Since 20 February, when the first cases of COVID-19 were detected in Iran, the Iranian health sector has borne heavy burdens, with 182,545 positive cases and 8,659 deaths as of 12 June 2020 (1). Due to explosive spreading of COVID-19, Iran experienced one of the highest burdens of the COVID-19 pandemic in the early days (2, 3), in such a way that the intensive care units (ICUs) were almost full. In response, the Ministry of Health designated a number of hospitals for coronavirus patients and suspected patients in different cities, meanwhile trying to encourage mild and moderate patients to home quarantine themselves (4). Furthermore, extensive training programs developed to inform the public about effective ways to prevent disease and transmission of the virus (5).

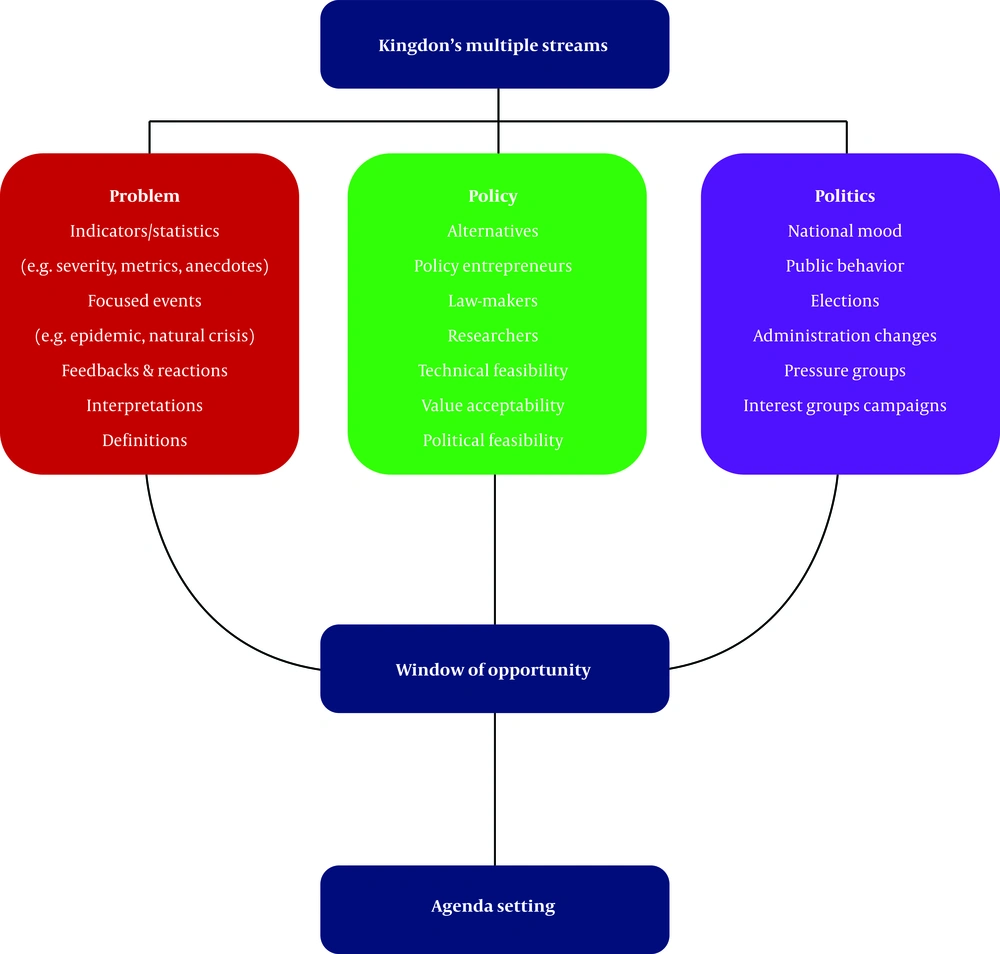

Despite these measures, the incidence rate of COVID-19 in Iran is still significant, which has created various challenges for the whole country as well as the health sector, like other nations. Based on the available evidence, the response of countries to this pandemic has been strongly influenced not only by the structure and organization of the health sector but also by the position of public health and primary health care in their health system (6, 7). For instance, although Veneto and Lombardia are two quite neighboring regions in northern Italy, their performance was meaningfully different in responding to COVID-19 (8, 9). In fact, Veneto’s better performance comes from policies such as: early active screening, proactive tracing of potential positive cases, and home diagnosis and care. Conducting effective and community-based health reforms is a crucial step in proper reaction to outbreaks, such as COVID-19 (8). Recognizing the current window of opportunity to fundamentally reform the health system in the light of analyzing the successes and challenges in the management of the current pandemic of COVID-19 through wise consideration of Kingdon’s multiple streams framework (Figure 1) could be of utmost importance for an adaptive and effective reform in a health system (10).

Although a series of measures have been taken to curb and control the spread of COVID-19, a number of problems have slowed down the fight against the disease globally and in Iran including (1) lack of proper tracking and tracing of potential patients; (2) Late stoppage of international and domestic travels; (3) weakness in diagnosing and defining the disease; (4) continuing gatherings; (5) insufficient public transportation and overcrowding; (6) crowded medical centers with many interactions; (7) existence of crowded residential complexes; (8) inappropriate reductionism of the current pandemic; (9) weakness in collaboration and teamwork; (10) delay in applying predictive models to facilitate forecasting; and (11) lack of comprehensive policies to attract public support (4).

However, combating against this pandemic has been marked by significant successes , which in the case of Iran include: (1) partnership of elites and religious leaders with the health system and their advocacy of health sector decisions; (2) using the Primary Health Care (PHC) network to track and identify suspicious cases as well as facilitating the home-based quarantine of positive cases; (3) rapid expansion and strengthening of laboratory networks throughout the country; (4) use of information technology infrastructure for registration and tracking; (5) success in reducing travel and interactions during holidays; (6) success in involving non-governmental organizations and science-based companies in supplying needed devices and personal protective equipment; (7) success in implementing preventive measures and social distancing policies in some difficult environments such as prisons and temporary discharge of low risk incarcerated persons; (8) using virtual education and keeping pupils and students away from public environments; and (9) increasing the public awareness about the disease and also the effective ways to prevent transmission (5, 11, 12).

Despite all challenges posed to the health sector, the COVID-19 pandemic has prepared a favorable opportunity for comprehensive and evidence-based reforms in health systems worldwide and in Iran. In accordance with the Kingdon’s multiple streams, when three streams or events (problem, policy, and politics) collide, the window of opportunity will be open for policy entrepreneurs to develop and propagate their issues in agenda-setting processes (13). The current COVID-19 pandemic is currently one of the main concerns of the public, politicians, and experts. Thus, COVID-19 has become very important socially, and there is public expectation from the government and the governing structures to take action. This is a window of opportunity to take advantage of the focus on health by all, to launch a profound reform in the health sector.

Although the importance of PHC and a referral system are well-recognized axes of such a reform (14), this process will not be easy. There is a range of issues which may affect the reform planning and implementation especially in Iran including idealism without effective change program, heterogeneity in the different parts of the country with regards to culture and economic and social aspects, conflict of interests among the decision-makers, failure of the urban Family Physician Plan (FPP) in the current form in Iran, immigration to big cities and increasing marginalization and indwellers of the suburbs and ignoring cost-effective interventions.

Furthermore, given recent events such as the starting of a new parliament, greater public confidence in the health care system, solidarity among the public and authorities following the COVID-19 outbreak, as well as economic issues following international sanctions and declining oil revenues, the experience of change and conducting health reform programs in Iran especially in establishing the PHC during the imposed war against Iran some 34 years ago (15), the existence of information technology infrastructure, Iranian Health Insurance Organization (IHIO) and other insurance companies, can be potential factors that provide a good platform for developing and implementing effective reforms.

In general, due to the intersection of the three streams (problem, politics, and policy) and preparing opportunities for health policy entrepreneurs for reform in the Iranian health system, these suggestions could be made (1) moving towards a holistic medical education; (2) promoting the strategic values of integrating medical education into the health care system; (3) developing a system for continuous monitoring of diseases and potential hazards; (4) determining the health needs of different population groups; (5) rationing and prioritizing the interventions based on available resources, disease burden, fairness, acceptability, etc.; (6) integrating the adopted policies; (7) developing a clear executive mechanism for policies and also determining transparent outcomes for them; (8) considering the process model of providing health services as a basis for designing the health care structure; (9) strengthening the referral system and FPP; (10) prioritizing the public health.

In addition to the above recommendations, given the importance of the PHC network in the fight against diseases, especially epidemics and pandemics, improving this network should be the main priority of the Iranian health system as well as other nations in the coming years. A number of policy solutions could improve this network including (1) redesigning the PHC network integrating health, treatment and medical education; (2) moving towards financial independence and accountability of the PHC network; (3) increasing public participation and better communication with local councils and authorities; (4) empowering health care providers and health workers (Behvarz); (5) promoting team working; (6) establishing the FPP with the support of general practitioners; (7) using appropriate payment mechanisms such as capitation and pay-for-performance; (8) designing the health benefits package with a focus on preventive and basic health services; (9) diminishing the out-of-pocket payments using a comprehensive referral system, and (10) continuous monitoring of the PHC network performance and short-term and long-term consequences of measures.

To manage these activities, the headquarters of the ministry of health needs reform in structure and function. In this regard, these issues should be considered: (1) strengthening the planning dimensions and function and strategic supervision process; (2) moving towards agility and innovation; (3) using specialized workforces; (4) reducing executive duties and promoting governance duties; (5) improving communication with the public and developing advocacy plans; (6) effective management of inter-sectoral collaborations; (7) using the principles of operational budgeting, and (8) setting clear goals in order to hold the authorities accountable.

In conclusion, the current window of opportunity for health sector reform is a unique occasion that could lead to a healthier world for all and more rapid access to universal health coverage. The current solidarity by all toward the health system should be valued and approached appropriately.