1. Background

The blood levels of a number of hormones changes during a 24-hour period (1-4). This circadian rhythm in hormone secretion is not only affected by sleep-wake cycle (such as growth hormone), but also an endogenous biological timing system (such as cortisol). In order to regulate the normal concentrations of hormones in the blood, appropriate interaction of sleep and biological systems is necessary. Under normal situations, the sleep-wake cycle and endogenous timing system are harmonized and properly regulate hormone levels. However, circadian misalignment may have adverse health consequences on metabolic and hormonal factors (5).

Ghrelin, a 28-amino-acid peptide, was purified in 1999 from rat stomach. Ghrelin is produced by the oxyntic gland in the stomach (6). Peripheral or central injection of ghrelin increases intake of food and body weight in rodents (7, 8). Plasma ghrelin level in humans increases prior to the usual meal times and fall thereafter (9, 10). Therefore, it seems that ghrelin secretion is regulated by caloric intake. Ghrelin also plays a role in neuroendocrine and behavioral responses to stress (11).

Previous reports have shown that the release of hormones such as ghrelin and leptin, which play a central role in regulating glucose and appetite, is dependent on sleep duration and quality. Therefore, sleep deprivation may have adverse effects on endocrine function and metabolism (12). A few studies have been conducted on the 24-hour pattern of ghrelin secretion in subjects who have a normal sleep duration (13, 14), but to the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted on the effects of sleep deprivation on this pattern. Soldiers who spend their military years at the AJA University of Medical Sciences are deprived of the normal sleep-wake cycle as part of their military service period. Therefore, our study was carried out to establish:

(1) Does the serum ghrelin level follow a circadian rhythm in soldiers with normal sleep pattern?

(2) Does the shift work affect the 24-hour pattern of ghrelin secretion?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The study was conducted on healthy young soldiers who served in AJA University of Medical Sciences; all the participants were aged 19 - 23 years old. After providing the necessary explanations in relation to the study, the soldiers were invited to participate in the study. Sixteen soldiers volunteered to participate in the study. The participants were assigned to two groups. The first group had regular sleep-wake cycle (n = 8), the soldiers were sleeping from 22 P.M. until 6 A.M. and were awake for the rest of the day and were doing their daily tasks. The second group consisted of individuals who did not have normal arousal cycle (n = 8). Their plan within 24 hours was two hours awake for guard duty, standby alert for two hours, and sleep for two hours. The program was repeated during 24 hours.

The participants were given three meals a day (i.e., breakfast, lunch, and dinner) at specified times.

2.2. Blood Sampling and Hormone Assay

Blood samples were taken at 4-hour intervals during both wakefulness and sleep within 24 hours (from 10 A.M. on day 1 until 6 A.M. on day 2). Therefore, six blood samples were taken from each subject within 24 hours.

The blood samples were collected in tubes containing Na-EDTA (1 mg/mL blood) and aprotinin (300 kallikrein inhibitor units/mL blood), which were stored on ice. Immediately after withdrawal, the blood samples were centrifuged at 2,600 g for 7 min at 4°C, and serum was aliquoted and frozen to -20°C until different assays were performed.

Serum cortisol (DRG Instruments GmbH, Germany) and ghrelin (Crystal Day Christian Day kit, China) concentrations were measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method.

2.3. The Calculations

The average hormone concentrations were calculated as the area under the curve divided by 24 h (15).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All the values were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). The normal distribution of the data was evaluated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To determine the existence of daily changes in the secretion of the hormones, we used repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The independent t-test was used to compare the average concentration of hormones over 24 hours between the two groups. SPSS version 18 was used for all the statistical analyses. P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

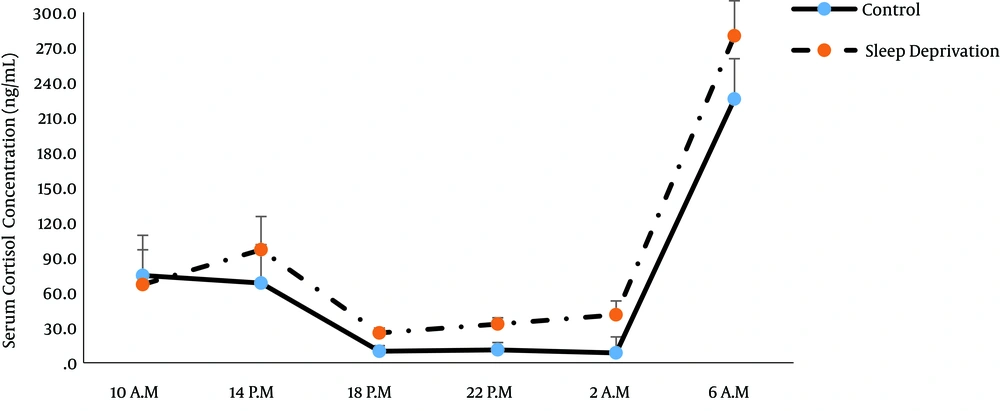

Analysis of the data using repeated measures ANOVA showed the main effect of time on cortisol concentration (P = 0.006; Tables 1 and 2). Therefore, there was a circadian rhythm for cortisol in both groups with a peak at 06.00 A.M. (Figure 1). However, cortisol secretion pattern was not significantly different between the groups (P = 0.1; Table 2). Thus, sleep deprivation had no significant impact on this pattern.

| Within Subjects Effect | Mauchly’s W | Approx. Chi-Square | Df | P Value | Epsilon | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenhouse-Geisser | Huynh-Feldt | Lower-Bound | |||||

| Group | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0 | - | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Time | 0.000 | - | 14 | - | 0.317 | 0.613 | 0.200 |

| Group × time | 0.000 | - | 14 | - | 0.227 | 0.272 | 0.200 |

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenhouse-Geisser | Group | 1.000 | 18991.807 | 5.171 | 0.108 | |

| Error (group) | 11018.188 | 3.000 | 3672.729 | |||

| Time | 320667.506 | 1.585 | 202328.88 | 18.944 | 0.005 | |

| Error (time) | 50782.717 | 4.755 | 10680.648 | |||

| Group × time | 8926.088 | 1.135 | 7867.448 | 817 | 0.442 | |

| Error (group × time) | 32784.416 | 3.404 | 9632.055 |

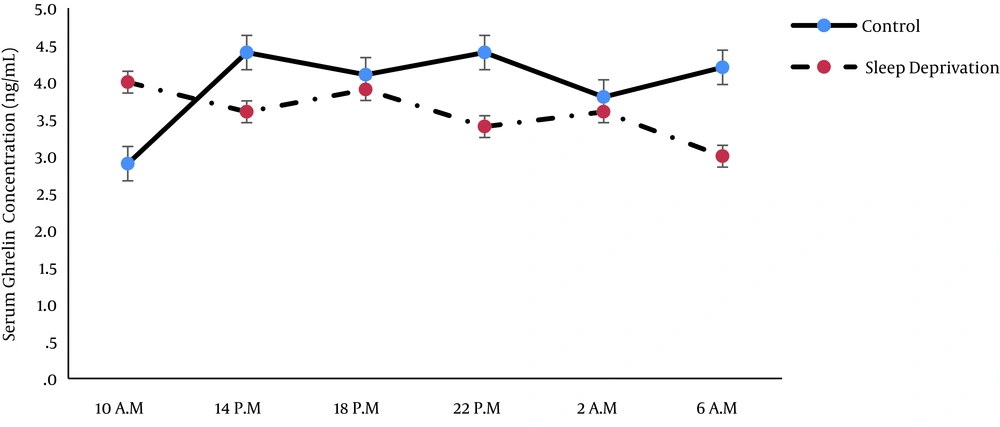

Ghrelin concentration was not significantly different between the groups (P = 0.46) and at various times (P = 0.57; Tables 3 and 4). In other words, both normal and sleep disrupted groups did not show an obvious diurnal pattern for ghrelin, and sleep disruption did not significantly affect the temporal pattern of serum ghrelin concentration, although a non-significant variation was detected (Figure 2).

| Within Subjects Effect | Mauchly’s W | Approx. Chi-Square | df | P Value | Epsilon | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenhouse-Geisser | Huynh-Feldt | Lower-bound | |||||

| Group | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0 | - | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Time | 0.003 | 30.326 | 14 | 0.012 | 0.368 | 0.493 | 0.200 |

| Group × time | 0.011 | 23.029 | 14 | 0.084 | 0.441 | 0.653 | 0.200 |

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphericity Assumed | Group | 3.546 | 1 | 3.54 | 0.592 | 0.467 |

| Error (group) | 41.897 | 7 | 5.98 | |||

| Greenhouse-Geisser | Time | 4.499 | 1.84 | 2.444 | 0.551 | 0.575 |

| Error (time) | 57.139 | 12.88 | 4.43 | |||

| Sphericity Assumed | Group × time | 13.323 | 5 | 2.66 | 5.29 | 0.001 |

| Error (group × time) | 17.616 | 35 | 0.503 |

The average concentrations of ghrelin and cortisol throughout the 24-hour period have been shown in Table 5. Sleep disruption did not show a significant impact on the mean concentrations of cortisol and ghrelin during 24 hours.

| Control Group | Disrupted Sleep Group | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisolb | 41.25 ± 7.7 | 61.61 ± 8 | 0.1 |

| Ghrelinb | 3.37 ± 0.3 | 3 ± 0.3 | 0.4 |

an = 8

bValues are presented as ng/mL

4. Discussion

Earlier studies have shown that alteration in activity time, sleep pattern, and feeding behavior influence the circadian control of the endocrine system (16, 17). In our study, the secretion pattern of cortisol was similar to the 24-hour rhythm of cortisol observed in previous reports (3, 12) with peak levels occurring early in the morning (06.00 A.M.), and sleep deprivation had no significant effects on this pattern. The results of Scheer et al. showed that cortisol secretion pattern was mostly influenced by the internal daily rhythms rather than behavior (fasting-feeding and sleep-wake) cycles (18).

The study by Miyauchi et al. indicated that night shift (from 0:00 to 8:00) did not impact the circadian rhythm of cortisol in male nurses. In addition, the concentration of cortisol in a night shift group did not differ from that of a control group (19). Also, in our study, the average concentration of cortisol throughout the 24-hour period was not significantly higher in the deprived sleep group than the control group.

In agreement with the present study, an earlier study did not show a significant circadian rhythm for acylated ghrelin in normal subjects that received three meals a day (14). It seems that the nutritional state of subjects influences on ghrelin secretion pulses. Fasting increased all parameters of ghrelin pulsatile secretion (20). In contrast to our study, some previous studies have reported a circadian rhythm for ghrelin (13). This can be due to methodological differences that prevented comparison of this study with other works.

(1) The number of blood samples: In our study, six blood sampling were obtained during 24 hours, whereas in other works, 24 - 72 samples were drawn during 24 hours (13, 14, 21).

(2) Age and sex: Most preceding studies that reported circadian rhythm for ghrelin were performed in female subjects with a very wide age range (13, 21).

(3) Sleep and sleep deprivation condition: In most previous studies, effects of sleep on diurnal or nocturnal pattern of ghrelin secretion were investigated in-vitro.

In conclusion, it seems that ghrelin does not show a circadian rhythm and sleep deprivation does not significantly impact the 24-hour secretion pattern of cortisol and ghrelin.

4.1. Limitations of the Study

In this study, blood sampling was performed every four hours. Therefore, we had to awaken the control group soldiers during their normal sleep period (from 10:00 P.M. to 6:00 A.M.). In order to minimize the effects of sleep disturbance in this group, the blood collection program was designed to collect blood at night before bedtime (10:00 P.M.) and in the morning immediately after getting up (6 A.M.). Thus, the control group soldiers woke up only once during their normal sleep cycle (midnight at 2 o’clock), which was one of the major limitations of this study. Other study limitations were limited sample size and the low number of samples taken over 24 hours.