1. Context

Currently, one of the main problems with public policies and healthcare assessment is the lack of valid information on the performance and quality of healthcare service provision (1). The most pressing consequence of this problem is that there is little reliable information available on the quality of healthcare providers, but such information is needed to guide public and individual choices (1, 2). Thus, improving competition and efficiency in the area of healthcare is a focal issue in current reforms to medical financing and health plan choices (3). Although these reforms are clearly influenced by cost and clinical expenses, quality is increasingly a matter for concern (4). Using performance indicators and assessing outcomes are among the methods that can be used to measure and monitor the quality of care and service provision (5-8); also, developing and reporting indicators have led to quality improvements in many countries. A number of studies focus on the design and implementation of such indicators in healthcare systems (6, 9-14). There are many reasons for the problem of qualitative information. First, measurement and evaluation are problematic because the collection of relevant information (often based on the long-term outcome of the patient) is difficult for health service providers. Second, even if the information is relevant and appropriate, its multidimensional nature leads to other issues (15, 16). Specifically, clinical care quality encompasses a number of different outcomes, including service and care processing, and all of these factors are involved in quality assessment (17). The third obstacle in assessing the quality of healthcare is the limited number of patients for studies and the effects of a large number of factors other than provider quality on measuring the quality of the health services delivered by any one provider (17). Last, orientation and prejudice are issues that may change how patients are treated and, in turn, may affect healthcare providers’ results. Typically, trends are the result of systematic differences between patients (18). All of these issues have constrained the value of explicit information in relation to quality of healthcare, particularly significant health outcomes (18-20). Unfortunately there is no published study available that assesses the state of the quality of healthcare providers’ performance, because no globally confirmed indicators have been defined for evaluating healthcare providers’ performance (21). In fact, it seems that the best way to assess providers’ performance is to investigate the effects of their healthcare services on clinical outcomes and patients’ satisfaction with the services (22). In this regard, each country has tried to design and implement indicators that correspond to its own conditions. Evidently, drawing on the experience and indicators used by other countries is helpful in meeting the above goal, and in this sense, a summary of all published indicators may be very helpful. It is evident that using the indicators developed by other countries and their experiences of those indicators will help us to implement our objectives here. To facilitate this, the current paper will contain a list of the indicators published in other countries. In this systematic review, we describe all studies relating to issues with providers’ delivery of quality healthcare by employing indicators of the quality of healthcare services.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Study Population and Data Collection

Systematic review procedures have already been considered and published in the international protocol (Prospero). The studies were identified via a search of numerous electronic databases, including Cochrane Library, PubMed, Scopus, Ovid (Medline), the Social Sciences Citation Index, SID (scientific information database, or Persian database), and Iran Medex (Persian database). Information was also obtained by scanning reference lists for the articles included, and through consultations with experts in the field.

Our sample was based on data from January 1971 to May 2015. Only manuscripts in English and Persian with available full texts were reviewed. The reviewed articles included cross-sectional, descriptive, qualitative, and systematic review studies. Conference presentations, case reports, and intervention studies were excluded from the review process.

The key words searched individually and in combination included the following: health, healthcare, health care, provider, effectiveness, quality, clinical outcome, patient satisfaction, and quality of life.

The articles were evaluated by two reviewers based on the STROBE checklist (23), the CASP checklist for qualitative studies (24), and the PRISMA checklist (25). Also, the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool was used to evaluate the risk of bias associated with individual studies (26).

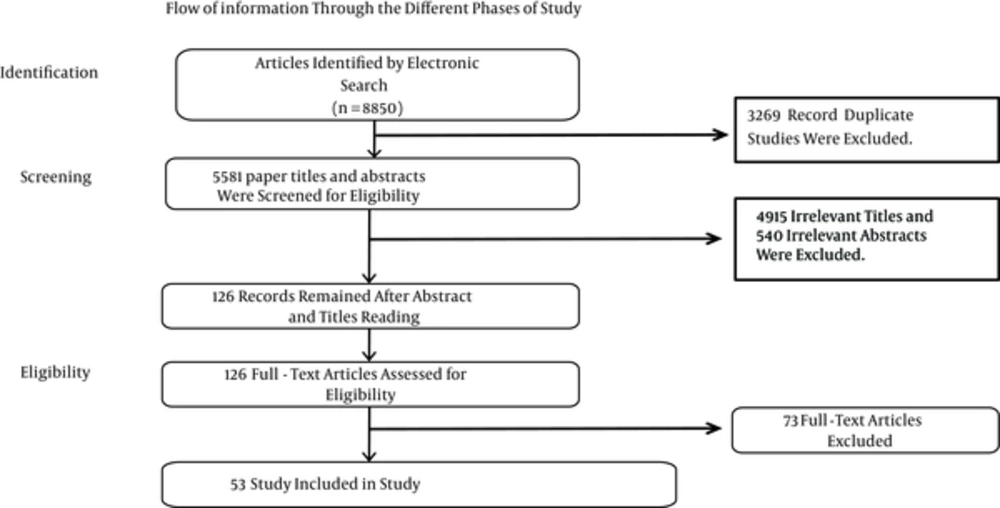

The following data were extracted from each article: the country, the conditions studied, the study design and sample descriptions (patients and general physicians), the date of data collection, the measured criteria, and the standards used to judge the quality and results. Along with the reviewer, two referees independently examined the identified studies and articles based on the article title and abstract in terms of the qualification and eligibility of each paper. Selected full-text articles were reviewed and evaluated independently by the two referees. The population providing healthcare services was regarded as the main criterion, with no restrictions on the category of service provider job (for example, doctors, nurses, etc.), the level of services provided (for example, primary care or hospital care), or the target population for those services. In this study, a meta-analysis was not possible due to inconsistencies in the results of previous studies and their different methodologies. Hence, the scholars had to calculate the mean score of improvements statistically and present them in descriptive terms. Of the 8,850 articles identified by the abovementioned key words, 53 studies met the study criteria and were reviewed (Figure 1).

2.2. Criteria for Quality and Safety of Healthcare Providers

According to the primary review and the content analysis of the results, the quality of healthcare was evaluated based on three criteria (27-31). The first is “patient satisfaction,” which refers to the relationship between a physician or another healthcare professional and a patient. This includes interpersonal processes such as the provision of information and emotional support, and the involvement of patients in making decisions based on their preferences (29). The second criterion is “clinical outcomes,” which refers to a patient’s health status or a change in a patient’s health status, such as an improvement in symptoms or mobility resulting from medical care received. This includes both intended outcomes such as the relief of pain, and unintended outcomes such as mortality or other complications (5). The third criterion is “quality of life,” which refers to a patient’s health-related quality of life as assessed using various tools. Thus, patients’ satisfaction with healthcare services, observed improvements in their clinical outcomes as recorded in hospital files, and evaluation of their quality of life (if available) were included in the sources of data collected (32).

3. Results

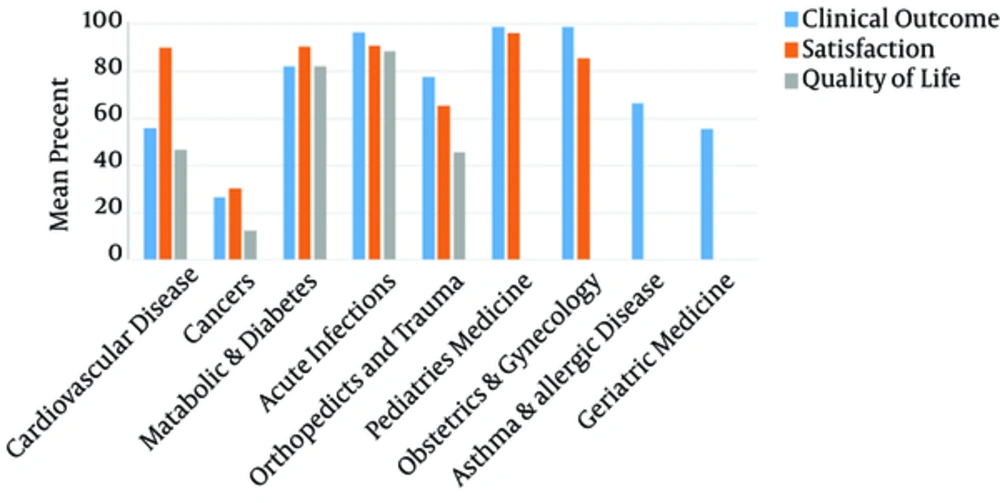

Since we were unable to find studies titled “quality of healthcare provider performance,” we had to take “healthcare quality” indicators into account as an assessment of healthcare performance quality. These indicators are described in the method section. The improvements in the indicators in terms of patient satisfaction, health outcomes, and quality of life were considered the end points for measuring the quality of healthcare performance. Concerning the composition of papers according to the studied conditions, of the 53 study papers, 18 evaluated the quality of care provided for cardiovascular disorders (33-50) and 12 evaluated cancer conditions (51-62). Eight assessed metabolic disorders and diabetes (63-70), six assessed acute infections (71-76), three assessed orthopedic and trauma conditions (77-79), two assessed pediatric conditions (80, 81), two assessed obstetric and gynecological conditions (82, 83), one assessed asthma and allergic diseases (84), and one assessed geriatric conditions (85). The majority of the studies (51 in 53 articles) were carried out in high-income countries. Also, 32 of the papers were published in the United States. Twenty seven of the articles (51.0%) were simple and descriptive, 17 were cross-sectional studies (32.0%), three were systematic reviews (5.7%), and six were qualitative studies (11.3%). With regard to the strategy employed in the studies, 28 (52.8%) followed random sampling, and in 25 (47.2%), sampling was based on the self-selection method. Regarding the number of procedures reviewed, seven papers had less than 50 (13.2%), 14 papers had between 50 and 100 (26.4%), 26 had between 101 and 500 (49.1%), and only six had more than 500 (11.3%). The major indicators of healthcare quality were patients’ level of satisfaction in 11 papers (20.8%), improvements observed in clinical outcomes in 53 papers (100%), and patients’ quality of life in nine papers (17.0%). The assessment of improvements in healthcare providers’ performance (based on healthcare quality) (Table 1) indicated that improvements in clinical outcomes ranged from 26.6% in cancer conditions to 98.8% in both pediatric and gynecological conditions, and an acceptable level of patient satisfaction was achieved in the range of 30.2% for cancer conditions to 96.0% for pediatric conditions. Also, improvements in quality of life ranged from 12.5% for cancer conditions to 88.7% for acute infections.

| Condition Studied/Number of Subgroups | Criterion | Rate of Improvement, % | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | 18 | ||

| 18 | Clinical outcome | 55.9 | |

| 4 | Satisfaction | 89.9 | |

| 4 | Quality of life | 46.6 | |

| Cancers | 12 | ||

| 12 | Clinical outcome | 26.6 | |

| 2 | Satisfaction | 30.2 | |

| 2 | Quality of life | 12.5 | |

| Metabolic diseases and diabetes | 8 | ||

| 8 | Clinical outcome | 82.2 | |

| 1 | Satisfaction | 90.5 | |

| 1 | Quality of life | 82.2 | |

| Acute infections | 6 | ||

| 6 | Clinical outcome | 96.6 | |

| 1 | Satisfaction | 90.8 | |

| 1 | Quality of life | 88.7 | |

| Orthopedics and trauma | 3 | ||

| 3 | Clinical outcome | 77.4 | |

| 1 | Satisfaction | 65.2 | |

| 1 | Quality of life | 45.6 | |

| Pediatric medicine | 2 | ||

| 2 | Clinical outcome | 98.8 | |

| 1 | Satisfaction | 96.0 | |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 2 | ||

| 2 | Clinical outcome | 98.8 | |

| 1 | Satisfaction | 85.6 | |

| Asthma and allergic diseases | 1 | ||

| 1 | Clinical outcome | 66.5 | |

| Geriatric medicine | 1 | ||

| 1 | Clinical outcome | 55.6 |

Improvements in Healthcare Provider Performance (Based on Healthcare Quality)

According to the results, healthcare systems for obstetrics and gynecology and pediatric medicine show the highest rate of improvement in clinical outcomes with 98.8%, while acute infection stands in second place with 96.6%. By contrast, healthcare systems for cancer conditions show the minimum rate of improvement in clinical outcomes with a mean of 26.6%; this result may be attributable to a lack of definitive treatment methods for cancers. Clinical outcomes for metabolic diseases and diabetes, orthopedic conditions, trauma, asthma and allergic diseases, geriatric diseases, and cardiovascular diseases show the next highest rate of improvement, with 82.2%, 77.4%, 66.5%, 55.9%, 55.6%, and 26.6%, respectively. As well as clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction had the highest rate of improvement for pediatric medical healthcare, with a rate of 96%. Acute infections, metabolic conditions and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obstetrics and gynecology, orthopedics and trauma, and cancers come next with 90.8%, 90.5%, 89.9%, 85.6%, 65.2%, and 30.2%, respectively. From the above results, it can be concluded that the clinical outcomes for obstetrics and gynecology, pediatric medicine, and acute infections are of the best quality compared to healthcare in other areas. By contrast, cancers have the lowest healthcare quality of all healthcare services (Figure 2).

4. Conclusions

Based on this review, there is no effective indicator for properly assessing healthcare providers’ performance and their role in improving the quality of healthcare services. Based on three different healthcare indicators, namely, clinical outcome, patient satisfaction, and patient quality of life, and taking account of patients’ statements and medical record descriptions, it was found that in most clinical conditions, proper healthcare services led to considerable improvements in patients’ outcomes, satisfaction, and quality of life. This was especially the case in some fields, such as pediatrics and gynecology. However, unfavorable outcomes were also found, and decreased satisfaction were an issue in some cases, for example, cancer. In general, we consider the abovementioned indicators to be the most relevant for assessing the quality of healthcare providers’ performance.

In any study or rating of the quality of healthcare provision, defining parameters to measure the quality of healthcare services is the main problem. The quality of healthcare providers’ services can be rated using several parameters. For example, Bailit et al. state that for obstetrics and gynecology, the risk-adjusted primary cesarean delivery rate is a good marker of maternal and neonatal outcomes (82). Also, there is a very important need for such information when it comes to planning public health policies, and Cardemil et al. (2012) showed that individuals planning community health worker assessments as part of community case management can use these results to make an informed choice of methods on the basis of their own objectives and the local context (80). This information can even be used by other countries to plan healthcare programs for the future, and Santana and Stelfox (2012) showed that their findings regarding the quality indicators used by trauma centers to measure performance could be useful for countries with similar systems of trauma care (79).

Schuster et al. (86) and Sawyer et al. (87) examined a large number of studies and concluded that only 50% of the patients had received advise on preventive care, while 70% had received the recommended acute disease care, and 20% had received the recommended acute contraindicated care. McGlynn et al. (88) and Min et al. (89) concluded that only 55% of their study participants received the recommended care, and in addition, many patients in their study did not receive high-quality healthcare; in other words, it seemed that many patients were not satisfied with the performance of their healthcare providers. In general, the close relationship between the quality of healthcare services and the performance of health service providers is undeniable (90). Studies indicate that when healthcare administrators, healthcare providers, patients, and parents cooperate collaboratively, healthcare quality and safety, as well as the patients’ and service providers’ satisfaction, increase, and costs are reduced (91). In addition, the main parties responsible for improvements in healthcare provider quality vary. A service provider may comprise an organization, a team, or simply an individual health worker (90). However, while all are ideally committed to the broad goals of a quality policy in a general system, their main concern is ensuring that the services they offer are of the highest possible standard and meet the needs of individual users, families, and the community. The results of improved quality in health service provision are not restricted merely to the providers of care or to health services (92).

Another point that should be considered in evaluating the role of healthcare providers is access to high-quality services. Interpersonal communication between service providers and customers is very effective in high-quality healthcare services. This type of communication is one of the most important components of improving customer satisfaction and compliance, and enhancing clinical outcomes (93). Patients who understand the nature of their own illness believe that their service provider is concerned about their health and are more satisfied with the services they receive. As a consequence, they are more likely to engage with the healthcare system. In this context, consideration of several factors, for example, effective interpersonal communication, is necessary (93).

It can be concluded that the greatest effect of improvements in healthcare service provision was observed in pediatrics and gynecology, while the least improvement was found in cancer conditions. In this regard, the results may be affected by some strong confounders such as the development status of the country, the suitability of the indicators used for assessing the quality of healthcare providers, the type of study, the number of procedures, and the time of the quality assessment. More importantly, the nature of clinical conditions can be a major factor affecting clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and patient quality of life Therefore, the naturally poor outcome with regard to cancer conditions explains a low satisfaction level with the related healthcare providers.

4.1. Study Limitations

This study was limited to articles published in English and Persian. Other restrictions include the number of databases searched and the limited number of indexes available on health and medical care quality. Thus, it is suggested that future studies be conducted using more databases, other languages, and possible also other indicators.