1. Background

The World Health Organization has identified family planning (FP) as one of the six fundamental health interventions to achieve safe motherhood, and the United Nations Children's Fund has introduced it as one of the seven strategies for child survival (1). According to the UN Millennium development goal five, contraceptive use and reduction of unmet needs for FP are essential in promoting maternal health (2). Since FP plays a vital role in addressing gender issues, poverty, and health, it is considered a key factor in achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (3).

Family planning services (FPs) become even more important when women have certain health conditions such as cancer. Although cancer treatment methods can affect reproductive ability and reduce ovarian reserve, women may remain fertile during treatment (4-8). Accordingly, using the proper contraception method is of great importance, as pregnancy during treatment can cause many complications and threaten the health of the mother and the unborn baby (9-11). Women experience a significant psychological burden during the diagnosis and treatment of cancer; therefore, pregnancy during this period can be devastating (5) and disrupt the treatment and recovery processes (11). Existing research suggests that some women, even when their life is at risk, may avoid treatment for fear of fetal side effects (12). Despite the importance of contraception use among patients with chronic diseases, little attention has been paid to this topic and FP counseling among women undergoing cancer treatment (13, 14).

Cancer is the third leading cause of mortality in Iran, with a rising trend in recent years (15-18) and an annual incidence rate of 70,000 cases (1). Sistan and Baluchestan province, southeast of Iran, ranks the lowest among Iranian provinces in terms of human development indices (19), and 25.0% of women aged 14 to 44 years in this province are illiterate (20). The results of the 2017 census in Iran reveal this province has the highest total fertility rate (3.96) (21, 22). The province also has a high rate of unintended pregnancy (27.0%) (23), which can imply the desire for a higher number of children, the low prevalence of contraception use, high rates of contraceptive failure, and unmet needs for FP compared to other parts of Iran. Moreover, the high prevalence of cancer in this province (24-27) indicates women’s high vulnerability to cancer and potential risk of unintended pregnancy and complications during pregnancy.

Accordingly, this study investigates the prevalence of contraception use and evaluates the role of some demographic, socio-cultural factors, fertility desires, and care providers in contraception use among women of reproductive age who were undergoing cancer treatment in Zahedan, the capital of Sistan and Baluchestan province in Iran. This study makes a significant contribution to research on FP among women suffering from cancer and provides fresh insights into the role of physicians and FP service providers in reducing health-related problems during cancer treatment for women and their children.

2. Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on female patients of reproductive age (15 - 49 years) who were undergoing cancer treatment. Data were collected in Zahedan, the capital of Sistan and Baluchestan province, southeast Iran. Given the unknown number of women receiving cancer treatment, all eligible female patients with cancer admitted to the three study locations (Imam Ali Hospital, Khatam Hospital, and the office of Dr. Hashemi, an oncologist) from November 2019 to May 2020 were considered. These locations were selected because they are the main centers providing cancer treatment services in Zahedan. Thus, the study population included women from both urban and rural areas who referred to these centers for cancer treatment. Subjects were determined through the convenience sampling method. The inclusion criteria were the ability to conceive, no menopause, and cohabitation with a husband (even periodically). Exclusion criteria included infertility, a diagnosis of cancer leading to the removal of reproductive organs, unwillingness to participate in the interview, and being in very poor physical condition. Finally, 133 out of 185 women who met the inclusion criteria participated in the study.

Regarding data collection, depending on the patient’s situation, the questionnaire was either self-administered or researcher-administered. The data were collected using a researcher-made questionnaire designed by the researchers, consisting of three major parts. The first part was a cover letter describing the objectives of the study and providing necessary information. The second part included questions about the sociocultural and demographic characteristics of the participants. The third part comprised questions about contraception use and knowledge about contraceptives. The content validity test was conducted to confirm the validity of the questionnaire. For this purpose, the designed questionnaire was distributed among three experts in medicine, public health, and sociology to check the accuracy of the questions and the structure of the questionnaire. The content validity score was calculated, and questions with a score of 0.85 and higher were maintained in the questionnaire. The face validity of the questionnaire was confirmed as its main questions were adapted from earlier studies (28, 29). Furthermore, one month before the main study, a pilot study was carried out on 15 women to investigate the reliability of the questionnaire in terms of comprehensibility of the questions for different groups of women and to identify any barriers to data collection. Cronbach’s alpha for all subscales was above 0.75.

After data collection, descriptive and inferential statistics were used. Pearson’s chi-square test was employed to find variations in the use of contraceptives in the three groups. Multinomial logistic regression analysis was also used to understand the major predictors of contraception use. The odds ratio (OR) was measured at a 95% confidence interval (CI). The maximum likelihood method was used to estimate the coefficients of the logistic regression models. “No contraception method” was considered the reference category. All variables with a P-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed in SPSS (version 18).

The most important ethical issues observed in this study were informed consent and the voluntary nature of participation. Patients were assured about the confidentiality of their information. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1398.218).

3. Results

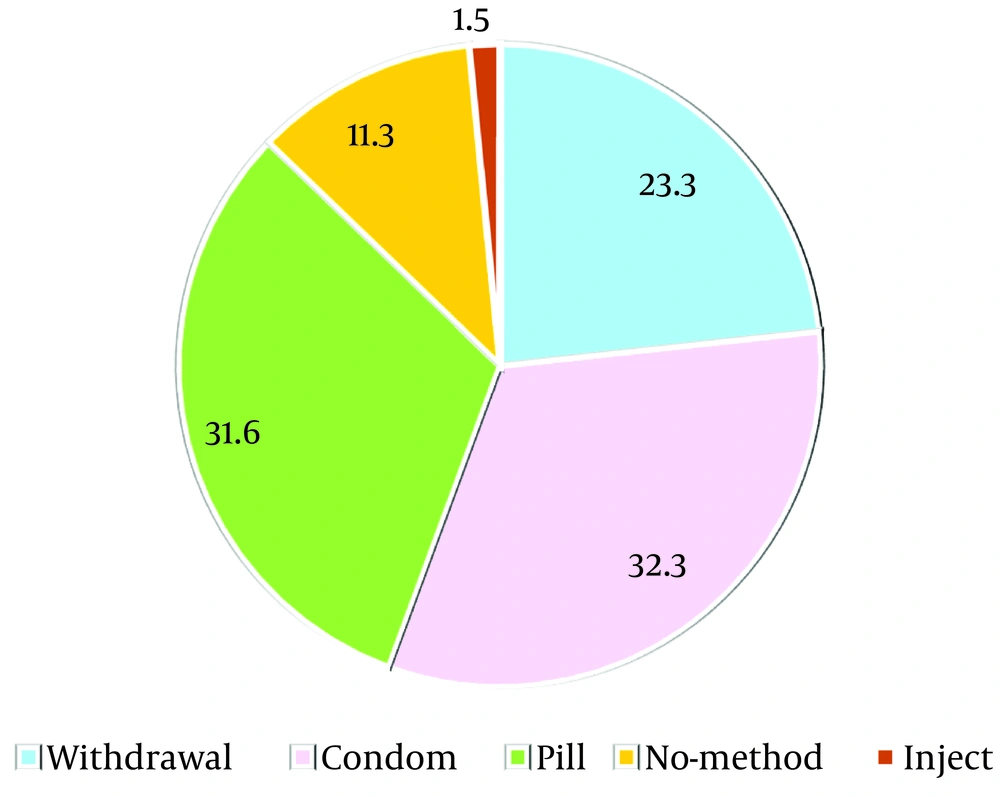

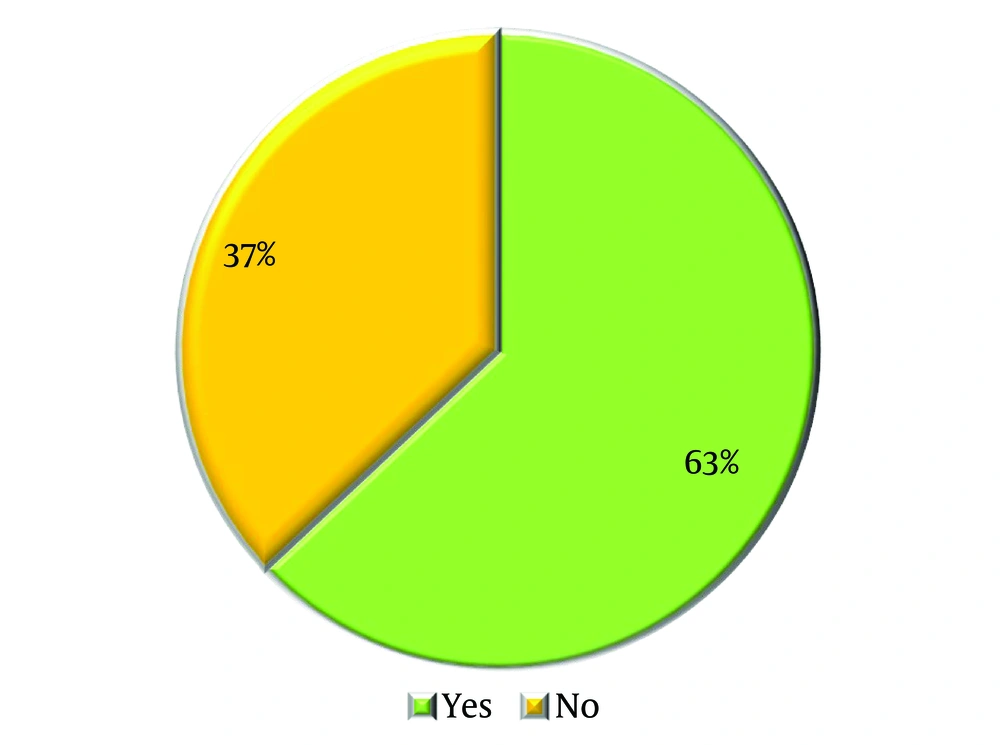

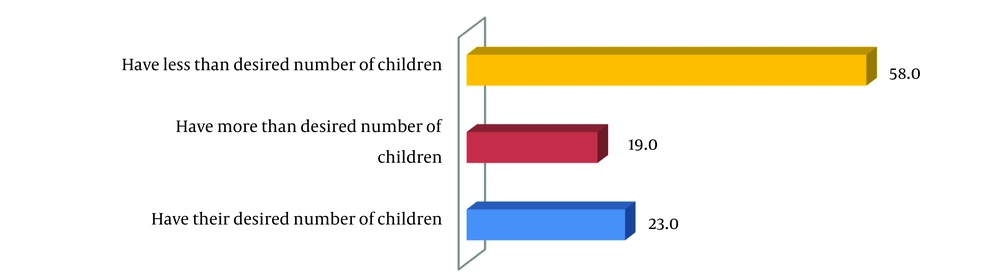

Figure 1 shows that 66.0% of the respondents used modern contraceptives during the last three months, including the pill (32.0%), male condom (32.0%), and injection (1.5%). Additionally, the traditional method (withdrawal) was used by 23.0% of women, and 11.0% of participants did not use any contraceptives in the last three months. Figure 2 indicates that 37.0% of respondents did not have knowledge about emergency contraception methods. Figure 3 illustrates that only 23.0% of women had their desired number of children, while 58.0% desired to have more children.

3.1. Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics of Participants and Some Aspects of their Fertility and Health-Related Behaviors

The mean age of participants was 36.11 ± 8.75 years. Table 1 indicates that 46.6% of participants reported an age difference of 3 to 6 years with their husbands. Regarding educational background, 12.0% of the women and 14.0% of their husbands were illiterate. Approximately 77.0% of the interviewees lived in urban areas, while 23.0% resided in rural areas, with the majority (72.0%) being homemakers. Additionally, 16.5% of participants mentioned that their husbands had another wife or other wives. In terms of religion, 49.6% of the women were Shia Muslims, and 50.4% were Sunni Muslims.

| Variables | Total | Current Status of Contraception Use | Chi-square | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawal | Modern | No Method | ||||

| Age group (y) | 14.71 | 0.065 | ||||

| 15 - 24 | 11 (8.3) | 2 (18.2) | 7 (63.6) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| 25 - 29 | 24 (18.0) | 2 (8.3) | 20(83.3) | 2 (8.3) | ||

| 30 - 34 | 28 (21.1) | 10 (34.6) | 17 (61.5) | 1 (3.8) | ||

| 35 - 39 | 26 (19.5) | 9 (34.6) | 16 (61.5) | 1 (3.8) | ||

| 40 - 44 | 23 (17.3) | 5 (23.1) | 11 (50.0) | 7 (26.9) | ||

| 45 - 49 | 21 (15.8) | 6 (26.1) | 14 (67.4) | 1 (6.5) | ||

| Spousal age difference (y) | 9.54 | 0.145 | ||||

| < 3 | 31 (23.3) | 5 (16.1) | 24 (77.4) | 2 (6.5) | ||

| 3 - 6 | 62 (46.6) | 12 (19.4) | 44 (71.0) | 6 (9.7) | ||

| 7 - 10 | 29 (21.8) | 9 (31.0) | 15 (51.7) | 5 (17.2) | ||

| > 10 | 11 (8.3) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (18.2) | ||

| Education level (y) | 17.25 | 0.008 b | ||||

| Illiterate | 16 (12) | 6 (37.5) | 8 (50.0) | 2 (12.5) | ||

| 1 - 5 | 37 (27.8) | 14 (37.8) | 17 (45.9) | 6 (16.2) | ||

| 6 - 12 | 41 (30.8) | 9 (22.0) | 28 (68.3) | 4 (9.8) | ||

| 12 + | 39 (29.3) | 2 (5.1) | 34 (87.2) | 3 (7.7) | ||

| Husband’s education level | 11.74 | 0.068 | ||||

| Illiterate | 19 (14.3) | 5 (26.3) | 10 (52.6) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| 1 - 5 | 35 (26.3) | 14 (40.0) | 18 (51.4) | 3 (8.6) | ||

| 6 - 12 | 36 (27.1) | 7 (19.4) | 26 (72.2) | 3 (8.3) | ||

| 12 + | 43 (32.3) | 5 (11.6) | 33 (76.7) | 5 (11.6) | ||

| Occupation | 4.76 | 0.092 | ||||

| Homemaker | 96 (72.2) | 27 (28.1) | 58 (60.4) | 11 (11.5) | ||

| Employee | 37 (27.8) | 4 (10.8) | 29 (78.4) | 4 (10.8) | ||

| Polygamy | 17.39 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 22 (16.5) | 10 (45.5) | 6 (27.3) | 6 (27.3) | ||

| No | 111 (83.5) | 21 (18.9) | 81 (73.0) | 9 (8.1) | ||

| Place of residence | 0.997 | 0.608 | ||||

| Urban | 102 (76.7) | 22 (21.6) | 69 (67.6) | 11 (10.8) | ||

| Rural | 31 (23.3) | 9 (29.0) | 18 (58.1) | 4 (12.9) | ||

| Religion | 4.63 | 0.099 | ||||

| Muslim (shia) | 66 (49.6) | 12 (18.2) | 49 (74.2) | 5 (7.6) | ||

| Muslim (sunni) | 67 (50.4) | 19 (28.4) | 38 (56.7) | 10 (14.9) | ||

Comparison of Contraception Use Based on Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics of Respondents (N = 133) a

Table 2 reports selected aspects of patients’ fertility behavior and contraception use. Notably, the desired number of children was high, with 87.2% of the women desiring three or more children. Furthermore, 47.4% and 16.5% of the women did not agree with their husbands about the desired number of children and the contraception method, respectively. Specifically, 45.8% of the women mentioned that their husbands desired more children, and 49.6% expressed their plan for a future pregnancy.

| Variables | Total | Current Status of Contraceptive Use | Chi-square | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawal | Modern | No Method | ||||

| Number of live children | 4.66 | 0.324 | ||||

| 0 - 2 | 33 (24.8) | 5 (15.2) | 25 (75.8) | 3 (9.1) | ||

| 3 - 4 | 52 (39.1) | 11 (21.2) | 36 (69.2) | 5 (9.6) | ||

| 4 + | 48 (36.1) | 15 (31.3) | 26 (54.2) | 7 (14.6) | ||

| Desired number of children | 17.25 | 0.008 b | ||||

| 1 - 2 | 17 (12.8) | 2 (11.8) | 13 (76.5) | 2 (11.8) | ||

| 3 - 4 | 58 (43.6) | 10 (17.2) | 44 (75.9) | 4 (6.9) | ||

| 4 + | 58 (43.6) | 19 (32.8) | 30 (51.7) | 9 (15.5) | ||

| Couple’s agreement on the number of children | 2.47 | 0.071 | ||||

| Yes | 70 (52.6) | 14 (20.0) | 50 (71.4) | 6 (8.6) | ||

| No | 63 (47.4) | 17 (27.0) | 37 (58.7) | 9 (14.3) | ||

| Couple’s agreement on the contraception method | 9.22 | 0.010 b | ||||

| Yes | 111 (83.5) | 24 (21.6) | 78 (70.3) | 9 (8.1) | ||

| No | 22 (16.5) | 7 (31.8) | 9 (40.9) | 6 (27.3) | ||

| Doctor discussed contraceptives | 11.12 | 0.004 b | ||||

| Yes | 71 (53.4) | 17 (23.9) | 52 (73.2) | 2 (2.8) | ||

| No | 62 (46.6) | 14 (22.6) | 35 (56.5) | 13 (21.0) | ||

| Intention to become pregnant | 0.0912 | 0.634 | ||||

| Yes | 66 (49.6) | 16 (24.2) | 41 (62.1) | 9 (13.6) | ||

| No | 67 (50.4) | 15 (22.4) | 46 (68.7) | 6 (9.0) | ||

| Distance from health center (min) | 16.26 | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 30 | 123 (92.5) | 30 (24.4) | 83 (67.5) | 10 (8.1) | ||

| 30 - 60 | 10 (7.5) | 1 (10.0) | 4 (40.0) | 5 (50.0) | ||

| Distance from pharmacy (min) | 2.04 | 0.361 | ||||

| < 30 | 114 (85.7) | 27 (23.8) | 75 (65.4) | 12 (10.8) | ||

| 30 - 60 | 19 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | ||

Comparison of Contraception Use Based on Fertility Behavior and Desires (N = 133) a

Regarding accessibility, the majority of participants could reach health centers (92.5%) and pharmacies (85.7%) within less than 30 minutes. Additionally, 46.6% of the patients reported that the physician responsible for their cancer treatment never discussed contraception.

3.2. Comparison of Contraception Methods

As shown in Tables 1, and 2, significant differences in the frequency of contraception methods were observed in relation to several factors. These factors include education level (P = 0.008), polygamy (P = 0.000), desired number of children (P = 0.008), couple’s agreement on the contraception method (P = 0.010), physician consultation about contraception (P = 0.004), and distance from health centers (P = 0.000). Specifically, the highest prevalence of traditional contraception methods and non-use of contraception was found among illiterate women; women with primary education; women living in polygamous families; women desiring to have more than four children; women who did not agree with their husbands about the contraception method; women who did not receive any physician consultation; and women who lived far from health centers (about 30 - 60 minutes).

3.3. Prediction of Contraception Use

The results of the multinomial logistic regression analysis of the main predictors of contraception use are presented in Table 3. There was no significant difference between the predicted and observed models and values, as the P-value of the Hosmer-Lemeshow (H-L) test was higher than 0.05 (non-significant). We found that two variables—physician consultation (OR = 13.64, 95% CI: 2.13 - 87.32, P = 0.006) and couple’s agreement on contraception method (OR = 9.91, 95% CI: 1.69 - 58.15, P = 0.011)—are the main predictors of using contraception rather than no method. In other words, the likelihood of contraception use versus non-use was significantly higher among women who received contraception consultation and among couples who had agreement on the contraception method.

| Predictors | OR | P-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.035 | 0.636 | 0.910 - 1.17 |

| Spousal age difference | 0.986 | 0.828 | 0.867 - 1.12 |

| Desired number of children | 0.892 | 0.657 | 0.537 - 1.48 |

| Number of live children | 0.996 | 0.988 | 0.565 - 1.75 |

| Distance from health centers | 0.960 | 0.104 | 0.913 - 1.02 |

| Distance from pharmacy | 0.949 | 0.053 | 0.901 - 1.10 |

| Respondent's education level | |||

| Illiterate | Baseline | ||

| 1 - 5 | 0.342 | 0.405 | 0.027 - 4.27 |

| 6 - 12 | 0.787 | 0.865 | 0.049 - 12.54 |

| 12+ | 3.205 | 0.544 | 0.074 - 13.33 |

| Husband's education level | |||

| Illiterate | Baseline | ||

| 1 - 5 | 0.698 | 0.822 | 0.031 - 15.85 |

| 6 - 12 | 4.563 | 0.269 | 0.309 - 67.44 |

| 12+ | 0.985 | 0.990 | 0.084 - 11.56 |

| Want to be pregnant in future | |||

| Yes | 0.340 | 0.193 | 0.067 - 1.72 |

| No | Baseline | ||

| Job | |||

| Employed | 0.792 | 0.818 | 0.109 - 5.74 |

| Homemaker | Baseline | ||

| Residential Place | |||

| Urban | 1.10 | 0.994 | 0.116 - 8.73 |

| Rural | Baseline | ||

| Consultation with physician about contraception | 0.006 | 2.13 - 87.32 | |

| Yes | 13.64 | ||

| No | Baseline | ||

| Couple’s agreement on contraception method | 0.011 | 1.69 - 58.15 | |

| Yes | 9.91 | ||

| No | Baseline | ||

| Couple’s agreement on the number of children | 0.682 | 0.357 - 4.63 | |

| Yes | 1.28 | ||

| No | Baseline | ||

| Polygamy | 0.457 | 0.344 - 13.52 | |

| Yes | Baseline | ||

| No | 1.17 | ||

| Religion | 0.287 | 0.324 - 4.22 | |

| Muslim (shia) | 1.32 | ||

| Muslim (sunni) | Baseline |

Determinants of Contraception Use

4. Discussion

Despite the critical importance of contraception during cancer treatment, the results of this study indicated that about one out of three women undergoing cancer treatment are at risk of unintended pregnancy. Additionally, around one out of three women revealed they did not have adequate knowledge about emergency contraception methods. Similarly, a study based on the web-based Basel Breast Cancer Database at the University Women's Hospital Basel (Switzerland) found that 42.0% of patients did not use contraception or used an ineffective method (5). Kopeika et al. conducted a study between 2011 and 2013 on women with breast cancer in the UK and found that 66.0% of women at the time of the survey were not using any contraception, and 64.0% of those who did not use contraception did not intend to become pregnant (30). While several studies have demonstrated that a high rate of unintended pregnancies and abortions occurs among withdrawal users (31, 32), we found that a considerable percentage of participants in the present study used the withdrawal method for contraception.

The results of this study revealed that physician consultation about contraception is one of the main predictors of contraception use among women. Moreover, significantly higher rates of withdrawal and non-use of contraception were reported among women who did not receive physician consultation about contraception. However, 46.6% of respondents claimed that the physician responsible for their cancer treatment did not talk to them about contraception. These results align with studies suggesting that women who receive contraception counseling from a physician are more likely to use contraception compared to those who do not seek counseling (33, 34). A qualitative study on women diagnosed with breast cancer in Cape Town, South Africa, also revealed that patients received limited information from healthcare providers about fertility preservation options, contraceptive use, and the impacts of cancer treatment on their future fertility (35). The study by Mody et al. on women with a history of cancer in Athens, Greece, showed that 90% of respondents acknowledged using contraception, with the most common method being condoms. However, 49% of these individuals did not receive specific advice from their healthcare provider about a contraceptive method (36).

A set of various factors can influence receiving consultation on contraception use and fertility. Reports suggest that around the time of cancer diagnosis and treatment, conversations about contraception are less common in clinical settings because care providers primarily focus on treatment, leaving little room for contraception counseling. Additionally, some women may not feel culturally comfortable discussing their sexual relationships and contraception-related issues (36-39).

Education level is another important factor that can affect one's understanding not only of the consequences of pregnancy during cancer, desired number of children, and suitable contraception methods but also the physician’s advice regarding pregnancy and contraception use. Crafton et al. (40) reported that around 50% of oncologists believe their patients do not understand the possibility of pregnancy during treatment. Accordingly, it is critical that care providers pay attention to the demographic and cultural background of patients, offer timely advice about reproductive needs, and highlight the importance of contraception and the risks of pregnancy during treatment. Additionally, it would be helpful if oncologists refer patients to gynecologists to ensure they receive proper contraception methods (5, 34, 41-43).

According to the findings of the present study, the highest rates of withdrawal method and non-use of contraception were reported by illiterate women and those with primary education. Generally, couples with lower levels of education are less likely to be aware of contraceptives and the complications of pregnancy during cancer treatment. Therefore, the rate of contraception use is lower and the tendency toward traditional contraceptives is higher among them. This finding is in line with the results of another study in Sistan and Baluchestan province (29), but in contrast to those reported by Erfani and Yuksel-Kaptanoglu (44) and Asadi Sarvestani and Khoo (45), which found that the prevalence of traditional contraceptives was higher among women with tertiary education compared to women with elementary education.

In line with another study (29), the results showed that the desired number of children was another effective factor in contraception use. The desire to have more children indicates that women were less interested in using contraception, particularly modern methods. Additionally, older women and women with lower education expressed the desire to have more children. As most participants (87.0%) in this study desired to have more than two children, and around 60.0% of respondents had fewer than their desired number of children, care providers should pay enough attention to this factor during counseling sessions.

Polygamy was another important factor, as the highest rates of withdrawal use and non-use of contraceptives were reported among women whose husbands had one or more other wives. This finding is consistent with other studies, which suggest lower rates of contraception use among women in polygamous families compared to their peers in monogamous relationships (46). The lower rate of contraception and the higher tendency toward using the withdrawal method are mainly because fertility is regarded as a source of power for women in polygamous families in Sistan and Baluchestan province. Moreover, polygamy is more widespread among people with a lower level of education, which is also one of the effective factors in contraception use.

In summary, couples’ agreement about the contraception method was another predictor of contraception use and its type. The highest rate of contraception use and modern contraceptive use were reported among women who agreed with their husbands about contraception methods. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which found a significant relationship between contraception use and the couple’s agreement about contraception methods. It is documented that women whose husbands agree with contraception use are more likely to embrace a modern contraceptive method compared to women whose husbands disapprove of contraception (47, 48).

Distance from health centers also showed a significant relationship with contraception use. About 91.9% of the studied women who lived close to a health center (less than 30 minutes away) protected themselves from pregnancy by using modern and traditional methods, while only half of those who were 30 to 60 minutes away from the health centers used birth control methods. These results highlight the vital role of health centers in providing contraceptives and related knowledge. However, it should be noted that this study was conducted before recent limitations in access to FPs. Specifically, since 2012, Iran officially changed its population policy from anti-natalist to pro-natalist (49, 50). Based on the new population policy, free FPs stopped and access to contraceptives became limited to increase fertility rates (29-31).

Until the summer of 2020, certain groups such as women with specific diseases, women under age 18 and over 40, women with a child below 3 years of age, women with a history of four cesarean sections, as well as poor women and those living in regions above the replacement rate had free access to FPs (49-51). Moreover, until the approval of “The Youthful Population and Protection of the Family Law” in 2021, pills and condoms were accessible via pharmacies at an affordable price for the majority of the population (49). Since 2021, based on the aforementioned law, the free distribution of contraceptives stopped, and access to contraceptives is now subject to a doctor’s prescription (52).

In addition, before these changes in population policy, local health centers (Khaneh Behdasht in Persian) played an essential role in providing FPs, particularly in rural areas. In many rural areas of Iran, these centers were the only sources of access to contraceptives and acquiring knowledge about birth control (53-55). Therefore, policymakers should be careful about the consequences of changes in access to FPs for women’s health and their children. Furthermore, the health care system should pay more attention to women with certain diseases such as cancer, particularly those from disadvantaged socioeconomic groups who live in rural areas and less developed places.

4.1. Conclusions

Overall, the results of this study indicate that contraception use is affected by a range of sociocultural and accessibility factors. Accordingly, care providers should pay attention to these factors and inform female patients with cancer about the importance of contraception use during cancer treatment. Women with lower education levels, those who live in polygamous families, and those in less developed areas need more support in this regard. Meanwhile, supporting all women during illness in terms of FP and reproductive health services requires establishing a coherent and strong communication network between care providers, FP providers, and couples.