1. Context

The concept of self-efficacy is the belief in one’s capabilities in the aptitude to overcome challenges, adversities, and obstacles in one’s life (1). It is a predictor of health behavior and as the most important part of individual behavioral change (2). Also, it is effective as a protective factor against risky sexual behaviors such as inconsistent condom use (3).

Psychologist Albert Bandura has indicated self-efficacy can boost confidence in people’s ability to achieve positive behaviors, as well as the opinion that they have control of sure situations in their surroundings (4). Self-efficacy is the most important part of Bandura’s social cognitive theory (SCT) to be used in health promotion (5).

The most key concepts of sexual health related to Bandura’s SCT that should be understood is sexual self-efficacy (SSE) (6). SSE is one’s belief to be able as someone who can make decisions about their sexuality and avoid high-risk sexual behavior (7).

SSE focuses’ on a person’s control over sexual life, competence and ability of the person as a sexual agent, ability to involve in safe sexual action, suitability as a sexual partner and ability to obtain sexual satisfaction (8).

SSE plays a fundamental role in sexual decision-making, a result being the prevention of risky sexual behavior sexually transmitted infections (9). SSE has the highest communication with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) prevention. It is also known as perceived control and is a commonly used predictor of sexual behavior because young people who have higher perceived SSE reveal less risky sexual activity (10). The high perceived SSE of the persons can increase pleasurable and enjoyable sex, healthy sexual activities, followed by sexual health and health promotion (6). Enhancement of SSE is an important component for effective behavioral change, aimed at reducing unsafe sex (5).

There has been a developing comprehension that SSE is affected by macro factors that are substantial for realization of decision-making about sexual issues and behavior (11). SSE (i.e. being sensibly confident and having a feeling of mastery about how to manage oneself sexually) directing girls to make better decision- making about sexual behavior and to more positively explicate their experiences (9).

Although evidence suggests that SSE is necessary for the sexual function and safe sexual behavior (11), the factors related to the SSE remain marginalized and neglected in sexual health education programs. While understanding these factors may improve people’s knowledge, attitudes, beliefs or behavioral practices and could lead to a reduction in risky sexual behavior (12).

Therefore, it seems that a review of the literature that is not restricted to youth or to peer-reviewed publications, or to specific types of outcomes or study designs, that examines the literature regarding the only sexual self-efficacy is necessary. The objective of this scoping review is to describe the scientific literature on the related factors. The results of this study can be used to plan educational and promotional interventions for promoting sexual health.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

We conducted a comprehensive review of literature published between 1990 and 2018 focusing on the factors related to the SSE. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews (PRISMA) principles were used to extend the process explained in this review (13). A search of the literature was performed using PubMed, Web of Science, Social Science Research Network (SSRN), CINAHL, Psych INFO as databases for English documents and Iran Medex, SID, Magiran, Google Scholar and Iran Doc as databases for Persian documents. ProQuest Dissertations, gray literature publications of the New York Academy of Medicine, WHO Global Health Library, Scopus, Popline and PAIS were searched for gray literature. Articles were identified using the search terms “self-efficacy”, “sexual”, “sexual self-efficacy”, “sexual health”, “health” “psychology” and “public health” according to the medical subject headings (MeSH).

Manual reference checks of publications were performed to supplement the electronic search.

The finds of peer-reviewed search were entered into EndNote by SSE subject. In return, because of restrictions on the investigative capacity of the databases for gray literature, results of the gray search were entered into EndNote in relation to SSE more widely.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Two authors autonomously assessed every record caption for inclusion in this review, and a third author adjudicated when disagreement occurred. Detailed records were made about the purpose of each document, participants, data collection, methods of research, validity and reliability of the questionnaire, and the results of the study. We included studies meeting the following criteria: studies that explored factors related to SSE, published in English and Persian language. Published between 1990 to 2018. Published qualitative, mixed methods, or quantitative studies. Studies were excluded when the study topic was irrelevant to the SSE.

2.3. Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

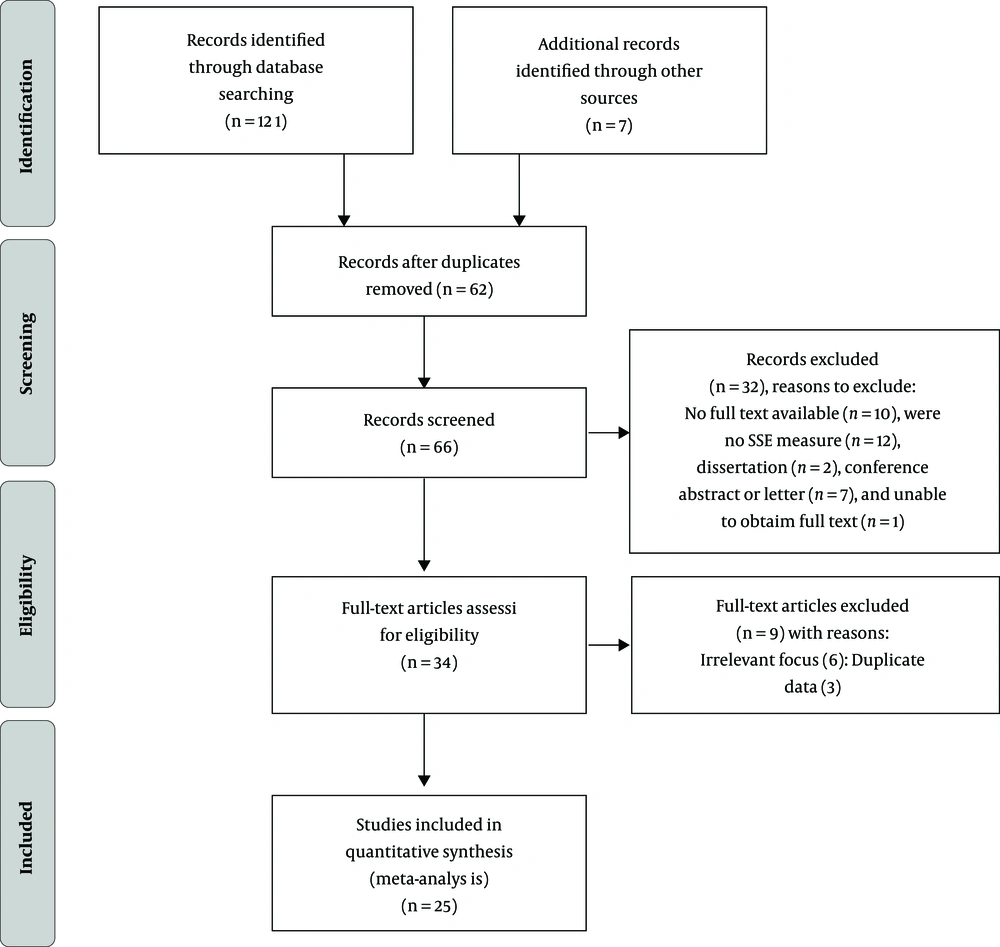

The checklist of critical appraisal skills program (CASP) was used for evaluating methodologies, ensuring reliability, and for drawing the right conclusions on qualitative and quantitative studies. Principles of appropriate research method, collection of data, data analysis, the validity and clarity of results which used to evaluate the weaknesses and strengths of each document as inclusion or exclusion criteria in this review (14). By determining the record, according to these factors, we were able to recognize strengths and weaknesses of studies. Whole duplicate documents were recognized and deleted. Two reviewers autonomously screened the title and abstracts of the article for eligibility. Then, the reason for removing studies was recorded. According to the inclusion criteria, 25 relevant articles were retrieved.

3. Results

A total of 128 records were excluded from screening the title and abstract. Of the remaining 66 records, full texts were sought and 25 were retained. Reasons for record excluded, No full text available (n = 10), were no SSE measure (n = 12), dissertation (n = 2), conference abstract or letter (n = 7), and unable to obtain full text (n = 1) (Figure 1).

We’ve found some of main factors related to SSE. These factors can be divided into 4 broad groups that include:

• Socio-demographic factors: age, race, socioeconomic status, parental support, social support, religious obligations, negotiation skills, addicts, working hours, history of delivery, physical problem.

• Marital status factors: failure in marital, marital satisfaction, marital quality, marriage duration, intimacy.

• Sexual history factors: sexual self-concept, sexual experience, confidence in sexual relationships, sexual activity, sexual self-schema, sexual adjustment, childhood sexual abuse, sexual disorders, sexual risk cognition, experiences of abuse or violence, partner’s belief, experiences of sex-therapy training.

• Psychological factors: obsession, psychosis, anxiety, depression, paranoia, phobia, individual sensitivity, aggression.

Full details of the 25 included records are exposed in Table 1.

| Authors, Year | Design | Sample Size | Data Collection Technique | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oluwole (1990) (15) | Descriptive | 2000 women | Questionnaire | The findings showed a significant relationship between SSE and marital satisfaction. |

| Seal et al. (1997) (16) | Correlative | 121 women | Questionnaire | Findings explore the connection between SSE on the amount of sexual activity, which in turn, is positively related to risk taking. |

| Reissing et al. (2005) (17) | Cross-sectional | 84 women | Questionnaire | The findings suggest that SSE mediated the association between sexual adjustment and sexual self-schema. |

| Steinke et al. (2008) (18) | Correlative | 59 healthy elders and 85 patients with HF | Questionnaire | Research findings suggest there is a relationship between SSE and sexual activity. A higher sexual self-concept of greater SSE were predictors of sexual activity. |

| Rostosky et al. (2008) (19) | Cross-sectional | 388 students | Questionnaire | Males reported lower sexual esteem and lower SSE than females. Sexual self-esteem uniquely predicted higher SSE scores. |

| Vaziri et al. (2010) (20) | Correlative | 194 women | Questionnaire | Research results suggest a relationship between SSE and marital satisfaction and SSE scores is predicted of marital satisfaction. |

| Sarikhani et al. (2011) (21) | Quasi-experimental | 200 women | Pre and post-test in experimental and control group | The findings showed that women’s SSE reduces after delivery. |

| Viseskul et al. (2013) (22) | Cross-sectional | 92 HIV-positive | Questionnaire | The scores of the SSE were significantly lower in those aged 17 to 21 than in 14 to 16. |

| Zimmer-Gembeck (2013) (23) | Correlative | 199 women | Questionnaire | Research findings explore the indirect association of women’s autonomy with SSE. |

| Nooripour et al. (2013) (24) | Quasi-experimental | 40 couples | Pre and post-test in experimental and control group | Findings indicate that training significantly improved marital satisfaction and SSE. |

| Redmond and Lewis (2014) (25) | Cross-sectional | 214 women | Questionnaire | The results indicated significant differences exist between genders in perception of SSE. Having high negotiation skills were significant predictors for highly perceived SSE. |

| Nooripour et al. (2014) (26) | Case – Control | 40 couples | Pre and post-test in experimental and control group | Findings indicate that training significantly improved SSE of participants. |

| Widman et al. (2013) (27) | Cross-sectional | 476 people living with HIV | Questionnaire | The results indicated that greater SSE predicted unsafe intercourse. |

| Alirezaee et al. (2014) (28) | Historical cohort | 170 fertile and 85 infertile women | Questionnaire | The results indicated that infertility is associated with poor SSE. |

| Salehi et al. (2015) (29) | Cross-sectional | 200 participants with physical-motor disabilities | Questionnaire | Research findings indicated that sexual self-efficacy score in women with physical-motor disabilities were higher than men in all domains and there was a relationship between men’s sexual self-efficacy with their self-esteem. |

| Hsu et al. (2015) (30) | Cross-sectional | 713 Nursing students | Anonymous mailed questionnaire | Findings suggest that sexual self-concept significantly predicted SSE. SSE predicted by sexual risk cognition. |

| Norton et al. (2016) (31) | Longitudinal | 296 couples | Computer-assisted self interviews | The results showed higher artist status principals were considerably related to more SSE, higher artist toughness principals were related to less SSE, and higher artist anti-femininity principals were considerably related to less SSE. |

| Rosenthal et al. (1991) (10) | Cross-sectional | 1788 | Questionnaire | The finding indicated that Females were significantly more SSE than males |

| Zare et al. (2016) (7) | Correlative | 79 women | Questionnaire | The result shows that SSE in women has a positive effect on marital satisfaction. |

| Tung et al. (2011) (32) | Cross-sectional | 996 college students | Questionnaire | The findings showed that SSE prevents of female students to practice unsafe sex. |

| Hajinia and Khalatbari (2017) (9) | Quasi-experimental | 30 women | Pre-test and post-test in experimental and control group | The results from this study revealed that sex therapy improves SSE. |

| Addoh et al. (2017) (33) | Multivariable logistic regression models | 157 female college students | Questionnaire | Results showed that a greater degree of SSE is associated with increased of safe-sex practice. |

| Malonzo and Chavez (2012) (34) | Descriptive study | 80 women | Questionnaire | There was a significant relationship between SSE and sexual risk cognitions. |

| Golmakani et al. (2018) (35) | Experimental | 79 women | Pre and post-test in experimental and control group | The results revealed that the pelvic muscles exercise in women after delivery improve the SSE. |

| Fedding and Rossi (1999) (36) | Cross-sectional | 305 male and female college students | Questionnaire | The results suggest that SSE can help in enhancing safer sex adoption and adherence at both public and individual sexual health levels. |

Characteristics and Main Result of Studies Included in the Systematic Review

4. Discussion

SSE has become an important structure in sexual health in recent years. From the early 20th century, researchers in the sexual health sector have tried to identify the positioning and factors that affect SSE (37). At least two thirds of the studies reported SSE as a key protective factor (38). The results presented here provide related factors to SSE. Socio-demographic, marital status, sexual history, psychological disorders appeared to be related to SSE.

Twenty-five studies were used to identify the factors.

A biological factor affecting SSE is age. The result is that with increasing age, SSE is promoted. During in the early adolescent level SSE is lower than young people (22). Before school age, sexual knowledge grows as the gender identity is shaped. SSE slowly grows over time. Over time also, sexual anxiety is reduced and SSE is evolving, which affects the individual’s future behavior (39).

It has been shown that gender is significantly associated with SSE. Gender differences in SSE, such that the female has stronger SSE than male, may be influenced by societal engrained sexual scripts that depict the sexual desires of young men as something that should not or possibly cannot be suppressed (25).

The findings showed a significant relationship between SSE and the marital status (40). Higher SSE is accompanied by marital satisfaction and experiences and more sexual activities in one’s lifetime (7). Also, divorced individuals have more SSE, greater incentive to avoid high-risk sexual behaviors and report more fear (40).

SSE is higher in non-Africans than other ethnic groups (8). African and African - American women have a unique history of slavery, exploitation and victimization in their own countries and their sexuality is debated. In addition, contradictory and negative implications such as hypersexual and asexual “Mammy type” can be dangerous. When sexual stereotypes are associated with the image of vixen, bad girl, anxiety, incompetence and sexual dysfunction appear (36).

A number of studies have shown that people with higher levels of education have higher SSE (22). Also, the literature review shows that increased social support or family communication predicted improved SSE, especially for young women (4). High negotiation skills and a sexual partner’s belief were predictors of high perceived SSE (25).

SSE has a relationship with marriage duration (41), sexual disorders (42), marital quality (26), sexual activity (43), failure in marital, intimacy (36). Seutlwadi’s investigation in 2015, showed that women who ever experienced forced sex had lower SSE (37). Slonim-Nevo and Mukuka’s study indicates that the sexual abuse in adolescence was related to low SSE (38).

Also, confidence in sexual relationships anticipates higher levels of SSE (39). Hsu et al. (30) revealed the effect of sexual self concept on SSE. The results from their study supported that sexual self concept has a positive and direct effect on SSE and participants with higher sexual self concept and higher sexual risk cognition have higher SSE. Their sexual risk cognition showed to have a positive influence on SSE. Adolescents had higher sexual self-esteem uniquely predicted higher SSE scores (19, 41).

Many studies suggest that SSE increases through participation in educational programs (26, 44, 45). For example, Nooripour et al., in their study showed that sex-therapy training positively affects SSE (26).

The majority of research examining the link between mindfulness training on increasing the SSE confirm this link. Also, women who reported a high level of violence were more probable to have low SSE (45).

There was a significant and negative relationship between the depression, obsession, anxiety, individual sensitivity, phobia, aggression, psychosis and paranoia with SSE. In total, Vaziri et al. showed that physical complaints, depression, and psychosis were able to predict SSE (20).

4.1. Conclusions

This review presents facts in the field of factors related to SSE. The results of this review indicate that factors related to SSE included: socio-demographic, marital status, sexual history and psychological factors. With regards to the important role of SSE in sexual health, deeper perceptive factors related to SSE are needed. More comprehension of these agents can acquaint targeted approaches in order to improve SSE and reduce the sexual problems.

On the other hand, health providers and sex therapists can benefit from the results of this study to obtain a further understanding of the foundations of sex and, eventually, to help increase SSE because some of the sexual problems could be obviated by increasing SSE.

Since the findings of this review have been based on longitudinal and cross-sectional studies with various designs and sample size, for a better recognition of the factors related to the SSE, A prospective cohort study is suggested.