1. Background

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are a leading cause of death worldwide. One popular diagnostic tool for heart conditions is the non-invasive cardiac stress test (NCST), specifically the exercise stress test (EST) (1). The EST diagnoses obstruction or narrowing of coronary arteries when chest pain and changes in pulse rate (PR), blood pressure (BP), and electrocardiogram (EKG) have occurred (2). Despite being low-cost and offering immediate results, the EST has some limitations, including lower diagnostic accuracy in women, those with left ventricular hypertrophy, and digoxin users (1, 3). Moreover, it may cause anxiety and distort results in patients who are unfamiliar with testing procedures or have had unpleasant experiences with other cardiac tests (4, 5). Since anxiety disorders are common among CVD patients, reducing anxiety and preparing patients before the test is crucial (6).

Educating patients through face-to-face interviews effectively reduces anxiety before cardiac surgery or hospital discharge (7). However, its drawbacks, such as being time-consuming and requiring specific time and place, have resulted in a growing trend towards virtual and online alternatives (8). Multimedia education makes learning easier and more attractive (9). This method has shown promise in reducing anxiety levels among patients undergoing cardiac catheterization (10). Furthermore, with the advance of technology and the availability of cell phones for almost everyone, educating patients through SMS has been suggested for increasing awareness and disease control in patients with coronary heart disorders (11). The effectiveness of various educational interventions in reducing patients’ anxiety before cardiac surgery has been confirmed previously (12). Nonetheless, the effect of different educational methods on the anxiety levels of EST candidates has not been evaluated so far.

2. Objectives

We aimed to compare the impact of education via routine face-to-face, interactive multimedia, and SMS on anxiety as a primary objective and BP and PR as secondary objectives in EST candidates.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study was a double-blinded paralleled randomized controlled trial conducted between August 2017 and May 2018 in the heart clinics affiliated with Larestan University of Medical Sciences, Larestan County, south of Iran. Among 150 patients scheduled for the EST, 144 eligible patients voluntarily filled out and signed the informed consent form after informing them about the objectives. This study is approved under the ethical approval code of IR.SUMS.REC.1396.18. The protocol was registered as IRCT2017042933689N1 in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials.

3.2. Sample Size Calculation

Based on a similar study (13), the sample size was estimated using the mean and standard deviation of the total anxiety score (primary outcome) in the intervention (89.4 ± 19.5) and control (107 ± 24.2) groups, considering the power of 95% and α of 0.05. Using STATA software and the following command, sampsi 89.4 107, sd1(19.5) sd2(24.2) a (.05) p (.95), a minimum sample size of 41 in each group was determined for the study. We enrolled 4 - 5 additional patients in each group for compensating probable attrition.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were being literate, having the age of 20 - 60 years, being a candidate for the EST for the first time, owning a cell phone or a personal computer and having the ability to use them, and having an anxiety score of ≥ 16 (moderate to severe). Any patient who used tranquilizers or other anxiety medications or had an experience of previous EST was not enrolled in the study.

3.4. Randomization and Intervention Blindness

Patients were randomly allocated to three groups using random allocation software and permuted block randomization (block size of 6): One control group (face-to-face education, n = 47) and two intervention groups: Multimedia (n = 48) and SMS (n = 49). All study participants and outcome assessors were blind to the group allocations. The patients were assessed on different days to have no contact with each other and avoid data contamination.

3.5. Interventions, Follow-up, and Data Collection

The study enrolled 144 patients eligible for the EST. One week before EST, the control group received a 30-minute routine face-to-face education by a hospital researcher covering CST definition, test methods, preparation, and adverse effects. Intervention group 1 received an interactive multimedia CD containing 30-minute materials, such as text, audio, video, and animation, with similar content one week before the EST to be watched at home multiple times. Intervention group 2 received the same content via 14 text messages sent to their cell phones for one week, with one SMS in the morning and one in the evening. The educational content was prepared by researchers based on the literature and underwent e-content development at the virtual school of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences - the center of excellence for e-learning in medical sciences (14).

The participants were asked to complete the Beck’s Anxiety Inventory (BAI), a 21-item self-report measure on clinical anxiety (15). In this questionnaire, the subjects chose one of the four options for each question about the most common anxiety symptoms (mental, physical, and panic). Each question scored from 0 to 3, and the sum scores showed the severity of anxiety (0 - 7: minimal, 8 - 15: mild, 16 - 25: moderate, and 26 - 63: severe). The Persian version of the BAI has been validated by Kaviani and Mousavi (16). The intra-class correlation between the BAI scores and clinical evaluation of anxiety showed an acceptable validity (r = 0.72), appropriate test-retest reliability (r = 0.83), and acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92).

At the baseline (before providing education), the researcher recorded demographic features, patient’s symptoms (including angina pectoralis, dyspnea, and shoulder pain), history of hospital admission due to cardiac symptoms, and the BAI questionnaire for all the included patients. The BAI was also completed for each participant immediately before the EST. A co-researcher examined the patients’ PR and right-arm BP a week before, immediately before, and at the end of the first stage of the EST. If a patient had unstable vital signs before the test, the EST was not performed, and the patient was excluded from the study. If the vital signs were within the normal range and the EKG had no abnormal features, the EST was performed with a gradually increasing speed. At the end of each stage of the EST, the patients’ PR, BP, and EKG were checked. If the patient had changes in EKG, chest pain, and/or shortness of breath during the test, the test ceased, and the patient was excluded from the study.

3.6. Statistical Analyses

The statistical analyses were conducted by IBM SPSS version 21.0. The data were described by frequency (percentage) or mean ± standard deviation (SD) based on the variable’s type. The normal distribution of the quantitative data was checked by the Shapiro-Wilks test. The numeric variables were compared among the three groups using one-way ANOVA, and the significant differences were compared pairwise using Tukey’s post hoc test. The categorical variables among the groups were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test based on the number of participants in the subgroups. The measured intervals were compared using a paired t-test or repeated-measures ANOVA, depending on the number of intervals measured. The level of significance for all tests was set at 0.05.

4. Results

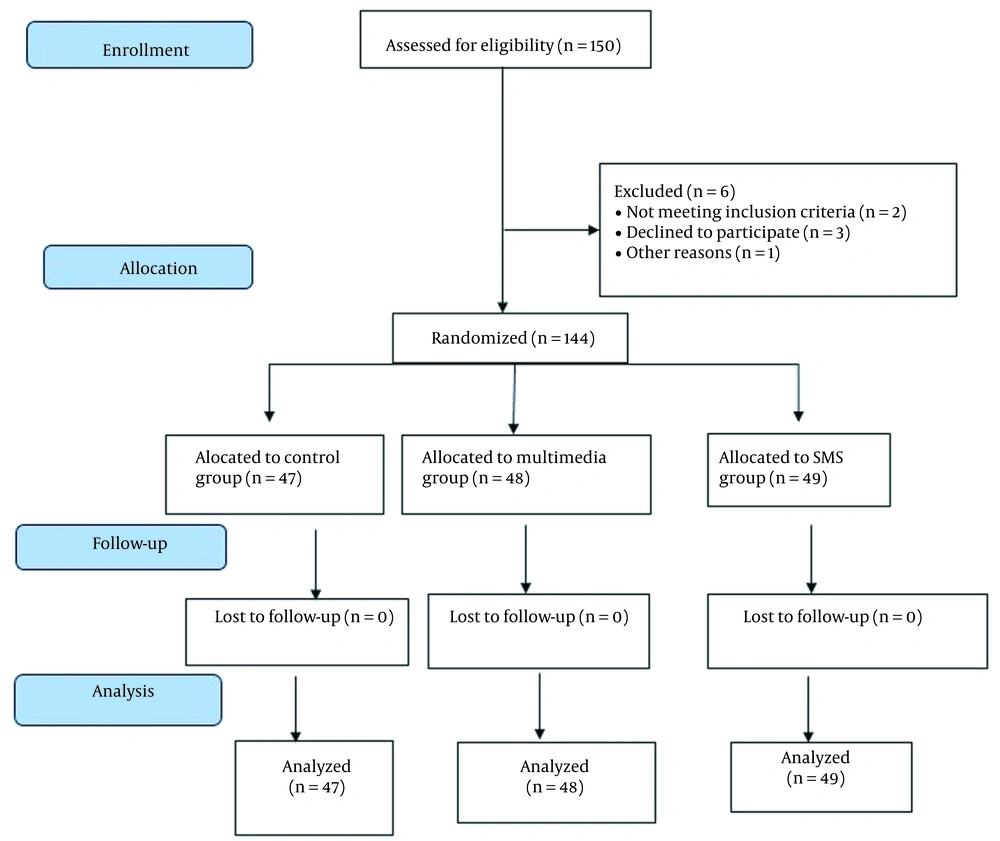

The CONSORT flow diagram of our study is shown in Figure 1. The three groups had no significant differences concerning the distribution of basic variables (Table 1).

| Variables | Face-to-Face (n = 47) | Multimedia (n = 48) | Text Messaging (n = 49) | Total (n = 144) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 44.96 ± 9.04 | 43.96 ± 9.37 | 44.59 ± 9.26 | 44.50 ± 9.17 | 0.867 b |

| Sex | 0.838 c | ||||

| Female | 36 (76.6) | 36 (75.0) | 35 (71.4) | 107 (74.3) | |

| Male | 11 (23.4) | 12 (25.0) | 14 (28.6) | 37 (25.7) | |

| Marital status | 0.630 d | ||||

| Single | 10 (21.3) | 11 (22.9) | 13 (26.5) | 34 (23.6) | |

| Married | 32 (68.1) | 32 (66.7) | 27 (55.1) | 91 (63.2) | |

| Divorced/widowed | 5 (10.6) | 5 (10.4) | 9 (18.4) | 19 (13.2) | |

| Education level | 0.846 c | ||||

| Elementary school | 19 (40.4) | 22 (45.8) | 23 (46.9) | 64 (44.4) | |

| High-school graduate | 14 (29.8) | 13 (27.1) | 16 (32.7) | 43 (29.9) | |

| Academic degree | 14 (29.8) | 13 (27.1) | 10 (20.4) | 37 (25.7) | |

| Occupation | 0.887 d | ||||

| Unemployed | 9 (19.1) | 12 (25.0) | 10 (20.4) | 31 (21.5) | |

| Employed | 14 (29.8) | 12 (25.0) | 11 (22.4) | 37 (25.7) | |

| Retired/housewife | 24 (51.1) | 24 (50.0) | 28 (57.1) | 76 (52.8) | |

| Symptoms | 0.682 c | ||||

| Angina pectoralis | 25 (53.2) | 31 (64.6) | 25 (51.0) | 81 (56.3) | |

| Dyspnea | 12 (25.5) | 8 (16.7) | 12 (24.5) | 32 (22.2) | |

| Shoulder pain | 10 (21.3) | 9 (18.8) | 12 (24.5) | 31 (21.5) | |

| History of admission | 0.811 c | ||||

| Yes | 14 (29.8) | 12 (25.0) | 12 (24.5) | 38 (26.4) | |

| No | 33 (70.2) | 36 (75.0) | 37 (75.5) | 106 (73.6) |

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or No. (%).

b The results of one-way ANOVA

c The result of chi-square test

d The results of Fisher’s exact test

The baseline BAI scores showed no significant difference between the three study groups (P > 0.05; Table 2). Comparing the baseline and post-intervention BAI scores in each group indicated no difference in the control group, while both intervention groups showed a decreased post-intervention anxiety score (P < 0.001). Post-intervention BAI was significantly lower in the SMS group than in control (P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = -1.09, 95% CI; -1.52 to -0.66) and multimedia (P < 0.001, Cohen’s d = -0.83, 95% CI; -1.25 to -0.42; Table 2) groups. There was no significant difference between the face-to-face and multimedia groups (P = 0.454).

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

b The results of paired t-test

c Significant difference was observed between face-to-face and text messaging groups based on Tukey’s Post-hoc test (P < 0.001)

d Significant difference was observed between multimedia and text messaging groups based on Tukey’s Post-hoc test (P < 0.001)

e The result of one-way ANOVA

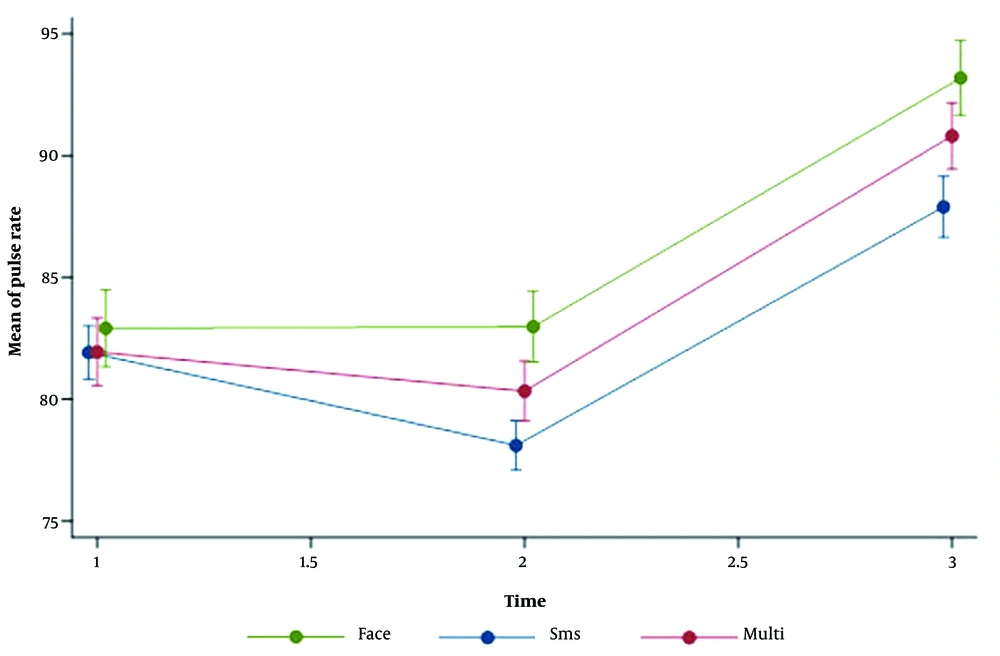

In terms of secondary outcomes, the results of the repeated-measures ANOVA indicated a significant group-time interaction effect for systolic BP (P = 0.030) and PR (P < 0.001). Subsequently, a one-way ANOVA was conducted, revealing that patients who received SMS-based education had lower PR before (P = 0.017) and at the end of the first stage of EST (P = 0.022) than those who received face-to-face education. Additionally, there were significant differences in systolic BP and pulse rate across all groups between different time points (P < 0.001). The effect of time on diastolic BP was also found to be significant in the multimedia and SMS groups. Regarding specific time points, systolic and diastolic BP levels were significantly higher at the end of the first stage of EST than other measurements in the face-to-face and multimedia groups. However, in the SMS group, the levels of systolic and diastolic BP and pulse rate were significantly lower immediately before EST compared to other times (Table 3). The trend of the changes in PR in the three study groups is depicted in Figure 2.

| Variables | Face-to-Face | Multimedia | Text Messaging | P-Value c | P Value d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Group | Time d Group | |||||

| Systolic blood pressure | < 0.001 | 0.439 | 0.030 | ||||

| One week before the intervention | 131.40 ± 19.27 A | 127.25 ± 17.87 A | 130.31 ± 14.67 A | 0.481 | |||

| Immediately before EST | 130.28 ± 16.52 A | 126.02 ± 16.35 A | 126.41 ± 14.16 B | 0.347 | |||

| At the end of the first stage of EST | 134.19 ± 15.64 B | 130.42 ± 15.50 B | 130.71 ± 13.26 A | 0.389 | |||

| P-value (within) d | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Diastolic blood pressure | < 0.001 | 0.513 | 0.086 | ||||

| One week before the intervention | 80.04 ± 9.99 | 79.23 ± 9.89 A | 78.69 ± 9.40 A | 0.794 | |||

| Immediately before EST | 78.85 ± 8.51 | 78.69 ± 9.33 A | 76.06 ± 9.40 B | 0.241 | |||

| At the end of the first stage of EST | 80.62 ± 13.63 | 82.08 ± 8.84 B | 79.26 ± 8.98 A | 0.432 | |||

| P-value (within) d | 0.298 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Pulse rate | < 0.001 | 0.123 | < 0.001 | ||||

| One week before the intervention | 82.91 ± 10.84 A | 81.94 ± 9.70 A | 81.92 ± 7.66 A | 0.842 | |||

| Immediately before EST | 82.98 ± 9.99 A | 80.33 ± 8.52 A | 78.10 ± 7.15 B | 0.024 e | |||

| At the end of the first stage of EST | 93.19 ± 10.61 B | 90.81 ± 9.46 B | 87.90 ± 8.79 C | 0.039 e | |||

| P-value (within) d | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

Abbreviation: EST, exercise stress test.

a Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

b Different capital letters show significant differences between different times in each group using Bonferroni correction.

c Differences between groups according to the ANOVA test

d Repeated-measures ANOVA test

e Significant differences were found between face-to-face and text messaging groups using Tukey’s post hoc test.

5. Discussion

We found a significant reduction in anxiety scores in the SMS group compared to the control and multimedia groups. A very strong effect of the intervention was observed in comparing SMS and control groups. Nevertheless, multimedia education failed to affect anxiety compared to the control group significantly.

Research suggests that anxiety and stress, particularly before cardiac tests or surgery, are important conditions in cardiac patients (17). The sources of anxiety among these patients include the fear of death, discomfort from previous tests, and apprehension about the upcoming interventions (18). Educating patients about the procedure is an effective method for reducing anxiety. This can be done through various strategies, such as providing booklets or face-to-face explanations (12).

Multimedia education has been suggested as an appropriate measure to reduce patients’ anxiety/pain in various settings, including patients admitted to the coronary intensive care unit (19, 20) and candidates for cerebral angiography (21). This educational method has several advantages, such as time efficiency, ease of use, cost-effectiveness, and the opportunity to repeat the educational content based on the learner’s desire (19). However, we detected no effect of multimedia education on patients’ anxiety. The observed inconsistencies could be due to the differences in the selected cardiac procedure, the prepared contents, the control group, and the assessment tool for evaluating anxiety. The effectiveness of SMS education on patients’ anxiety, proposed by the present study, is consistent with other studies, suggesting the favorable effect of this method on improved patient care (22, 23).

We also found that traditional face-to-face intervention did not adequately reduce patient anxiety. This could be attributed to the inherent shortcomings of in-person education, as learners may have difficulty comprehending and retaining information presented during a single verbal session (24). However, providing multimedia and SMS education before the CST allowed patients to review the material repeatedly, leading to better outcomes. Other studies have also confirmed the inefficacy of face-to-face education for percutaneous intervention (PCI) candidates in reducing anxiety (25), which supports our findings.

We also found no significant differences in the BP among the three groups. One week after the education, the SMS method led to a lower PR than the face-to-face group, which can be attributed to the passive education in the face-to-face group. Previous studies also have shown a reducing effect of video education on the hemodynamic fluctuation of PCI candidates (26, 27). The educational interventions can reduce anxiety’s impact on the hemodynamic fluctuation in the patient and enable a more accurate diagnosis of the cardiac disease by the EST.

Our study had several limitations. Our SMS platform was one-way, and we could not verify message receipt. Furthermore, the results of this study cannot be generalized to the whole population, especially those with lower socioeconomic status, as we only considered patients with access to cell phones or computers and literacy skills. Furthermore, our study had a small sample size in each group, mainly because of the several inclusion criteria considered for reducing the effect of confounders and higher accuracy of the results.

5.1. Conclusions

Given the probable effectiveness of education via text messages and multimedia in decreasing patients’ anxiety scores, we recommend using these methods to prevent anxiety before the EST.