwork and cooperation, Problem-solving and decision-making, Situation awareness | Surgeons, anesthesiologists, and scrub nurses | Surgical residents, operating room nurses, and anesthesiologists | Construct validity Content validity Face validity | High |

| 8 | LYK-Jensen (31) | 2011, Denmark | N-ANTS | Scale | Score: 1 - 5 | Situation awareness, Decision-making, Task management, Team working | Nurses Anesthetists | Anesthesiology nurses, anesthesiologists, surgeons, scrub nurses, clinical supervisors, and educational supervisors | Content validity | High |

| 9 | Sarah Henrickson (32) | 2013, Scotland | SLI | Scale | Score: 1-4, Poor = Good | Maintaining standards, Managing resources, Making decisions, Directing, Training, Supporting others, Communicating, and Coping with pressure | Surgeons | Surgeons and psychologists | Content validity Face validity | Inter-rater agreement = 0.7 |

| 10 | Robertson et al. (33) | 2013, The United Kingdom and the USA | Oxford NOTECHS II | Scale | Score: 1 - 8 | Leadership and management, Teamwork and cooperation, Problem-solving and decision-making, Situation awareness | Surgeons, Anesthesiologists, and scrub nurses | Human factor experts, psychologists, expert surgeons, anesthesia experts, anesthesiologists, scrub nurses | Construct validity Content validity Face validity Criterion validity | High Inter-rater agreement |

| 11 | Nicolas J et al. (34) | 2014, Canada. | OSANTS | Scale | Score: 1 - 5 | Decision-making, Leading, Directing, Managing, Coordinating, Professionalism, Situation awareness, Teamwork, Communication | Surgeons | Surgeons | Content validity | Cronbach's alpha = 0.8 |

| 12 | John Rutherford,flin (35) | 2015, Great Britain and Ireland | ANTS-AP | Scale | Score: 1-4, Poor = Good | Situation awareness, Teamwork and communication, Task management | Anesthetic Practitioners | Consultants, experts anesthesiologist assistants, anesthesiologists, faculty members and trainers | Construct validity Content validity | High Cronbach's alpha |

| 13 | Parisa Moll-Khosrawi, Anne Kamphausen (36) | 2019, Germany | AS-NTS | Scale | Score: 1-5, Very poor-very good | Planning tasks, Prioritizing and problem-solving, Teamwork and leadership, Team orientation | Anesthesiology students | Psychometric psychologists anesthesiologists | Content validity | ICC = 0.89 |

4. Discussion

According to the results of this study, six of the above-mentioned tools were developed under the supervision of Dr. Rhona Flin, a professor in the School of Psychology, the University of Aberdeen, which is considered one of the strengths of the development process of these tools due to the attention to the psychometric aspects of the tools (3, 27, 32, 35, 37). Five of these tools were developed in Scotland (3, 27, 32, 35, 37), one in Denmark (31), one in Germany (36), two in Canada (29, 34), and five in the UK (26, 30, 31, 33, 35), which can limit their generalizability, given the different context of operating rooms in developed and developing countries, particularly since a job analysis was used in the process of development of these tools, which reduces their generalizability. The reason is that, for example, in some countries, scrub nurses are operating room technologists who perform the same duties as an assistant surgeon in the surgical team; also, the role of anesthesia nurses differs widely in different countries.

4.1. Scrub Nurses’ NTS Assessment Tools

SPINTS is a specialized tool for assessing NTS in scrub nurses. Scrub nurses are among the core sterile members of the surgical team who assume various responsibilities in different operating rooms according to their job description. The development of this tool dates back to over 10 years ago, and several researchers around the world have used it to assess scrub nurses' NTS and confirmed its validity and reliability. This tool was developed by a tool development team at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland and assesses four aspects of NTS in scrub nurses, including Situation awareness, Communication and teamwork, and Task management (28, 37-39). Since the process of tool development has been based on the occupational analysis of scrub nurses in these countries, the generalizability of these skills to surgical technologists is not possible in countries with similar jobs to scrub nurses, who assume the role of surgeon's first assistant due to the lack of a designated surgeon's first assistant in most centers, especially at non-university centers. For example, in critical situations, scrub nurses may have an important role in stress management in stages such as exposure and homeostasis even though this category has not been foreseen in the four categories extracted for scrub nurses based on SPINTS.

4.2. Anesthesia Group’s NTS Assessment Tools

In the anesthesiology group, ANTS was developed in 2000 as a specialized NTS assessment tool for anesthesiologists and has since been used in several studies, including studies by Flin in 2011, Jirativanont in 2017, and Boet et al., as a valuable tool for assessing NTS in anesthesiologists (3, 40, 41). Besides ANTS, N-ANTS was developed in 2014 to assess anesthesiology nurses (29), ANTS-AP in late 2015 to assess anesthetic practitioners (35), and AS-NTS in 2019 (36) to assess anesthesiology students. Since anesthesiology nurses have a similar job description to anesthesiologists in some centers and induce anesthesia independently, the NTS is approximately the same in these two tools, such that the four main categories of NTS include task management, team working, situation awareness, and decision making. Nonetheless, in ANTS-AP, due to the lack of direct responsibility for the patients, the decision-making skill has been removed from the four main skills, and only three skills (situation awareness, teamwork and communication, and task management) are assessed by the tool. Although the categories extracted in N-ANTS and ANTS largely match due to the similarity of the duties of anesthesiologists and anesthesiology nurses in most countries, given the particular conditions of patient admission to operating rooms in different countries in terms of structural and managerial differences, stress management may be among the main categories of NTS in the anesthesiology group that has not been included in this tool. Moreover, the decision-making skill has not been foreseen in ANTS-AP, while in operating rooms admitting large numbers of patients concurrently, the anesthesiologist cannot be simultaneously present for all the admitted cases, and assistants should also have the ability to make correct decisions. AS-ANTS also emphasizes the assessment of NTS, such as planning tasks, prioritizing and problem-solving, teamwork and leadership, and team orientation, which requires further contemplation due to differences in anesthesiology students' education in different countries. In this tool, the issue of the students' ability to communicate with patients, and the medical team appears to have been overshadowed by teamwork.

4.3. Surgeons’ NTS Assessment Tools

In the category of tools developed for surgeons, NOTSS was the first tool developed to assess the four main skills (situation awareness, decision-making, leadership and communication, and teamwork) (27, 42, 43). The validity and reliability of this tool were confirmed in studies conducted by Dedy et al. in 2016 (44), Jung et al. in 2018 (42), Rao et al. in 2016 (45), and Yule et al. in 2015 (7). OSANTS is another tool developed in 2014 to specifically assess surgeons’ skills. Compared to the previous tools, which mostly assess the four main skills (situation awareness, decision-making, leadership and communication, and teamwork), this tool assesses other aspects of NTS, including professionalism, management, and coordination (34). In a few years, researchers conducted several trial studies and confirmed the effectiveness of this tool in assessing residents' learning (44, 46). The categories in this tool appear to agree with the competencies determined in ACGME. As discussed in the previous sections, the majority of the NTS assessment tools for surgical and anesthesia team members in the operating room have considered some cognitive, behavioral, and attitudinal skills together, with the most prominent being situation awareness, communication and teamwork, leadership and management, decision-making, and problem-solving. Nevertheless, some researchers have only discussed the assessment of one of these skills and have developed tools consistent with the given skill, including SDM-RS, which only assesses surgeons' decision-making skills (29), or SLI, which assesses management skills under subjects such as maintaining standards, managing resources, making decisions, directing, training, supporting others, communicating, and coping with pressure (32). Although focusing on only one competency can enable a more valid assessment, due to the key role and effectiveness of other aspects of NTS, including communication and situation awareness skills, in decision-making, tools that assess these skills together seem to have a greater validity in determining surgeons' competence.

4.4. Surgical Team Members’ NTS Assessment Tools

Based on the results presented in Table 1, given the requirement for teamwork in the operating room and the assessment of members’ performance as the surgical team, four of the identified tools concurrently assess the NTS of three main surgical team members, namely the surgeons, anesthesiologists, and scrub nurses (25, 26, 30, 33, 47). OTAS (25, 47), Revised NOTECHS (26), Oxford NOTECHS (30), and Oxford NOTECHS-II (33) are listed in this group. Only has the Oxford NOTECHS-II been psychometrically assessed in a population of orthopedics in an Asian country (40). Like other tools introduced in the above, due to differences in duties and job descriptions of surgical team members, these skills may be different in various countries.

5. Conclusions

According to the present findings, the empowerment of each member of the operating room department in utilizing the required NTS is imperative. Attention to these skills has resulted in the development of several tools over the last two decades in different countries. Since the development of tools and the identification of these skills depend entirely on the context and job description of the operating room team members, all countries must customize the available tools and develop similar tools for other members of their surgical teams, including the circular nurses, surgical assistants, and surgical technologists. Undoubtedly, improving NTS alongside technical skills can only be realized when the curriculum development authorities for these disciplines prioritize the training and assessment of these skills in their educational agenda.