1. Background

Colon cancer is one of the most common neoplasms worldwide, increasing exponentially with age (1). Globally, it is the third most common cause of death among malignancies and accounts for the second-highest number of disability-adjusted life years (DALY) among neoplastic diseases (2). In Iran, colon cancer is on the rise, representing the third most common malignancy among women and the fourth most common malignancy among men (3).

Initially, Bufill indicated that the proximal side of the colon had different biological, histopathological, molecular, and inherited genetic characteristics from the distal side, leading to dissimilar pathological characteristics and mechanisms between right-sided colon cancer (RCC) and left-sided colon cancer (LCC). The different embryological origins of the right (cecum, ascending colon, and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon) and left colon (the distal one-third of the transverse colon plus the descending and sigmoid colons) play a significant role in the differences in susceptibility to neoplastic transformation between RCC and LCC (4). Kwak and Ju revealed that RCC had more mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, whereas LCC did not have any significant special carcinogenesis pathways (5). In contrast, Lee et al. explained that microsatellite instability (MSI), BRAF, and KRAS gene mutations had fundamental roles in RCC, whereas chromosomal instability was related to LCC (6).

A survey in Germany illustrated that the prognosis of RCC is worse due to factors such as patient age, time of diagnosis, and genetic predispositions (7). Additionally, a Greek study found that RCC is associated with shorter overall survival, attributed to its molecular characteristics and poorer response to medication (8). In contrast, Fukata et al. reported that patients with LCC exhibited poorer recurrence-free survival in stage II, which they attributed to the biological aggressiveness of LCC. However, both RCC and LCC groups demonstrated similar overall survival rates, regardless of cancer stage (9).

2. Objectives

Given these disparities in the literature, our objective was to compare survival, recurrence, and metastasis rates between RCC and LCC and to assess predictors of overall survival, utilizing a 12-year dataset from an Iranian cohort of patients with colon cancer.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study recruited all patients who had undergone surgery with a diagnosis of colon carcinoma at Shahid Faghihi Hospital (Shiraz, Iran) between March 2010 and March 2022. The inclusion criteria were all patients who had colon surgery. Excluded were those with other types of cancer in addition to colon cancer, cases of rectal resection, and cases with both RCC and LCC. The sample size was determined using a prior study comparing survival rates of right and LCC (10), with MedCalc software. Considering a five-year overall survival of 87% for right-sided and 96.5% for LCC, with a power of 90 and α = 0.05, the sample size was calculated to be 364. Accounting for a 20% increase, the final sample size was 443 eligible patients, with 231 having RCC and 212 having LCC. Patients requiring chemotherapy received the same medications in both groups, and in cases with positive lymph nodes, an oxaliplatin-based regimen (FOLFOX or XELOX) was prescribed. This study was registered with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (No. 22430) and approved by the University Research Ethics Committee (Code: IR.SUMS.MED.REC.1400.315).

3.2. Data Collection

Data were collected from the Shiraz Colorectal Cancer Surgery (SCORCS) registry, a web-based electronic database belonging to Shahid Faghihi Hospital, affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. This registry has included patients who have undergone colorectal surgery at this tertiary center since 2007. All patients included in the study had a confirmed diagnosis of colon cancer, as indicated by a pathological report from intestinal tissue samples taken before surgery. Following tumor resection, an expert pathologist examined each tumor, and the final report and diagnosis were recorded in SCORCS. Additionally, information regarding metastasis, follow-ups, and invasions was regularly updated in the database (11). Right-sided colon cancer was defined as a tumor from the cecum to the first two-thirds of the transverse colon, while LCC was defined as a tumor from the splenic flexure to the sigmoid colon.

Each patient admitted to the colorectal department with a confirmed diagnosis of RCC or LCC was referred by the head nurse to the data registry team. The team, under the supervision of one epidemiologist and one expert colorectal surgeon, recorded and validated the patients' data in the SCORCS database. During admission, patients signed an informed consent form and provided contact information to aid in completing the database. The registry team encouraged patients to attend regular follow-up visits, which helped maintain database accuracy.

The information collected from SCORCS included age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, tumor site, tumor size, number of involved lymph nodes, vascular invasion, neural invasion, lymphatic invasion, type of operation, death status, recurrence status, metastasis status, time to follow-up, time to death, time to recurrence, and time to metastasis.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows v.21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Qualitative variables are presented as frequency and percentage, and quantitative variables are provided as mean and standard deviation. The normality of quantitative data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilks test. Inferential statistics included the chi-square test to evaluate differences in categorical variables between RCC and LCC, and the independent two-sample t-test for quantitative variables. Survival analysis and Kaplan-Meier curves were employed to compare the survival distributions of patients with RCC or LCC. Significance was assessed using the log-rank test or Breslow test. All P-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Results

Our study included 443 patients with confirmed colon cancer: 231 with RCC and 212 with LCC. As summarized in Table 1, 58% of RCC patients and 49% of LCC patients were male (135 and 104 patients, respectively), representing a significantly greater proportion of males in the RCC group (P = 0.04). The mean age was 58.12 ± 13.73 years in RCC patients and 56.38 ± 14.09 years in LCC patients. Most patients were of the Fars ethnicity (77% in RCC and 78% in LCC), and the majority were married. The mean tumor size was 5.35 ± 2.24 cm in RCC and 5.04 ± 2.89 cm in LCC. There was no significant difference between RCC and LCC patients regarding age (P = 0.20), ethnicity (P = 0.91), marital status (P = 0.50), or tumor size (P = 0.20). However, a significant difference was observed between RCC and LCC patients regarding the stage of disease (P < 0.001).

| Variables and Levels | RCC (n = 231) | LCC (n = 212) | Total (n = 443) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, (y) | 58.12 ± 13.73 | 56.38 ± 14.09 | 57.29 ± 13.92 | 0.20 b |

| Sex | 0.04 c | |||

| Male | 135 (58) | 104 (49) | 239 (54) | |

| Female | 96 (41) | 108 (51) | 204 (46) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.91 c | |||

| Fars | 177 (77) | 165 (78) | 342 (77) | |

| Lor | 18 (8) | 17 (8) | 35 (8) | |

| Other | 36 (16) | 30 (14) | 16 (15) | |

| Marital Status | 0.50 d | |||

| Divorced | 1 (< 1) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) | |

| Married | 197 (85) | 189 (89) | 386 (87) | |

| Single | 31 (13) | 21 (10) | 52 (12) | |

| Widowed | 2 (< 1) | 2 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) | |

| Size of tumor, (cm) | 5.35 ± 2.24 | 5.04 ± 2.89 | 5.20 ± 2.58 | 0.20 b |

| Stage of disease | < 0.001 c | |||

| Stage I | 37 (16) | 42 (20) | 79 (18) | |

| Stage II | 87 (38) | 76 (36) | 163 (37) | |

| Stage III | 90 (39) | 75 (35) | 165 (37) | |

| Stage IV | 17 (7) | 19 (9) | 36 (8) |

Demographic Characteristics of Patients with Right-Sided and Left-Sided Colon Cancer a

Among all patients, 61% (269) underwent laparoscopy (150 [65%] in RCC and 119 [56%] in LCC), while 30% (131) required conversion from laparoscopy to laparotomy (61 [26%] in RCC and 70 [33%] in LCC), and the rest underwent laparotomy (P = 0.17). In terms of surgery type, 211 (91%) patients with RCC had a right hemicolectomy, 203 (96%) patients with LCC had a left hemicolectomy, and 29 patients underwent a total colectomy. On average, 15 lymph nodes were resected during the operation (R0), with approximately 16 lymph nodes in RCC cases and 13 in LCC cases. Malignancy was found in an average of 2 resected lymph nodes (R1), with 2 in RCC and 1 in LCC, showing no significant difference between the groups in terms of the number of malignant resected lymph nodes (P = 0.67). Additionally, around 90% of patients in both groups had free radial margins.

Ulcerative, polypoid, and fungating tumor appearances were the most common presentations across all patients. Notably, LCC cases had a significant presence of ulcerative tumors (57 patients), while fungating tumors were significantly more common in RCC (56 patients) (P = 0.03). The tumors of 263 patients were well-differentiated, with a greater proportion in LCC than in RCC (65% vs. 51%, P = 0.003). Furthermore, 52% of RCC patients presented with obstruction. As shown in Table 2, vascular, perineural, and lymphatic invasions were significantly more frequent in RCC than in LCC (P = 0.001). In a subgroup analysis by disease stage, we found no significant differences in perineural or lymphatic invasion between RCC and LCC at various stages. However, vascular invasion was notably more prevalent among stage III RCC patients compared to LCC patients (39% vs. 20%, P = 0.01) (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File).

| Invasion | RCC (n = 231) | LCC (n = 212) | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular | 62 (27) | 38 (18) | 0.001 |

| Perineural | 40 (17) | 30 (14) | 0.001 |

| Lymphatic | 65 (28) | 53 (25) | 0.001 |

Invasions Among Patients with Right-Sided and Left-Sided Colon Cancer

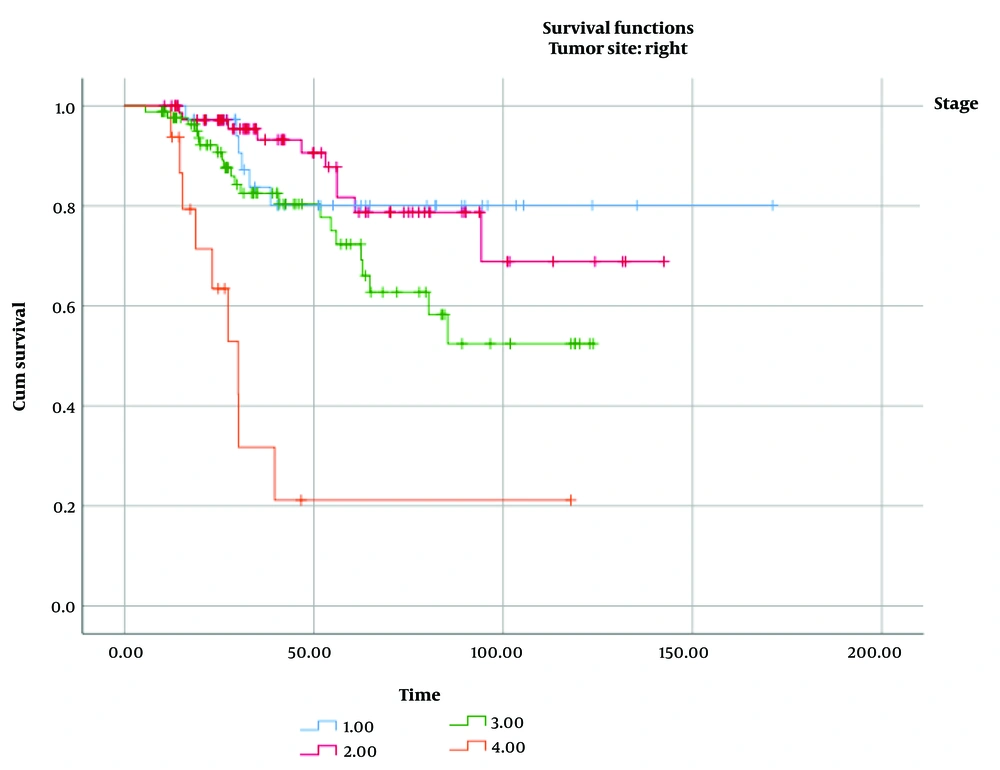

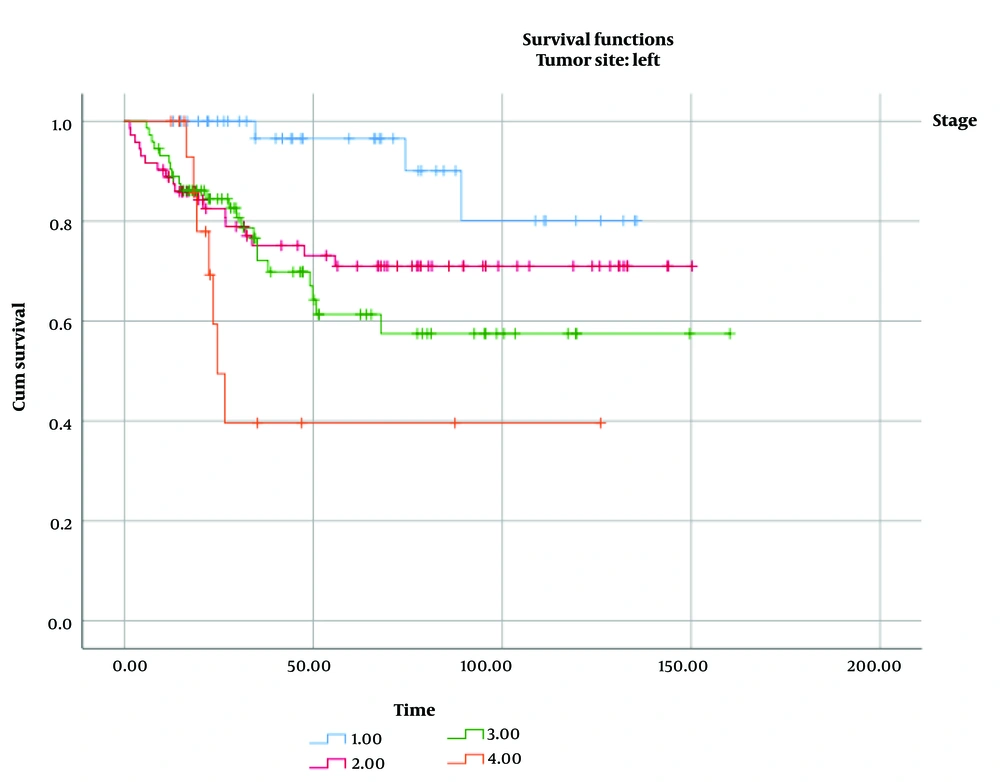

Among all cases, 16% of RCC and 20% of LCC were classified as stage I; 38% of RCC and 36% of LCC were stage II; 39% of RCC and 35% of LCC were stage III; and 7% of RCC and 9% of LCC were stage IV. The median follow-up time for all patients was approximately 45 months (IQR, 25 - 87). As shown in Table 3, we compared the impact of several factors on the overall survival of patients with RCC and LCC. Tumor stage was found to have a significant effect on overall survival in both RCC (P log-rank test < 0.001, Figure 1) and LCC (P log-rank test = 0.004, Figure 2).

| Variables and Levels | RCC | LCC | Chi-squared Value b | P-Value b | Chi-squared Value c | P-Value c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.79 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.78 | ||

| Male | 103.73 (6.13) | 117.71 (7.14) | ||||

| Female | 127.34 (9.22) | 106.65 (6.36) | ||||

| Ethnicity | 0.33 | 0.85 | 3.78 | 0.15 | ||

| Fars | 125.57 (6.81) | 107.70 (5.41) | ||||

| Lor | 69.53 (7.83) | 150.39 (9.49) | ||||

| Other | 109.25 (10.45) | 98.84 (11.49) | ||||

| Stage of disease | 37.33 | < 0.001 | 13.50 | 0.004 | ||

| Stage I | 143.14 (10.29) | 123.50 (6.41) | ||||

| Stage II | 116.99 (7.37) | 112.62 (7.58) | ||||

| Stage III | 88.66 (6.07) | 105.63 (9.38) | ||||

| Stage IV | 44.62 (12.01) | 63.18 (15.45) |

Results of Log Rank Test for Survival Time for Patients with Right-Sided and Left-Sided Colon Cancer a

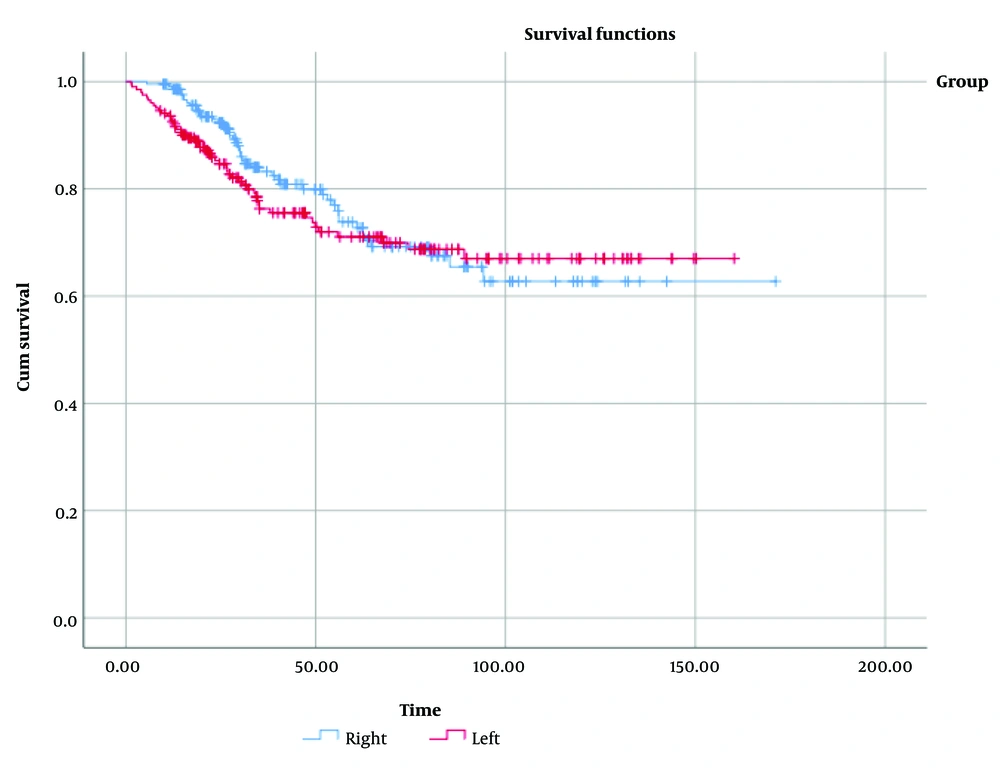

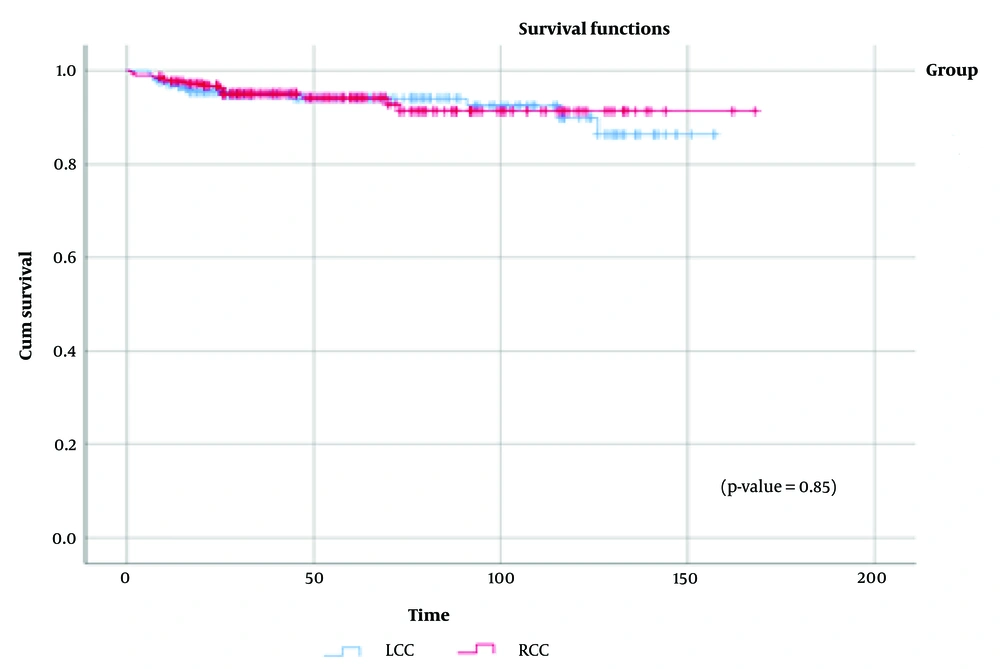

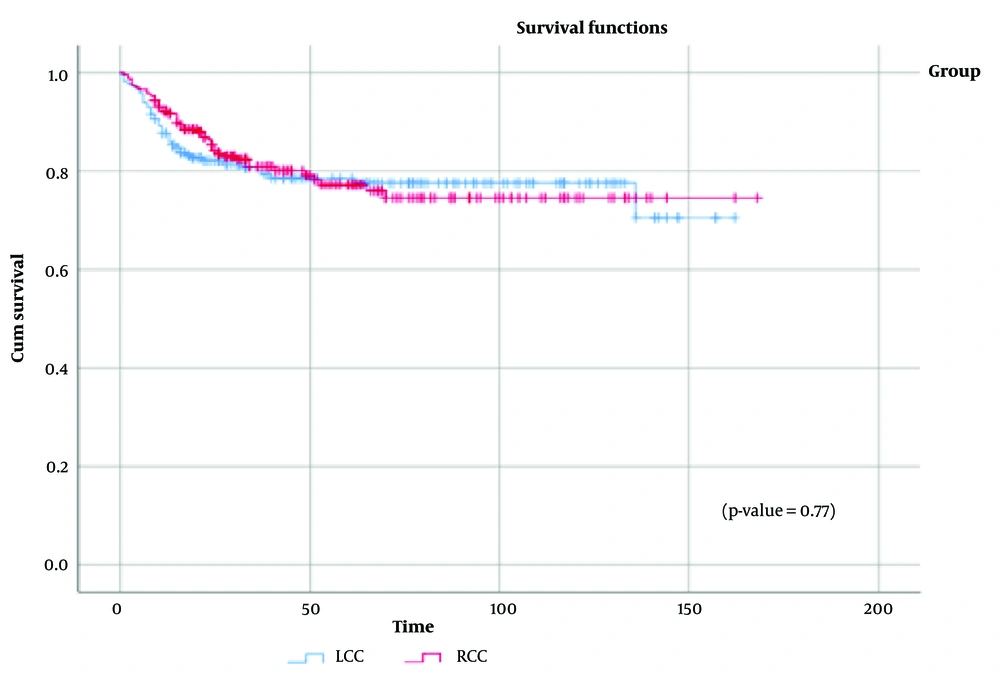

Figure 3 displays the survival distribution comparison between the RCC and LCC groups, showing a statistically similar distribution (χ² = 0.56, P = 0.45). Additionally, when data were stratified by disease stage (Appendix 2 in Supplementary File), no significant differences in overall survival were observed between RCC and LCC across stages I to IV. Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of tumor recurrence between RCC and LCC, with no significant differences found between the groups (χ² = 0.037, P = 0.85). Figure 5 presents a comparison of the metastasis rate following surgery between the two groups, which also showed no statistically significant difference (χ² = 0.084, P = 0.77).

5. Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed 12 years of data on RCC and LCC patients who underwent surgical management at a tertiary referral hospital in Shiraz, Iran. This study is the first in Iran to examine differences between RCC and LCC patients specifically. Unlike numerous studies that contrast RCC with a combination of LCC and rectal cancers, our study excluded rectal cancers from the analysis.

One of the key findings was the significantly higher rates of perineural, vascular, and lymphatic invasion in RCC patients compared with LCC patients. Additionally, we observed significant differences in vascular invasion between RCC and LCC in stage III colon cancer, whereas lymphatic and perineural invasion did not differ significantly between stages. Similarly, several studies have reported a predominance of lymphatic and perineural invasion in RCC patients (12-14), suggesting these factors may have prognostic value (14). In line with our findings, Feng et al. found that vascular invasion was significantly more common in RCC, although perineural invasion did not differ significantly among RCC, LCC, and rectal cancer (15). Kataoka et al. reported that lymphatic invasion was only distinct between RCC and LCC in stage III colon cancer (16), underscoring the importance of close follow-up and chemotherapy post-surgery.

The general trend observed in our study indicated an ulcerative tumor appearance in LCC and a fungating tumor appearance in RCC. Histologically, most cases were well differentiated. However, other studies have reported that RCCs are more often mucinous and poorly differentiated, while LCCs tend to have better differentiation compared with RCCs (8, 17, 18). Additionally, there was a significant difference in disease stage between RCC and LCC patients. Consistent with our findings, multiple studies have shown that RCC is typically diagnosed at more advanced stages (8, 19, 20). In our study, most patients in both groups were diagnosed with stage II and III colon cancer. As anticipated, overall survival decreased with higher stages in both groups.

In the present study, we observed no significant differences in overall survival rate, recurrence, or metastasis between RCC and LCC patients. Additionally, there were no significant differences in overall survival across different stages between the two groups. A four-decade population-based study in Norway also found no significant differences between RCC and LCC, except for a recently improved 5-year survival rate in LCC (19). Some studies, however, have shown that RCC patients may have a shorter survival rate than LCC patients (7, 8, 21). For example, Weiss et al. reported that stage II RCC had a lower mortality rate compared to stage II LCC, whereas stage III LCC had a lower mortality rate than stage III RCC (22). Bustamante-Lopez et al. found no significant differences in survival rates between RCC and LCC, attributing survival to disease stage alone (20). Similarly, some prior studies reported comparable overall survival rates (23) and recurrence rates (24) for RCC and LCC. Nonetheless, when comparing different stages, survival trends varied (23). A French colon cancer registry study indicated that recurrence and metastasis were similar across RCC and LCC at the 5-year survival mark, though survival trends shifted over a 10-year follow-up (25).

Discrepancies across studies may stem from variations in study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as differences in genetic and epigenetic factors, lifestyle, comorbidities, clinical and pathological disease stages, and pre- and post-operative treatments. These factors likely impact prognosis more significantly than tumor location alone.

In the current study, among demographic variables, only sex was significantly different between the RCC and LCC groups; RCC was predominantly observed in males, while LCC was more common in females. Schmuck et al. conducted a study on over 185,000 patients in Germany and reported that colon cancer (including both RCC and LCC) was more prevalent among males (26). In contrast, some studies indicate a higher prevalence of RCC in females and LCC in males (8, 9), possibly due to genetic and inherited factors.

One of the main strengths of our study was the use of accurate data from the SCORCS registry, where data are recorded, reviewed, and validated by expert teams under the supervision of specialists and epidemiologists. Additionally, we reported only pathologically confirmed cases. However, the study had several limitations. The primary limitation was the sample size, as we excluded patients with rectal tumors. Another limitation is the single-center nature of the study, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings.

5.1. Conclusions

A long-term follow-up using the comprehensive SCORCS registry provided valuable insights into the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with RCC and LCC. In summary, lymphatic, perineural, and vascular invasions were significantly more prevalent in RCC. However, both groups showed similar survival rates, recurrence patterns, and metastasis occurrences. The comparable tumor sizes between RCC and LCC in our study may suggest a correlation between clinical tumor presentation and the pathological nature of colon tumors. While this cohort study offered important findings, future research with larger national and international registries is recommended to provide a more detailed understanding of RCC and LCC characteristics.