1. Background

Marriage holds a special position in different cultures and communities as it plays a crucial part in forming families and providing a safe and desirable condition for meeting human’s intrinsic needs, such as reproduction, emotional support, regulation of sexual behavior, and a resultant psychological and physical health (1-3). However, global evidence shows a trend of lower marriage rates and higher divorce rates within 1960 to 2022. The marriage rates in 1960 and 2022 were 8.06 and 4.86 per 1,000 individuals, respectively; however, the divorce rates were 1.01 and 2.03 in the same period (4).

In the US, approximately half of the first-time marriages end in divorce, including 33% in the first 10 years (5). In Iran, the rate of marriage has increased from 6.2 in 2020 to 6.7 in 2022 per 1,000 population; however, the rate of divorce has also increased from 2.1 to 2.5 per 1,000 population in the same period (6). The above-mentioned transitional pattern in divorce to marriage ratio is attributed to the rapid and extensive changes of societies in various aspects, such as urbanization and modernity, which have inevitably changed individuals’ lifestyles and expectations (7-10). One study reported that cultural changes have occurred in Iran, compared to two decades ago, from traditional and religious values to non-traditional and modern values in mate selection (11). The evidence shows that by increasing marital satisfaction (MS) and longevity, lowering the rate of divorce is possible.

According to the dyadic adjustment scale (DAS), dyadic satisfaction is dependent on the agreement between partners, contentment, and commitment in the relationship, expression of affection and sex, and common interests and activities by the couple (12). Marital satisfaction is also defined as the attitude that an individual has toward his or her marital relationship. One view suggests a general decline in MS over time (13). Another study suggests a decline in MS in the early stages with a gradual increase later (14). Still, other studies indicate no significant change in MS (15, 16). The evidence shows that MS is related to children, the communication skills of couples, and their ethnicity and level of income (8, 17).

2. Objectives

Considering the above-mentioned statements and due to the pivotal role MS and its associated factors have in family consistency and integration, this study aimed to address these issues.

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Study Setting

As a prospective cohort study and by a convenient method of sampling, 495 married women who passed up to 2 years of their marriage were enrolled in this study. All of these women had been referred by official marriage registration offices for attendance in the marriage preparedness courses, which were run by Shiraz Medical University affiliated with Bahar-E-Neku Institute in June 2019 in Shiraz, Iran. These courses are obligatory sessions for 6-hour and should be passed by each couple before getting legal permission for the marriage. At first (in 2019), researchers of this study attended the above-mentioned sessions and asked all participants to fill out the questionnaires. Then, after about 2 years of marriage and living together, they were contacted by phone and asked again to fill out the second questionnaire, which was sent to them through WhatsApp channel. A trained fellow citizen female psychologist called the participants in this stage. The 2nd stage of the study was concordance with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic; therefore, it was obligatory to conduct the survey virtually. No exclusion criterion was applied except non-willingness to participate in this study. Of note, the STROBE cohort reporting guidelines were used in this article (18).

3.2. Questionnaire

The researcher-made questionnaire, which was used in the 1st stage of this study, consisted of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (39 items) and criteria for mate selection (21 items). In the 2nd stage, the questionnaire included updated demographic and socioeconomic information and queries about MS, fulfillment of mutual expectations, and life transition experienced events, such as childbearing, support of mutual families, and perception about the degree of correctness of what they had regarded as mate selection criteria at the beginning of a marriage.

The content and face validity of both stages' questionnaires were achieved by merging the findings of a deep literature review with frequent expert opinion panels, which consisted of judicial family counselors, psychologists, psychiatrists, sociologists, and community medicine specialists. Face validity was also confirmed by these panels. The reliability of the questionnaire in the 1st and 2nd stages was 70.6% and 88.6% by Cronbach's alpha, respectively. The importance of mate selection criteria was scored by a 6-point Likert scale from very high to nil. Furthermore, the level of self-reported MS was tailored by a 1 to 10 scale, which subsequently ≤ 5 and > 5 points were considered the low and high levels of satisfaction, respectively. Additionally, we can mention other sources of MS questionnaires, both from Iranian and non-Iranian studies, to further support the validity and reliability of the current methodology. Examples of such questionnaires include the widely used Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale, the ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale, and others mentioned in references (19-23).

3.3. Data Analysis

After quality-checking the data, SPSS software version 25 was used for statistical analysis. Firstly, univariate analysis was performed by the t-test and chi-square test; then, variables with a P-value ≤ 0.2 were included in the binary logistic regression test (Backward LR method). A P-value < 20.05 was considered significant in the final analysis.

3.4. Ethics

The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS), Shiraz, Iran (No.: IR.SUMS.REC.1399.1074). Furthermore, Helsinki's ethical principles for medical research were considered in this study. It should be mentioned that all interviewees were provided with sufficient information about the purpose and process of the research and their rights; however, written consent forms and verbal consent about participation in this study were obtained at the 1st and 2nd stages of this study, respectively.

4. Results

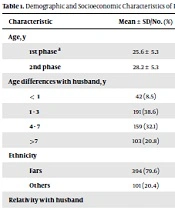

Out of 562 participants in the 1st stage, 495 answered the questionnaire in the 2nd stage of this study, showing an 88% response rate. The mean time of follow-up till this stage of the study was 23.8 ± 8 months. The mean age of the participants and their husbands was 28.2 ± 5.3 and 32.1 ± 4.6 years old, respectively; nevertheless, mostly 350 (70.7%) had 1 - 7 years age-difference with their husbands, 388 (78.4%) were educated for more than 12 years, 364 (73.5%) did not have relativity with their husbands, 369 (74.5%) did not have children, 334 (67.5%) were not employed, and 432 (87.3%) did not live with their parents after marriage. Furthermore, 130 cases (26.3%) co-lived with individuals other than their husbands in the same house (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD/No. (%) | Characteristic | Mean ± SD/No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | Way of knowing husband before marriage | ||

| 1st phase a | 25.6 ± 5.3 | By others' recommendations | 323 (65.3) |

| 2nd phase | 28.2 ± 5.3 | by herself | 172 (34.7) |

| Age differences with husband, y | The interval between becoming familiar with husband and marriage, mo | 23 ± 24.8 | |

| < 1 | 42 (8.5) | The interval between legal marriage and wedding, mo | 6.3 ± 7.7 |

| 1 - 3 | 191 (38.6) | The interval between wedding and participation in this study, mo | 23.8 ± 8.3 |

| 4 - 7 | 159 (32.1) | Leaving with her family after marriage | |

| >7 | 103 (20.8) | Yes | 63 (12.7) |

| Ethnicity | No | 432 (87.3) | |

| Fars | 394 (79.6) | Leaving with husband’s family after marriage | |

| Others | 101 (20.4) | Yes | 124 (25.1) |

| Relativity with husband | No | 371 (74.9) | |

| Yes | 131 (26.5) | Co-living with others (other than husband) after marriage in the same house | |

| No | 364 (73.5) | Yes | 130 (26.3) |

| Having children | No | 365 (73.7) | |

| Yes | 126 (25.5) | Others were supported financially by their husbands after marriage | |

| No | 369 (74.5) | Yes | 67 (13.5) |

| Education, y | No | 428 (86.5) | |

| 1st phase | 1st degree family dimension | ||

| < 12 | 142 (28.7) | ≤ 4 | 36 (7.3) |

| > 12 | 351 (70.9) | > 4 | 457 (92.3) |

| 2nd phase | Job status (first phase) | ||

| < 12 | 97 (19.6) | Having a job | 184 (37.2) |

| > 12 | 388 (78.4) | Jobless | 311 (62.8) |

| Job status (second phase) | |||

| Having a job | 161 (32.5) | ||

| Jobless | 334 (67.5) |

Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics of Participants (n = 495)

Marital satisfaction was high and low in 442 (89.3%) and 53 (10.7%) subjects, respectively. The mood of the husband (485; 98%) among personal factors, the temperament of the husband’s family (414; 83.6%) among sociocultural factors, and the husband’s financial status (127; 25.7%) among economic characteristics were mentioned as the most important criteria for choosing mate at the marriage time. Overall, 459 subjects (92.7%) claimed that they had complete discretion in choosing their spouses; nevertheless, 14 subjects (2.8%) had been under the compulsion of their family in this regard, and 6 cases (1.2%) did not have any criterion for choosing a spouse (Table 2).

| Criteria | High to Very High | Medium | Low to Very Low | Nil |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal characteristics | ||||

| Similarity in age | 125 (25.3) | 193 (39) | 147 (29.7) | 30 (6.1) |

| Husband’s mood | 485 (98) | 5 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.8) |

| The beauty/handsomeness of the husband | 197 (39.8) | 232 (46.9) | 45 (9.1) | 21 (4.2) |

| The level of readiness of the husband for marriage and accepting the responsibility of living together | 379 (76.6) | 77 (15.6) | 7 (1.4) | 32 (6.5) |

| My level of readiness for marriage and accepting the responsibility of living together | 311 (62.8) | 152 (30.7) | 16 (3.2) | 16 (3.2) |

| Sociocultural characteristics | ||||

| Husband's job types, regardless of income | 183 (37) | 187 (37.8) | 63 (12.7) | 62 (12.5) |

| Educational level of the husband | 206 (41.6) | 166 (33.5) | 76 (15.4) | 47 (9.5) |

| Fame or the social position of the husband | 132 (26.7) | 147 (29.7) | 104 (21) | 112 (22.6) |

| The political position of the husband | 67 (13.5) | 117 (23.6) | 135 (27.3) | 176 (35.6) |

| Religious beliefs of husband | 301 (60.8) | 117 (23.6) | 38 (7.7) | 39 (7.9) |

| Political and social beliefs of husband | 191 (38.6) | 156 (31.5) | 86 (17.4) | 62 (12.5) |

| Husband's place of residence | 171 (34.5) | 114 (23) | 63 (12.7) | 147 (29.7) |

| The temperament of the husband's family | 414 (83.6) | 59 (11.9) | 13 (2.6) | 9 (1.8) |

| Fame or sociopolitical position of the husband's family | 109 (22) | 155 (31.3) | 108 (21.8) | 123 (24.8) |

| Religious beliefs of the husband’s family | 226 (45.7) | 156 (31.5) | 66 (13.3) | 47 (9.5) |

| Political and social beliefs of the husband's family | 106 (21.4) | 176 (35.6) | 120 (24.2) | 93 (18.8) |

| The advice of family members or relatives | 224 (45.3) | 127 (25.7) | 70 (14.1) | 74 (14.9) |

| The advice of my non-family friends | 104 (21) | 156 (31.5) | 140 (28.3) | 95 (19.2) |

| Medical advice or psychological counseling | 96 (19.4) | 104 (21) | 55 (11.1) | 240 (48.5) |

| Economic characteristics | ||||

| Husband's financial or income status | 127 (25.7) | 245 (49.5) | 78 (15.8) | 45 (9.1) |

| The financial situation of the husband's family | 55 (11.1) | 203 (41) | 125 (25.3) | 112 (22.6) |

Role of Criteria in Choosing Husbands by Newly Married Women a

Among all participants, 359 subjects (72.5%) were optimistic about strengthening their life consistency in the next years, compared to 12 subjects (2.4%) who were pessimistic. Furthermore, 32 participants (6.5%) predicted a steady state, and 92 participants (18.6%) had a non-predictable perspective toward their living consistency in the next years. On the other hand, 460 subjects (92.9%) reported that their husbands were highly satisfied with living with them.

Among all subjects, 491 cases (99.1%) stated that education and counseling are necessary for young individuals before marriage, including 316 subjects (63.8%) who believed that the best time for these courses is after 18 years of age or around marriage time, and 175 subjects (35.4%) who mentioned that the best time for education is before 18 years of age. In terms of the best time for education and counseling after marriage, 81 (16.4%), 58 (11.7%), and 38 (7.7%) subjects stated that it should be held in the 1-3 months, 3-12 months, and after 1st year of marriage; however, 104 cases (21%) said that counseling is needed in more than one of the above-mentioned intervals,175 cases (35.4%) believed that it is only necessary in case of facing problems, and 39 cases (7.9%) said that it is not necessary at all.

The best age of marriage for females and males is 25 and 29 years old, respectively, as announced by the participants. In the univariate analysis, living with the husband’s family after marriage, the handsomeness of the husband, the financial situation of the husband's family, discretion in choosing a husband, the trend of her family or her husband’s family support after marriage, and the belief that her criteria of mate selection at the marriage time had been correct were associated significantly with MS. Furthermore, the extent of knowing about each other before and after marriage, marital sexual satisfaction, mutual fulfillment of expectations, husband’s satisfaction, consistency of marital living, frequency of talking with husband about mutual expectations, developing chronic disease or using cigarette, alcohol, substance or psychological drugs by herself or husband after marriage, and attendance in family counseling sessions after marriage were correlated significantly with MS (Appendix 1 in the Supplementary File).

In the regression analysis, the belief that her criteria of mate selection had been correct (OR = 21.4, P < 0.001 ), fulfillment of the husband’s expectations (OR = 13.1, P < 0.001), marital sexual satisfaction (OR = 11.5, P < 0.001), knowing about husband before marriage (OR = 9.4, P < 0.001), not using cigarette, alcohol, substances or psychological drugs after marriage (OR = 8.5, P = 0.001), not living with husband’s family at the same house after marriage (OR = 6.4, P = 0.002), not developing a type of chronic disease in husband after marriage (OR = 5.9, P = 0.002), and increasing trend of husband’s family support after marriage (OR = 5.9, P = 0.001) were the significant correlates of MS. Furthermore, not using cigarettes, alcohol, substances, or psychological drugs by the husband after marriage (OR = 3.6, P = 0.04), knowing the husband before marriage by herself (OR = 3.5, P = 0.03), monthly talking with the husband about mutual expectations (OR = 3.5, P = 0.03), and higher age of husband (OR = 1.1, P = 0.03) were among the main significant determinants of MS in the young married women (Table 3).

| Variables | B | SE | P-Value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | -6.4 | 2.2 | 0.004 | 0.002 | - |

| By your current experiences, to what extent do you think that the criteria you had at the beginning of your marriage for choosing a husband were correct? (Much/Not much) | 3.0 | 0.6 | < 0.001 | 21.4 | 5.9 - 76.9 |

| Up to this stage of your living together, to what extent have you been able to fulfill the expectations of your husband? (Much/Not Much) | 2.5 | 0.6 | < 0.001 | 13.1 | 3.5 - 47.9 |

| Has marital sex been satisfactory for both you and your husband? (Yes/No) | 2.4 | 0.6 | < 0.001 | 11.5 | 3.3 - 39 |

| Considering your current experiences, how much do you think you were able to fully know your husband before marriage? (Much / Not Much) | 2.2 | 0.6 | < 0.001 | 9.4 | 2.8 - 31.4 |

| History of using cigarettes or alcohol or substances or psychological drugs by you after marriage (No/Yes) | 2.1 | 0.6 | 0.001 | 8.5 | 2.3 - 31.2 |

| Living with husband’s family at the same house after marriage (No/Yes) | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.002 | 6.4 | 2.0 - 20.8 |

| Developing a type of chronic disease in husband after marriage (No/Yes) | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.002 | 5.9 | 1.9 - 18.1 |

| How was the trend of your husband’s family regarding supporting your marriage since you got married? (Increasing/Decreasing) | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.001 | 5.9 | 1.9 - 17.6 |

| History of using cigarettes or alcohol or substances or psychological drugs by your husband after marriage (No/Yes) | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.04 | 3.6 | 1.0 - 12.8 |

| How did you become familiar with your husband in the pre-marriage stage? (By myself /By others) | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 3.5 | 1.1 - 11.1 |

| Since the beginning of your marriage, how often did you talk with your husband about mutual goals and expectations? (At least once per month/Once every several months) | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.03 | 3.5 | 1.0 - 11.5 |

| Age of husband | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 1.1 | 1.0 - 1.3 |

| Age | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.2 | 1.0 - 1.4 |

Binary Logistic Regression (Backward LR) of Associated Factors with Marital Satisfaction in Young Married Women

5. Discussion

This study revealed that 9 of 10 newly married women were highly satisfied after 2 years of starting living with their husbands; nevertheless, 1 in 10 was less satisfied. Furthermore, only 7 of 10 women were optimistic about the upward strengthening of their life consistency in the next years. Women purported that among their mate selection criteria, the mood of the husband, the temperament of the husband’s family, and his financial status were mostly important. Regression analysis showed that MS was associated with both pre- and post-marriage factors. Among pre-marriage factors, the age of the husband and the extent and the way of knowing him were more important. Among post-marriage factors, the belief that mate selection criteria had been chosen correctly at the marriage time, fulfillment of the husband’s expectations, marital sexual satisfaction, being a healthy couple, not using cigarettes, alcohol, substances, or psychological drugs by herself or her husband, not living with husband’s family at the same house, increasing trend of husband’s family support, and frequent talking with husband about mutual expectations were the significant determinants of MS.

Available international statistics by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) showed that marriage rates have dropped; nevertheless, the marriage age has grown during the past half-century (24). These trends are also true in Iran, which has been faced with a significant decreasing trend in the marriage rate, especially in the last 5 years (25). One study was conducted to detect the effects of culture and sex on mate selection using 9 474 subjects from 33 countries. The aforementioned study showed that chastity proved to be the mate characteristic on which cultures varied the most. Each culture displayed a unique preference ordering; however, there were some similarities among all cultures. The first dimension of this study was interpreted as traditional versus modern, with China, India, Iran, and Nigeria anchoring one end and the Netherlands, Great Britain, Finland, and Sweden anchoring the other. However, Iran has been observed to have the lowest level of commonalities with an international average, compared to other countries in the Middle East (26).

In terms of mate selection criteria and in line with the results of the present study, some studies concluded that the personality and behavioral traits of the husband and his family are more important; however, opposite to these studies, the appearance, financial status, and religious beliefs of the husband and his family were not considered the important criteria for choosing mate by women who participated in the present study (27-30). Education and training about the criteria for choosing a mate are necessary. However, criteria might change according to interaction and intellectual, emotional, and social growth over time (5).

Marital satisfaction is an important area for researchers and married couples alike. For researchers, understanding the workings of relationships that contribute to higher satisfaction remains a worthy goal. Identifying contributing factors to satisfaction allows married couples and those in marital counseling and marriage education and enrichment to employ strategies that might contribute to a more satisfying marriage and likewise avoid other behaviors that might contribute to a decrease in MS (16).

One survey, which was conducted on 1 457 adult residents of Michigan, showed that almost four-fifths (79%) of married adults were strongly satisfied with their marriages. This level of satisfaction was less than what we observed in the current study, and it might be due to the study on longer-term married couples. However, the aforementioned study (similar to the findings of the current study) revealed that sex and level of education were not associated with MS; however, (in contrast to the present study), it concluded that income (directly), race, and having children (indirectly) were also correlated with MS. The aforementioned study remarked that the majority of married couples were satisfied with their marriages; nevertheless, being satisfied did not imply complete happiness. A small number (8 - 13%) of respondents who were satisfied with their marriage simultaneously felt resentment toward their spouse, and about 4.7% of those who were satisfied sometimes thought of divorcing their husbands. On the other hand, 36% of those who were not satisfied with their marriage sometimes thought about divorcing. The aforementioned study concluded that although most couples felt that their marriages were satisfactory, this did not necessarily mean the high quality of their marriage (31).

A qualitative study on married women in Pakistan remarked 16 categories as associated factors with happy marriage. These factors included similarities in religiosity, satisfaction, compromise, love, care, trust and understanding, communication, age differences, sincerity, respect, sharing, forgiveness, spouse temperament, strength through children, family structure, education and status, and positive in-laws’ relations (32). A study on MS in women in Jordan revealed that their satisfaction was at the medium level, and it was related to the level of their education and family income (in contrast to the present study); however, it was not related to the years of marriage, number of children, and job status of women (in line with the present study) (33).

Another study revealed that MS had a significant relationship with the level of love and interest, the length of married life, the age difference, the socioeconomic base, and the level of education of the couple. These factors were not correlated significantly with MS in the present study. However, similar to the findings of the current study, the aforementioned study remarked that the same level of education of the couple, the amount of family income, and the employment status of married women (employed versus householders) were not correlated with MS. Finally, the results of the multivariable regression showed that the level of love and interest of the couple (as the only remaining significant variable) predicts about 40% of the couple's satisfaction (34).

A study in Tehran, Iran, concluded a main direct association between religiosity and MS of men and women, while such a relationship was not shown in the current study (35). The message of an unstructured, in-depth interview study with the Iranian couples and experts was that for a successful marriage, premarital knowing of each other and families, knowing necessary life skills, and understanding married life are necessary. The aforementioned study highlighted that the couples will acquire the necessary development and flourish to manage married life through providing positive behavioral qualities, including personality liberation (36).

A longitudinal study assessed the effect of demographic, psychological, marital process, gender-related, and life transitional influences on MS and marital conflict for husbands and wives over time. As a result, there is some support for gender-based influences on couples’ MS and conflict. Additionally, there is some support to suggest that wives’ marital and interpersonal functioning might be a greater predictor for husbands’ MS and marital conflict (5).

By using structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques to identify the association between marital characteristics and marital processes with MS, a sample of 201 participants who were in their 1st marriages were studied. Structural equation modeling identified a path model wherein six marital interaction processes had a statistically significant influence on MS when mediated by three latent factors of marital characteristics (love, loyalty, and shared values) and two moderating variables (length of marriage and gender of participant). The pathway of love was associated with communication and the expression of affection. The pathway of loyalty was associated with sexuality/intimacy and the ability to build consensus. Moreover, the pathway of shared values was associated with traditional versus non-traditional marital roles and the ability of the couple to manage conflicts (37).

5.1. Strengths, Limitations, and Recommendations

This study, as the first longitudinal study in Iran, paid attention to a wide spectrum of factors that were related to MS in newly married women. As a limitation, this study was conducted only on women, and if it could be extended to their husbands, the results could be compared mutually. Logistic shortages and difficulties in accessibility to men in the studied region during the COVID-19 epidemic caused this limitation. The authors aim to continue this study in the next years to trace and have a more comprehensive outlook on the trend of MS and its correlates and the intention to divorce that might happen among couples.

5.2. Conclusions

In the present study, it was shown that MS was directly related to the pre-marriage factors and post-marriage factors. These findings clarify the importance of including these items in the education and training of couples and even their parents before and after marriage about these determinant factors.