1. Background

Morbid obesity is known as a global public health concern in the last few decades. This medical condition increases the risk of several common pathological disorders like hypertension, atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes, and cancer (1). Body mass index (BMI) is the main indicator of obesity, calculated as body weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). BMI is classified in normal individuals (18.5 - 25 kg/m2), overweight people (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), and obese patients (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). According to available estimates for 2030, about 2 billion and 1.12 billion people around the world will suffer from being overweight and obese, respectively (2, 3). The multifactorial etiology of obesity includes environmental, behavioral, and genetic factors (4). The change in lifestyle and the imbalance between energy absorption and consumption lead to obesity, in which excessive intake of energy and reduced physical activity are associated with weight gain and obesity (5). It has been shown that genetic factors also play an important role in the obesity development as well as environmental factors. By studying families and twins, hereditary predisposition to obesity was estimated to be around 40% - 70% (6, 7). Based on several genetic association studies, fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene is known as the most important contributor to polygenic obesity (8). This gene is located on chromosome 16 and encodes FTO protein, which is a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent DNA demethylase (9). FTO protein is widely expressed in fetal and adult tissues with highly conserved amino acid sequence in vertebrates from the fish to human. The highest levels of this protein are found in the hypothalamus and a region of the brain, which is critical for control of energy homeostasis and eating behavior (1, 9, 10). Different studies indicated that the regulation of FTO mRNA expression is related to food intake (9, 11, 12), blood glucose level (13), body weight (14), and energy consumption (15, 16). Fischer and colleagues indicated a significant increase in energy expenditure in FTO-deficient mice, which leads to leanness regardless of a normal or high fat diet (15). Church et al., also showed a high enhancement in body fat and mass in mice with FTO overexpression (17). Taken together, these experiments confirm the significant involvement of FTO in energy homeostasis. Several studies demonstrated the association between FTO single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and obesity in 2007 (1, 18, 19). Thereafter, various epidemiological studies have been carried out to confirm the existence of association between FTO SNPs and obesity (20, 21). The two most studied polymorphisms of FTO associated with obesity include (rs1421085) and (rs17817449) (21-24). Given that these two polymorphisms are located in the conserved regions of the first intron of the FTO gene, they may have an effective role in the gene function (24).

2. Objectives

Despite various studies in different populations, to our knowledge, there is still no study on the association of the FTO genetic variations (rs1421085 and rs17817449) and obesity incidence in Iran. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine and compare two FTO SNPs (rs1421085 and rs17817449) in obese patients and healthy controls. The potential association between genetic variations and obesity incidence as well as some demographic and clinical characteristics of obese patients were investigated in a population in southern Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population and Blood Samples

Blood samples were collected from 90 obese patients who were candidates for sleeve gastrectomy between the years of 2017 and 2018 at a university hospital in Shiraz (Shahid Faghihi Hospital). A total of 90 sex and age-matched healthy controls with normal BMIs were included in this study. All subjects had read and signed informed consents and ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

3.2. DNA Extraction and FTO Genotyping

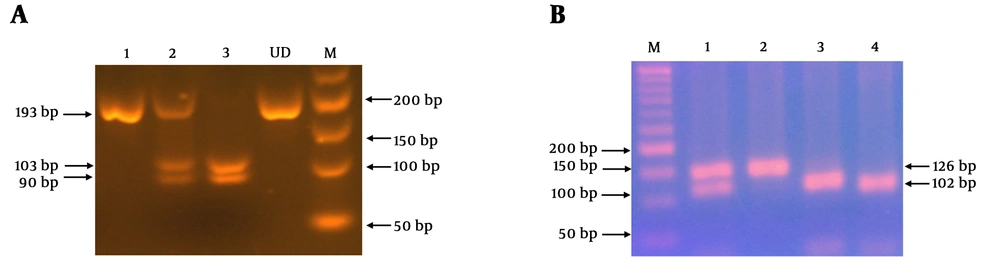

After Blood collection in EDTA-anticoagulant tubes, total genomic DNA was extracted from 500 μL of whole blood using a standard Proteinase K, salting-out method (25, 26). DNA was quantified by Nano Drop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and stored at -20°C. Genotyping of FTO at two intronic regions (rs1421085 and rs17817449) was performed by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) method. Briefly, genomic DNA from the samples were amplified by PCR and then incubated with restriction endonucleases at 37°C for an hour. Digested products were electrophoresed on 3% agarose gel, stained with GelRed (Biotium, Belgium) and visualized under UV illumination. PCR-RFLP reliability was confirmed using DNA sequencing. Details regarding the primer sequences (SinaClon Co., Iran), PCR product sizes, Mae III (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and Cail (AlwNI) (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) restriction enzymes, and also digestion products are summarized in Table 1.

| Primer Sequences | PCR Product | Enzyme Recognition Site | Digestion Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs1421085, T/C | |||

| Forward: 5'-TAGTAGCAGTTCAGGTCCTAAGGCGTG-3'a | 126 bp | MaeIII | Wild type allele T: one fragment (126 bp) |

| Reverse: 5'-TGGAGGTCAGCACAGAGGC-3' | 5'↓GTNAC3'; 3' CANTG↑5' | Mutant allele C: two fragments (102 and 24 bp) | |

| rs17817449, G/T | |||

| Forward: 5'- GAGGAGATTGTGTAACTGGAG-3' | 193 bp | CaiI | Wild type allele G: one fragment (193bp) |

| Reverse: 5'- CAAGGAAGCCCGTAGAAG -3' | 5'CAGNNN↓CTG3'; 3'GTC↑NNN GAC5' | Mutant allele T: two fragments (103 and 90 bp) |

Primers and Enzymes Used for PCR-RFLP and Their Products Size

3.3. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software package (version 20) (Chicago, IL). Qualitative and quantitative variables were analyzed using chi-square and One-way ANOVA tests, respectively. The statistical significance was defined as two-tailed P values less than 0.05.

4. Results

Two single nucleotide polymorphisms located in the intronic regions of FTO gene (rs1421085, rs17817449) were investigated in 90 patients with morbid obesity and 90 healthy controls. Case-control matching was performed in respect to age and sex. Subjects were more likely to be female (71.1% of cases and 67.8% of controls, P = 0.6). The mean ± standard deviation of the age were 38.39 ± 9.66 for cases and 40.71 ± 9.32 for controls (P = 0.1). As shown in Figure 1, genotype analysis was performed by PCR-RFLP using MaeIII and CaiI enzymes for FTO rs1421085 and FTO rs17817449, respectively. Genotype and allele frequencies in cases and controls are summarized in Table 2. The case group was in the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Owing to rare allele frequency in the control group, the Hardy-Weinberg exact test was applied (27). The control group was compatible with this equilibrium (P > 0.05). We investigated the potential association between FTO SNPs and the risk of morbid obesity. In case-control comparisons, genotype distribution was significantly different for both polymorphisms (P < 0.0001). Controls with wild type TT and GG genotypes were used as the reference categories for rs1421085 and rs17817449, respectively, and odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were determined after adjustment for age. In this regard, OR (95% CI) were 0.41 (0.13 - 1.1) for CT (rs1421085), 13.83 (6.04 - 31.67) for CC (rs1421085), 0.07 (0.01 - 0.32) for GT (rs17817449), and 0.63 (0.99 - 1.1) for TT (rs17817449). As shown in Table 2, the frequency of heterozygote genotypes of both polymorphisms was higher in the control group (TC for rs1421085 and GT for rs17817449). However, the frequency of homozygote mutant genotypes of both polymorphisms was significantly higher in the case group compared with the control group. This indicates that there are significant associations between these SNPs and morbid obesity. The potential association between FTO SNPs and some demographic and clinical characteristics were evaluated. Genotype frequencies and the association between these SNPs and demographic and clinical characteristics of obese patients are described in Table 3. No significant differences were found in the frequencies of two FTO genotypes (rs1421085, rs17817449) in obese patients stratified based on all evaluated factors including, type 2 diabetes, hypothyroidism, physical activity, amount of stress, consumption of fatty and frying foods, sweetmeats and fruit and vegetables, cigarette and hookah smoking, alcohol consumption, family history of obesity, FBS, TG, total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL (P > 0.05).

| Groups | rs1421085 | rs17817449 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Allele | Genotype | Allele | |||||||||

| TT | TC | CC | P Value | T | C | GG | GT | TT | P Value | G | T | |

| Patients (n = 90) | 10 (11.1) | 54 (60) | 26 (28.9) | < 0.0001 | 93 (46.5) | 107 (53.5) | 19 (21.1) | 51 (56.7) | 20 (22.2) | < 0.0001 | 108 (54) | 92 (46) |

| Controls (n = 90) | 6 (6.7) | 83 (92.2) | 1 (1.1) | 105 (52.5) | 95 (47.5) | 2 (2.2) | 84 (93.3) | 4 (4.4) | 98 (49) | 102 (51) | ||

FTO Genotypes and Allele Frequencies in Obese Patients and Healthy Controlsa

| Parameters | rs1421085 | rs17817449 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT | TC | CC | P Value | GG | GT | TT | P Value | |

| Type 2 diabetes | 0.56 | 0.36 | ||||||

| With type 2 diabetes | 1 (7.1) | 7 (50) | 6 (42.9) | 5 (35.7) | 6 (42.9) | 3 (21.4) | ||

| Without type 2 diabetes | 9 (11.8) | 47 (61.8) | 20 (26.3) | 14 (18.4) | 45 (59.2) | 17 (22.4) | ||

| Hypothyroidism | 0.53 | 0.43 | ||||||

| With hypothyroidism | 2 (13.3) | 7 (46.7) | 6 (40) | 5 (33.3) | 8 (53.3) | 2 (13.3) | ||

| Without hypothyroidism | 8 (10.7) | 47 (62.7) | 20 (26.7) | 14 (18.7) | 43 (57.3) | 18 (24) | ||

| Physical activity | 0.29 | 0.12 | ||||||

| High | 0 (0) | 6 (75) | 2 (25) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 0 (0) | ||

| Moderate | 9 (17) | 30 (56.6) | 14 (26.4) | 12 (22.6) | 25 (47.2) | 16 (30.2) | ||

| Low | 1 (3.4) | 18 (62.1) | 10 (34.5) | 6 (20.7) | 19 (65.5) | 4 (13.8) | ||

| Amount of stress | 0.9 | 0.44 | ||||||

| High | 4 (13.3) | 19 (63.3) | 7 (23.3) | 4 (13.3) | 20 (66.7) | 6 (20) | ||

| Moderate | 4 (11.1) | 20 (55.6) | 12 (33.3) | 11 (30.6) | 17 (47.2) | 8 (22.2) | ||

| Low | 2 (8.3) | 15 (62.5) | 7 (29.2) | 4 (16.7) | 14 (58.3) | 6 (25) | ||

| Fatty/frying foods consumption (freq./wk) | 0.69 | 0.12 | ||||||

| High (1) | 2 (8.7) | 16 (69.6) | 5 (21.7) | 3 (13) | 18 (78.3) | 2 (8.7) | ||

| Moderate (2 - 3) | 7 (14.3) | 27 (55.1) | 15 (30.6) | 10 (20.4) | 25 (51) | 14 (28.6) | ||

| Low (> 4) | 1 (5.6) | 11 (61.1) | 6 (33.3) | 6 (33.3) | 8 (44.4) | 4 (22.2) | ||

| Sweetmeat consumption (freq./wk) | 0.15 | 0.16 | ||||||

| High (> 4) | 4 (15.4) | 15 (55.7) | 7 (26.9) | 5 (19.2) | 16 (61.5) | 5 (19.2) | ||

| Moderate (2 - 3) | 6 (19.4) | 17 (54.8) | 8 (25.8) | 4 (12.9) | 16 (51.6) | 11 (35.5) | ||

| Low (1) | 0 (0) | 22 (66.7) | 11 (33.3) | 10 (30.3) | 19 (57.6) | 4 (12.1) | ||

| Fruit/vegetables consumption (freq./wk) | 0.13 | 0.11 | ||||||

| High (> 4) | 2 (9.1) | 17 (77.3) | 3 (13.6) | 2 (9.1) | 17 (77.3) | 3 (13.6) | ||

| Moderate (2 - 3) | 8 (15.7) | 26 (51) | 17 (33.3) | 12 (23.5) | 24 (47.1) | 15 (29.4) | ||

| Low (1) | 0 (0) | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | 5 (29.4) | 10 (58.8) | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Alcohol | 0.11 | 0.5 | ||||||

| Alcohol consumer | 4 (26.7) | 7 (46.7) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (13.3) | 8 (53.3) | 5 (33.3) | ||

| Non-consumer | 6 (8) | 47 (62.7) | 22 (29.3) | 17 (22.7) | 43 (57.3) | 15 (20) | ||

| Smoking | 0.83 | 0.62 | ||||||

| Cigarette smoker | 2 (15.4) | 8 (61.5) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (15.4) | 9 (69.2) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| non-smoker cigarette | 8 (10.4) | 46 (59.7) | 23 (29.9) | 17 (22.1) | 42 (54.5) | 18 (23.4) | ||

| Hookah | 0.16 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Hookah smoker | 4 (25) | 8 (50) | 4 (25) | 3 (18.8) | 6 (37.5) | 7 (43.8) | ||

| Hookah non-smoker | 6 (8.1) | 46 (62.2) | 22 (29.7) | 16 (21.6) | 45 (60.8) | 13 (17.6) | ||

| Family history of obesity | 0.83 | 1.0 | ||||||

| With family history of obesity | 8 (12.3) | 38 (58.5) | 19 (29.2) | 13 (20) | 37 (56.9) | 15 (23.1) | ||

| Without family history of obesity | 2 (8.3) | 16 (66.7) | 6 (25) | 5 (20.8) | 14 (58.3) | 5 (20.8) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 45.59 ± 7.23 | 42.05 ± 6.21 | 44.1 ± 7.77 | 0.21 | 42.16 ± 7.08 | 43.13 ± 6.89 | 43.62 ± 6.77 | 0.8 |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 94.9 ± 16.27 | 114.92 ± 54.23 | 123.2 ± 38.09 | 0.28 | 124.16 ± 40.12 | 112.6 ± 53.6 | 112.3 ± 37.73 | 0.64 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 153.6± 66.32 | 152.79 ± 60.57 | 178.36 ± 68.85 | 0.24 | 178.89 ± 61.67 | 162.5 ± 66.58 | 136.1 ± 53.95 | 0.1 |

| Total chol. (mg/dL) | 200.5 ±26.14 | 183.71 ± 42.44 | 195.48 ± 40.47 | 0.31 | 199.42 ± 47.37 | 187.46 ± 40.71 | 182.7 ± 32.49 | 0.41 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 44 ± 8.37 | 44.44 ± 10.36 | 42.78 ± 10.76 | 0.81 | 43.26 ± 11.31 | 43.8 ± 8.76 | 44.94 ± 12.54 | 0.87 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 128 ± 23.93 | 111.21 ± 36.06 | 120.96 ± 33.65 | 0.25 | 121.68 ± 39.35 | 114.63 ± 34.47 | 113.45± 30.30 | 0.7 |

FTO SNPs (rs1421085, rs17817449) and Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Obese Patientsa

PCR-RFLP assay for FTO rs17817449 (A) and rs1421085 (B) genotyping. In part A, M is a DNA size marker, UD is an undigested PCR product, line 1 is wild-type homozygote genotype (GG), line 2 is heterozygote genotype (GT), and line 3 is homozygote mutant genotype (TT). In part B, M is a DNA size marker, line 1 is a heterozygote genotype (CT), line 2 is a wild-type homozygote genotype (TT), and line 3 and 4 are mutant homozygote genotype (CC).

5. Discussion

Managing obesity with traditional methods has not been successful so far; therefore, preventing obesity is the most promising approach to deal with this public health challenge. Genetic knowledge-based approach contributes to finding individuals with a potential risk of obesity and obesity-related diseases. FTO is the most studied gene related to obesity. Many investigations have been conducted to evaluate the association between different polymorphisms of this gene and morbid obesity in populations of different ethnicities. Two of the polymorphisms are rs1421085 and rs17817449, which are located in the conserved regions. Therefore, they may have an effective role in the gene function (19, 24). Despite various investigations in different populations, to our knowledge there is still no study, which specifically investigates the association of these two SNPs (rs1421085 and rs17817449) with morbid obesity in the Iranian population. Therefore, this study was performed in order to investigate the correlation of the FTO genetic variations and obesity incidence in Iran. Our results indicated a significant association between rs1421085 and rs17817449 SNPs and obesity in southern Iran. No significant association was found between these SNPs and demographic and clinical characteristics of obese patients. In consistence with our findings, Dina et al., reported a strong association between FTO variants and morbid obesity in children and adults of European ancestry (19). Similar results were obtained by Villalobos‐Comparan et al., and Price et al., in Mexican (22) and American (23) populations, respectively. Other studies indicated a significant association between FTO variants and obesity-related phenotypes in French-Canadian (24), Portuguese children (28), Slavic Eastern European (29), Turkish (30), and Saudi (31) populations. In a meta-analysis study, Peng et al. indicated the association of moderate increased risk of obesity with five FTO gene SNPs (rs1421085, rs17817449, rs9939609, rs8050136, and rs112198) (32). Contrarily, some investigations displayed no association between FTO variants and obesity in populations of different ethnicities like Mexican children (33), Egyptian children and adolescents (34), and six oceanic populations (35). These contradictory findings may be due to different ethnicities and also different sample sizes in various studies. In conclusion, our findings indicated a significant association between two FTO SNPs (rs1421085, rs17817449) and increased risk of obesity. However, given that our sample size was not large enough to consider these genetic variations as potential biomarkers for obesity, further investigations in different populations with larger sample sizes are required.