1. Background

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neuropsychiatric disorder that gradually impairs memory and behavioral functions (1). The global prevalence of AD was estimated at 47 million people in 2015 and this rate is expected to approximately triple by 2050 (2, 3). AD features include amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). Amyloid plaques (deposits) are produced by the accumulation of Aβ proteins and neurofibrillary tangles created by the aggregation of hyper-phosphorylated Tao proteins (4, 5). Aβ is considered as the most toxic substance in the brain of AD patients (6). Thioflavin staining is the most suitable and standardized method for screening Aβ (7). Thioflavin-S is used for detecting Aβ plaques that can bind to distinctive β-pleated sheet of amyloid fibrils (8-11). Thioflavin-S results from methylation of dehydrothiotoluidine with sulfonic acid (12). In addition, monoclonal mouse antibodies are increasingly employed to detect amyloid deposits. Different mechanisms are presented for Aβ accumulation such as elevated synthesis and high propensity for aggregation (13). Thus, approaches to prevent and reduce Aβ deposition are mainly examined as therapeutic strategies for AD treatment (14, 15).

Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) are an appropriate source of stem cells in clinical studies as these cells can be achieved via liposuction or from subcutaneous adipose tissues (16-18). hADSCs are the most suitable stem cells due to their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, migrating to the damaged sites of the brain without any ethical concerns, immune rejection or tumorigenesis (19). This is the first attempt to use Immuno- and Thioflavin S-costaining to evaluate Aβ plaques in a rat model of AD following intravenous injection of hADSCs. Regarding the previous investigations, there is a scarcity of reports on using this technique for evaluating Aβ plaques after stem cell injection.

2. Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Aβ (1-42), DMEM, DiI, Thioflavin-S and DAPI stains were supplied from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ketamine (Alfasan, Holland) and Xylazine (Pantex Holland B.V.) were utilized for anesthesia before surgery. Anti-Aβ antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Other chemicals in this research were supplied from commercial sources.

2.2. Animals

In this study, we used 32 male Wistar rats weighing 250 - 320 gr. The rats were purchased from the animal house of Iran University of Medical Sciences. The animals were kept under standard conditions with a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 25°C. Normal rat chow and water were provided ad libitum. All the experiments were performed under the standard guidelines for the use and care of laboratory animals approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (90/11/5931).

2.3. Experimental Design

Animals were randomly divided into four groups of eight as follows: control group: The rats did not undergo any surgery or injection; sham group: The Hamilton syringe (without any medication) was entered to the hippocampus of the rats by stereotaxic surgery; Alzheimer's model (AD) group: The rats received Aβ injection in their hippocampus through stereotaxic surgery; and stem cell treatment group (AD + Sc): The rats received 3 × 106 hADSCs by intravenous administration three weeks after intra-hippocampal Aβ injection.

2.4. Aβ Preparation and Surgery

Lyophilized peptide powder of Aβ1-42 was dissolved in sterile water to reach the final concentration of 2 mmol/L. The final solution was incubated for 48 hours at 37°C. Anesthesia was induced by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of ketamine hydrochloride (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg). Afterwards, the rats were located in the stereotaxic frame (Stoelting Co, USA). Each animal received 5 μL of Aβ injection in the right and left CA1 hippocampus (each side 5 μL) (AP: 3.8, ML: 2.4, DV: 2.9) according to the Paxinos and Watson Atlas (20).

2.5. Isolation and Culture of hADSCs

hADSCs were separated from adipose tissues obtained from the abdominal superficial layers of 25 to 45-year-old patients during liposuction in the operation room of Rasoul-e-Akram General Hospital, Tehran, Iran. hADSCs were isolated according to the protocol of Dubois et al. (21). For removing blood vessels, adipose tissue was washed in 1% P/S solution, and 0.1% collagenase and 1.0% bovine serum albumin (BSA) were added. The cell pellets were washed with PBS, centrifuged, suspended in DMEM /F12 culture medium (10% fetal bovine serum [FBS] and 1% P/S) and incubated (37°C, 5% CO2, 98% moisture) until the fifth passage.

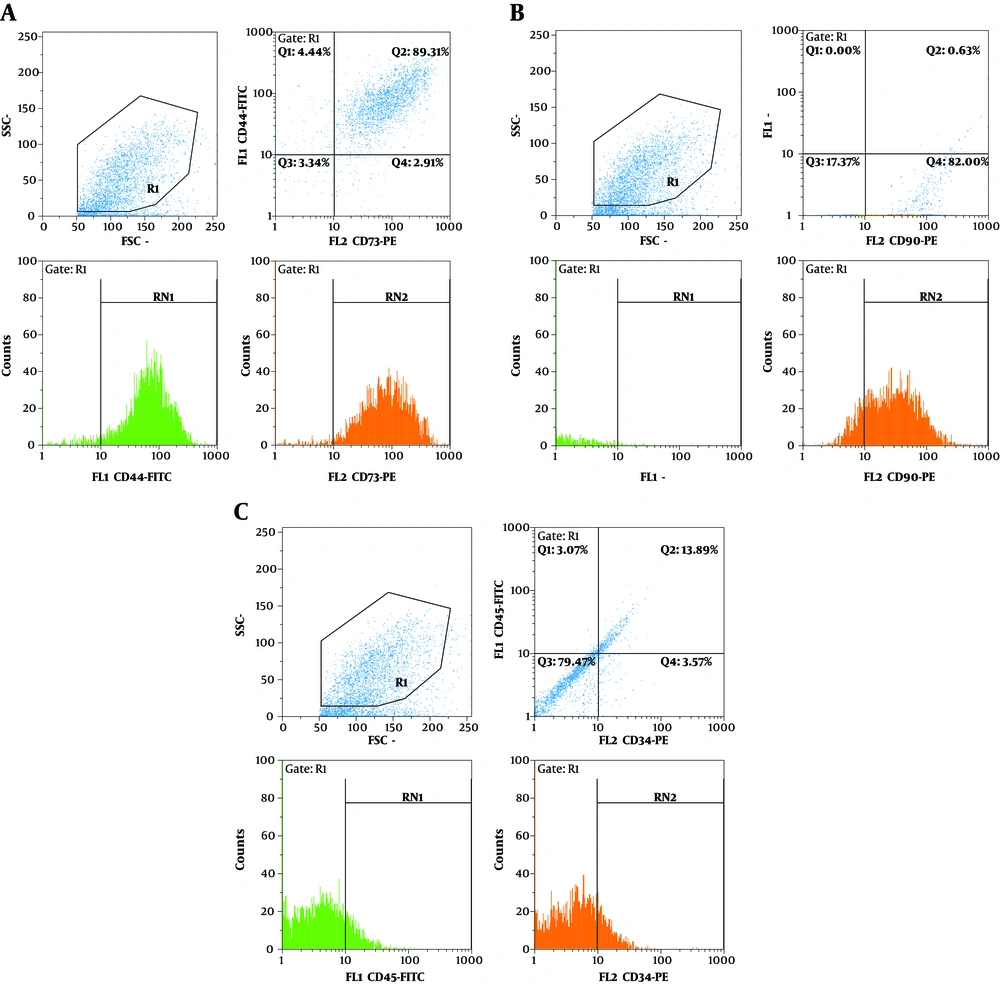

2.6. hADSCs Characterization

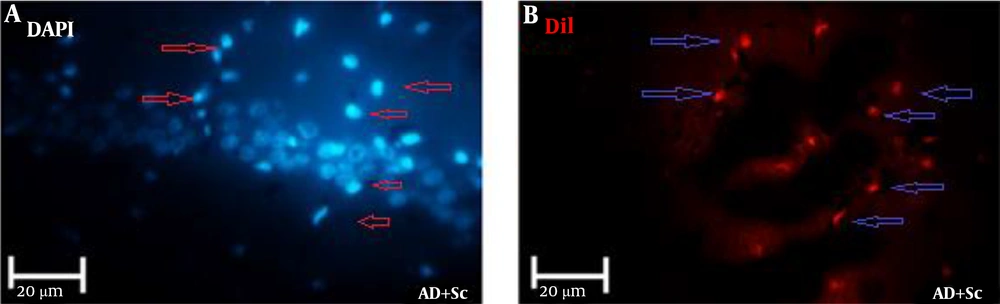

For characterization of hADSCs, flow cytometry was used according to a previous study (22). Cells were incubated with anti-CD44, anti-CD90, anti-CD73 (conjugated to FITC), anti-CD34 and anti-CD45 (conjugated to PE) for 30 minutes. The cells in the 5th passage were labeled with DiI. 106 cells were suspended in 1 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and then 5 μL of DiI solution (50 μg DiI powder solved in 50 μL DMSO) was added.

2.7. Immuno- and Thioflavin S-costaining

Three months after hADSCs injection, the rats were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine, perfused by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L PBS (pH = 7.4). The brains were taken out and fixed for 24 hours in 10% formalin solution. Coronal sections were prepared at 5 μm thickness by microtome after routine paraffin processing.

For immunofluorescent staining, brain sections were processed according to the regular protocols (23). Briefly, the sections were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 20 minutes and immunostained with the application of 1:100 dilution of primary anti-Aβ rabbit polyclonal antibody followed by goat anti-rabbit FITC-conjugated secondary antibody at 1:200 dilution. Thereafter, the sections were put in 10% formalin for 10 minutes and rinsed in PBS. The sections were incubated in 0.25% potassium permanganate (10 minutes), and then washed in PBS, incubated in 2% potassium metabisulfite and 1% oxalic acid until they seemed white. Then, the sections were washed in water and stained for 10 minutes with a solution of 0.015% Thioflavin-S in 50% ethanol and water. After drying the sections, they were immersed into Histo-Clear (24). DAPI was used for counterstaining the nuclei. The sections were mounted on slides and evaluated under fluorescence microscope (Labomed microscope equipped with an Invenio 6EIII camera).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed by using the Graph pad Prism program (GraphPad software, Inc. USA). We used One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Data are presented as Mean ± SEM (standard error of mean). P-value less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. hADSCs Characterization

hADSCs showed positive staining for the specific mesenchymal surface markers CD73, CD44 (Figure 1A) and CD90 (Figure 1B). hADSCs indicated high levels of CD73, CD44 and CD90, which were expressed in 92.28%, 93.65% and 83.5% of the total cell population, respectively. However, a small proportion of hADSCs represented hematopoietic stem cell surface markers, as well as CD34 and CD45, which were expressed in 18.67% and 16.45% of cells, respectively (Figure 1C).

3.2. Homing of hADSCs

As shown in Figure 2, hADSCs that were labeled DiI migrated from the site of delivery to the CA1 region of the hippocampus (DiI-labeled hADSCs = red and DAPI-stained nuclei = blue).

3.3. Immuno- and Thioflavin S-Costaining

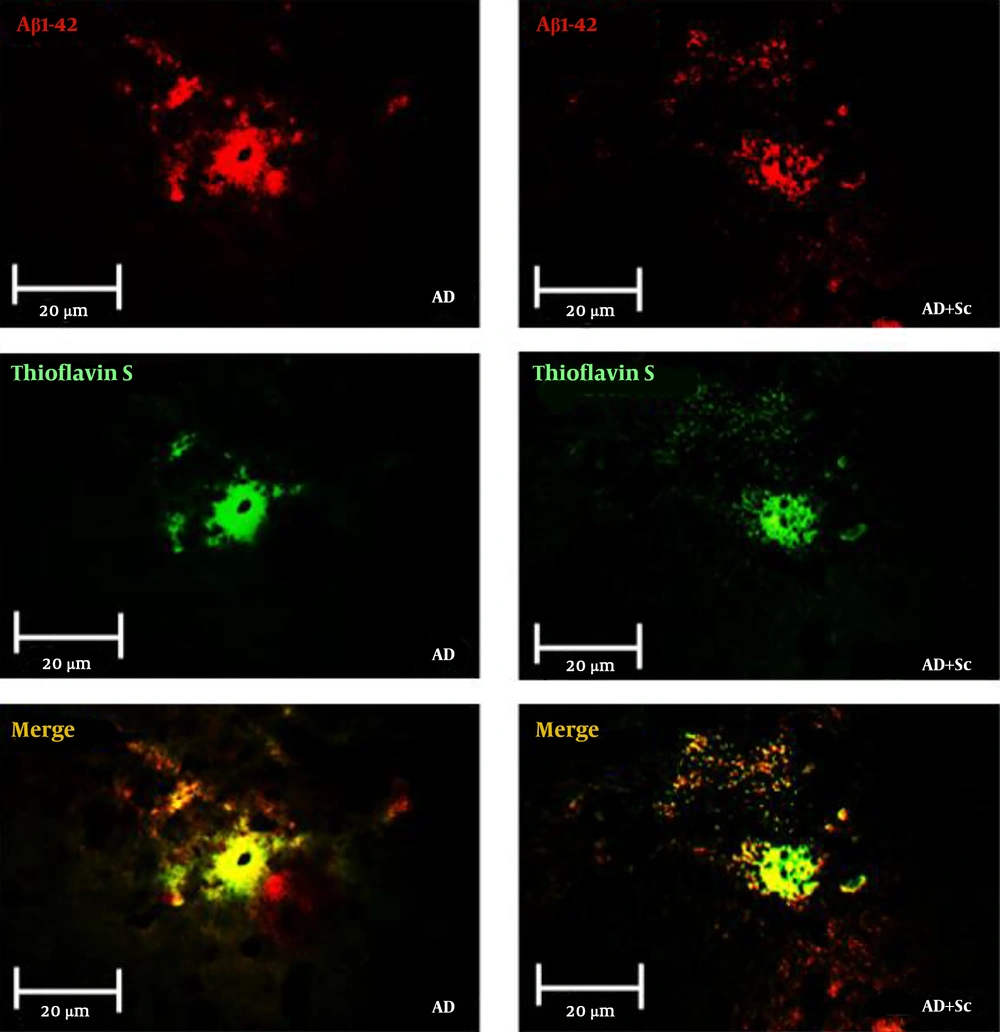

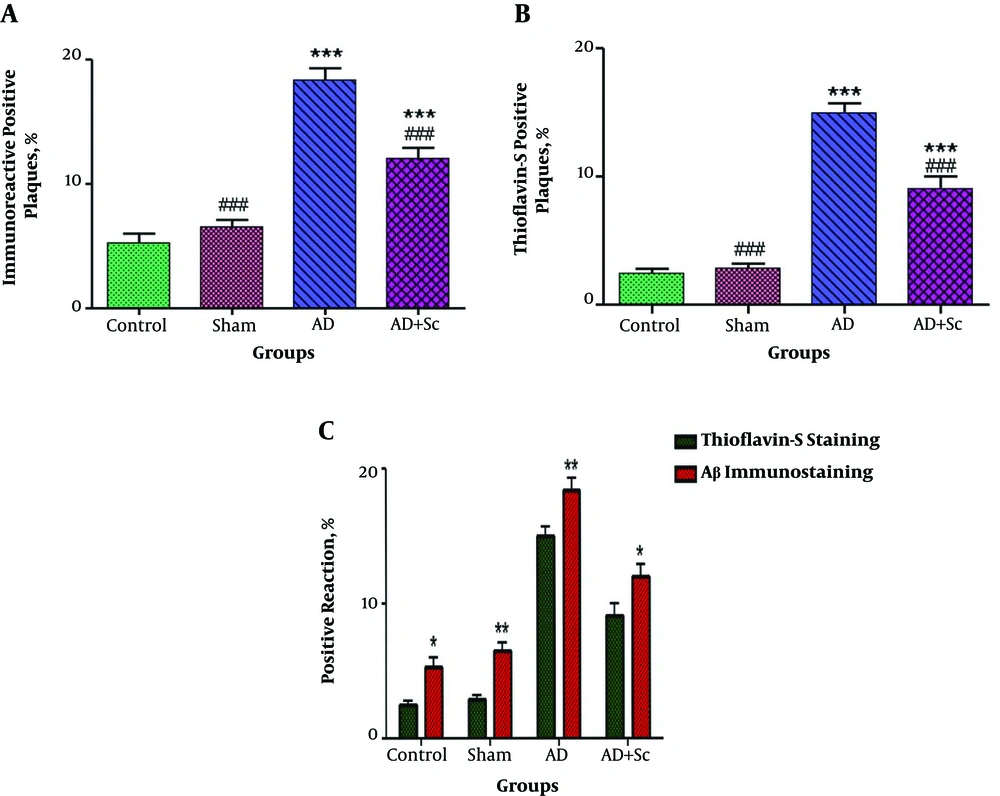

Figure 3 shows immunofluorescent double staining of primary anti-Aβ rabbit polyclonal antibody followed by goat anti-rabbit FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (red), Thioflavin-S staining (green) and merge picture (yellow) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in the AD and AD + Sc groups. Data showed more distinct Aβ immunoreactivity and Thioflavin-S stain in the AD group compared to the treatment group. Statistical analysis revealed that there was no significant difference in immunoreactive positive plaques between the control and sham groups, but these plaques increased significantly in the AD group relative to the control and sham groups (***P-value < 0.001). Nonetheless, the administration of hADSCs significantly decreased immunoreactivity positive plaques in the AD group (###P-value < 0.001; Figure 4A).

Immunoreactive positive plaques in different groups (values are expressed as mean ± SEM). N = 6, ***P < 0.001 different from control group, ###P < 0.001 different from Aβ group (A), N = 6, ***P < 0.001 different from control group, ###P < 0.001 different from Aβ group (B), *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 show significant difference between Aβ immunostaining compared to Thioflavine-S staining (C).

The number of Thio-S-positive plaques was not significantly different between the control and sham groups; however, the number of Thio-S-positive plaques increased significantly in the AD group compared to the control and sham groups (***P-value < 0.001). Intravenous injection of hADSCs significantly decreased the number of Thio-S-positive plaques in the AD group (###P-value < 0.001; Figure 4B).

In this research, we also investigated Aβ plaques in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in different groups using Aβ immunostaining compared to Thioflavin-S staining.

As shown in Figure 4C, we found that the plaques detected by anti-Aβ antibody were significantly more than those distinguished by Thioflavin-S in all the groups. The results showed the significant effect of staining method (F (1, 40) = 42.48, P < 0.0001) and groups (F (3, 40) = 144.58, P < 0.0001) on the positive Aβ plaques in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. However, the interaction of these two factors was non-significant (F (3, 40) = 0.15, P = 0.928).

4. Discussion

The first neuropathological criterion for the diagnosis of AD is the aggregation of Aβ peptides that can form plaques. These plaques are toxic to neurons and lead to apoptosis and synaptic loss. Upregulated neuroinflammatory factors and loss of synaptic markers can lead to AD progression by causing cognitive disturbances (25-29). Immunofluorescent staining using anti- Aβ antibody can detect Aβ plaques in a rat model of AD. Additionally, Thioflavin-S staining technique is utilized for the detection of plaques (9). In our study, AD model was confirmed by histological analysis, while Thioflavin-S and immunoreactive positive plaques increased significantly in the AD group compared to the control group.

Our study showed that Aβ plaques as toxic elements increased in the AD group. These results are consistent with a previous report about staining of Aβ in AD. That report showed that Aβ immunohistochemical staining could detect both fibrillar and non-fibrillar Aβ, whereas Thioflavin-S identified β-pleated fibrillar amyloids (30). We also observed that the plaques detected by anti-Aβ antibody were significantly more than those distinguished by Thioflavin-S in all the groups (comparison of staining methods). It may be related to the detection of both fibrillar and non-fibrillar Aβ by immunohistochemical staining (anti-Aβ antibody) compared to the detection of fibrillar Aβ by Thioflavin-S staining. There are achievable therapeutic strategies for AD aiming to prevent and reduce Aβ deposits (14). Stem cell transplantation has been reported to prevent cell death by reducing Aβ deposits in neurodegenerative disorders.

Studies have shown that stem cells could increase synaptic density mainly through elevated secretion of neurotrophic and growth factors, which play an important role in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases (16, 31, 32). This was the first attempt to measure the amount of Aβ deposits by Immuno- and Thioflavin S-costaining in a rat model of AD following hADSCs intravenous administration.

We found that after the migration of stem cells to the hippocampus of AD rats, a significant decrease in fluorescence intensity of Thioflavin-S and Aβ expression level was observed in the hADSCs treatment group, showing the effective role of hADSCs in decreasing amyloids aggregation. It seems that hADSCs as therapeutic targets apply neuroprotective effects related to Aβ clearance. A previous research showed that Aβ synthesis blockade is not effective in decreasing Aβ levels compared to Aβ clearance (33). Investigations showed that mesenchymal stem cells significantly enhanced neuronal survival against Aβ toxicity in AD models (34). hADSCs could induce endogenous microglial activation, which led to removing Aβ aggregates in AD animal models (35). Furthermore, bone marrow-derived cells could differentiate into functional microglia and cause Aβ clearance as a therapeutic effect (36). Further in-depth studies are still necessary to clarify the detailed mechanisms.

4.1. Conclusions

Our results indicated that hADSCs served an effective role in decreasing amyloid aggregation by using Immuno- and Thioflavin-S-costaining. As Aβ toxicity is the major reason for neuronal death in AD, hADSCs may be a promising candidate for AD therapy due to their high potential for clearance of Aβ deposits.