1. Background

Physician training encompasses much more than acquiring knowledge of basic sciences, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and disease management. Medical students should also learn skills such as interpersonal communication, empathy, self-care, and professional identity (1). Professional identity has been a longstanding concept in medicine (2). It can be defined as the subjective sense of belonging to a particular professional group (3, 4). In medicine, professional identity refers to how a doctor perceives themselves as a physician (5). Cruess et al. described professional identity as a symbol developed over time, in which the norms and values of the medical profession are internalized. This internalization results in thinking, acting, and feeling like a physician (6).

The development of professional identity is subjective and influenced by various factors, including social, demographic, and personality aspects (3). According to Cruess et al., identity formation consists of three domains. The first domain is individual identity, which includes personal characteristics, self-esteem, and life experiences. The second domain is relational identity, which involves relationships with friends, family members, mentors, and colleagues. The third domain is collective identity, relating to the social groups a person wishes to join or belongs to (7). Crossley and Vivekananda-Schmidt identified that professional identity is influenced by three factors: (1) profession-specific tasks, (2) 'generic attributes,' and (3) 'interpersonal tasks' (3). Pratt et al. highlighted socialization, identity work, and career/role transitions as different aspects of identity construction (8). According to Tagawa's study, professional identity formation involves self-control as a professional, awareness of being a medical doctor, reflection as a medical practitioner, execution of social responsibility, and both external and internal self-harmonization. However, medical learners differ in their experiences and development processes of professional identity (9).

These findings highlight the varied experiences in the development of professional identity. Generally, professional identity is influenced by the learning environment, personal characteristics, role models and mentors, clinical and non-clinical experiences, peer attitudes, healthcare professionals (7), life experiences, socialization in academic and clinical settings, and technological and societal factors (5). There may be significant differences in professional identity formation between Western and Eastern cultures, potentially due to factors such as religion and beliefs (10). In the field of medical education, numerous factors may create barriers for some students while offering opportunities for others, leading to inequity in different parts of the world. While one medical student may receive support and guidance, another may face challenges on the path to becoming a physician (11).

Professional identity is a vital component of medical education (3-12). It influences the future practice of medical students in the workplace. Potential challenges associated with healthcare settings (10) and delays in acquiring this essential competency can hinder the successful transition from medical student to physician (3). The lack of clarity in professional identity can significantly impact a practitioner's confidence in expressing their professional opinions (12). Therefore, one of the key objectives of the medical education curriculum is to facilitate the development of professional identity formation in students (8).

Numerous studies have explored physicians' professional identity (8, 13-16). The frameworks for professionalism that lead to professional identity formation vary across cultures, making the journey to becoming a doctor dependent on the specific context, culture, and country. Cultural differences in professional identity formation may relate to physician-patient communication, healthcare structure, and the culture within medical education (17).

A critical issue in professional identity formation is understanding how different students, influenced by factors such as gender, age, race, and ethnicity, overcome barriers to attain professional identity. The various circumstances that influence professional self-identity formation are under-studied (18).

Despite the global interest in professional identity, there is concern about the lack of a valid and reliable Persian scale to measure professional identity within Persian and Iranian culture. Validating such tools in different societies could significantly aid in applying these concepts in vocational training. One of the questionnaires used for measuring this ability is the Professional Self-identity Questionnaire (PSIQ).

2. Objectives

This study aims to determine whether the PSIQ, originally developed within Western culture, can be adapted to the Iranian context.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This quantitative study uses a descriptive design conducted on medical students (years 4 - 7) at Shiraz Medical School in 2019. The PSIQ consists of nine items, and to assess the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, 180 students were randomly included in the study. Each year, forty-five medical students were selected using a stratified sampling approach. A total of 175 medical students (years 4 - 7) with a mean age of 23.52 ± 1.54 completed the questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 87.5%.

3.2. Questionnaire

There are validated methods developed for assessing professional identity, and one of the tools used in the present study is the PSIQ. This tool was developed in 2009 by Crossley and Vivekananda-Schmidt, who examined the curricular features that contribute to developing a professional identity. The panel of experts revised and modified the translation. The Persian version of the survey was distributed to eight faculty members in the Department of Medical Education. They were asked to rate the items' relevance and thoroughness to assess their face and content validity. The items' Content Validity Index (CVI) exceeded 0.79, and the questionnaire's overall content validity ratio (CVR) exceeded 0.75, according to the Lawshe table. To assess the quantitative face validity of the questions, we used the item impact method to calculate impact scores for each question. The results indicated that each item had an impact score greater than 1.5, suggesting that the questions should undergo additional analysis.

The instrument was designed to reflect areas of professional activity common to the health professions, within which professional self-identity would operate. This questionnaire includes nine items that indicate three domains. The latent constructs proposed by these three factors are: "Profession-specific tasks" (conducting assessments, using records, dealing with emergencies, and teaching), "generic attributes" (cultural awareness, ethical awareness, and reflection), and "inter-personal tasks" (teamwork and communication). Each item is rated on a 6-point Likert scale. This instrument measures the sense of students in identifying their present position on a range between 'first-day student' and 'qualified doctor' (1 point as "equivalent to the first day of clinical practice" and 6 points as "qualified doctor"). The internal consistency of the original PSIQ, measured by Cronbach's alpha, was 0.93. As an indication of validity, more experienced medical students scored higher on the PSIQ than less experienced students (3). The present questionnaire has been used in pharmacy (19), medicine (4-20), dentistry (4), and nursing (20) professions.

3.3. Procedure

In the first step, written permission to use the PSIQ was obtained by email from the developer of the questionnaire. The PSIQ was initially translated into Persian by two independent translators whose first language was Persian. The translated versions were then reviewed to reach an agreement. The translated PSIQ was reviewed for variations using the back-translation method, with the help of two independent translators who were native English speakers. These back translators were blinded to the original PSIQ, meaning they had no access to the original English version (21). The translations were compared to the original English version to ensure conceptual similarity.

The final Persian translation was reviewed by an expert committee of eight members, including medical doctors familiar with medical education and professionalism, methodologists, language professionals, and the forward and backward translators. The committee assessed whether the translation reflected the same ideas as the original version. Each committee member provided comments on items they found unclear. The participants also rated the relevance, precision, practicality, and clarity of the questionnaire items on a scale from 1 to 5. Based on the review results, the Persian translation was revised to ensure cultural comparability. Finally, grammatical and spelling errors were checked, and the final Persian translation was developed.

We distributed the Persian-translated version of the PSIQ to final-year medical students. The purpose of the PSIQ was explained to the students, and it was clarified that the results would be used anonymously for research purposes only. All items were scored on a six-point Likert scale (from 1 as the lowest to 6 as the highest). The raw subscale scores were transformed into values ranging from 3 to 18, with higher scores indicating better task performance.

3.4. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Before commencing the study, ethical approval was obtained from the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences Research Ethics Committee (code: IR.SUMS.MED.REC.1398.382). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and data anonymity was guaranteed. Medical students were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time, for any reason, without penalty. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

3.5. Statistical Analyses

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with varimax rotation was used to assess the construct of the PSIQ. All factors (items) had eigenvalues greater than 1.00. Ordered-categorical confirmatory factor analysis (CCFA), initially designed for the Likert response scale, was employed to evaluate the construct validity of the questionnaire. By using CCFA, we could measure how well our data aligned with the extracted domains. In this study, we investigated whether the hypothesized three-factor model fit the data well.

Three criteria were used to assess the goodness of fit of the model: The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the comparative fit index (CFI). CFI values greater than 0.9 indicate a good fit, while values above 0.95 indicate an excellent fit. For the TLI, values greater than 0.90 are acceptable, and those above 0.95 represent a good fit. An RMSEA value less than 0.08 indicates an acceptable fit, while a value below 0.05 indicates an excellent fit (22).

To assess the internal reliability of the PSIQ, we calculated Cronbach's alpha for each subscale. A coefficient alpha equal to or greater than 0.70 was considered indicative of satisfactory reliability for the scale score (23, 24).

Statistical data analysis was conducted using the diagonal weighted least square (DWLS) estimation procedure in the lavaan package in R.3.6.2 software. Additionally, the path diagram was plotted using the semPlot package in this statistical software.

4. Results

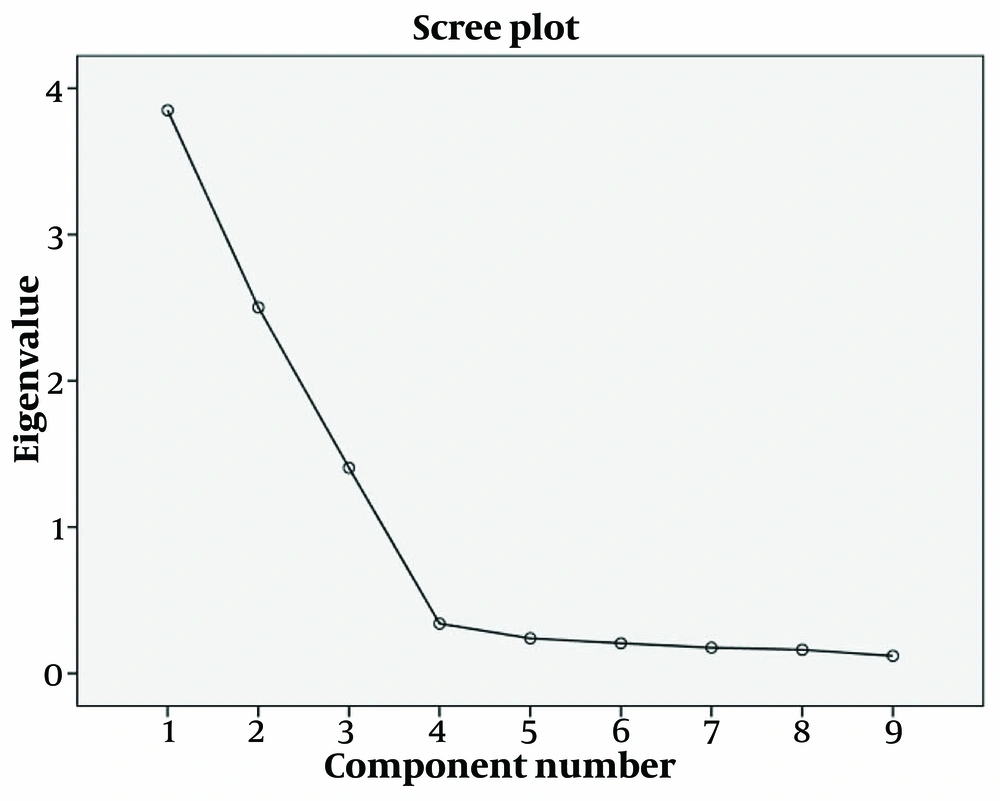

A total of 175 participants completed the questionnaires (male: Seventy-seven, female: Ninety-eight). The mean age of the participants was 23.52 ± 1.54 years. The scree plot graphically displayed the eigenvalues of each factor and suggested that three predominant factors accounted for 86.19% of the variance, as shown in Figure 1.

The EFA results are displayed in Table 1. Three factors with an eigenvalue of > 1.00 were identified from all nine items of the PSIQ, accounting for 86.19% of the dataset's variance. This was similar to the original PSIQ version in terms of how the items were loaded onto the factors. All the PSIQ items had a factor loading higher than 0.40 on the corresponding domain.

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.93 | 0.18 | -0.06 |

| 2 | 0.90 | 0.19 | -0.05 |

| 3 | 0.91 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| 4 | 0.15 | 0.91 | 0.17 |

| 5 | 0.16 | 0.90 | 0.08 |

| 6 | 0.22 | 0.89 | 0.20 |

| 7 | -0.01 | 0.13 | 0.92 |

| 8 | -0.03 | 0.11 | 0.93 |

| 9 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.87 |

Results of Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Persian Version of the Professional Self Identity Questionnaire; Rotated Component Matrix

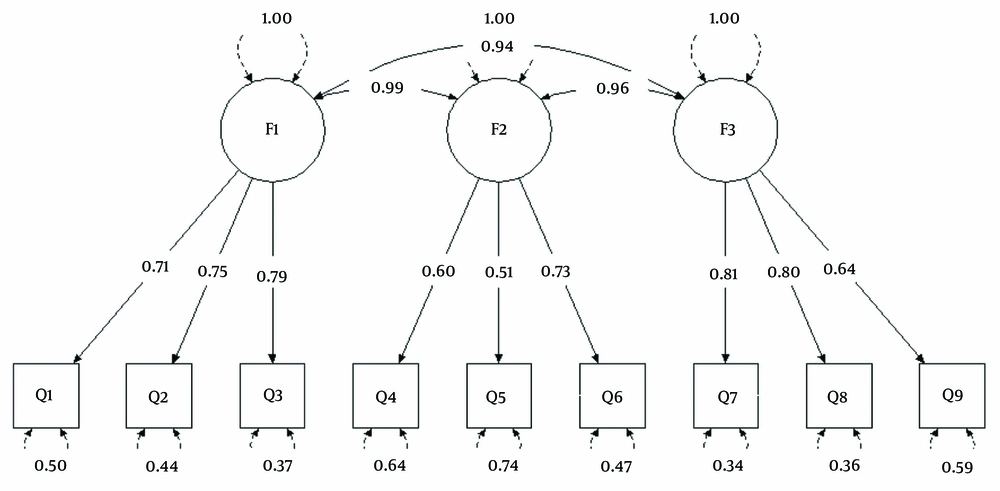

The results of the CCFA indicated that all values of CFI and TLI were greater than 0.95, and the RMSEA index was less than 0.08, supporting the excellent and satisfactory fit of the three-factor CCFA model (Table 2).

| Factor Model | Fit Index | Acceptable Range |

|---|---|---|

| RMSEA | 0.055 | < 0.08 |

| CFI | 0.996 | > 0.95 |

| TLI | 0.994 | > 0.95 |

The Results of the Categorical Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Hypothesized CFA Models

Moreover, the path diagram showed that all of the items (questions) were properly loaded (higher than 0.5) onto the subscales of profession-specific tasks, generic attributes, and interpersonal tasks (Figure 2).

The results of the reliability test for the three dimensions of the questionnaire are shown in Table 2. Cronbach's alpha was measured to assess the internal consistency of the items within each subscale. The results revealed that the Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the three factors—"profession-specific tasks," "generic attributes," and "interpersonal tasks" subscales—were 0.762, 0.622, and 0.747, respectively (P-value < 0.05) (Table 3). The internal consistency of the entire questionnaire, as measured by Cronbach's alpha, was 0.873.

| Factors | No. Items | Cronbach's Alpha | Mean ± SD | (Min, Max) | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profession specific tasks | 3 | 0.762 | 11.61 ± 2.89 | (4,18) | 0.75 |

| Generic attributes | 3 | 0.722 | 12.40 ± 2.60 | (6,18) | 0.69 |

| Interpersonal tasks | 3 | 0.747 | 10.48 ± 3.01 | (3,18) | 0.71 |

| Total | 9 | 0.873 | 11.50 ± 2.98 | (8, 54) | 0.78 |

Cronbach's Alpha, Mean, Standard Deviation, Maximum and Minimum of the Subscales of the PSIQ

5. Discussion

Professional identity is derived from the individual role that people take on in their work (25). It affects perceptions of a medical student's role in medicine (5). Professional identity formation is influenced by students' emotional and spiritual maturity (10-25), leading to the distinction between being a physician and merely practicing medicine (25). It is essential to assess the professional identity status of health professional students using a valid and reliable tool. The present study aimed to examine whether the three-factor model of the original version of the PSIQ could be applied to the Persian translation of this scale.

The findings are consistent with those of Crossley and Vivekananda-Schmidt's study (3). The internal consistency of the Persian version (0.873) and the original version were approximately similar (0.93). The results of the present study confirmed that the PSIQ includes three factors: "Profession-specific tasks," "generic attributes," and "interpersonal tasks" (3). The internal consistency of these three factors was comparable (0.762, 0.747, and 0.622).

The value of RMSEA suggests that the three-factor model fits the participants' covariance matrix. It is a robust and valuable fit index due to its sensitivity to the number of parameters evaluated in this model. In the present study, the CFI, estimated to examine a statistical model's goodness-of-fit, is above the threshold (0.996), indicating that the three-factor model fits the independent model well. TLI was calculated to measure the difference between the χ2 value of the three-factor model and the χ2 value of the null model. The values of the TLI indicate a well-fitting model (26-28).

The values mentioned above demonstrate that the three-factor model fits the sample data. There are three subscales for each factor in the questionnaire.

Interpersonal tasks include teamwork and communication (3). Interprofessional teamwork and communication are prerequisites for professional self-identity (29). A positive attitude toward teamwork is related to the positive self-identity of health professionals (30). As members of a treatment team, developing a professional identity encourages students to collaborate in patient care (5).

Profession-specific tasks include conducting assessments, using records, dealing with emergencies, and teaching (3). Reflecting on medical records is essential for maintaining a professional image (31). Confidence in dealing with emergencies and having a clear understanding of one's educational role appear to be critical determinants of students' attitudes toward qualification (3). Additionally, an effective approach is based on the understanding that the deeper impact of initial teacher education touches upon the professional identity of the student-teacher. Timoštšuk and Ugaste (2005) specify that the overall goal of teacher education is best conceived as professional identity development (32). Furthermore, professional identity is created during various activities, such as bedside and ambulatory teaching, communication skills training, small group teaching, ward rounds, and exchanges in informal settings (33).

Generic attributes include cultural awareness, ethical awareness, and reflection (3). One of the critical issues in professional identity formation is cultural awareness. Professional frameworks show that different social contracts originate from different countries. The professional identities expected of physicians in these countries are based on these contracts, making self-identity formation dependent on culture and country (17). An important domain in professional identity formation is intersectionality, which considers how gender, race, historical, and cultural factors affect this process. Understanding how various identity experiences influence different medical students is crucial for improving health care delivery. Few studies have explored intersectionality and professional identity formation, and most professional identity research has been silent about how race, culture, or ethnicity influence this process (18). In Eastern countries like Iran, aspects such as hierarchies, communication with patients, teamwork, patient-centeredness, and informed consent differ from those in Western countries. However, the Persian translation revealed that it is a valid and reliable tool in all subscales based on Iranian culture.

The effectiveness of reflection is reinforced when supported by a mentor or conducted as a team activity (7). Reflection is a critical component of professional identity formation and development (34). Additionally, family members, friends, home environments, and other outside influences provide a basis for the professional identity formation process. These factors can either support the commitment essential to becoming a medical professional or inhibit it. Such external influences have become increasingly important as recent generations of students and physicians seek to balance their commitment to medicine with personal well-being and lifestyle (7).

Haruta et al. validated the PSIQ in clinical settings in Japan, demonstrating its validity, which aligns with our findings. Our study also showed that the questionnaire's three factors and all its questions had high Cronbach's alpha coefficient values (35).

A strength of this study is the high response rate from a stratified sample. Another strength is that the integration of medical education and the healthcare delivery system in Iran provides a unique opportunity for using healthcare fields to teach medical students. These fields, especially in rural areas, may improve professional identity formation (36, 37).

However, there are several limitations to this study. First, the research was conducted at a single medical school, so generalizability is limited. Second, the study sample only included medical students, who may not represent other health science students. Third, response bias might occur due to the nature of self-reports.

Given these limitations, additional data collection is essential for using this questionnaire in other health professions. Different study designs, such as random sampling, are recommended to increase generalizability and representativeness. Future studies should focus more on the factors affecting the formation of professional identity in health professional learners.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study revealed that the Persian version of the PSIQ is a valid and reliable tool for measuring the professional self-identity of medical students in Iran. Our findings suggest that similar validation studies should be conducted in other countries, as the construct of professional identity is likely influenced by local cultural determinants.