1. Background

The HIV/AIDS remains an ongoing global health problem, particularly in the Middle East and low-income countries. In 2019, a total of 38.0 million people living with HIV (PLWH) were identified, and 1.7 million people were newly infected with HIV. Additionally, 97% of new HIV infections were reported in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). There are 240,000 PLWH and 20,000 newly detected HIV patients in MENA countries. According to reports by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) (2019), approximately 25% of PLWH (n = 59,000) and 20% of new HIV cases (n = 4,100) in MENA are reported in Iran (1-5).

The UNAIDS has set the 90-90-90 targets, according to which by 2020, 90% of PLWH would know their status, 90% of these individuals would be getting treatment, and 90% of individuals undergoing treatment would have suppressed viral loads (6, 7). The latest data from Iran (2019) shows that the aforementioned figures are 36%, 20%, and 17%, respectively (1, 8), suggesting that Iran is failing to terminate the spread of HIV and meet the aforementioned targets (7).

A thorough understanding of the local disease situation is paramount in order to meet the UNAIDS targets. The HIV status in Iran is unique due to problems, such as changes in the routes of transmission and challenges of treatment and care programs (9, 10). However, Iran and MENA countries share some common features, such as inefficient leadership of HIV/AIDS programs, social stigma, discrimination, an increase in the average age of marriage, the rates of premarital and/or extramarital sex, HIV-infected newborns, risky behaviors, and reluctance to address sensitive issues (3, 9, 11-15). Certain societal norms, such as strong belief in alternative or traditional medicine, might exacerbate the issue (16). Apart from these issues, there is always the possibility of sudden outbreaks; therefore, special attention should be paid to patients with HIV/AIDS (17).

Service quality and patient satisfaction play an essential role in the patient’s compliance with the treatment programs. Quality of services is a multidimensional phenomenon. Most studies have assessed the quality of these services from two perspectives, technical (i.e., scientific standards by health professionals) and functional (i.e., ways of delivering health services to clients). Considering the importance of service quality in tackling HIV/AIDS problems and achieving the specified targets, continuous monitoring and evaluation of healthcare services and programs of VCT centers can help medical teams deliver the desired services to clients and expand the quality of provided services. In addition, an accurate estimate of service quality status can guide policymakers.

The VCT centers have been only recently established in Iran. Therefore, due to the short-term activity of these centers in Iran, there is an apparent lack of information in this area. The present study is one of the first studies to evaluate the quality of services in VCT centers in Iran.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the quality of healthcare services in VCT centers in Shiraz, Iran, based on a SERVQUAL model from the perspective of clients and assess the service quality gap.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was carried out on 295 PLWH who visited HIV/AIDS VCT centers to receive medical services in Shiraz from March 2019 to February 2020. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (ethics code: IR.SUMS.REC.1398.1085). Of 1,329 active records, 300 cases were randomly selected by systematic sampling. Five patients were excluded from the study due to incomplete information. Willingness to participate in the study, completion of the ethical consent form, and an active record in the center (or regular visits to the center) were considered the inclusion criteria.

3.2. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was calculated using the following formula for finite populations:

where z is the z score, ε is the margin of error, N is the population size, and

3.3. Variables and Measurements

For the assessment of the quality of services for clients visiting the VCT centers, the SERVQUAL questionnaire was completed in the waiting period before and after delivering the requested services. This questionnaire, which was developed by Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry, contained an expectation section and a perception section; there were 22 matching statements for expectations and perceptions. The statements in both sections were categorized into six dimensions, namely tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy, and accessibility (18). The Persian translation of this questionnaire was adapted and checked for reliability and validity in the Iranian population by Heidarnia et al. (19)

Responses to the questions of the SERVQUAL questionnaire were scored on a five-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: uncertain, 4: agree, and 5: strongly agree). The difference between the expectation and perception scores was defined as the score of the gap in the quality of services. The gap score was divided into two categories, including scores ≥ 0 (“satisfied”) and scores < 0 (“dissatisfied”) (20). Li et al. confirmed this questionnaire’s face and content validity and calculated its Cronbach’s α coefficient (97%) to approve its reliability (21). Additionally, to address potential sources of bias, before data collection, the questionnaire was pretested among 30 clients of VCT centers.

3.4. Data Collection

For data collection, face-to-face interviews with the participants were conducted by trained staff in a private place upon their arrival at VCT centers to receive healthcare services and after that. The questionnaire used in the present study consisted of two major sections. The first section included the demographic characteristics of the participants. The second section consisted of the SERVQUAL questionnaire to assess the quality of services. The demographic characteristics of the subjects included gender, age, frequency of visits to VCT centers, educational status, marital status, and employment status.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD), and qualitative variables were expressed in numbers and percentages. The independent-sample t-test, paired t-test, Pearson’s correlation test, and one-way analysis of variance were used to determine the associations between the participants’ characteristics and the expected/perceived quality of services. Moreover, simple and multiple logistic regression analyses were used to determine the factors associated with the participants’ satisfaction. The data were analyzed in SPSS software (version 26; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at less than 0.05.

4. Results

In the present study, a total of 295 PLWH were enrolled, including 161 (54.6%) male and 134 (45.4%) female patients. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants stratified by gender. The mean scores of expected and perceived service qualities were 4.81 (95% CI: 4.741 - 4.864) and 3.96 (95% CI: 3.901 - 4.019) in male subjects and 4.85 (95% CI: 4.80 - 4.89) and 4.09 (95% CI: 4.01 - 4.135) in female subjects, respectively. Table 2 shows the associations between the participants’ characteristics and the expected/perceived service quality.

| Characteristics | Male (N = 161) | Female (N = 134) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 42.17 ± 7.95 | 40.34 ± 9.05 | 0.0656 |

| Educational status | |||

| Illiterate | 1 (0.6) | 5 (3.7) | 0.102 |

| Primary school | 50 (31.1) | 40 (29.9) | 0.291 |

| Middle school | 72 (44.7) | 49 (36.6) | 0.03 |

| Secondary school | 29 (18.0) | 32 (23.9) | 0.7 |

| University | 9 (5.6) | 8 (6.0) | 0.808 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 69 (42.9) | 12 (9.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Married | 76 (47.2) | 75 (56.0) | 0.935 |

| Divorced or widowed | 16 (9.9) | 47 (35.1) | 0.0001 |

| Frequency of visits to VCT centers | |||

| Once a week | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.5) | 0.65 |

| Every 2 weeks | 5 (3.1) | 1 (0.7) | 0.102 |

| Every month | 107 (66.5) | 84 (62.7) | 0.096 |

| Every 2 months | 44 (27.3) | 42 (31.3) | 0.82 |

| More than every 2 months | 2 (1.2) | 5 (3.7) | 0.25 |

| Employment status | < 0.0001 | ||

| Unemployed | 58 (36.0) | 114 (85.1) | |

| Employed | 103 (64.0) | 20 (14.9) |

Characteristics of Participants Stratified by Gender a

| Variables | Expected Service Quality | Perceived Service Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P-Value | Mean ± SD | P-Value | |

| Gender | 0.042 a | |||

| Male | 4.8 ± 0.39 | 0.219 | 3.98 ± 0.37 | |

| Female | 4.85 ± 0.26 | 4.07 ± 0.37 | ||

| Frequency of visits to VCT centers | 0.596 | 0.032 a | ||

| Once a week | 4.97 ± 0.04 | 4.35 ± 0.22 | ||

| Every 2 weeks | 4.86 ± 1.34 | 3.66 ± 0.42 | ||

| Every month | 4.83 ± 0.27 | 4.03 ± 0.27 | ||

| Every 2 months | 4.81 ± 0.47 | 4.00 ± 0.38 | ||

| More than every 2 months | 4.65 ± 0.40 | 3.88 ± 0.21 | ||

| Educational status | 0.239 | 0.065 | ||

| Illiterate | 4.91 ± 0.09 | 4.33 ± 0.33 | ||

| Primary school | 4.82 ± 0.27 | 4.01 ± 0.41 | ||

| Middle school | 4.77 ± 0.44 | 4.04 ± 0.33 | ||

| Secondary school | 4.89 ± 0.23 | 4.01 ± 0.36 | ||

| University | 4.84 ± 0.23 | 3.82 ± 0.48 | ||

| Marital status | 0.085 | 0.861 | ||

| Single | 4.75 ± 0.51 | 4.01 ± 0.38 | ||

| Married | 4.85 ± 0.25 | 4.02 ± 0.38 | ||

| Divorced or widowed | 4.84 ± 0.24 | 4.04 ± 0.35 | ||

| Employment status | 0.296 | 0.005 a | ||

| Unemployed | 4.84 ± 0.25 | 4.07 ± 0.37 | ||

| Employed | 4.80 ± 0.44 | 3.95 ± 0.37 | ||

Association Between Participants’ Characteristics and Expected/Perceived Quality of Services

As shown in Table 2, there was no significant association between gender and the expected service quality (P = 0.219); nevertheless, gender had a significant association with the perceived service quality (P = 0.042). The participants’ age had a significant association with the expected (P = 0.017) and perceived (P = 0.026) service quality. On the other hand, there was no significant association between the expected service quality and the frequency of visits to VCT centers or employment status. However, the frequency of visits to the VCT centers and employment status were associated with the perceived service quality. The results showed no significant relationship between the expected/perceived service quality and educational or marital status (Table 2).

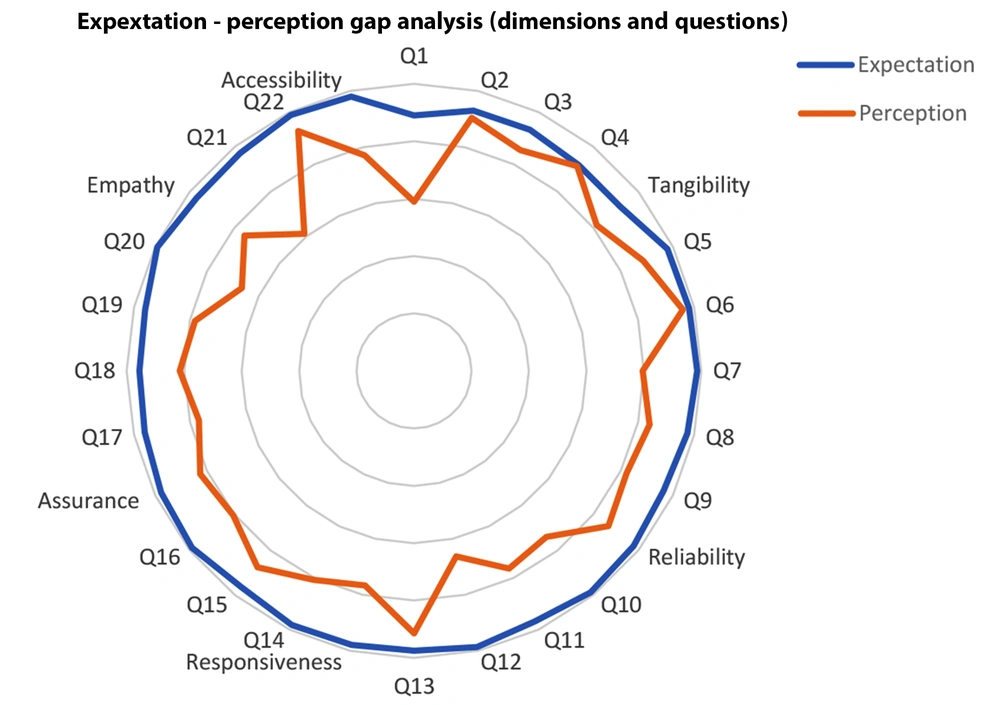

In this study, 285 (96.6%) patients were not satisfied with the quality of delivered services. According to simple logistic regression analysis, there was no significant association between the participants’ characteristics and the level of satisfaction (Table 3). A paired t-test was carried out to determine significant differences in the mean values of expected and perceived service quality in VCT centers. Table 4 shows the mean (SD) of expectation, perception, and gap scores, in addition to t-values and P-values, obtained by evaluating each question related to each dimension. According to the results, there was a significant difference in the expected and perceived service quality of VCT centers in all dimensions. The average scores of expected and perceived service quality were 4.82 and 4.02, respectively. The gap between the expected and perceived service quality was -0.80. The gap scores of responsiveness and empathy dimensions were higher than other dimensions (Table 4). Figure 1 depicts the differences in the expected and perceived service quality (gap scores).

| Variables | Simple Analysis, Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 (0.93 - 1.09) | 0.776 |

| Gender | 0.83 (0.23 - 2.92) | 0.776 |

| Frequency of visits to VCT centers | 1.25 (0.46 - 3.35) | 0.663 |

| Educational status | 1.96 (0.88 - 4.37) | 0.097 |

Factors Associated with Satisfaction Level in Participants (Simple Logistic Regression Analyses)

| Dimensions | Mean ± SD Expectation | Mean ± SD Perception | Mean ± SD Gap | t-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangibility score | 4.59 ± 0.57 | 4.07 ± 0.60 | -0.51 ± 0.80 | 10.95 | < 0.001 a |

| Reliability score | 4.89 ± 0.33 | 4.30 ± 0.46 | -0.58 ± 0.56 | 17.84 | < 0.001 a |

| Responsiveness score | 4.89 ± 0.34 | 3.84 ± 0.62 | -1.04 ± 0.68 | 26.21 | < 0.001 a |

| Assurance score | 4.88 ± 0.33 | 4.14 ± 0.60 | -0.74 ± 0.70 | 18.09 | < 0.001 a |

| Empathy score | 4.83 ± 0.39 | 3.78 ± 0.60 | -1.04 ± 0.71 | 25.2 | < 0.001 a |

| Accessibility score | 4.90 ± 0.36 | 3.85 ± 0.81 | -1.05 ± 0.90 | 19.94 | < 0.001 a |

| Total SERVQUAL score | 4.82 ± 0.34 | 4.02 ± 0.37 | -0.80 ± 0.49 | 27.6 | < 0.001 a |

Mean Scores of Participants’ Perceptions, Expectations, and Gap of Service Quality in SERVQUAL Dimensions

5. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the quality of HIV/AIDS services in Iran and investigate its relationship with patients’ sociodemographic characteristics. The main findings of the study are discussed in this section.

The present study did not indicate any significant relationship between the patients’ sociodemographic status and level of satisfaction with the quality of services; this finding is consistent with the results of a study by Derisi et al. (22). Conversely, the patient’s gender, age, frequency of visits to VCT centers, and employment status had significant effects on the patients’ perception of service quality. In this regard, the results of a study by Mahyapour Lori showed that a higher level of education in patients led to a greater gap between expectations and perceptions of service quality (23). Therefore, this factor should always be considered when providing services for clients, as different individuals have different viewpoints of service quality, and services that might satisfy a certain group might not be satisfactory for other groups.

In the present study, according to the SERVQUAL model, patients' expectations were higher than their perceptions in all dimensions of service quality, and evaluation of their perceptions indicated their dissatisfaction. Similar to the current study, multiple studies have reported large gaps between the expectations and perceptions of service quality in all dimensions (24-30). The largest gap was observed in the dimensions of responsiveness, empathy, and accessibility; nevertheless, the smallest gap was related to tangibility. In contrast, some studies reported the smallest gap in responsiveness (24) and empathy (29). This discrepancy can be due to numerous factors, such as different characteristics of the patients, health organizations, and services.

Some items of the responsiveness dimension, including “services are provided to patients promptly” and “the waiting time to receive the service is less than one hour”, produced large negative gaps in comparison to other items; therefore, few items of this dimension need improvements. Based on the findings, VCT centers need to focus on educating their staff about the basic needs of the patients. Additionally, relevant authorities should pay more attention to patients’ rights and be more responsible toward them. Moreover, the staff of centers, who are in direct contact with the clients and have the greatest impact on the quality of services and patient satisfaction, should be prioritized for participation in service quality improvement programs (18). According to a study conducted in Shiraz on patients of Shiraz teaching hospitals in 2003, the largest gap was related to responsiveness, which is similar to the results of the present study; therefore, the responsibility remains a major problem in service quality (31). This remarkable gap in responsiveness, observed in the current study, is consistent with the findings of studies by Aghamolaei in the southern region of Iran (32), Al-Momani in Saudi Arabia (33), and Derisi in Iran (22).

The highest expectation score was related to the empathy dimension (“the specific needs of patients are taken into account and understood”). Moreover, the low perceived score indicated a large gap in the empathy dimension, which shows that patients expected VCT centers to be more patient-centered and prioritize patients’ problems. They also expected the staff to consider their individual needs, cultural backgrounds, and preferences. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, patients expect VCT centers to help them meet their psychological and physiological needs (34). The patients also expect the staff to pay more attention to them. Therefore, special attention to these issues can produce better outcomes, such as higher levels of patient satisfaction, improved communication between the physician and patient, improved therapeutic compliance, and greater recovery rates (35, 36). The aforementioned results are consistent with the results of studies by Rakhshani in Iran (37), Hatam in Iran (29), and Ga in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania (25). Similarly, a recent systematic review in Iran indicated the largest gap in the empathy dimension (38).

In the present study, the tangibility and reliability dimensions had the lowest gap scores; therefore, the VCT centers had better performance in these dimensions than others. However, the largest gap was related to the physical environment of the counseling center. Accordingly, the gap in tangibility can be improved by the renovation of the center, keeping a clean environment, proper use of signboards, use of neat staff uniforms, and keeping accurate patient records. In addition, in terms of reliability, clients’ trust and confidence can be increased by better handling their problems and delivering accurate and appropriate services in the promised time (18).

The present study revealed the challenges of healthcare service quality in VCT settings from the viewpoint of PLWH to find new strategies for health policymakers. However, there are some limitations to this study. Firstly, in numerous field studies on sensitive subjects, such as HIV/AIDS, affected people are less inclined to participate. Secondly, the accuracy of responses is affected by the educational level of PLWH. Thirdly, the interviews were inevitably conducted right before and after the delivery of healthcare services in VCT centers, which could produce bias in the participants’ responses. To overcome these shortcomings, the researchers recruited an expert with good communication skills to create a friendly environment during the interviews and explain the questions to the participants to increase their cooperation.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of the present study showed a significant gap between the expected and perceived quality of HIV/AIDS services in VCT settings. It seems that the improvement of the providers’ communication skills is the best approach to reduce dissatisfaction with the empathy dimension in PLWH. Responsiveness was another disappointing dimension from the participants’ viewpoint, which could be addressed by improving the process of service delivery and increasing the number of healthcare providers. Finally, it is necessary to consider the education and involvement of PLWH in the improvement of their care. Further facility-based studies are recommended to better understand the causes of low satisfaction with empathy and responsiveness dimensions.