1. Background

The improvement of patient care quality and clinical outcomes remains a top responsibility and priority for healthcare organizations (1, 2). High-quality care is essential during pregnancy and childbirth, as well as in the postpartum period. The quality of care received by a pregnant woman during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period affects her and her child’s health (3). The quality of care delivered to mothers and infants is reflected by the performance of antenatal care providers and the timeliness and appropriateness of care, ultimately leading to favorable maternal and neonatal outcomes (4). Improving maternal and neonatal healthcare quality is essential for ensuring desirable health outcomes and preventing mortality in mothers and infants (5, 6). The measurement of healthcare quality is one of the first steps towards improving the quality of maternal and neonatal care (7).

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in Britain and Ireland recommends using a maternity dashboard to improve clinical care and continuously monitor clinical outcomes in pregnant mothers. The maternity dashboard helps measure and manage poor clinical performance (8). A maternity dashboard is valuable for the accurate and continuous monitoring of performance, introducing necessary changes in services, and improving patient management (9). A maternity dashboard aims to ensure the implementation and maintenance of clinical governance principles in the daily performance of healthcare providers (8).

Clinical governance is a framework through which healthcare organizations are expected to continuously improve the quality of care and achieve high-quality patient care while maintaining high standards of care. The maternity dashboard helps implement clinical governance principles and identify areas that need attention and actions to improve the patient's safety and satisfaction (9). The maternity dashboard is crucial for making changes to improve the hospital healthcare system’s performance and serves as an efficient tool for assessing the gap between the true performance and expected goals; therefore, it can help managers make informed and desirable decisions (1). The maternity dashboard provides a monthly overview of the performance of gynecology and obstetrics wards respective to prespecified key performance indicators (KPI) (10, 11). One of the features of this dashboard is that it graphically displays deviations in performance and quality indicators using a red-amber-green coding system to alert users about deviations, thus facilitating obtaining an overall perspective on performance and quality of services (9, 12).

Therefore, the maternity dashboard is a dynamic and valuable tool for performance monitoring, continuous improvement of care, and quality assurance (8, 9). Using KPIs aligned with goals is a key step for the successful implementation of such a dashboard (1, 13). In other words, one of the requirements for designing and implementing maternity dashboards is to determine KPIs, which are essential for measuring organizational performance (1, 14). In fact, KPIs are the basis and foundation of a dashboard’s operational structure (13, 15).

The determination of KPIs in a dashboard allows for measuring the quality of the care and services provided (16). Key performance indicators have a significant role in the process of measuring performance by helping in the identification and assessment of performance levels. These indicators help recognize and compare the level of performance between similar services. The ultimate goal of identifying KPIs is to assist in delivering high-quality, safe, and effective care services tailored to the needs of users (17).

The KPIs related to pregnancy care help improve the quality of childbirth services by creating baseline data for monitoring and evaluating fluctuations in performance. These indicators belong to three general thematic dimensions: Antenatal period, childbirth and delivery, and childbirth outcomes, which should have relevance, specificity, measurability, accessibility, objectivity, and timeliness. Evaluating and monitoring performance based on KPIs against predetermined goals or standards forms the cornerstone of good and effective clinical performance (1, 18).

2. Objectives

Performance can be determined using dashboards by offering useful and practical information in the form of KPIs (13, 14, 19). In this regard, a set of KPIs or clinical outcomes can be used to measure the quality of pregnancy care services and the success of maternity dashboards (10, 20). Accordingly, this study aims to investigate and identify the effective KPIs of maternity dashboards.

3. Methods

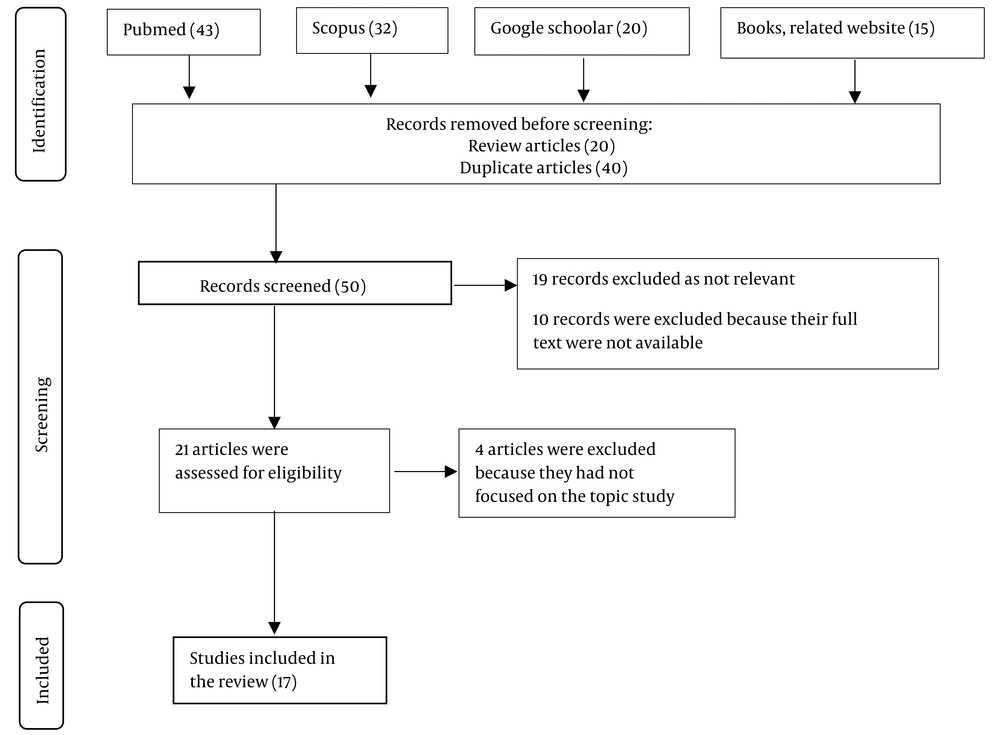

This qualitative applied research was conducted in two stages in 2023 to identify the effective KPIs of the maternity dashboard in Iran. The keywords used in the literature search to retrieve related articles were as follows: Maternity dashboard, clinical dashboards, key performance indicators, clinical care, and quality indicators (Table 1). Relevant articles were searched in databases like PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, as well as in related books and websites. The records were screened for relevance to the topic of the study, which led to the exclusion of a number of studies that were irrelevant to the topic or their full text was unavailable. The remaining full-text articles were assessed for eligibility.

| Databases | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (("maternity dashboard" OR "maternal dashboard" OR "obstetric dashboard") AND ("key performance indicator" OR KPI) AND ("quality indicators" OR "quality measures" OR "clinical quality indicators") AND ("clinical dashboard" OR "healthcare dashboard")) [TIAB] ``` |

| Google Scholar | "maternity dashboard" OR "key performance indicator" OR "quality indicators" OR "clinical dashboard" |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(("maternity dashboard" OR "maternal dashboard" OR "obstetric dashboard") AND ("key performance indicator" OR KPI) AND ("quality indicators" OR "quality measures" OR "clinical quality indicators") AND ("clinical dashboard" OR "healthcare dashboard")) |

In the first stage, a comprehensive literature review was conducted on maternity dashboards and KPIs reported in various sources, and a qualitative comparative analysis was conducted on maternity dashboards in Britain, Australia, Oman, Canada, Brazil, and France. The reason for choosing these countries was full access to their maternity dashboard information. The entry criteria for articles in this stage were:

• Articles in English

• Articles on maternity dashboards

• Articles assessing KPIs and the performance of maternity dashboards

The exclusion criterion in this study was:

• Reporting insufficient details about the KPIs of maternity dashboards

Subsequently, two authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the articles obtained and removed any articles that did not meet the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Both authors contributed their evaluations.

After selecting the articles that met inclusion criteria, KPIs were recorded into a data extraction form. The data extraction form included two main parameters: Indicator classification and KPIs. Then, the data were analyzed according to the study’s objectives.

In the second step of the study, 48 KPIs that were identified for the maternity dashboard in the first step were classified into six categories: Clinical activity, antenatal care, childbirth, maternal complications, fetal and neonatal complications, and postnatal care.

The KPIs were validated using the Delphi technique following 2 steps. For this purpose, a researcher-made questionnaire containing 48 questions based on KPIs was designed to obtain expert opinions. The respondents were given two options of “agree” and “disagree” for each question and a blank space to express their reasons or provide their opinions and suggestions. The validity of the questionnaire was assessed by content validity analysis and based on expert opinions on the research topic. The reliability of the tool was assessed through test-retest, and its correlation coefficient was calculated at 92%.

Next, 30 experts, including 15 gynecologists and 15 health information management specialists, reviewed the questionnaire. All of them were faculty members at the Shahid Beheshti, Iran, and Tehran Universities of Medical Sciences and had at least five years of experience in working and teaching in the research field. After implementing the first phase of the Delphi technique, KPIs with a 100% agreement coefficient were approved. Also, KPIs with an agreement coefficient below 85%, as well as the corrections and suggestions provided in the first stage of the Delphi technique, entered the second phase, in which the KPIs of the maternity dashboard were finalized by an expert panel of 6 gynecologists and 6 health information management specialists.

The data analysis process involved utilizing MAXQDA, software for conventional content analysis, and employing descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) generated in SPSS.

Ethical considerations in this study included obtaining written informed consent, the voluntary participation of experts, the confidentiality of the information obtained, the permission to exit from the study at any stage, and coordinating the time and place of the interview according to the will of the respondent to complete the questionnaire and confirm the indicators.

4. Results

4.1. The Findings of the Literature Review and Comparative Analysis

The 110 articles retrieved were thoroughly reviewed and evaluated by the research team, resulting in the selection of 17 full-text English articles focusing on maternity dashboards’ KPIs. Figure 1 illustrates the flow of information through different phases of the review process. These articles were studied precisely and served as the main sources for collecting research data.

The authors identified the following KPIs and classified them into six groups:

• Clinical activity

• Antenatal care

• Childbirth

• Maternal complications

• Fetal and neonatal complications

• Postnatal care

Table 2 shows the results of the comparative analysis.

| Components/Countries and Categories | Description of KPIs | |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Definition | |

| Australia | ||

| Activity | The total number of infants delivered; The number of females who have given birth | An indicator for the number of babies born and the number of women who have given birth |

| Antenatal care | The first visit before week 12th of pregnancy; Severe fetal growth restriction; Smoking cessation; Pertussis vaccination; Influenza vaccination | An indicator related to access to and use of healthcare services during pregnancy |

| Childbirth | All births – inductions; All births – cesarean section; All births – third- and fourth-degree tears; All births - episiotomy; Standard primiparae – induction rate; Planned vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC); Successful VBAC after planned VBAC; Cesarean section – Robson group 1; Cesarean section – modified Robson group 2; Cesarean section – Robson group 1 & modified 2; Cesarean section – under general anesthesia; Severe perineal tear of third or fourth degree during the first childbirth and its recurrence during subsequent deliveries; Primiparae– perineal tear of the third or fourth degree– (unassisted birth); Primiparae– perineal tear of the third or fourth degree (assisted birth); Primiparae –episiotomy (unassisted birth); Primiparae–episiotomy (assisted birth) | Data on the type of delivery, the rate of natural vaginal delivery, cesarean section, and medical interventions |

| Maternal complications | Blood transfusion during birth admission with a blood loss >499 mL; Blood loss >499 mL (vaginal) and >749 mL (cesarean section); Peripartum hysterectomy | The number of women who bleed during and after delivery and the number of women who underwent hysterectomy during or within 24 hours after delivery |

| Fetal and neonatal complications | Five-minute Apgar score <7; Admission to the special care nursery (SCN)/neonatal intensive care unit (NICU); Perinatal deaths & gestation standardized perinatal mortality ratio (GSPMR) at >32 weeks; | Full-term babies without congenital anomalies who have an Apgar score of less than 7 and need additional care or have higher perinatal mortality |

| Postnatal care | Full-term babies–breastfeeding initiation; Full-term breastfed babies–given formula; Full-term breastfed babies–the most recent breastfeeding; Referral to domiciliary (DOM) or hospital in the home (HITH) | Data on breastfeeding initiation, feeding with formulas, and postnatal care |

| Britain | ||

| Clinical activity | Births; Bookings; Instrumental delivery; Cesarean section | The number of monthly prenatal visits, the number of deliveries, the percentage of cesarean sections, and instrumental vaginal delivery |

| Workforce | Weekly hours of consultation in the maternity ward; Midwifery staff; Midwife-to-birth ratio; Supervisor-to-midwife ratio; Training | The number of hours per week that a consultant is accessible and provides consultation to mothers admitted to the maternity ward, midwifery staff, the ratio of midwives to the number of deliveries, the ratio of supervisors to the number of midwives they are responsible for supervising and training. |

| Clinical outcomes | The clinical outcomes assessed in this study included; Eclampsia; ICU admissions; Need for blood transfusion; Postpartum hysterectomy; Postpartum hemorrhage; Neonatal outcomes (meconium aspiration, hypoxic encephalopathy, birth traumas, neonatal mortality, low Apgar scores, ill babies on SCBU); Risk management (number of SUIs, incident reporting, failed instrumental delivery, massive PPH >21, shoulder dystocia, third/fourth-degree perineal tears); Patient complaints | This indicator includes maternal complications, neonatal complications and deaths, and risk management. |

| Responsive care | Complaints; Attitudes; Clinical care; Organizations; Commendations | Patient complaints and user feedback on maternity services (prenatal clinic, maternity ward, antenatal and postnatal wards) |

| Canada | ||

| Inadequacy of sample volume for newborn screening tests | The proportion of inadequate samples for newborn screening testing | The percentage of newborns’ samples that do not meet the required standards respective to the total number of samples sent from a hospital or midwifery clinic. |

| Episiotomy | Rate of episiotomy in women having a spontaneous vaginal birth | The percentage of women who had a spontaneous vaginal birth and received an episiotomy out of the total number of women who had a spontaneous vaginal birth. |

| Formula supplementation | The proportion of full-term infants who were given formula supplementation at the time of discharge despite being breastfed as well. | The proportion of full-term infants who were given formulas instead of breast milk out of the total number of full-term infants whose mothers had planned to breastfeed them. |

| Elective repeat cesarean delivery prior to week 39th of gestation | The percentage of low-risk women with a history of cesarean section who had prior cesarean delivery at full-term before the 39th week of pregnancy | The percentage of low-risk women who had a repeat cesarean section and underwent the procedure between 37 and 39 weeks of gestation. |

| GBS screening | The percentage of women who gave birth at full-term and underwent screening for Group B Streptococcus infections between the 35th and 37th weeks of pregnancy. | The proportion of women who had an unscheduled cesarean delivery and were screened for Group B Streptococcus infections between the 35th and 37th weeks of pregnancy, out of the total number of women who gave birth at full term. |

| Postdate induction prior to week 41st of gestation | The percentage of women who underwent induction of labor due to post-term pregnancy and delivered before completing 41 weeks of gestation. | The proportion of women who underwent induced labor and delivered before the week 41st of gestation out of the total number of women who had induced labor. |

| Brazil | ||

| Maternity production indicators | Total number of women hospitalized; Total number of births; Total number of high-risk women; The overall number of females who are younger than 15 years old.; The overall number of females aged between 15 and 35 years old; The overall number of females who are older than 35 years old. | The total number of hospitalized women, deliveries, and high-risk women |

| Government contracted indicators | Admission types and cesarean sections in high-risk pregnant women; Length of stay (LOS) | Indicators that have been contracted by the government comprise the proportion of women with high-risk pregnancies, which is calculated by dividing the total number of patients admitted during a given period, as well as the duration of hospitalization. |

| Delivery indicators: Vaginal deliveries and cesarean sections | Cesarean section rate; LOS, in general, births; LOS in vaginal deliveries; LOS in cesarean section | An indicator related to vaginal delivery and cesarean section |

| Perinatal indicators | The rate of the five-minute Apgar score below 7; Apgar score after the fifth minute below 7 (adjusted); Breastfeeding in the first hour after birth; Breastfeeding in the first hour after birth (adjusted) | An indicator related to the perinatal period, the rate of low Apgar score at the fifth minute, and live infants fed in the first hour of life |

| Care quality indicators by professional profile | Maternal DSP (being discharged from the hospital, being transferred to another medical facility, leaving the hospital against medical advice, or experiencing maternal death); Neonatal DSP (being discharged from the hospital, being transferred to another medical facility, leaving the hospital against medical advice, experiencing fetal death before or during admission, neonatal death, or being retained in the hospital for further treatment) | Care quality indicators |

| France | ||

| Management of pregnancy and labor | Measurement of nuchal translucency (NT) in the first trimester of pregnancy ; Screening for three markers during the first trimester of pregnancy ; Vaginal sampling in the ninth month of pregnancy to test for group B streptococcus; Use of epidural analgesia ; Cesarean section performed before the onset of labor ; Cesarean section performed during labor ; Full-thickness tears (third/fourth-degree perineal tear) ; Uterine rupture ; Intact perineum (undamaged perineal area) ; Hospital-acquired infections at the surgical site ; Blood transfusion during or after delivery ; Transfer or admission of the mother to the intensive care unit (ICU); The decision to breastfeed at discharge | Pregnant women population management from pregnancy to postpartum |

| Management of low-risk women | Performing a cesarean delivery for low-risk women before the onset of labor; Performing a cesarean delivery for low-risk women during the process of labor | Management of low-risk pregnancies |

| Management of newborns | Vaginal delivery with the use of an instrument; The proportion of neonates who weigh more than the low-birth-weight threshold and require admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU); Birth after thirty-seven weeks with a five-minute Apgar score of <7 | Management of newborns |

| Oman | ||

| Clinical activity | Deliveries; Admission to the antenatal ward (excluding direct admissions to the delivery room); Outpatient department appointment; Instrumental deliveries; Cesarean section rate | The number of prenatal visits, admission to the maternity ward, the number of deliveries, and the percentage of cesarean sections and instrumental delivery |

| Maternal measures | Induction of labor; Workforce; Midwife/patient ratio; Supervisor/midwife ratio; Eclampsia; Intensive care unit admission; Severe postpartum hemorrhage; Third-degree perineal tear; Shoulder dystocia; Hematomas; Postpartum hysterectomy; Others (e.g., near miss/mortality) | The number of staff, the ratio of midwives to patients, the ratio of consultants to midwives, and maternal complications |

| Neonatal outcomes | Low five-minute Apgar score (<7); Perinatal asphyxia; Meconium aspiration syndrome; Stillbirth; Stillbirth with diabetes; Early neonatal death | This indicator includes neonatal outcomes, complications, and mortality. |

| Patient complaints | Complaints | Patient complaints and feedback |

4.2. The Findings of the Initial Phase of the Delphi Method

The findings of the initial phase of the Delphi method showed that all experts (100%) agreed upon 3 main categories of KPIs as follows and confirmed the subgroups.

• Clinical activity

• Fetal and neonatal complications

• Postnatal care

Three indicators related to antenatal care (i.e., the first visit before 12 weeks of gestation, NT measurement in the first trimester of pregnancy, and vaginal sampling during the ninth month of pregnancy for Group B streptococcus, GBS, screening) were accepted by less than 40% of the experts. Furthermore, the experts suggested a number of other indicators to be added to this category (Table 3). The indicators related to childbirth and maternal complications are shown in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

| Antenatal Indicators | Agreement Percentage | Suggestions |

|---|---|---|

| First visit before 12 weeks | 30 | Addition of the following: Mother’s age, the exact date of the last menstrual period (LMP), first pregnancy, abortion rate, infertility rate, type of infertility, infertility treatment methods, maternal diseases, number of previous births, type of previous births, effects of previous births |

| First trimester screenings | 100 | Pregnancy screenings |

| NT measurement in the first trimester of pregnancy | 20 | Follow-ups during pregnancy (sonography), follow-ups during pregnancy (laboratory tests), follow-up methods, complications of negative points in sonography, laboratory tests, screenings during pregnancy, treatment of complications of negative points in sonography, laboratory tests, and screenings |

| Severe fetal growth restriction | 100 | - |

| Smoking cessation | 100 | - |

| Vaginal sampling in the ninth month for GBS screening | 20 | - |

| Injection of the Tdap triple vaccine | 100 | - |

| Injection of the influenza vaccine | 100 | - |

| Birth Indicators | Agreement Percentage | Suggestions |

|---|---|---|

| Births - Induction of labor | 100 | - |

| Natural vaginal delivery | 80 | The type of natural delivery and relevant patient satisfaction rate |

| Cesarean section | 80 | The type of cesarean section and relevant patient satisfaction rate |

| All deliveries – episiotomy | 100 | - |

| Primiparae cesarean section | 100 | - |

| Cesarean section under general anesthesia | 100 | - |

| VBAC | 100 | - |

| Primiparae, episiotomy | 100 | - |

| Maternal Complications Indicators | Agreement Percentage | Suggestions |

|---|---|---|

| The volume of bleeding during vaginal delivery and cesarean section | 100 | - |

| Hysterectomy during delivery | 90 | - |

| Postpartum hysterectomy | 90 | - |

| Eclampsia | 90 | - |

| Transfer or admission to the ICU | 100 | - |

| Uterine rupture | 100 | - |

| Third- and fourth-degree perineal tear (the first delivery) | 100 | - |

| The first delivery, third- and fourth-degree perineal tear (unassisted delivery) | 100 | - |

| The first delivery, third- and fourth-degree perineal tear (assisted delivery) | 100 | - |

| Third- and fourth-degree perineal tear (subsequent delivery) | 100 | - |

| Postpartum bleeding | 100 | - |

| Maternal complications following shoulder dystocia | 90 | - |

| Nosocomial infections at the surgical site | 100 | - |

| Need for blood transfusion during or after delivery | 100 | - |

| Death | 100 | Incorporation of complications during the puerperium period into maternal complication indicators |

4.3. The Findings of the Second Step of the Delphi Technique

In the second step of the Delphi technique, essential KPIs required for designing a successful maternity dashboard were finalized by an expert panel after carefully reviewing the indicators (Table 6).

| Number | KPI Categories | KPI Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clinical activity | Number of monthly prenatal visits; Number of women with high-risk pregnancies; Number of admissions to the maternity ward; Number of births; Number of babies born |

| 2 | Antenatal | Mother’s age; The exact date of LMP; Date of the first pregnancy; Abortion rate; Infertility rate; Type of infertility; Infertility treatment methods; Maternal diseases; Number of previous births; Type of previous births; Outcomes of previous births; Prenatal screenings; Follow-ups during pregnancy (sonography); Follow-ups during pregnancy (laboratory tests); Follow-up methods; Complications of negative points in sonography, laboratory tests, and screenings during pregnancy; Treatment of complications of negative points in sonography tests and screening; Severe fetal growth restriction; Smoking cessation; Tdap triple vaccination; Influenza vaccination |

| 3 | Birth | Births - Induction of labor; Natural vaginal delivery; Satisfaction with natural delivery; Cesarean section; Satisfaction with cesarean section; All deliveries – episiotomy; Primiparae cesarean section; Cesarean section under general anesthesia; VBAC; Primiparae, episiotomy |

| 4 | Maternal complications | The volume of bleeding during vaginal delivery and cesarean section; Hysterectomy during childbirth; Postpartum hysterectomy; Eclampsia; Transfer or admission to the ICU; Uterine rupture; Third- and fourth-degree perineal tear (the first birth); First delivery, third- and fourth-degree perineal tear (unassisted delivery); First delivery, third- and fourth-degree perineal tear (assisted delivery); Third- and fourth-degree perineal tear (after birth); Postpartum bleeding; Maternal complications following shoulder dystocia; Nosocomial infection at the surgical site; Need for blood transfusion during or after delivery; Maternal complications during the puerperium period; Mortality rate |

| 5 | Fetal and neonatal complications | Perinatal mortality rate; Meconium aspiration syndrome; Hypoxic encephalopathy; Birth-related traumas; Shoulder dystocia; Low Apgar score; Number of ill babies in the neonatal intensive care unit (SCBU); Perinatal asphyxia |

| 6 | Postnatal | Breastfeeding initiation time; Normal babies fed with breast milk/formulas; Discharge from the hospital or transfer to another hospital; Neonatal care |

5. Discussion

Dashboards are useful tools to monitor the performance and quality of supportive healthcare organizations by providing accurate, timely, and vital information (21). Maternity dashboards enable clinical teams in maternity wards to compare their performance against predetermined standards and goals for clinical quality improvement (22). Some studies have examined the role of maternity dashboards in improving patient care, recommending the use of maternity dashboards as a tool for improving clinical care, accurate and continuous monitoring of performance, and making amendments to achieve better performance (1, 8-10).

When designing a dashboard, effective tools should be used to provide relevant and timely information in a meaningful, concise, and usable manner on a single sheet of paper (23, 24). A crucial step for designing any dashboard and enhancing organizational performance involves identifying vital KPIs (25) as a part of the performance monitoring process according to national standards. Dashboards have been recognized as a tool for achieving safe and high-quality healthcare and ensuring continuous quality improvement (17). Accordingly, this study aimed to identify the KPIs of maternity dashboards in Iran.

As mentioned, the identification of KPIs is necessary for improving performance and providing high-quality care (26). In this study, experts agreed unanimously on a set of KPIs that were presumed necessary to monitor the performance of hospital wards engaged with providing antenatal, childbirth, and postnatal pregnancy care. Based on the results of this study, the KPIs associated with maternity dashboards were divided into six groups, including clinical activity, antenatal care, childbirth, maternal complications, fetal and neonatal complications, and postnatal care.

Clinical activity is one of the important KPIs that should be regularly monitored in a maternity ward. This indicator can include parameters such as the number of monthly prenatal visits, the number of admissions to the maternity ward, and the number of deliveries. For example, the number of admissions to the maternity ward should be monitored to predict and prevent shortages in the number of available hospital beds in the case of an overflow of patients or insufficient staff, which would increase patient dissatisfaction and jeopardize patient safety (27). In the studied countries, for example, in Australia, the activity indicator reflected the total number of infants delivered and the number of mothers who gave birth to them. In Britain, this indicator referred to the number of monthly prenatal visits and deliveries (11, 28, 29). In the current study, clinical activity included the number of monthly prenatal visits, the number of women with high-risk pregnancies, the number of admissions to the maternity ward, the number of deliveries, and the number of babies born.

Antenatal care is essential for preventing adverse outcomes during pregnancy and childbirth. The antenatal indicator examines various healthcare functions and measures the quality of the healthcare received during pregnancy (30, 31). In the studied countries, antenatal indicators included the first visit during pregnancy, severe fetal growth restriction, smoking cessation, vaccination history, laboratory test results, screening procedures, and sonography in each trimester of pregnancy (1, 29, 32, 33). In this study, essential antenatal indicators were selected and approved by experts, including maternal age, the exact date of LMP, date of the first pregnancy, history of abortion, infertility rate, type of infertility, infertility treatments received, maternal comorbidities, the number and type of previous deliveries, outcomes of previous deliveries, undergoing pregnancy screening tests, follow-up procedures (sonography, laboratory tests) during pregnancy, follow-up methods, adverse effects of sonography, laboratory tests, and other screening tests during pregnancy and their management, severe fetal growth restriction, smoking cessation, triple Tdap vaccination, and vaccination for influenza.

Birth indicators evaluate the types of delivery, the percentage of natural vaginal deliveries and cesarean sections, and the rate of medical interventions (32, 34). The selected birth indicators included birth-induction labor, natural vaginal delivery, satisfaction with vaginal delivery, the rate of cesarean section, satisfaction with cesarean section, all births-episiotomy, first-time cesarean section, undergoing general anesthesia before cesarean section, planned vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC), first-time delivery, and episiotomy.

Childbirth is always stressful for the mother and causes complications for both the mother and the newborn, necessitating emergency care (35). Regarding the maternity dashboards developed in the countries studied in this research, postpartum maternal complications included hemorrhage, hysterectomy, eclampsia, perineal rupture, uterine rupture, infections, and death, and neonatal complications included low Apgar scores, hypoxic encephalopathy, traumas, and death (1, 10, 32). In this study, maternal complications included the volume of bleeding following vaginal delivery and cesarean section, hysterectomy during delivery, postpartum hysterectomy, eclampsia, admission to the ICU, uterine rupture, grade III or IV perineal rupture, postpartum hemorrhage, complications related to shoulder dystocia, infections at the surgery site, the need for blood transfusion during or after delivery, postpartum complications, and death. Also, neonatal complications included perinatal mortality, the newborn’s respiratory distress due to the presence of meconium, hypoxic encephalopathy, birth traumas, shoulder dystocia, low Apgar scores, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and perinatal asphyxia.

Postnatal indicators reflect the quality of postnatal care (36). In this study, this indicator included the time of breastfeeding initiation, the number of healthy neonates fed with breast milk/formula, discharge from the hospital or being transferred to another hospital, and neonatal care.

5.1. Conclusions

The present study aimed to determine the KPIs required for developing a maternity dashboard in Iran. The results demonstrated that maternity dashboards could provide valuable and practical information through well-defined KPIs, serving as performance assessment criteria. These KPIs enable managers to make timely and appropriate decisions, ensuring the provision of safe and high-quality prenatal care, preventing adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes, and promoting overall health in maternity wards. As such, KPIs are essential tools for the successful design and implementation of maternity dashboards.