1. Background

According to the official reports, the world population was around 7.63 billion people in 2018, and it is still growing in number (1). Iran is no exception to this rule. According to the latest report of the Statistical Center of Iran, around 7,300,000 Iranians are of old age, which makes up 9.3% of the national population (2). As the aging population grows, the health-related issues of older people become more prominent and urgent. Falls have been one of the most common of such problems that, depending on the severity of the injury, usually need medical attention (3).

Falls are considered the second biggest cause of death by injury (accidental or unintentional) around the world. An estimated number of 646,000 deaths caused by falls are reported each year worldwide, of which a large majority (almost 80%) occurs in countries with low or middle income (4). In a six-month cohort study in Iran, 7.8% of elderly people aged 60 years and above reported a history of falls, almost half of them experienced falls once, a quarter had them twice, and the rest had three or more incidents (5). Of all the people who experience falls, 20% to 30% are injured moderately to severely and suffer fractures, lacerations, or even traumatic brain injuries (4).

Fall is also the cause of 10% - 15% of emergency department referrals and 50% of hospitalizations due to injuries among people 65 years and older (6). The fall is the result of the interference of several factors. Internal factors (such as age-related changes, chronic conditions, gait and balance function, visual and auditory impairments) and environmental hazards (insufficient lighting, lack of railings, inadequate surface, use of walking aids, and type of housing) can lead to falls in the elderly (7).

Since falls can result in more adverse and complex medical conditions in older people, finding more effective preventive intervention methods that can positively modify fall risk factors is of utmost importance (8). However, there have been few studies to examine the fall prevention intervention programs targeting the risk factors in this age group (9). Findings of more recent systematic reviews demonstrate little evidence for multifactorial intervention methods designed to prevent falls among older people who reside in community-like establishments (10, 11).

Since the factors affecting falls are multifactorial, the application of one intervention alone cannot prevent falls in the elderly. In a trial that was published in 2004, a multidimensional fall prevention program called Stepping-On was experimented on a group of old people residing in a community. The results showed that the experimental group had 31% fewer fall incidents compared to the control group (12). Stepping-On was developed in Australia (13). The program has already been successfully introduced in the United States.

The services offered by the Stepping-On program to the elderly include providing information, showing strategies to reduce the risk of falling, and teaching techniques to be more confident when there is a high risk of falling (14).

2. Objectives

This program is based on adult learning principles and the assumption that older people are capable of learning and changing behavior. Given that to the best of the author’s knowledge, few studies have been conducted regarding this program, and considering the importance of falling incidents in the elderly, the author decided to conduct a study to determine the effectiveness of the Stepping-On fall prevention program on the quality of life, fear of fall, and fall-preventive behaviors among community-dwelling older adults in Shiraz, Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Samples

The present research is a two-group clinical trial with a pretest-posttest and one-month follow-up design. One hundred elderly people consulting two of the largest health centers affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Shahid Motahari and Imam Reza Multi-Specialty Clinics) participated in this study. The study was conducted over the course of May 2019 to Aguste 20 20, in Shiraz, Iran. The current research was registered in the Iranian clinical trials registry (code: IRCT20190506043498N1).

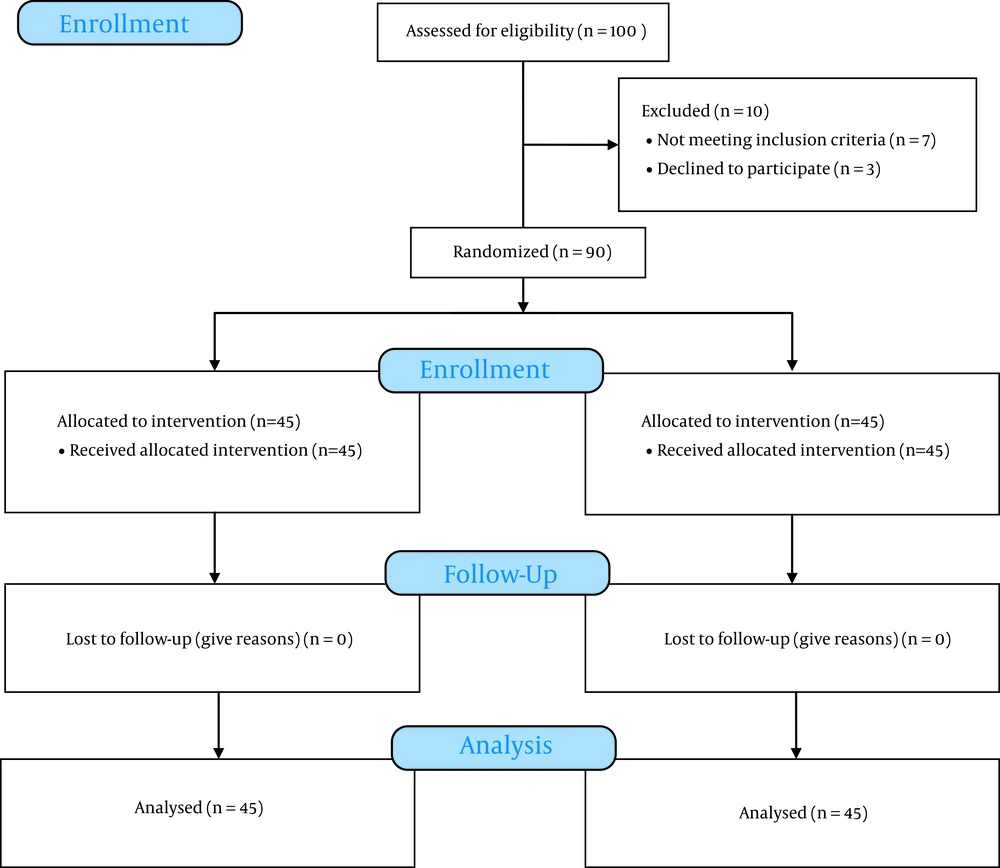

Considering α = 0.05, a power of 90%, and an effect size (the intensity of the association between two variables) of 0.7 according to data provided by Abbasi et al. (15) and Ghezeljeh et al. (16), the sample size was determined to be 86 people, which was rounded up to 100 to take a 16% drop rate into account (50 people were allocated to the control group and 50 were allocated to the intervention group). Samples were chosen in stages. In the first, we identified two health centers (Shahid Motahari and Imam Reza Clinic) through a simple random sampling procedure. Afterward, 100 elderly people who were referred to the elderly clinic and family physician (FP) of these clinics for routine follow-up were enrolled in the study. However, seven subjects did not meet the inclusion criteria, and three-person refused to take part in the study. Finally, 90 subjects, who were recruited to the study using the convenience sampling method, were randomly divided into the intervention (n = 45) and control (n = 45) groups. Assigning individuals to the groups was carried out through block randomization method with Block size 4. With two groups of control (C) and intervention (T), six possible equilibrium combinations were calculated (TTCC, TCTC, TCCT, CTTC, CTCT, CCTT), and blocks were randomly selected to determine the allocation of all 90 individuals to the groups. This process was repeated until all the samples were included, and the sampling sequence was recorded in sample table. According to this table, all of the participants were divided into the groups. It should be noted that during the training sessions and follow-up time, none of the participants were excluded from the study (Figure 1). The participants were unaware of the randomization process and the group they belonged to during the study, making the study single-blinded. The inclusion criteria were being at least 60 years old, a history of falling, willingness to participate, and awareness of the time, place, and person. Exclusion criteria were a history of participation in similar studies, absence over two sessions or death, and incomplete answers to the questionnaire.

3.2. Data Collection and Intervention

Data collection tools included a demographic questionnaire, the Falls Efficacy Scale International, the Fall Behavioral Scale, and Lipad quality of life questionnaires. The demographic questionnaire included gender, age, and education level, drug abuse, fear of fall, and underline diseases.

The Falls Efficacy Scale International questionnaire, developed by Yardeli et al. in 2005 (17), was used to examine the elderly’s fall-related self-efficacy (fear of falling). This tool consists of 16 items, each measuring the level of the elderly’s fear of falling in a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (no fear) to 4 (extreme fear). The scores range from 16 to 64 points. Higher scores demonstrate a decrease in fall-related self-efficacy and greater concerns about a fall. The studies previously conducted in Iran have reported a 98% reliability level for the Persian questionnaires using Cronbach’s alpha (18).

Lipad fall-related quality of life questionnaire consists of 31 questions and assesses the elderly’s quality of life in seven dimensions of physical function (five questions), self-care (six questions), anxiety and depression (four questions), mental function (four questions), social function (three questions), sexual function (two questions), and life satisfaction (six questions). The scoring of this questionnaire is similar to the Likert Scale, each question offering four options to check with scores ranging from zero (the worst condition) to three (the best condition) (19). The validity and reliability of the Persian version of the Lipad fall-related quality of life questionnaire have been confirmed in the study of Ghasemi et al. (20) and its reliability coefficient using Cronbach’s alpha was reported to be 0.831.

Fall Behavioral Scale was developed in 2003 by Clemson et al. (21) to determine the presence or absence of protective behaviors that older people perform to prevent falls. It is a valid and reliable tool with the internal consistency of 0.84 and test-retest reliability of 0.94, and content validity of 0.93 (21). The scale consisted of 30 items. The six-item scores (questions 7, 8, 9, 10, 19, and 23) are computed in reverse order. Lower scores reflect risky behaviors, and higher scores mean that the person is safer and has more fall avoidance behaviors.

To utilize FBS scale in Iranian culture, the scale was translated into Persian and retranslated by experts to be applied in the present study. Face validity of the scale was determined by quantitative and qualitative methods using content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) by 10 professors in the field of instrumentation, geriatrics, and psychiatric nursing of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences as a panel of experts. To identify the qualitative validity of the scale, experts were asked to provide the necessary feedback after a qualitative review of the scale in terms of grammar, use of appropriate words, necessity, importance, and appropriate scoring, simplicity, clarity, and the level of difficulty. Corrections were made accordingly in the scale, and items with CVRs greater than 0.62 (minimum value of CVR in the Lawshe table for 10 specialists) (22) were preserved. To determine the content validity index (CVI), panel of experts were asked to determine the relevance of each item of the questionnaire based on a 4-part Likert Scale (from irrelevant to completely relevant). Thus, items with a CVI score higher than 0.8 were retained. Accordingly, no item was deleted from the scale. After that, the questionnaire was distributed and completed among small samples (30 people) of the elderly, and its possible corrections were considered (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.90).

The intervention was performed in the form of Stepping-On fall prevention program, which is an evidence-based training course. The Stepping-On program consisted of seven 30-60-minute training sessions being held for the intervention groups two days a week in the selected healthcare centers. Table 1 indicates the contents of the program throughout the seven sessions. During the sessions, teaching aid tools such as slide presentations, video projectors, and educational images, and videos were used. Meanwhile, the control group received no such intervention. However, the control group was provided with Stepping-On program educative materials in the form of DVDs at the end of the study. Additionally, the control group received a booklet written based on credible scientific sources.

| Sessions | Contents |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction, a review of the stepping on intervention program, review of the participants’ fall experiences, exercising strength and balance exercise |

| 2 | Review of the previous contents, expressing the benefits and barriers of exercising, how to walk, and how to secure chairs and staircases |

| 3 | Home hazards and modification and secure the elderly living environment |

| 4 | Providing the community with strategies for safe walking, introducing the properties of safety footwear, elderly-friendly living area, and the appropriateness of footwear and clothes. The importance of activity and movement |

| 5 | Explanations regarding vision, falling, and the importance of consuming vitamin D |

| 6 | Explanation regarding medication management, practicing the techniques taught in a nearby space |

| 7 | Review of the previous contents and explaining future plans, answering the questions |

Stepping-On Fall Prevention Program

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences with a code of IR.SUMS.REC.1398.83. All participants signed an informed consent form. They were educated that their cooperation was optional and they would be free to withdraw from the study at any time. In addition, all data collected from them remained confidential.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS V.22 using independent and pairwise t-tests, chi-square (χ2) test, and repeated measures analysis of variance at a significance level of P ≤ 0.05.

4. Results

The results indicated that a majority of those who participated in this study were females. The average age of the participants was 69.2 ± 5.38 in the control group and 67.3 ± 4.09 in the intervention groups. Based on the results, no significant difference was observed between the intervention and control groups in terms of demographic variables (p > 0.05), and the two groups were similar in this regard (Table 2).

| Variables | Groups | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||

| Gender | 0.844 | ||

| Female | 24 (53.3) | 23 (51.1) | |

| Male | 21 (46.7) | 22 (48.9) | |

| Married status | 0.142 | ||

| Single | 10 (22.2) | 17 (37.8) | |

| Married | 35 (77.8) | 28 (62.2) | |

| Level of education | 0.473 | ||

| Illiterate | 7 (15.6) | 13 (28.9) | |

| Primary | 15 (33.3) | 12 (26.7) | |

| Diploma | 13 (28.9) | 11 (24.4) | |

| University | 10 (22.2) | 9 (20) | |

| Drug abuse | 0.210 | ||

| Yes | 5 (11.1) | 9 (20) | |

| No | 40 (88.9) | 36 (80) | |

| Fear of fall | 0.653 | ||

| Never | 14 (31.2) | 10 (22.2) | |

| Rarely | 15 (33.3) | 20 (44.5) | |

| Sometimes | 10 (22.2) | 9 (20) | |

| Most times | 6 (13.3) | 6 (13.3) | |

| Underlying diseases | 0.065 | ||

| Yes | 14 (32.6) | 8 (15.9) | |

| No | 31 (67.4) | 37 (84.1) | |

Comparison of the Demographic Characteristics of the Research Samples in the Two Groups of Intervention and Controla

As Table 3 shows, there was no significant difference in fear of falling scores between the two groups prior to study conduction (P = 0.059). The difference remained insignificant after the study was carried out. However, a significantly different fear of falling was observed between the two groups two months after the intervention (P = 0.02). The repeated measure ANOVA revealed a significant difference in the participants’ fear of falling while the study was being conducted (P = 0.008), indicating that the intervention was effective in reducing the elderly’s fear of falling.

| Variables | Before the Intervention | Immediately After the Intervention | Two Months Later | F, P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Group | Time/Group | ||||

| Fear of fall | F = 2.94; P = 0.067 | F = 7.26; P = 0.008 | F = 0.180; P = 0.789 | |||

| Intervention | 33.1 ± 9.6 | 32.1 ± 11.3 | 29.9 ± 9.3 | |||

| Control | 37.5 ± 11.9 | 35.5 ± 5.7 | 34.8 ± 10.6 | |||

| P-value (t-test) | 0.059 | 0.069 | 0.022 | |||

| Fall preventive behavior | F = 4.83; P = 0.01 | F = 3.79; P = 0.055 | F = 1.89; P = 0.157 | |||

| Intervention | 67.9 ± 12.4 | 74.5 ± 10.5 | 75.1 ± 13.1 | |||

| Control | 67.5 ± 13.7 | 68.3 ± 18.1 | 69.9 ± 9.38 | |||

| P-value (t-test) | 0.894 | 0.046 | 0.028 | |||

| Quality of life | F = 1.22; P = 0.296 | F = 5.66; P = 0.019 | F = 2.58; P = 0.081 | |||

| Intervention | 63.7 ± 10.9 | 66.7 ± 12.6 | 69.5 ± 12.2 | |||

| Control | 63.1 ± 9.8 | 62.7 ± 10.8 | 62.1 ± 12.5 | |||

| P-value (t-test) | 0.815 | 0.114 | 0.005 | |||

Comparison of the Mean of the Fear of Falls, the Fall Behavioral and Quality of Life Between the Two Groups Studied Before, Immediately, and Within Two Monthsa

Although, there was no significant difference in the score of fear of fall across the three time periods (P = 0.067).

Time was not a significant factor in reducing the participant’s fear of fall.

In terms of fall preventive behaviors, as Table 3 indicates, no significant difference was found between the intervention and control groups before the study (P = 0.894). However, a significant difference between the two groups was observed immediately after the interventions (P = 0.046) and two months later (P = 0.028). Repeated measure ANOVA indicated that time had a significant impact on the fall preventive behaviors (P = 0.01); however, interaction between the time and the groups was not significant (P = 0.157).

Additionally, according to the independent t-test, no significant difference was observed between the two groups’ average quality of life before the intervention, and the intervention and control groups were homogeneous in this regard. There was also no significant difference between the two groups’ average quality of life immediately after the intervention (P = 0.114). However, a significant difference in terms of the average quality of life was observed between the two groups at the follow-up (P = 0.005). In addition, the repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated that the groups were significantly different in their average quality of life score during the study (P = 0.019); however, the impact of time (P = 0.296) and the interaction of time and the group was not significant (P = 0.081), revealing that time was not a significant factor contributing to this variable.

5. Discussion

The results of the present study indicated that the stepping-On fall prevention program has an impact on decreasing the fear of falling. Tennstedt et al. (23) indicated that group intervention is effective in reducing the elderly’s fear of falling as well as physical activity limitations attributed to it. The study of Brouwer et al. (24) indicated that training programs reduced the average fear of falling score. Najafi et al. (25) suggested that providing the elderly who reside in Mashhad nursing homes with educational content via video was effective in reducing their fear of falling. The results of the aforementioned studies indicate the positive impact of educational interventions using various educational methods on the elderly’s fear of falling, one of the reasons for which might be the fact that these educational programs regarding the correction of falling risk factors can be implemented at home. A systematic review also showed the effectiveness of multidimensional interventions, especially in reducing the fear of falling of the elderly living in the community (26).

Teaching balance and strength exercises to improve the elderly’s muscular function was among the other methods used in the present research, whose results are consistent with other similar pieces of research. The results of a 2015 systematic review study titled “the impact of exercise programs on the reduction of falling in elderly people suffering from dementia” conducted by Burton et al. (27) indicated that exercise interventions result in reduced fall incidents in the elderly. The Stepping-On program is an evidence-based program improving Fall Behavior Scale through training and emphasizing the main fall risk factors. This program reduced the research population’s fear of falling through training, balance and resistance exercises, medication management, adjustment with vision impairments, and improvement of household environment and safety across the research population. One study reported a 31% fear of falling reduction thanks to this program (13). The program is suggested as an effective measure in preventing falls in the United States (14).

The results of the present study indicated that the Stepping-On preventive program resulted in the improvement of fall preventive behavior in elderly people. Falling risk factors such as medication interventions, calcium and vitamin D consumption, environmental risk factors, vision improvement and correction, footwear modification, and balance training were taught over the course of this program. Pit taught a group of elderly people to perform self-evaluation and balance their medication with the help of a pharmacologist and discovered that such training resulted in a significantly reduced risk of falling (28). Examining the impacts of vitamin D, Gallagher also reported a significant decrease in falling risks and rates (29). Environment adjustment training was used in another research conducted by Gillespie to prevent falling, which yielded results consistent with other studies. According to the latest meta-analysis regarding the adjustment of environmental risk factors conducted across six studies with a research population of 4,208 subjects, the rate of falling decreased by 19% (30). MacK (31) investigated the impacts of installing an anti-skid part on winter footwear and observed a significant reduction in falling rates.

The results of the present study indicated that prevention programs could result in an improved quality of life. Hamidizadeh et al. (32) reported that light exercise training for the elderly increased their quality of life. A number of fall-preventive measures were suggested by Karlsson et al. (33) among which household environment adjustment proved to improve the elderly’s quality of life significantly. Self-care programs, exercising, and taking physical tasks were reported to increase the quality of life in a study conducted by Dickson et al. (34). Barrett and Smerdely’s results (35) also confirmed that training increases the elderly’s quality of life. According to the results of the present study, it is suggested to consider the stepping on program as a part of the elderly’s treatment programs to prevent several physical, emotional, and social complications that involve the elderly and reduce their quality of life. Similar to other studies, this study has some limitations of which the most important one is that it only concerned the elderly referred to selected healthcare centers in Shiraz and did not cover a wide range of elderly people; therefore, a wider statistical population is required so that the results can be generalizable.

5.1. Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that the Stepping-on program reduces the fear of falling as well as the rates of falling, improves Fall Behavioral Scale, and results in an improved quality of life. According to the results of this study, it can be said that improving the participants’ knowledge of risky behaviors and preventing them are essential factors for reducing the rates of falling in the elderly.