1. Background

Fathers’ adaptation interactions impact the wellness and health of children (1). A father’s primary adaptation will facilitate the transition into fatherhood and strengthen the bonding and attachment between the father and his children (2). Father adaptation being constructed build numerous situations for fathers to respond to their duty to their children (3). Fathers more involved can be good for their offspring (4).

A number of young fathers enter fatherhood without the fathers’ adaptation (5). The critical time for fathers’ adaptation in first-time fathers is his wife’s pregnancy (2). At this time fathers begin to seriously think about the challenge of fatherhood and their lifestyle (6). Fatherhood programs need to start in the antenatal period and continue throughout the first few years of the child’s life (7). In the antenatal period, the father’s motivation is high in regards to the father’s education programming (8). This gives an opportunity to start an effective relationship with fathers, which reinforces their involvement (2).

The putative duty of the father has almost always been viewed as a breadwinner duty (9). However, today, compared to 3 decades ago, the duty and practices of fathers have changed (1). The ideals and practices of fatherhood are more contested as well as variable, and are undergoing greater transition than those pertaining to motherhood (5). Research points to the fact that fathers are also stepping beyond their traditional roles to contribute in child care and child rearing (10). On the other hand, responsible fathers play a vital role in their children’s development (2). For this reason, in recent years the father’s participation and involvement has been emphasized (11).

Father’s motivation has a key influence on the father’s adaptation (5). Other recent research showed that the diversity of conditions, including social, cultural, ecological, and economic factors impact the adaptation of the father (12). Health providers have important roles to play in influencing and facilitating the father’s adaptation. Furthermore, it encourages them to educate themselves about their important roles on the emotional well-being of their children (13). Fathers need to understand the important role of helping to improve a child’s self-confidence (1). Fathers also need to understand that building self-esteem and self-confidence is important to grow up in the child (3). Evidence has accumulated demonstrating that father’s adaptation is important for fatherhood (2, 7, 11, 12).

In order to learn the importance of the role of the father’s adaptation in fatherhood and the healthy development of children it is essential to review the role of affective factors in father’s adaptation of healthy children. The aim of the current study was to provide a clear overview of the existing evidence on the effective factors on the father’s adaptation.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Sources

The protocol of this systematic review has been developed based on “Preferred Reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” (PRISMA-P). According the protocol of systematic literature reviews, search strategies included: searches in electronic databases, reference list, journal hand, gray literature searches, stakeholder inquiry, and related books. This review was based on an extensive search in the electronic databases, which included: ISI Web of Science, MEDLINE, CINAHL, HMIC, Child Data, NCJRS, HSRProj, IBSS, Magiran, Iran Medex, Iran Doc, SID (Scientific Information Database), and Google Scholar. The terms “Father”, “Paternal behaviors”, “Behavior”, “Paternal”, “Father-child relationship”, “Father-child relation”, “Adaptation”, “Care”, and “Child” were used to search the databases.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Research was included in this review if: focused on Fatherhood and Father’s adaptation, they were scientific papers with the quantitative or qualitative method, providing appropriate and suitable information about effective factors on the father’s adaptation of healthy children, published in a scientific and high-quality scholarly journal, and they had been published between August 1990 and September 2017. Studies were excluded from this review if: they didn’t relate to the articles or they didn’t report the specific results of father’s adaptation. All included studies were screened independently by 2 authors using a checklists. Reviewers excluded low qualified studies on the STROBE and CASP checklist. STROBE checklist was used for quantitative study, whereas a CASP tool was developed for qualitative study. STROBE checklist is an assessment tool for reporting quality. This checklist was derived from cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies (11). In addition, CASP (14) has been developed for those unfamiliar with qualitative research and its theoretical perspectives. This tool presents a number of questions that deal very broadly with some of the principles or assumptions that characterize qualitative research (Table 1).

| Study Design | Appraisal Checklists |

|---|---|

| Quantitative study (n = 8) | STROBE |

| Qualitative study (n = 13) | CASP |

Included Studies and Appraisal Checklists

The main information is extracted from the studies by the reviewers, name of authors, published years, sample size, data collection strategy, study population, setting, reliability and validity of the tool, study objectives and findings, STROBE, and CASP score.

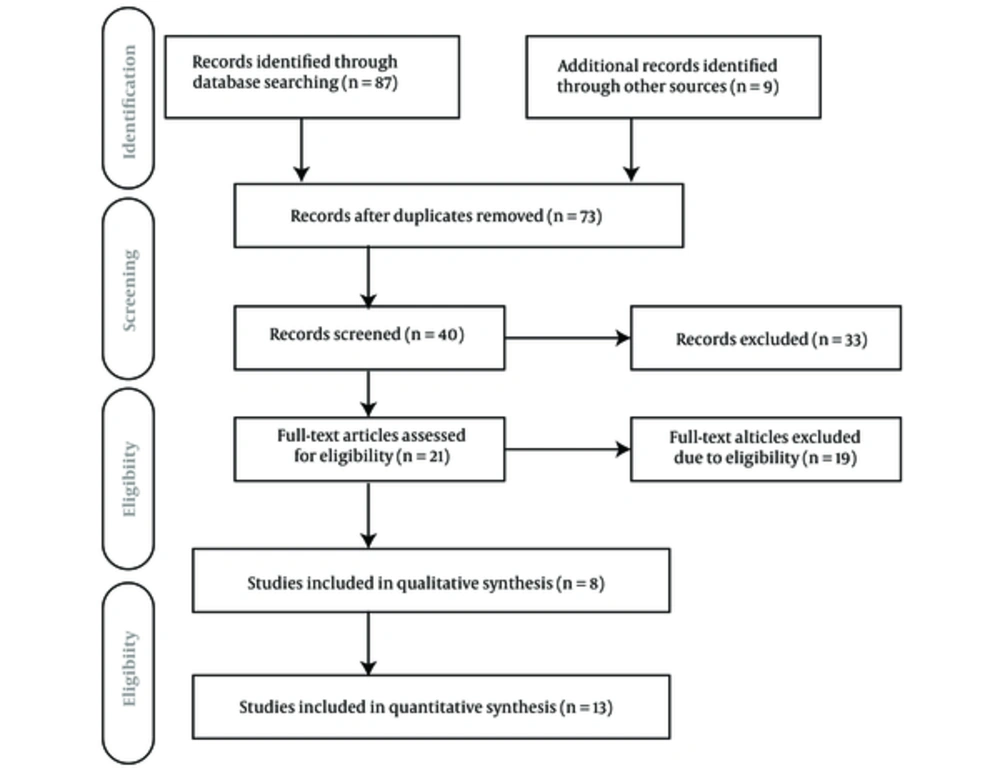

All duplicates records were identified and removed. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Then, reasons removed study record. According to the inclusion criteria, 96 documents were selected, 56 documents were excluded due to duplicate articles, and 40 remained; in the after step, 19 articles were excluded due to eligibility, and finally, 21 papers remained (Figure 1).

3. Results

The 21 document was included in the current study from an initial search of 87 records. In total, 13of the studies were conducted using a qualitative method and the remaining 8 of the studies had a quantitative method included: descriptive, cross-sectional, and cohort studies. Data collection method in qualitative studies was focus groups discussion and interviews, however, the data collection method used to collect data in all quantitative research study was a questionnaire.

The final synthesis was conducted on 21 articles with the eligibility criteria. The results obtained from relevant articles can be divided into 3 general groups of effective factors in father’s adaptation, including: paternal factors, child factors, and health care service factors.

The most important paternal factors affecting contains: age, occupation, educational level, health insurance, physical, emotional, culture, anxiety, psychological distress, satisfaction with marriage, coping strategies with stress, life events, socio-economic disadvantage, financial preparation, self-efficacy, satisfaction in fatherhood alternating between work and home, experiences of antenatal, high risk pregnancy, preparation for the postnatal period, engagement, and time spent alone with the child, Postnatally involvement.

Child factors included: Child gender, child temperaments.

Health care services factors include: Fathers’ presence during the birth of their infants, Nurses’ practices, Health care providers support, prenatal childbirth education, need- based education, postnatal education, and provide practical information about baby-care.

| Author (Year Published) | Study Design | Study Participants | Data Collection Methods | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sloper et al. (1993) (15) | Descriptive study | 72 fathers | Questionnaire | Father psychological distress, Personality factors, coping strategies, life events and socio-economic disadvantage, child gender effect on father adaptation. |

| Gage et al. (2002) (16) | Qualitative study | 19 fathers | Focus groups discussion | Physical, emotional, and financial preparation of fathers in antenatal is an effective factor in father adaptation. |

| de Montigny et al. (2006) (17) | correlative study | 160 fathers | Nurses’ practices contributed to fathers’ adaptation. | |

| Premberg and Lundgren, (2006) (18) | Qualitative study | 10 fathers | Individual in-depth interview | Alternating between work and home, changing relationship towards partner, developing relationship with their child changing life, becoming a father |

| Ahmann (2006) (19) | Qualitative study | 14 fathers | Interview | Health care providers can increase their own awareness of paternal concerns and needs to best encourage paternal involvement. |

| Sevil et al. (2007) (20) | Descriptive study | 3750 fathers | Questionnaire | Age, occupation and health insurance educational level of fathers were significantly with father’s adaptation. |

| Fagerskiold et al. (2007) (21) | Qualitative study | 20 fathers | Individual in-depth interviews | Experiences of antenatal, anxiety, lack of Support, preparation for the postnatal period, postnatally involvement and practical information about baby-care are effective factors in father adaptation. |

| Premberg et al. (2008) (22) | Qualitative study | 10 fathers | Interview | Engagement and time spent alone with the child, participate in postnatal childbirth education and need based education effect on father adaptation. |

| Deave and Johnson (2008) (23) | Qualitative study | 20 fathers | Semi-structured interviews | Lack of support, prenatal preparation and information given in the antenatal period, child care is important for paternal adaptation. |

| Katz-Wise et al. (2010) (24) | Cohort study | 550 fathers | Questionnaire | Changes in gender-role, attitudes and behavior following the birth of a child may be attributed both to transitioning to fatherhood. |

| Solmeyer et al. (2011) (25) | correlative study | 133 fathers | Questionnaire | Positive temperaments of children effect in father adaptation. |

| Guzzo (2011) (26) | Cohort study | 3525 fathers | interview | Health provider support is affected fathers adaptation |

| Lee et al. (2013) (27) | Qualitative study | 39 fathers | Semi-structured interviews | Information especially in key domains of effective co-parenting and communication is necessary for the transition to parenthood |

| Carlson et al. (2014) (28) | Qualitative study | 47 fathers | Focus groups discussion | Fathers’ social location affecting adaptation of fathers |

| Lu et al. (2014) (29) | cross-sectional survey | 194 fathers | Questionnaire | Satisfaction with marriage, infant’s gender, postnatal education, culture, and policies need to be considered by health care support facilitate to fathers adaptation. |

| Kowlessar et al. (2015) (30) | Qualitative study | 10 fathers | semi-structured interview | Antenatal education classes can be effective for father’s adaptation. |

| Eskandari et al. (2015) (31) | Qualitative study | 15 fathers | Individual in-depth interviews | Participation in child caring, training programs and ample information are necessary for father’s adaptation. |

| Dollberg et al. (2016) (32) | Prospective longitudinal design | 43 fathers | questionnaire | Prenatal distress, and to some degree high risk pregnancy, are risk factors that may interfere with the early formation of parent-infant relationship. |

| Eskandari et al. (2016) (33) | Qualitative study | 17 fathers | In-depth semi-structured interviews | Self-efficacy and satisfaction of father, knowledge, attitude and skills of the fathers, and support, manage the new situation, accepting the realities of life, trusting in God, and hope for the future is necessary for paternal adaptation. |

| Eskandari et al. (2016) (34) | Qualitative study | 15 fathers | Semi-structured interview | Proficiency, skilled director, Faithful, hardworking, Self-management. |

| Yanes et al. (2017) (35) | Descriptive study | 62 fathers | Questionnaire | Increased hope, social support, coping efficacy is associated with high level of father’s adaptation; and uncertainty is associated with lower adaptation. |

Characteristics and Main Findings Included in the Systematic Review

4. Discussion

This study drew on a variety of documents in the research literature and introduces strong evidence of effective factors of father adaptation. Due to systematic search of the literature in this review we feel our study result is a comprehensive representation of effective factors of the father’s adaptation. The potential advantages of this data are described as evidence-based research about factors influencing the father’s adaptation.

Documents commonly showed a wide range of effective factors in the father’s adaptation. The results of various researches have revealed the paternal demographic characteristics such as age, occupation, and educational level in father’s adaptation. Sevil et al., (2007) performed a study on 3750 first time fathers. It showed age, occupation, and health insurance educational level of fathers were significant with the father’s adaptation (20). Fathering is different for a 22 year old and a 42 year old. These men will have different attitudes, maturity levels, and experiences with their own fathers. These need to be taken into account in the planning of services and programs (3).

The results showed that psychological distress such as anxiety, stress, and emotional features influence the adaptation of the father. Also, unsuccessful coping strategies with stress have been associated with difficulties in adaptation of the father (36).

Among reviewed researches, some studies have reported that satisfaction with marriage is necessary for paternal adaptation. Recent evidence suggests that both maternal and paternal adaptation have been associated positively with the quality of the marital relationship, suggesting that efforts to enhance prenatal attachment or enhance the quality of the relationship between partners may have reciprocal effects (37).

The evidence is conclusive about the importance of antenatal education classes and father’s preparation for the postnatal period. This finding is consistent with the results of the previous studies.

Among reviewed studies, some of studies revealed the impact of child gender on the father’s adaptation. These results were confirmed by those of the previous studies conducted on child sex. Sloper et al. (1993) reported the role of child gender on paternal adaptation (15).

Our results in this systematic review showed that engagement and time spent alone with the child had a postnatally involvement affecting on paternal adaptation. Finding from the study by Premberg et al. (2008) shows there is a correlation between father involvement and father’s adaptation (22).

About other of effective factors, this review showed that health care providers support is effective on paternal adaptation. The results of the previous researches revealed that one of the most important factors affecting the adaptation of the parent are health care provider’s practices (38).

The main strengths of this study were 2 investigators who independently extracted data and reviewed the articles to obtain data accurately.

Our study had some limitations. Some eligible studies might have been missed due to the fact that the searches were merely conducted on the most common sources and therefore did not include unpublished documents or consultation with experts. On the other hand, we did not contact authors to obtain raw data if it had not been presented in the study. Some of the included studies in this study were surveys using closed-ended questions or limited with respect to generalizability and sampling.

4.1. Conclusions

This review article presents a comprehensive summary of effective factors in father adaptation. Father’s adaptation factor assessment provides an avenue for decision making and health care providers to access need-based education for father’s adaptation. The findings of this study showed a wide range of effective factors such as age, occupation, educational level, satisfaction with marriage, antenatal education classes, care providers support, and child gender in father’s adaptation. Furthermore, one of the major findings of this study was impact of psychological distress on an adaptation of the father.

We suggest several recommendations for future investigation to better progress the fatherhood educational program: need-based intervention is an effective strategy for improving the father adaptation. Therefore, carefully controlled and adequately strengths of intervention studies are necessary for a survey and comprehend effects of need-based intervention. Evidence-based intervention studies are also needed to evaluate the impact of different promotional strategies on the father’s adaptation.