1. Context

Corruption is an intricate concern in health systems all over the world, however, with different levels of intensity. Factors such as providing the majority of health services by the governments and its resulted monopolies, lack of transparency on the financing process, and low accountability, along with limited citizens' voice have made low and middle-income countries (LMICs) more prone to corruption compared to developed countries (1). One of the most comprehensive and brief definitions of corruption is "the abuse of entrusted power for private gain" (2). In a global health context, this concept is defined as "misappropriation of authority, resources, and trust or power for private or institutional gain that has adverse effects on regional, local or international health systems that may negatively affect an individual patient and/or population health outcomes" (2). Noticeably, three characteristics of the health system, including information asymmetry, uncertainty, and a large number of actors, make it more susceptible to corruption (3).

Studies show that corruption of the health system results in not only losing around $455 billion annually worldwide but also has led to reducing global citizens' trust in the health system. Sadly, 1.6 percent of global under-five mortality (140,000 deaths) is connected to corruption (4). Furthermore, corruption reduces the availability and quality of healthcare services, increases the cost of care, and ultimately leads to inequity in the utilization of services. It has also a destructive effect on the population's health status by discouraging them to use and pay for their required services. Finally, according to evidence, an increase in corruption makes a reversely substantial impact on life expectancy (5). Health system corruption is a severe obstacle in the way of universal health coverage (UHC) and sustainable development goals (SDG) (2).

Based on the definition of Good Governance, it maximizes the capacity of states to develop and implement health policies for the public's benefit, to manage related resources prudently, and to provide health services efficiently and effectively, while corrupt governance fails to offer citizens adequate and accurate information about government and its policies. Thus, corruption weakens the amount of responsibility and accountability of government officials, reduces transparency in the field of state institutions, and it can lead to systematic violation of human rights (6). Good health governance with its all dimensions, such as accountability, transparency, responsiveness, and citizens' participation, will be the best strategy to combat corruption in health systems (7).

According to corruption perceptions index (CPI) 2018, Iran ranked 148 among 183 countries (8). This situation shows the crucial importance of considering corruption and its negative effects on Iran’s development. It also can be the hallmark for the extent of corruption in Iran's subsystems, including the health system. There is less documented evidence about corruption in Iran's health system, and most available evidence has argued about the general framework for corruption assessment or providers' related corruption (9, 10). Recently, the Minister for Health (Dr. Namaki) has bolded corruption in the health system and emphasized the requisiteness of paying serious attention to this harmful issue (11). In response, in this review, we aimed to shed the light on corrupt practices in Iran’s health care system and recommend some practical strategies to combat them.

2. Evidence Acquisition

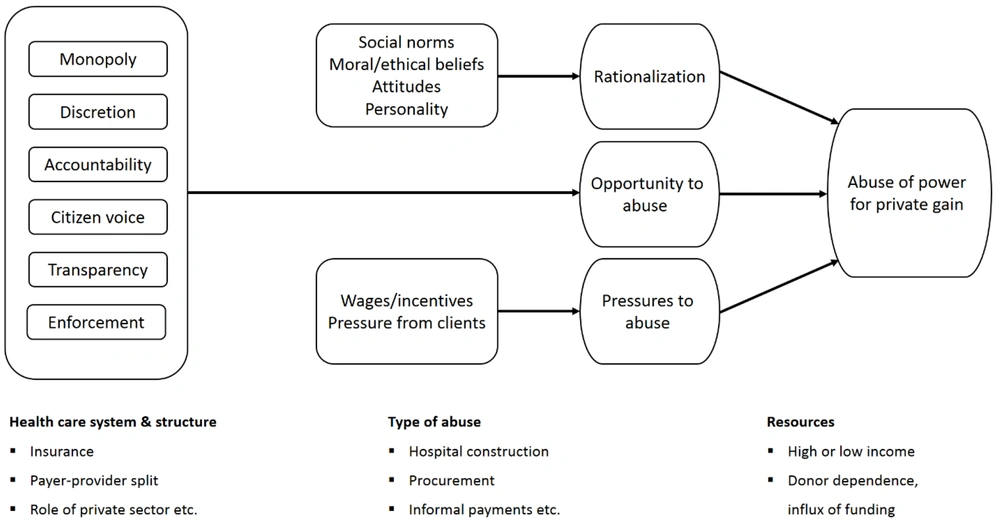

This is a narrative review (12, 13) based on Vian's conceptual model of corruption in the health sector (Figure 1) to evaluate and analyze corruption in Iran's health system (14). This model considers six areas of monopoly, discretion, accountability, citizens' voice, transparency, detection, and enforcement. Indeed, since this model considers the proximate causes and also driving (enabling) factors that facilitate or hinder corrupt activities in the health care systems, provides a favorable framework to evaluate the potential corruptions (15). Specifically, proximate causes refer to situations such as inappropriate control systems and excess discretion that provide opportunities for abuse of power. Furthermore, the presence of motivators and pressures along with rationalizations are other proximate causes that can facilitate and justify the occurrence of abuse. Driving factors point to conditions such as monopoly, lack of transparency and accountability, and inadequate audit and enforcement mechanisms that lead to individual and organizational corruption.

Review of the literature and documents without any time limitation was conducted from September 2018 to February 2020 in several databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and official website of World Health Organization (WHO) and other relevant international agencies. To find domestic evidence, we extended our search to Persian sources, including Iran Medex, scientific information database (SID), Magiran, and the official websites of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) and formal news agencies. All original articles, reviews, and official reports are included in our searches, letters, correspondence, proceeding abstracts, and unofficial reports were excluded.

Free-text words, medical subject headings (MeSH), and the Emtree thesaurus were applied to recruit the relevant terms. Considering the above-mentioned typology and with focus on the outcome of each area, keywords of "Iran" and "Health sector" or "Health system", and "corruption" and "ethics", "rule or regulation", "Law", "informal payment", "conflict of interest", "pharmaceutical industry" or "drug supply", "medical instruments industry", "public sector", "private sector", "monopoly", "discretion", "accountability", "transparency", "responsiveness" were considered. To access the existing solutions and recommendations to reduce corruption, keywords of "Low- and Middle-income countries" AND "corruption", and "good governance" were searched as well. To have a comprehensive approach the subject has been sighted from three aspects, including public health law, ethics and human right, and health policy.

Based on the abovementioned search strategy and inclusion and exclusion criteria, 28 out of 51 articles are included in our review. All included articles reviewed by HJ, AK, SSH, and FA, and based on the keywords and the area of expertise of each researcher the results were retrieved. Any disagreement during the selection process was resolved using discussion and consultation.

3. Results

In this review, corruption in Iran's health system and its predisposing factors have been studied. To the best of our review, there is less published evidence about the extent and types of corruption in Iran's health system. However, due to the importance of this issue, we conducted our analysis based on the available documents and using Vian's Conceptual Model of Corruption in the Health Sector (2008). As the model illustrates, monopoly, discretion, accountability, citizen voice, transparency, and enforcement are six structural enablers through which a health system will be prone to corruption.

3.1. Monopoly and Discretion

Evidently, Iran's health system is essentially monopolistic and self-authorized, and the Ministry of Health, in many cases, simultaneously is the provider, supervisor, and purchaser of the healthcare services (16, 17). A significant portion of the healthcare services, especially at first and third levels, are being provided by public sector; however, in the second level majority of services are delivered by the private sector (18). Moreover, all basic health insurance companies are public, and the government has a dominant role in health sector financing. Noticeably, social security insurance organization has its own facilities to deliver health services to the under-covered population. Accreditation of the public sectors and private sector is also being done by the Ministry of Health. The above-mentioned fact reveals no split between purchasers and providers in this health system (19). Likewise, almost all pharmaceutical companies were nationalized by the government after the Islamic revolution (20). Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of Iran buy, stock, distribute and supervise the cycle of drug provision in all public sectors. It also supervises and manages the drug provision cycle in the private sector, while most of the managers in this organization have their own pharmacy or some of them are a shareholder of pharmaceutical companies (21). Furthermore, the construction of health centers, hospitals, and other public health authorities is managed, licensing and contracted by the ministry of health and its affiliated organizations. In a mix method study implemented in Iran, participants included health sectors' construction at risk of corruption (22).

3.2. Transparency and Accountability

Based on published evidence both transparency of decision and accountability of decision-makers are low in Iran’s health system (23, 24). Unfortunately, the chaotic health system of Iran without strong stewardship and fragmentation in the financing system is a predisposing factor to reduce its accountability and prone to corrupt activities (25). Moreover, there is less transparency in data management and health information system (26). This issue has led to shortage of reliable data and statistics for policy-making in health insurance system and ultimately could contribute to fragmentation in health insurance funds (27). In addition, inappropriate applying laissez-faire by the economic policymakers has resulted in government share reduction in health financing without improving the utilization of the private sector’s power in the health services provision (28). Poor health governance in Iran's health system is the other factor related to corruption, which is mentioned in another study. According to this study and regarding requirements of good health governance including, accountability and responsiveness, the transparent policymaking process, citizen involvement, and operational capacity to design, manage, and regulate policies and provide services, Iran has many shortcomings in all of these desires (7).

3.3. Enforcement and Citizen Voice

One of the most important indicators for fraud in health system is dual practice, which is very common among physician specialists, especially in geographic full-time specialists (29, 30). Likewise, studies showed lack of enough law enforcement to data registry and reporting timely and accurately in whole parts of the health system, especially surveillance system of diseases (31, 32). As such, due to many dysfunctions in pharmaceutical systems, such as unregulated medicinal herbs’ market, unethical competition between distribution companies, and inappropriate structure of the current supply chain, law enforcement is highly recommended (33). In relation to citizen voice, there is no published evidence to mention.

4. Discussion

Generally, corruption is manifested by weak governance, low accountabilities, and no citizen involvement in the decision-making cycle (1). Furthermore, corruption practices are happening covertly and are related to “individuals' and institutional factors” and “social and cultural norms” (34). Although there are few published documents, the news and the authorities' statements show the worrying situation of the corruption in Iran's health system. In this study, we are discussing this issue in two parts; the first is the legal, ethical, and health system's consequences of corruption, and the second is the best possible customized strategies to deal with this issue in Iran's context.

4.1. Legal, Ethical, and Health System's Consequences of Corruption

Based on CPI 2018, Iran ranked 148 among 183 countries which is an alarming corruption indicator for both the whole system and its sub-systems (8). Corruption has many adverse effects on the healthcare system, including reducing quality and equity of care, increasing out of pocket payment for health expenditure via informal payment (30), mismanagement of resources and fraud, and reduced trust, thereby it would be the main barrier to attain UHC (4, 35). Similar to many developing countries, a majority of health services in Iran are provided by government monopolies where discretion and accountability are more likely to be abused. Furthermore, dual practice is a predisposing factor for absenteeism which, in turn, is an indicator of corruption. About 47.7% of surgeons working in whether public or private hospitals are involved in dual practice (36). Besides, informal payment as a type of fraud has a direct association with out of pocket payment (OOP) which means in countries with high OOP, informal payment is also high (4). Unfortunately, informal payments are a remarkable source of healthcare financing in developing countries such as Iran (37). The socioeconomic status of patients and providers in Iran has a significant impact on these unethical behaviors (37). Although there are controversies about the rate of informal payment, some studies showed that after the health transformation plan, it has changed to lower in the public sector (38).

4.2. Anti-corruption Strategies

Fighting corruption in the health system is not easy, but not taking action will not improve health. Therefore, the development of anti-corruption strategies is vital to promote health status. We strived to propose anti-corruption strategies using international experiences for the current conditions of Iran from two approaches, including health policy and ethics, and legal view.

4.2.1. Health Policy and Ethics

Some experts believe that the main goal should be to reduce the corruption that has the greatest impact on health outcomes and not all types of corruption. This statement can be logical, especially in undeveloped and developing nations like Iran. However, considering such actions require an understanding of the health system and the political context that governs it. Some anti-corruption measures are also specific to the health system itself, which are usually divided into four categories: (1) Strengthening top-down control; (2) strengthening bottom-up accountability; (3) strengthening ethics and motivation levels; and (4) anti-corruption approaches against donor programs (39).

According to what was mentioned, weakness in control and supervision processes is one of the main stems of corrupt activities in the health system. Thus, upgrade the control and monitoring system should be one of the priorities in anti-corruption strategies. For instance, in Brazil, enhancing the audit mechanisms reduced the corrupt activities in the procurement process significantly (40). Moreover, increasing community participation as an approach to enhance local accountability is rapidly expanding. This approach is very efficient and attractive in areas where there is a little political will to tackle corrupt activities or the current capacity to establish effective central oversight is not enough. For example, providing the price of healthcare services publicly led to a decrease in a wide range of corrupt activities in Nigeria (41). Indeed, the majority of corruption at the service provision level comes from the lack of awareness of recipients. Therefore, moving on to providing enough information about the type of services covered by health insurers, the number of direct payments, etc. can prevent corruption (individual accountability). On the other hand, patients have not sufficient power and organization to control providers. In such conditions, structured groups are involved in the local levels and hold the providers accountable for their performance and consequences (community accountability). Findings from a recent study in Uganda revealed that community involvement in the monitoring process can have appropriate effects on reducing corruption and improve health outcomes (42). According to the geographical distribution and weakness of the information systems in Iran, considering such strategies can curtail the space for potential corruption.

It is noticeable that "the level of social capital"(43, 44), " the state of economic growth and the level of gross domestic product (GDP)"(45, 46), "the level of inflation"(46, 47), "the comprehensive economic sanctions"(48), "the rate of Organizational and Policy Ethics Literacy"(49, 50) and “the oil-dependent economy”(51) make Iran's health system so vulnerable to corruption.

4.2.2. Legal Solutions

Generally, good governance and successful implementation in the health care system are important issues. It is important to implement accountability measures as a central concept for good governance (7). Accountability requires that elected and unelected officials in the government account for their performance to the public or their duly elected representatives (52). Once these accountability measures are implemented, public officials will be under the scrutiny of the populace and will be less likely to engage in corruptible acts. Studies show that good governance in Iran’s health system is in disorder (good governance in health system) (53).

Anti-corruption efforts centered on institutional reforms are premised on a legal approach, which combines reforms in the legal spheres (such as enforceable property and contract rights and measures to enhance the credibility of the judiciary), innovations in the governance sphere (strengthening mechanisms of accountability, controls over discretion and resource use and improvements in terms and conditions of employment for civil servants) and specific institutional mechanisms (such as creating an anti-corruption agency, special courts to review corruption cases, and asset declaration for politicians and civil servants) (54).

Based on the analysis and evaluation of the studies (55), amendment of the upstream documents is recommended to clearly state the position as to the competence to legislate on corruption as between and among the tiers of government. There is no need for reform in our legal system. What we need is constant and close surveillance, legal responsibility, and successfully implanted laws (56). For example, the effective exercise of the oversight functions of the legislature over the activities of the executive could be effective in fighting corruption in the Iranian Health Care System (10). Moreover, a specialized court system should be established for corruption cases and with specific judges (57). The Iranian government should make public expenditures more transparent, with clearer rules on procurement and budgeting. Anti-corruption agencies in Iran should be strengthened and linked with other international anti-corruption bodies like Transparency International (TI) to build capacities and monitor international collaborators toward a corruption-free society (58).

All processes of such a system need to be explicit and transparent, and anti-corruption laws and regulations need to be scrupulously enforced (55). One way to help measure the quality of public services is to publicize public perceptions of corruption, in particular government departments and medical institutions (59). Patients’ rights should be delineated, a system should make it easy to register and investigate complaints, and taking complaints through the courts should be simplified and made less costly.

This is one of the few studies implemented on corruption in Iran’s health system comprehensively. The most important limitation of this study is limited access to gray literature and official reports on corruption in Iran's health system, and the other one is a shortage of publication in this domain.

4.3. Conclusions

Based on this study, evidence shows corruption in financing, service provision, and resource generation of Iran's health system. It could affect not only the performance of this system but also its responsiveness and effectiveness. To combat, Iran should apply multiple strategies such as improving good governance, strengthening legal system over the health system, reducing monopoly and discretion stepwise and manageable, enhancing community participation, reconceptualizing ethics in a systemic approach, and updating ethics codes in health system. It is worth mentioning that the historical context of corruption in Iranian society and socio-cultural dimensions of the issue are crucial aspects to be investigated and studied in the future. Finally, methodological solutions and strategies with an interdisciplinary approach could be developed in future studies following this review.