1. Context

From the beginning of history, pregnancy has been considered as an undeniable, natural, and most necessary need that happens millions of times annually (1). Research has been conducted on the different issues and dangers that affect pregnancy; one such issue is anemia (2).

Anemia is a common, global health problem that has short-term and long-term effects during pregnancy (3). Generally, anemia is observed in poor countries. It has a significant impact on issues such as placental abruption, preeclampsia, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), low birth weight, and fetal or maternal fatality (4, 5).

Anemia often becomes more severe in the presence of other chronic diseases such as Helicobacter pylori, malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, and diabetes. Without treatment, anemia can cause an increase in fetal and maternal mortality rates (6-8). Recent studies have shown that anemia is responsible for 15% - 20% of maternal deaths (5).

In a systematic review with a sample size of 11,037, Esmat et al. (2010) reported the highest and the lowest prevalence of anemia among pregnant Iranian women to be 21.5% and 4.3%, respectively and the average prevalence as 12.4% (based on the definition provided by the WHO [hemoglobin < 11 gr/dL]) (9). Several studies have investigated the prevalence of anemia among pregnant Iranian women in the last 10 years (2005 - 2015) (10-27). However, no systematic review or meta-analysis has been conducted in the mentioned period. Accordingly, the present systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the prevalence of anemia among pregnant Iranian women in the last 10 years (2005 - 2015) and compare this prevalence with that of the years before 2005.

2. Evidence Acquisition

The current study was performed in several stages: determination of the subject, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of the results. The Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist was used during the study (28). To avoid biases, all processes of collection and selection of studies, quality assessment, and data extraction were performed by two independent researchers.

2.1. Data Sources

The present systematic review was performed to estimate the prevalence of anemia among pregnant Iranian women during the period of 2005-2015. Searches for relevant studies conducted between January 1st, 2005 and December 31st, 2015 were done through databases such as the Iranian journal database (Magiran), Iranian biomedical journals (IranMedex), the Scientific Information Database (SID), global medical article Limberly (Medlib), IranDoc, Scopus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, Springer, Web of Science, Wiley Online Library, and Google scholar.

The searches were conducted using both Persian and English keywords including: "Prevalence", "Anemia", "Hemoglobin", "Ferritin", "Pregnancy", "Pregnant Woman", "Prenatal care" and "Complications of pregnancy". A combination of AND/OR operators were used in the searches. In order to locate more studies, the references of all relevant articles were reviewed.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The main inclusion criterion for this study was a reference to the prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women and the exclusion criteria included: 1, Studies in which a non-random sampling method was used; 2, studies without specific sample origins; and 3, studies of a repetitive nature.

In this study, anemia is defined based on the definition provided by the WHO (hemoglobin < 11 mg/dL) (29). When the full text was not available, an email request for the whole article was sent to the author.

2.3. Quality Assessment

After finding all relevant articles, the selected ones were evaluated by researchers based on the STROBE checklist (30). The 22-item STROBE checklist assesses a wide range of methodological issues including sampling methods, measurement of parameters, statistical analysis, adjustment for confounding factors, reliability and validity of research instruments, and research objectives. Each question of the checklist has a score between 0 and 2 points and the maximum attainable number of points was 44. The articles considered in this study were categorized into three classes of low (0 - 15 points), medium (16 - 30 points), and high (31 - 44 points) quality. Finally, all relevant articles that attained a minimum score of 16 were included in the meta-analysis.

2.4. Study Selection

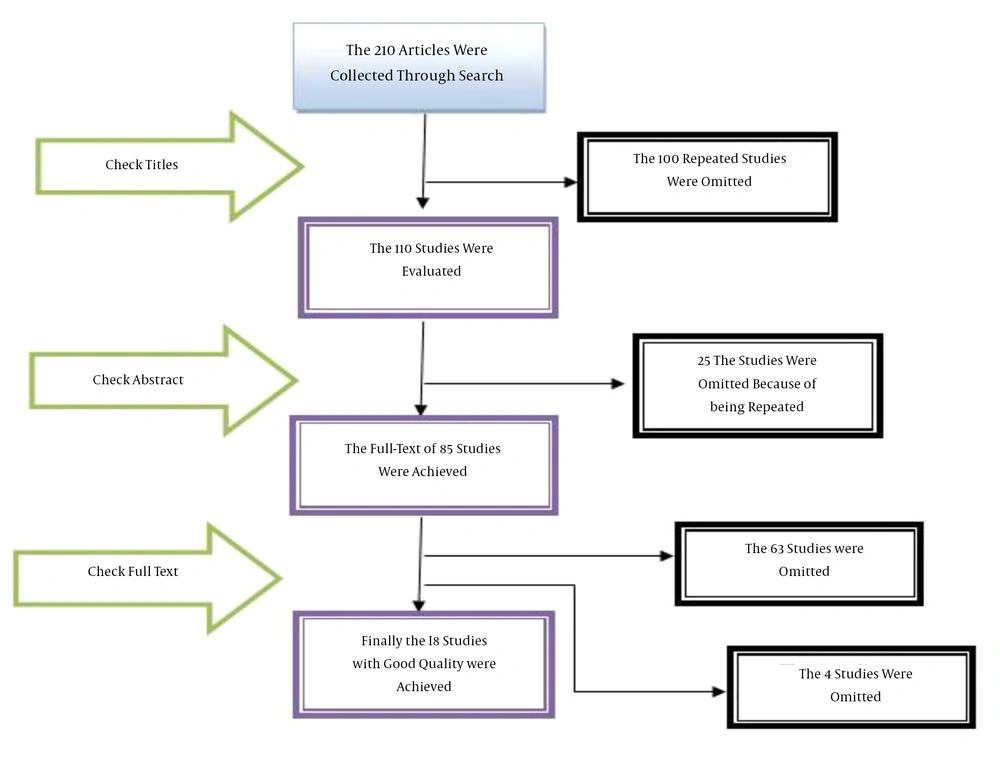

In the first stage, 210 articles related to the prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women were found. Of the initial 210 articles, 100 replication articles were excluded from the study (replication studies are those extracted by both researchers; they have similar titles, authors, and content and are published in the same journal). The abstracts of all 110 remaining articles were evaluated; however, 25 articles were excluded from the study due to irrelevancy.

In the second stage, the full texts of the remaining 85 articles were examined. Of those 85, 62 articles were excluded due to: 1, irrelevant topics; 2, using a random sampling method; 3, lack of a standard framework for the evaluation of anemia incidence; and 4, not conducted in the period of 2005 - 2015. The remaining 23 articles were entered into the quality assessment stage, during which 5 more articles were excluded due to low quality. The final 18 articles were examined through the process of meta-analysis (Figure 1).

2.5. Data Extraction

Using a pre-prepared checklist, all 18 articles were arranged for the data extraction stage. The checklist included author’s name, year of study, place of study, type of study, sample size, average age, gestational age, cut-off point for hemoglobin, prevalence of anemia, and rural/urban samples.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The random effects model was used for meta-analysis of the combined results of the studies. The variance for each study was calculated using the instead of binominal formula. The presence of heterogeneity was determined by the DerSimonian and Laird (DL) approach (28). The significance level was < 0.1, and the I2 index was used for estimates of inconsistency within the meta-analyses. The I2 index estimates the percent of observed between-study variability that is due to heterogeneity rather than to chance and ranges from 0 to 100 percent (values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered as representing low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively) (31, 32).

A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity while a value of 100% indicates significant heterogeneity. For this review, we determined that I2 values above 75% were indicative of significant heterogeneity, warranting analysis with a random effect model as opposed to the fixed effect model to adjust for the observed variability. Meta-regression was introduced to explore and explain heterogeneity between studies in a meta-analysis. The analysis among the sub-groups was carried out regarding the specific region (North, South, West, East, and Central) and whether the area was rural or urban.

Data manipulation and statistical analyses were done using STATA software, version 11.2. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Due to the type of study and the checklist parameters considered in the quality assessment stage, determination of publication bias and presentation of funnel plots were not necessary (33, 34)

3. Results

During the initial search, a total of 210 relevant articles were found. After exclusion of articles according to the previously described criteria, 18 papers published between the years 2005 and 2015 were selected for analysis (Figure 1).

The combined sample size of pregnant Iranian women was 51,521 with an average age of 26.17 years (CI: 95%; 22.6 - 29.68). General specifications for each sample are presented in Table 1.

| Author Name | Place of Study | The Population Under Review | Year of Study | Sample Size | Trimester of Pregnancy | The Mean Age, y | Prevalence of Anemia, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirzaie et al. (10) | Kerman | not defined | 2005 | 2213 | 1,2 and 3 | 26.82 | 4.7 |

| Veghari et al.(11) | Gorgan | Rural | 2007 | 48 | 25.8 | ||

| Faraji et al.(12) | Rasht | Urban | 2008 | 555 | 1 | 23.3 | 21.3 |

| Ranaei et al.(13) | Sanandaj | Urban | 2009 | 1137 | 1 | 8 | |

| Soofizadeh et al.(14) | Sanandaj | Rural | 2009 | 1500 | 1 | 28.4 | 7.1 |

| Akbarzadeh et al.(15) | Shiraz | Rural | 2009 | 89 | 1,2 and 3 | 25.74 | 29.2 |

| Sadeghian et al.(16) | Tabriz | Rural | 2010 | 34 | 1 | 32.65 | 5.9 |

| Mostajeran et al.(17) | Isfahan | Urban and rural | 2010 | 7233 | 9.4 | ||

| Rahbar et al.(18) | Semnan | not defined | 2010 | 546 | 1 | 25.6 | 32.1 |

| Pasdar et al.(19) | Kermanshah | not defined | 2010 | 32450 | 1,2 and 3 | 3.6 | |

| Sharifi et al.(20) | Shiraz | Urban and rural | 2011 | 400 | 3 | 12.3 | |

| Alizadeh et al.(21) | Ardebil | not defined | 2011 | 312 | 3 | 16:37 | 23.2 |

| Riahinejad et al.(22) | Esfahan | Urban | 2012 | 280 | 1,2 and 3 | 26.2 | 46 |

| Jafari et al.(23) | Bushehr | Urban | 2015 | 250 | 1,2 and 3 | 27.2 | 21.8 |

| Saberi et al.(24) | Mashhad | not defined | 2015 | 504 | 1,2 and 3 | 27.8 | 23 |

| Eslami et al.(25) | Six provinces | Urban and rural | 2015 | 2993 | 3 | 26.82 | 21.6 |

| Parashi et al.(26) | Tehran | Urban | 2010 | 168 | 1 | 27.5 | 31 |

| Yazdani et al.(27) | Babol | not defined | 2010 | 809 | 1,2 and 3 | 26.9 | 14.4 |

Detailed Characteristics of 18 Articles Included in the Systematic Review on the Prevalence of Anemia Among Pregnant Iranian Women

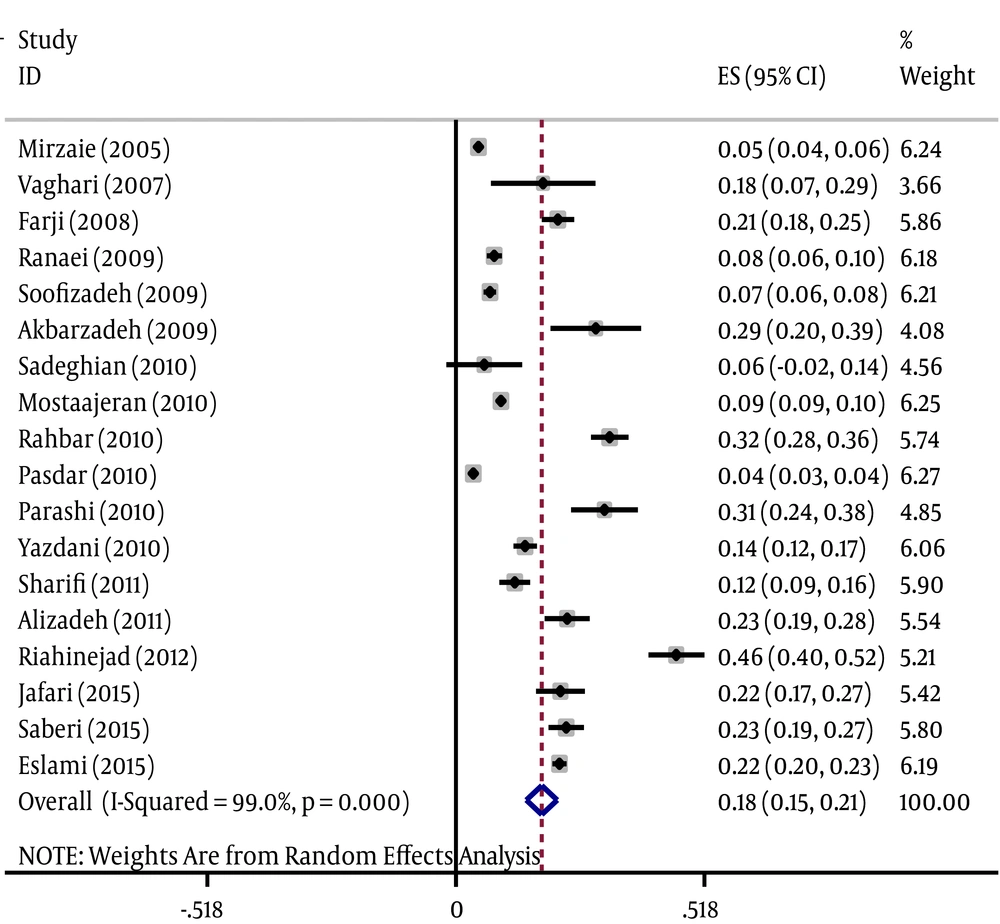

Between 2005 and 2015, the prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women has been 17.9% (CI: 95%; 14.7 - 21.1). The lowest prevalence (3.6%) was reported in a study conducted in Kermanshah in 2010 and the highest prevalence (46%) was reported in another study performed in Esfahan in 2012 (Figure 3).

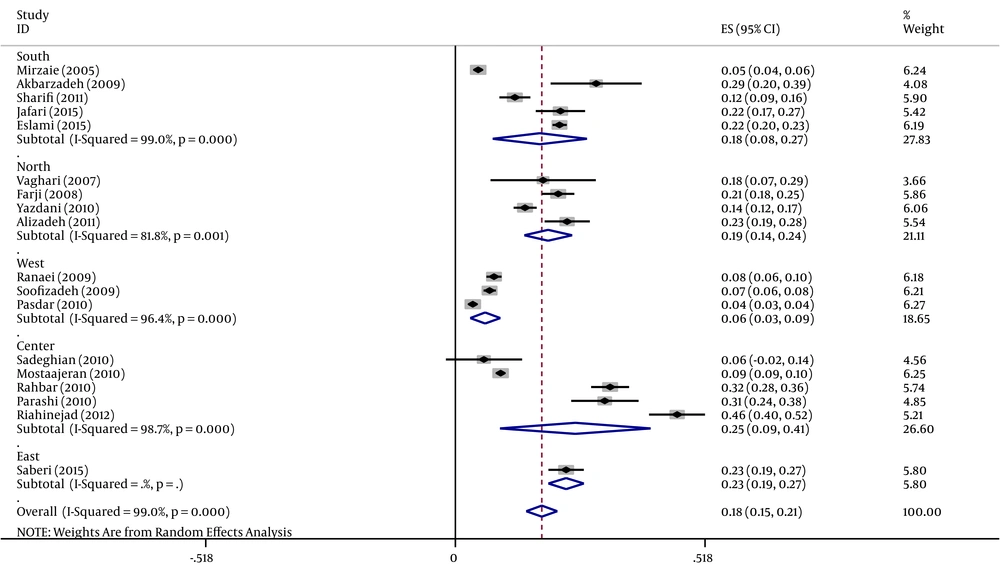

Geographically, the prevalence of anemia among pregnant Iranian women is presented in Figure 3. The highest and the lowest prevalence of anemia were in Iran’s western (6.3%) and central (24.9%) regions.

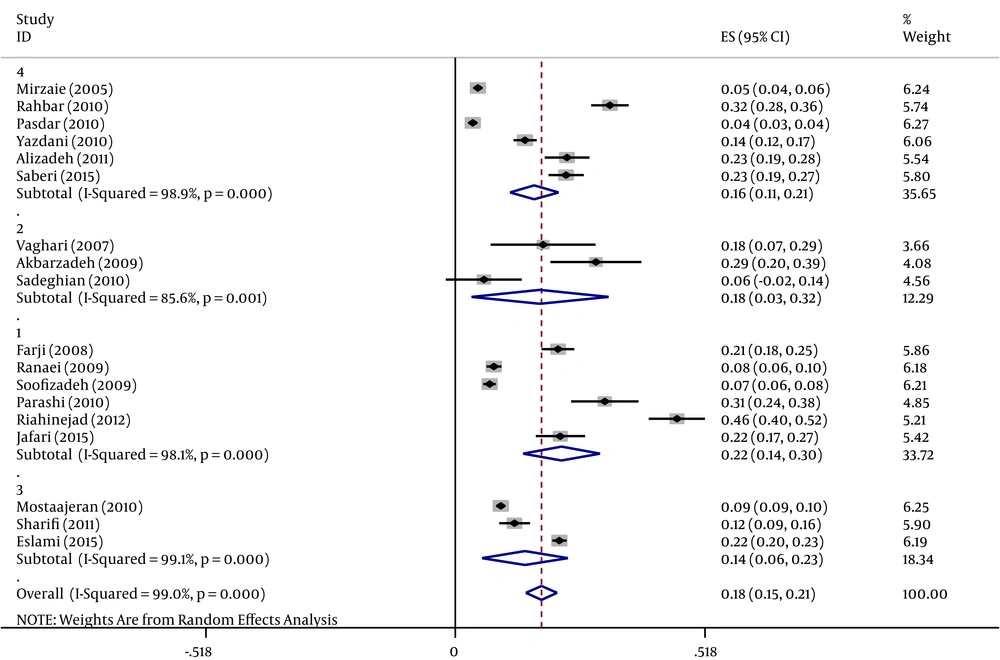

The prevalence of anemia among rural and urban pregnant Iranian women were 17.6% (CI: 95%; 3.31 - 7.31) and 22.1% (CI: 95%; 14 - 30.1), respectively (Figure 4).

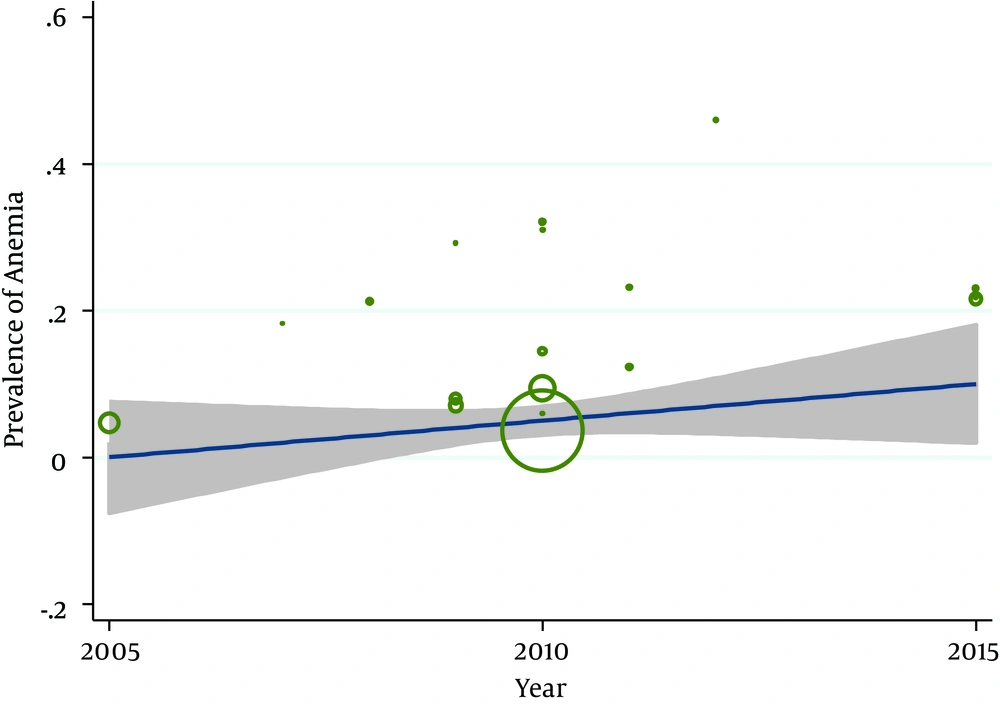

To determine the relationship between the prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women and the period in which the examined studies were conducted, a meta-regression analysis was conducted; however, the calculated P-value (0.136) was not statistically significant (Figure 5).

4. Discussion

This study is the only systematic review and meta-analysis study on the prevalence of anemia among pregnant Iranian women in the period 2005 to 2015. Studies have reported variable prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women living in different geographical regions which might be due to the differences in geographical issues, lifestyles, and daily diet (12, 13, 17). In this study, the prevalence of anemia was evaluated based on the three factors of geography, rural/urban living, and year of study. The overall prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women was 17.9%.

The most common cause of anemia in pregnant women is iron deficiency 95% of cases are caused by lack of iron in the diet and the unethical use of iron compounds (35, 36). Therefore, the prevalence of anemia can be reduced through interventions such as training in proper nutrition and the use of iron and folic acid supplements (37).

This study has estimated the prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women from 2005 to 2015 to be 17.9%. According to the WHO (30) 5% - 19.9% is the range in which the prevalence of anemia can be considered a mild health problem in a country, placing Iran in this group. The WHO reports the prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women to be estimated at 40% (29), which is inconsistent with the results of this study. The reduction of the prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women could be due to the use of iron and folic acid supplements at health centers and also a national program to enrich flour with iron and folic acid (37).

The results of this study show an increase in the prevalence of anemia compared to a previous systematic review study conducted in Iran between 1993 and 2005 which reported the prevalence as 12.4% (9). The cause of this increase in recent years could be inappropriate nutrition or unethical use of iron and folic acid supplements by pregnant mothers.

Clinical trials have indicated the effectiveness of iron supplements in improving hemoglobin concentration during pregnancy (38, 39). In their review study, Haider et al. (2012) also showed that the use of iron supplements during pregnancy increases children’s birth weight (40). Therefore, it seems that the most effective intervention to reduce the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women is educating them in the proper use of iron and folic acid supplements.

The reported prevalence of anemia in other parts of the world such as Egypt (26%), Africa (31% - 52%), and Central and Eastern Europe (14.40%) is also varied (41, 42). These different rates in different parts of the world can reflect social and economic issues along with the frequency of iron use and the incidence of parasitic and infectious diseases (43).

Geographically, the highest and lowest prevalence of anemia were observed in the central zone of Iran (24.9%) and the western zone (6.3%), respectively. This could be explained by the existing differences in the residents’ lifestyles and daily diet. In the aforementioned systematic review of studies conducted between 1993 and 2005, no geographical analysis was performed; thus, in this study, the rates of prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women before and after 2005 could not be compared based on geographical regions.

In regards to sample size and geographical region covered, the most comprehensive study on the prevalence of anemia among pregnant Iranian women was performed by Eslami et al. in 2015 (25). They conducted their study on 2,993 pregnant Iranian women living in six provinces of Iran and reported an overall prevalence of 21.6%, which is in line with the present study’s results.

In this meta-analysis, the prevalence of anemia among rural pregnant women (17.6%) was lower than that of urban pregnant women (22.1%); this could be due to differences in lifestyle and daily diet.

The limitations of the present study include: 1, the researcher could not search the combination of keywords in Iranian databases; and 2, some related articles and medical theses were excluded from the analysis due to either low quality or lack of a standard framework for the evaluation of anemia incidence.

4.1. Conclusion

The current study shows that the prevalence of anemia in pregnant Iranian women in the last 10 years was lower than the WHO’s statistics for developing countries. However, the prevalence has increased rather than decreased in the past decade. Therefore, appropriate intervention plans, including training in proper nutrition during pregnancy and training in the correct use of iron, vitamins, and folic acid supplements, should be arranged and performed in prenatal clinics or before marriage.

In order to address this issue, a systematic and meta-analysis review study cannot replace a national study. It is advised that for an accurate estimation of the current prevalence of anemia and its related factors in any region of Iran a national study should be designed and performed.