1. Background

Opium, a highly addictive substance derived from the unripe seedpod of the poppy plant, is illicitly consumed by millions of individuals worldwide, particularly in central Asian countries (1). The prevalence of opium use in southern Iran has been reported at 8.4%, with 95.9% of users consuming Teriak in the adult population (2). While opioids are prescribed for pain relief in medical settings, their illegal use and addiction can result in serious health problems (1, 3). Opioid misuse is responsible for 66% of all drug-related deaths (4). In regions such as Asia and the Middle East, there is a belief that opium consumption has a protective effect on heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes (5). Over the past two decades, case-control and cohort studies have been conducted to investigate the effect of opium on increased cardiovascular mortality (6).

1.1. The Significance of Blood Pressure and Fasting Blood Sugar

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality worldwide (7). It is crucial to identify and control the risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease. Hypertension and diabetes are two significant risk factors for cardiovascular disease (8). The global prevalence of diabetes in adults is estimated to reach 552 million people by 2030 (9). Blood pressure is one of the most important risk factors for cardiovascular disease. By 2025, the prevalence of hypertension is expected to increase by 60%, affecting 1.56 billion people. Research indicates that high blood pressure contributes to the death of 9 million people worldwide annually (10).

2. Objectives

Given the prevalence of opium use and some beliefs regarding its potential preventive effect on cardiovascular diseases, coupled with the fact that blood pressure and plasma glucose are two significant risk factors for cardiovascular disease, this study was conducted to examine the relationship (but not causality) between blood pressure, plasma glucose, and opium use. Causal conclusions cannot be drawn without further investigation.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This study is a cross-sectional investigation based on the Fasa Prospective Epidemiological Research Study in Iran (PERSIAN) cohort study, also known as the Fasa Adults Cohort Study (FACS). The PERSIAN cohort study was designed to assess the predisposing factors for non-communicable diseases, particularly the most common ones, among the residents of the rural area of Fasa in southwest Iran.

Fasa city is located in the eastern part of Fars province, southwest Iran, with a population of approximately 250,000 people. A rural area called Sheshdeh, along with 24 surrounding villages, was selected for the cohort study, with a total population of 41,000.

People were invited to participate in the study by healthcare workers representing the primary healthcare system at each rural and small-town health center. The healthcare workers were familiar with each invited individual and were aware of the health status of all villagers in their area.

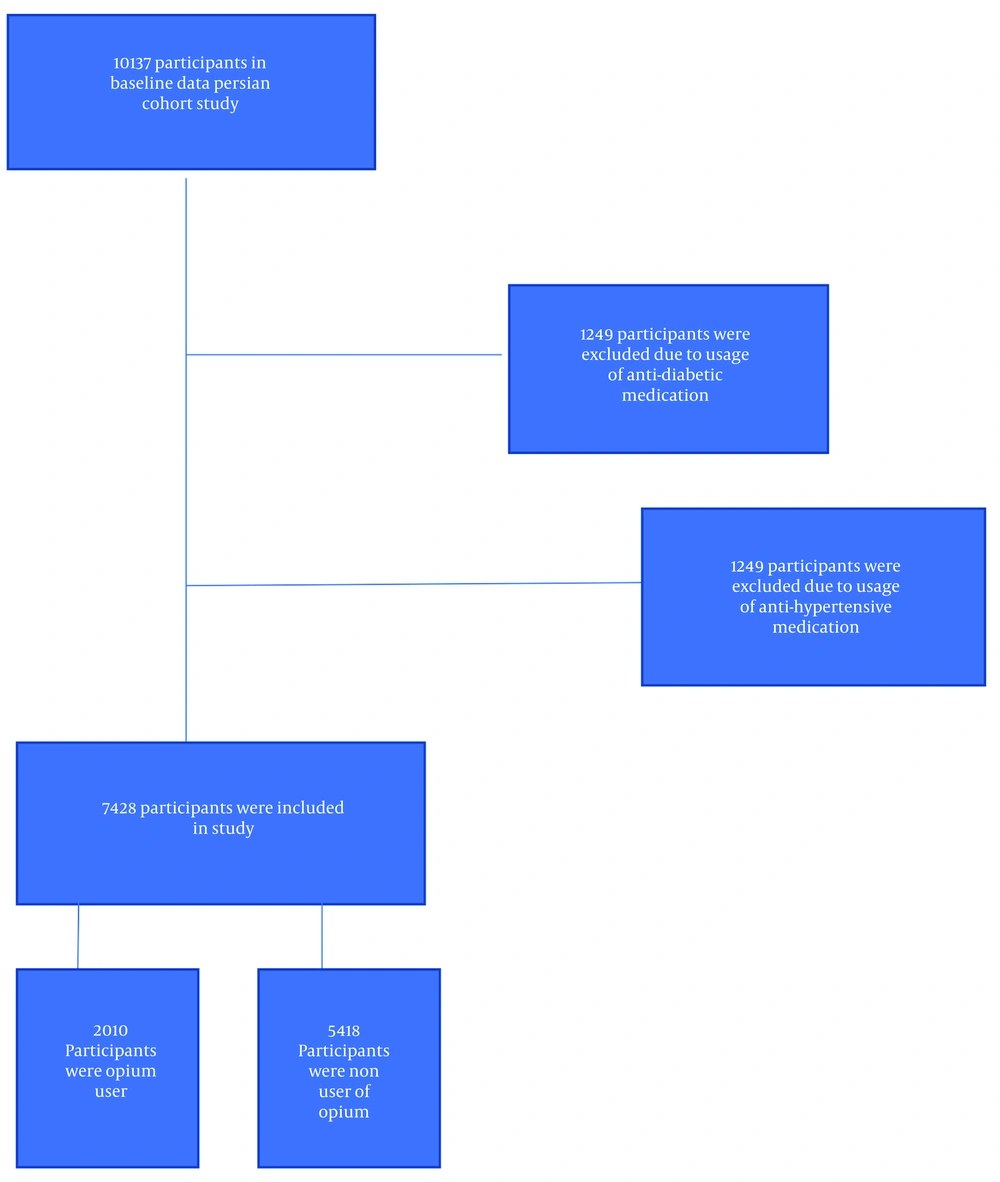

Individuals aged 35 years and older (10,137 people) were selected as the target population for this study. The protocol for the PERSIAN cohort study, a population-based mega project, was written by Farjam et al. in 2016 and Poustchi et al. in 2018 (11, 12).

Individuals with a history of high blood pressure requiring medication (1,460 people), those with diabetes under medication and physician supervision (249 people), and those with incomplete data were excluded. In the end, 7,428 individuals were included (Figure 1).

3.2. Study Instruments and Variables

After enrollment, demographic characteristics were collected, along with laboratory samples (blood, urine), general interviews, medical interviews, nutritional assessments, and physical examinations such as blood pressure and heart rate, all conducted by the responsible nurses present at the center.

Socioeconomic status was assessed using a 9-question questionnaire covering housing ownership status, housing area, number of bedrooms, number of roommates, electrical appliances, cars, number of books studied, and trips abroad and within Iran. A component analysis was performed, and based on the 33rd and 66th percentiles, the socioeconomic variable was categorized into three levels: Low (below the 33rd percentile), high (above the 66th percentile), and medium (between the 33rd and 66th percentiles).

All participants were evaluated for weight, height, and Body Mass Index (BMI), which was calculated using the formula:

BMI = Weight (kg)/Height2 (m)

Alcohol, tobacco, and opium consumption were also analyzed. Participants were asked if they were current smokers or if they frequently used opium products or alcohol.

Blood pressure was measured using a mercury sphygmomanometer. After 10 minutes of rest, blood pressure was taken from both hands while the participants were seated for 5 minutes, and the average blood pressure was recorded as the final measurement.

Fasting blood sugar samples were collected from participants and analyzed using the colorimetric method (Pars Azmoon kit).

Physical activity was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), based on MET-min/week. Calorie intake was evaluated using the validated Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed to describe quantitative variables using the mean ± SD and qualitative variables using frequency and percentage. For quantitative data, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, as well as fasting blood sugar, were compared between sociodemographic characteristics using t-tests, ANOVA, and correlation coefficients. A multivariable linear regression model was employed to adjust for or eliminate the effects of confounding factors in the relationship between blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, and opium use. In the regression models, variables with a P-value less than 0.2 (by convention) in the univariate analysis were included as predictors. All predictors were forced into the multivariable linear regression model. IBM SPSS Statistics v22 was used, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

Of 7,428 participants in this study, 2,010 individuals (27.05%) were opium users. The mean age of non-opium and opium users was 46.69 ± 9.14 and 46.39 ± 8.21 years, respectively, which was not statistically significant between the two groups (P = 0.17). Mean fasting blood sugar level was 86.75 and 85.88 mg/dL in non-opium users and opium users, respectively. Mean diastolic blood pressure was 73.18 mmHg in non-opium users; however it was 70.95 mmHg in opium users. The mean systolic blood pressure was 105.20 mmHg in opium users, but it was 107.78 mmHg in non-users. Other demographic and behavioral characteristics of the subjects are detailed in Table 1.

| Variables | Group | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-opium User | Opium User | ||

| Age (y) | 46.69 ± 9.148 | 46.39 ± 8.215 | 0.17 |

| Education (y) | 4.97 ± 3.927 | 5.96 ± 3.745 | 0.000 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.78 ± 4.67 | 23.06 ± 4.36 | 0.000 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73.18 ± 10.920 | 70.95 ± 10.829 | 0.000 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 107.78 ± 15.203 | 105.20 ± 15.123 | 0.000 |

| Physical activity [metabolic equivalent of task (MET)/day] b | 41.26 ± 10.68 | 45.26 ± 14.47 | 0.000 |

| Calorie intake (cal/day) | 2913.35 ± 1115.89 | 3087.38 ± 1194.56 | 0.009 |

| Fasting blood sugar (mg/dL) | 86.757 ± 13.4711 | 85.889 ± 14.3505 | 0.01 |

| Gender | 0.000 | ||

| Male | 1872 (49.0) | 1952 (51.0) | |

| Female | 3546 (98.4) | 58 (1.6) | |

| Marital status | 0.000 | ||

| Single | 282 (84.2) | 53 (15.8) | |

| Married | 4764 (71.1) | 1939 (28.9) | |

| Widow | 307 (97.5) | 8 (2.5) | |

| Separated | 65 (86.7) | 10 (13.3) | |

| Employment | 0.000 | ||

| No | 2960 (93.1) | 221 (6.9) | |

| Yes | 2449 (57.8) | 1787 (42.2) | |

| Alcohol usage | 0.000 | ||

| No | 5392 (74.5) | 1850 (25.5) | |

| Yes | 26 (14.0) | 160 (86.0) | |

| Hookah smoking | 0.001 | ||

| No | 5408 (73.0) | 1997 (27.0) | |

| Yes | 10 (43.5) | 13 (56.5) | |

| Passive smoking | 0.000 | ||

| No | 4955 (84.2) | 929 (15.8) | |

| Yes | 463 (30) | 1081 (70) | |

| Ex-smoking | 0.000 | ||

| No | 5150 (75.0) | 1714 (25.0) | |

| Yes | 268 (47.5) | 296 (52.5) | |

| Cigarette smoking | 0.000 | ||

| No | 4687 (90.3) | 502 (9.7) | |

| Yes | 731 (32.7) | 1506 (67.3) | |

Demographic and Behavioral Characteristics of Study Participants a

As shown in Table 1, the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure and fasting blood sugar levels in opium users are significantly lower than in non-users.

Univariate Analysis shows that diastolic blood pressure was correlated with gender (P = 0.000), opium usage (P = 0.000), hookah smoking (P = 0.009), ex-smokers, passive and active cigarette smoking (P < 0.001), age (P = 0.000), years of education (P = 0.000), BMI (P = 0.000), and calorie intake (P = 0.000).

| Variables | Unstandardized Coefficients (B) | P-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Constant | 57.800 | 0.000 | 55.070 | 60.531 |

| Gender | -3.956 | 0.000 | -4.601 | -4.601 |

| Opium user | -1.838 | 0.000 | -2.559 | -1.117 |

| Hookah smoker | -1.072 | 0.03 | -2.046 | -0.097 |

| Cigarette smoker | -2.346 | 0.000 | -3.352 | -1.339 |

| Ex-smoker | 2.263 | 0.000 | 1.240 | 3.286 |

| Passive smoker | -0.061 | 0.89 | -1.002 | 0.881 |

| Age | 0.152 | 0.000 | 0.119 | 0.184 |

| Education (y) | -0.030 | 0.43 | -0.104 | 0.045 |

| BMI | 0.545 | 0.000 | 0.492 | 0.598 |

| Calorie intake | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

Linear Regression Model for Diastolic Blood Pressure

After adjusting for BMI, cigarette and hookah smoking, and calorie intake, multivariate analysis based on the linear regression model showed that diastolic blood pressure was significantly correlated with opium usage, with an adjusted P-value of 0.000 (Table 2).

Systolic blood pressure was correlated with gender (P = 0.000), employment (P = 0.003), opium usage (P = 0.000), hookah smoking (P = 0.000), ex-smokers, passive and active cigarette smoking (P = 0.000), years of education (P = 0.000), marital status (P = 0.01), energy intake (P = 0.002), age (P = 0.000), and BMI (P = 0.000) in univariate analysis.

In the linear regression model, systolic blood pressure was significantly correlated with opium usage after adjusting for confounders such as BMI, cigarette and hookah smoking, and calorie intake, with an adjusted P-value of 0.002 (Table 3).

| Variables | Unstandardized Coefficients (B) | P-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Constant | 78.435 | 0.000 | 74.158 | 82.711 |

| Gender | -5.726 | 0.000 | -6.769 | -4.683 |

| Has job | -1.376 | 0.002 | -2.256 | -0.496 |

| Opium user | -1.577 | 0.002 | -2.551 | -0.603 |

| Hookah smoker | -0.917 | 0.17 | -2.232 | 0.399 |

| Cigarette smoker | -2.959 | 0.000 | -4.318 | -1.601 |

| Ex-smoker | 2.488 | 0.000 | 1.107 | 3.870 |

| Passive smoker | -0.530 | 0.41 | -1.802 | 0.742 |

| Calorie intake | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| Age | 0.470 | 0.000 | 0.426 | 0.514 |

| Education (y) | -0.045 | 0.38 | -0.145 | 0.056 |

| BMI | 0.752 | 0.000 | 0.680 | 0.824 |

| Marital status | -1.381 | 0.003 | -2.297 | -0.464 |

Linear Regression Model for Systolic Blood Pressure

Factors that correlated with fasting blood sugar (FBS) in univariate analysis included age (P = 0.000), years of education (P = 0.000), BMI (P = 0.000), employment (P = 0.005), alcohol consumption (P = 0.04), opium usage (P = 0.01), hookah smoking (P = 0.04), active cigarette smoking (P < 0.001), passive cigarette smoking (P = 0.008), and marital status (P = 0.003).

In the linear regression model, opium usage was significantly correlated with fasting blood sugar, with an adjusted P-value of 0.016. Adjustments were made for confounders such as employment, smoking, age, and marital status (Table 4).

| Variables | Unstandardized Coefficients (B) | P-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Constant | 64.405 | 0.000 | 61.077 | 67.733 |

| Has job | 0.276 | 0.44 | -0.428 | 0.979 |

| Opium usage | 1.109 | 0.01 | 0.208 | 2.011 |

| Hookah smoking | -0.276 | 0.66 | -1.530 | 0.977 |

| Cigarette smoking | -2.112 | 0.001 | -3.382 | -0.842 |

| Ex-smoking | 1.324 | 0.04 | 0.005 | 2.644 |

| Passive smoking | 0.383 | 0.53 | -0.831 | 1.598 |

| Marital status | 0.023 | 0.95 | -0.849 | 0.895 |

| Age | 0.284 | 0.000 | 0.244 | 0.325 |

Linear Regression Model for Fasting Blood Sugar

5. Discussion

5.1. Results Summary

In this cross-sectional study, 7,428 participants were included, with a mean age of over 46.5 years. More than half were men, nearly 90% were married, and over 50% were employed. Approximately one third of the participants were cigarette smokers, and one fourth were opium users. The mean systolic blood pressure was over 107 mmHg, while the mean diastolic blood pressure exceeded 72 mmHg. The mean FBS was more than 86 mg/dL among the study participants. Our results show that fasting blood glucose was lower in opium users; however, after adjusting for other confounders in the regression model, fasting blood sugar was higher in opium users. Additionally, both diastolic and systolic blood pressures were lower in opium users after adjusting for confounders.

5.2. Comparison with Existing Literature

Azod et al. studied the effect of opium use on blood glucose levels in diabetic patients using medication versus non-medicated patients. They found that opium addiction significantly reduced fasting blood sugar and two-hour postprandial glucose (2HPP) compared with non-addicted patients, but HbA1c levels did not change. This suggests that while opium can cause a temporary drop in blood sugar, it does not affect long-term blood sugar control. While fasting blood sugar and 2HPP were significantly lower in the addicted group, HbA1c did not show significant differences between the two groups (13). Our study was conducted in a large general population without a history of diabetes, and those with diabetes based on self-report and who were taking medication under physician supervision were excluded. Additionally, we did not measure HbA1c, so the correlation between long-term blood sugar control and opium use was not investigated.

A comparison of fasting blood sugar and insulin levels in opium addicts versus non-addicted individuals was conducted in a study by Gozashti et al. This study found that opium consumption could lead to higher FBS and lower blood insulin levels (14). This is consistent with our findings on glucose levels in opium users versus non-users. In contrast, the studies by Masoomi et al. and Sanli et al. showed no significant relationship between opium use and blood glucose levels (15-17). This result contrasts with our findings.

Opium addicts often have a reduced appetite, and due to poor economic conditions, they may decrease their food and calorie intake, which in turn lowers their BMI and blood sugar levels (18, 19). Our results align with these findings in the univariate analysis. However, when BMI and calorie intake were considered as confounding factors, blood sugar levels were higher in opium users. Some studies have shown a decrease in fasting blood insulin in opium users, which contributes to higher fasting blood sugar in these individuals (14). This finding is consistent with our results.

There are controversies in various studies regarding the correlation between blood pressure and opium use. Our results show that both diastolic and systolic blood pressure were lower in opium users. However, Rahimi et al. found that blood pressure was higher in opium users in their study (19). In other studies, no significant difference in blood pressure was observed between opium users and non-users (20-22). On the other hand, Masoomi et al. conducted a study in which they concluded that blood pressure was lower in opium users (16). Opium use can lead to vasodilation through histamine modulation of nitric oxide release and a reduction in sympathetic tone, which may cause a decrease in blood pressure (23). Given these discrepancies, further investigation is needed.

5.3. Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, including an appropriate and large sample size that accounted for multiple confounders. It was a population-based study, but limitations include its focus on rural populations and the cross-sectional design, which does not establish causal relationships. Another limitation is the lack of evaluation of HbA1c, which estimates the average glucose level over the past three months.

5.4. Recommendations

It is recommended to design a cohort study in both urban and rural populations in other provinces to explore the causal relationship between narcotics and blood sugar and blood pressure, considering factors such as dosage and frequency of opium consumption. Additionally, monitoring blood sugar through HbA1c measurement would help assess the effect of opium use on long-term blood sugar management.

5.5. Conclusions

Fasting blood sugar was lower in opium users, but higher in the presence of other confounders. Additionally, both diastolic and systolic blood pressures were lower in opium users. Although opium use is associated with reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure, arbitrary consumption of opium should be discouraged due to its potentially harmful side effects. Based on the results of this study, health policymakers could update the guidelines for managing diabetes and hypertension in individuals who use opium, allowing healthcare providers to make more informed clinical decisions for these patients.