1. Background

The Brachial Plexus Block (BPB) is frequently employed in creating proximal arm arteriovenous fistula (AVF) (1). The technique employed for BPB in upper limb surgeries varies depending on the Brachial Plexus availability, with options including neurostimulation, Ultrasound (US), and trans-arterial methods (2). Supraclavicular brachial plexus block (SCPB) is an alternative to traditional BPB techniques, offering comparable anesthesia and postoperative analgesia with a diminished adverse events incidence (3). However, SCPB does not afford complete anesthesia to the arm medial side, which is innervated by the intercostobrachial nerve (ICBN) and the brachial cutaneous nerve medial branch (2). As a result, local anesthetic (LA) supplementation intraoperatively may be necessary to avoid switching to general anesthesia (4). The ICBN can be blocked using two methods: (1) LA can be injected along the nerve pathway for selective ICBN blockade using US guidance; or (2) by relying on the superficial anatomy of the nerve for precise placement (5). Using US guidance, ICBN can be recognized and blocked separately or in combination with other nerves (6). Ultrasound -guided ICBN blockade has been proposed as a logical solution for controlling pain induced by the closure of the tourniquet in the upper extremities (7). The serratus plane block (SPB) is a regional anesthesia approach primarily employed in the thoracic region (8). By targeting the thoracic intercostal nerves, SPB provides adequate anesthesia as well as analgesia for the hemithorax, posterior shoulder, and axillary region (9). We hypothesized that US-guided ICNB and SPB would provide superior postoperative analgesia as opposed to traditional landmark-guided ICNB following SCPB for AVF creation in the medial side of the arm.

2. Objectives

The present work compared the role of US-and landmark-guided ICBN and SPB when added after SCPB to determine which technique most effectively covers the medial side of the arm, an area often spared by SCPB alone, during AVF creation.

3. Methods

This randomized, double-blind trial was performed on 75 patients, both sexes, aged 18 - 65 years, with physical status classified as III according to the American Society of Anesthesiology and experiencing creation of an AVF in the arm’s medial side. This research was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (NO: 36264PR77/5/24) between July 2024 and December 2024. This investigation adhered strictly to the ethical standards set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki. Every participant granted written informed consent before joining the study. In keeping with transparency and regulatory best practices, the trial was formally registered on ClinicalTrials.gov prior to enrolling any patients (NCT06500572). Participants were excluded if they had drug allergies, a Body Mass Index of 35 kg/m² or more, coagulation abnormalities, severe heart, kidney, and liver diseases, pregnancy, vasculitis, unstable hemodynamics, upper extremity neuropathy, mental illness, or seizures. Prior to the surgical procedure, all participants underwent medical history taking, clinical examination, and laboratory testing. Furthermore, they were familiarized with the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain assessment to ensure that they could accurately report their level of pain.

3.1. Randomization and Blinding

A random allocation process using computer-generated numbers (https://www.randomizer.org/) was employed to ensure the integrity of the research. All participants’ codes were placed in an opaque, closed envelope to maintain blinding. Participants were randomized equally into three groups (1:1:1 ratio) receiving single SCPB followed by either traditional landmark LCBN (TICBN) in group T, US-guided ICBN in group U, or US-guided SPB in group S. To maintain the blinding, both patients and outcome assessors were blind to group assignments. All blocks were performed by a single experienced anesthesiologist not involved in outcome assessment, ensuring consistency and minimizing performance bias. Standard monitoring in this research included temperature probe, ECG, pulse oximetry, and non-invasive blood pressure. The nerve blocks were administered using a US machine (Philips CX50, extreme edition, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) with a linear probe (6 - 12 MHz) under strict aseptic conditions. Lidocaine 1% was injected at the entry site of the needle. After confirming the needle's location with 1 mL of saline solution, 20 mL of bupivacaine (0.25%) was administered.

3.2. Supraclavicular Plexus Block Procedure

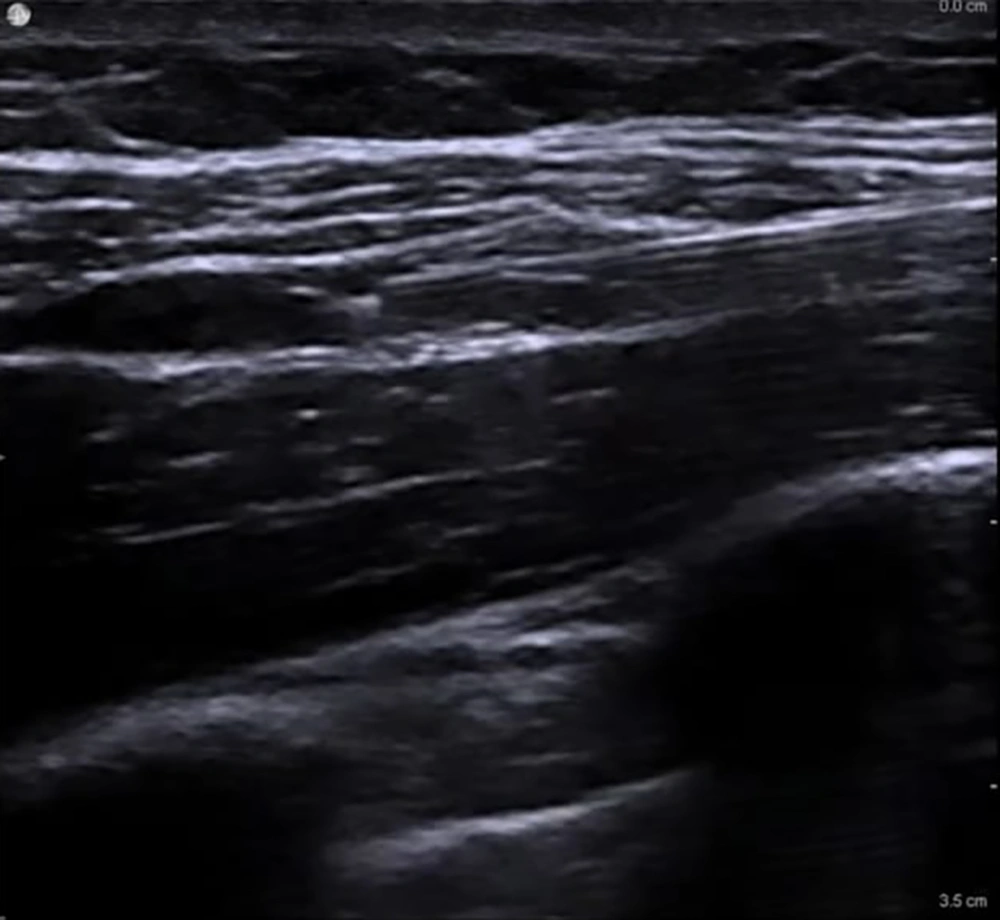

In all patients, the SCPB was performed before the assigned supplemental block (10). Patients were placed supine with the head turned approximately 30° away from the surgical side and a small towel positioned between the scapulae to optimize access. After aseptic preparation, a high-frequency linear US probe (6 - 12 MHz) covered with a sterile sheath was placed in the coronal-oblique plane just superior to the clavicle and lateral to the sternocleidomastoid muscle to visualize the subclavian artery medially, the brachial plexus divisions as a cluster of hypoechoic round structures lateral to the artery, and the first rib and pleura as hyperechoic lines deep to the artery. Using an in-plane lateral-to-medial approach, a 22-G, 80-mm insulated block needle was advanced under continuous US guidance toward the “corner pocket” bordered by the subclavian artery medially, the first rib inferiorly, and the brachial plexus laterally. After negative aspiration, 5 - 10 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was injected into the corner pocket, and the needle was redirected to deposit additional 3 - 5 mL aliquots around the remaining plexus divisions to ensure circumferential spread, for a total of 20 mL. Proper injectate distribution was confirmed sonographically, and care was taken to avoid pleural puncture, vascular injection, or intraneural spread (Figure 1).

3.3. Traditional Landmark Intercostobrachial Nerve Block Procedure

In group T, following the SCPB, the intercostobrachial nerve (ICBN) was blocked using a traditional landmark-guided technique (2). The patient was positioned supine with the ipsilateral arm abducted to 90°. The second rib was palpated along the midaxillary line, and the injection point was marked approximately 2 cm inferior to its diminished border. After skin antisepsis, an 80-mm block needle was inserted perpendicular to the skin until gentle contact with the rib was made. The needle was then redirected slightly caudally to slip off the inferior edge, avoiding the intercostal neurovascular bundle. A total of 5 - 8 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was injected in a fan-shaped manner along the rib, supplemented by subcutaneous infiltration extending anteriorly and posteriorly for 3 - 5 cm to cover the ICBN and its communicating branches.

3.4. Ultrasound-Guided Intercostobrachial Nerve Block Procedure

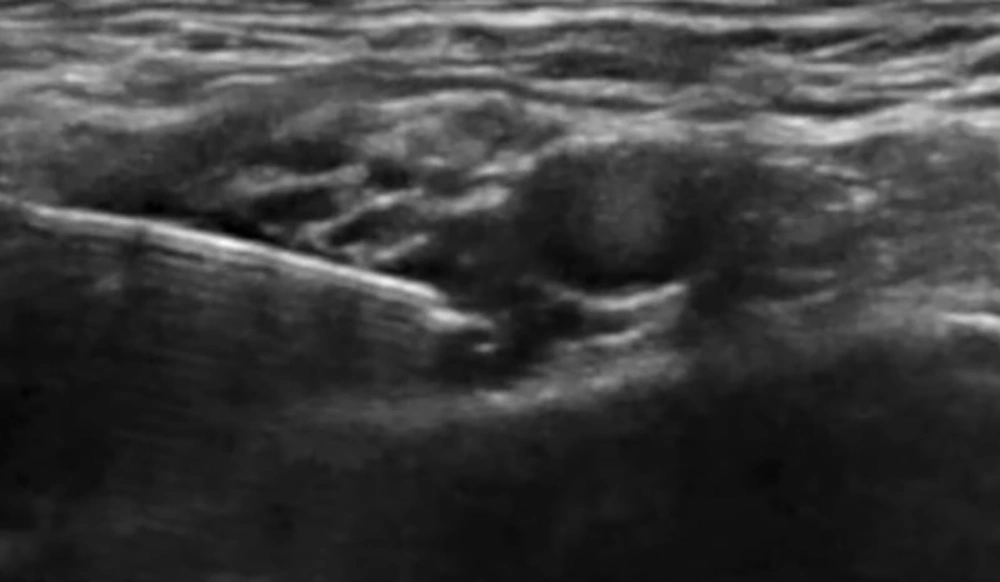

In group U, after SCPB, the ICBN was blocked under US guidance at the midaxillary level. The patient was positioned supine with the arm abducted to 90° (11). A high-frequency linear probe (6 - 12 MHz) was placed transversely over the midaxillary line at the level of the 2nd–3rd intercostal spaces. The axillary vein and artery were first visualized, then the probe was adjusted superficially to identify the fascial plane between the subcutaneous tissue and the serratus anterior muscle. The ICBN appeared as a small hyperechoic oval or linear structure within this plane. Using an in-plane, posterior-to-anterior needle approach, an 80-mm block needle was advanced into the fascial plane. After confirming negative aspiration, 5 - 8 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was slowly injected, and real-time sonographic imaging confirmed the spread of local anesthetic along the plane both anteriorly and posteriorly (Figure 2).

3.5. Serratus Plane Block Procedure

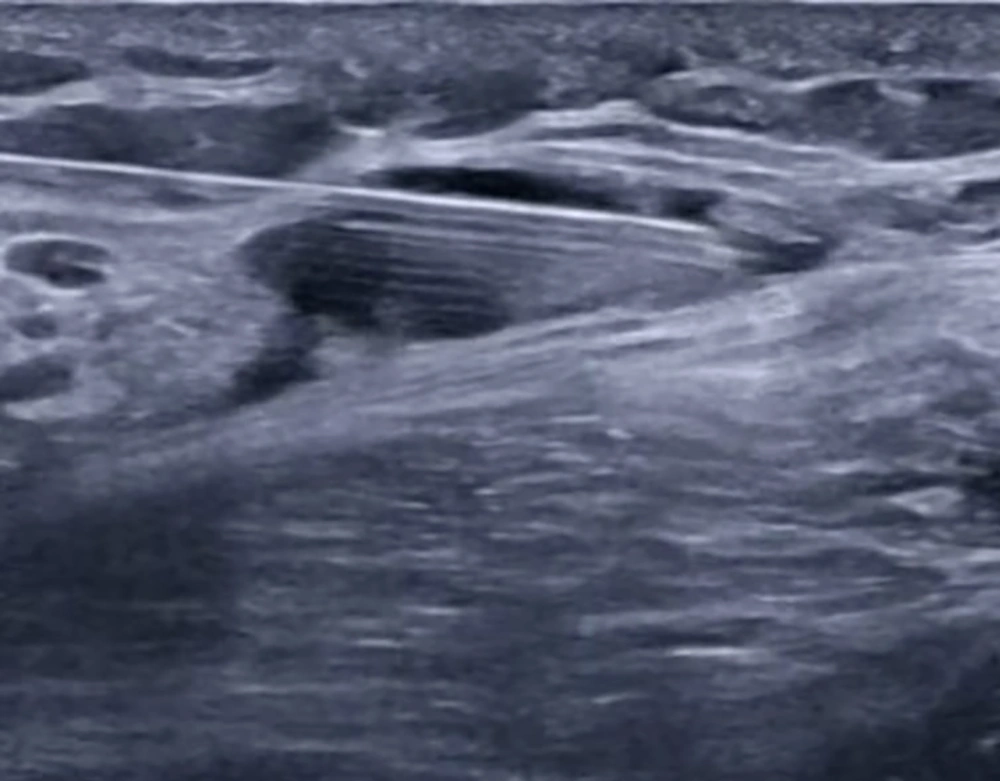

In group S, following completion of the SCPB, the SAP block was performed with the patient in the lateral decubitus position, operative side up, and the ipsilateral arm abducted to expose the midaxillary region (12). A high-frequency linear US probe (6 - 12 MHz) was positioned over the midaxillary line at the level of the 4th–5th ribs, identifying the latissimus dorsi (LD) muscle superficially and posteriorly, the serratus anterior (SA) muscle deep to LD, and the underlying ribs and pleura. Using an in-plane posterior-to-anterior approach, an 80-mm block needle was advanced under continuous US guidance into the fascial plane between the LD and SA muscles (superficial SAP). After confirming negative aspiration, 20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was injected incrementally, with hydrodissection confirming correct placement and real-time imaging verifying spread of local anesthetic along the plane in both cranial and caudal directions to ensure adequate coverage (Figure 3).

If pain persisted during the operation, repeated local anesthetic infiltration (2% lidocaine, maximum dose 20 mL) was administered. If pain continued after regional anesthesia, the patient was converted to general anesthesia. A standardized postoperative analgesic regimen was implemented. Paracetamol 1 g was administered every 6 hours for patients on regular dialysis and every 8 hours for those not on dialysis. Fentanyl was employed as the rescue analgesic due to its safer profile in renal impairment, administered intravenously in 25 - 50 mcg boluses as needed if the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score exceeded 3, with repeat doses permitted until the score dropped below 4. Pain was assessed at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 hours postoperatively. Adverse effects were monitored, including hypotension (defined as MAP < 65 mmHg or a reduction by 20% as opposed to basal, which was managed with IV fluids; bradycardia (defined as less than 50 beats/min), managed with IV atropine at 0.02 mg/kg; respiratory depression (SpO2 < 95% requiring oxygen supplementation); postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), managed with ondansetron at 0.1 mg/kg IV; and any complications related to the nerve block. Patient satisfaction was evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale, where (1) Extremely dissatisfied, (2) unsatisfied, (3) neutral, (4) satisfied, and (5) extremely satisfied (13). The research's primary outcome was the percentage of patients who needed LA supplementation, while secondary outcomes encompassed total fentanyl consumption in the first 24 hours and patient satisfaction.

3.6. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was determined utilizing G*Power 3.1.9.2 (Universität Kiel, Germany). Pilot research was conducted with five cases per group, revealing that 40% of patients needed local anesthesia supplementation with landmark techniques, while 10% required it with US guidance. The determination of the sample size was influenced by several key factors: A 95% confidence limit, 80% power, a 2:1 group ratio, and the inclusion of eight additional cases to accommodate potential dropouts. In total, 75 individuals were enrolled in this research.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

The data was analyzed using SPSS v27, which was developed by IBM and is located in Chicago, IL, USA. To check whether the data was distributed normally, we employed histograms and the Shapiro-Wilks test. We employed analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc test to examine quantitative parametric data, which was presented as means with standard deviations (SD). Medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) were employed to depict quantitative non-parametric data, and the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests were employed to compare groups. The Chi-square test was employed to summarize the qualitative variables as frequencies (%). A two-tailed P of less than 0.05 was employed to define statistical significance.

4. Results

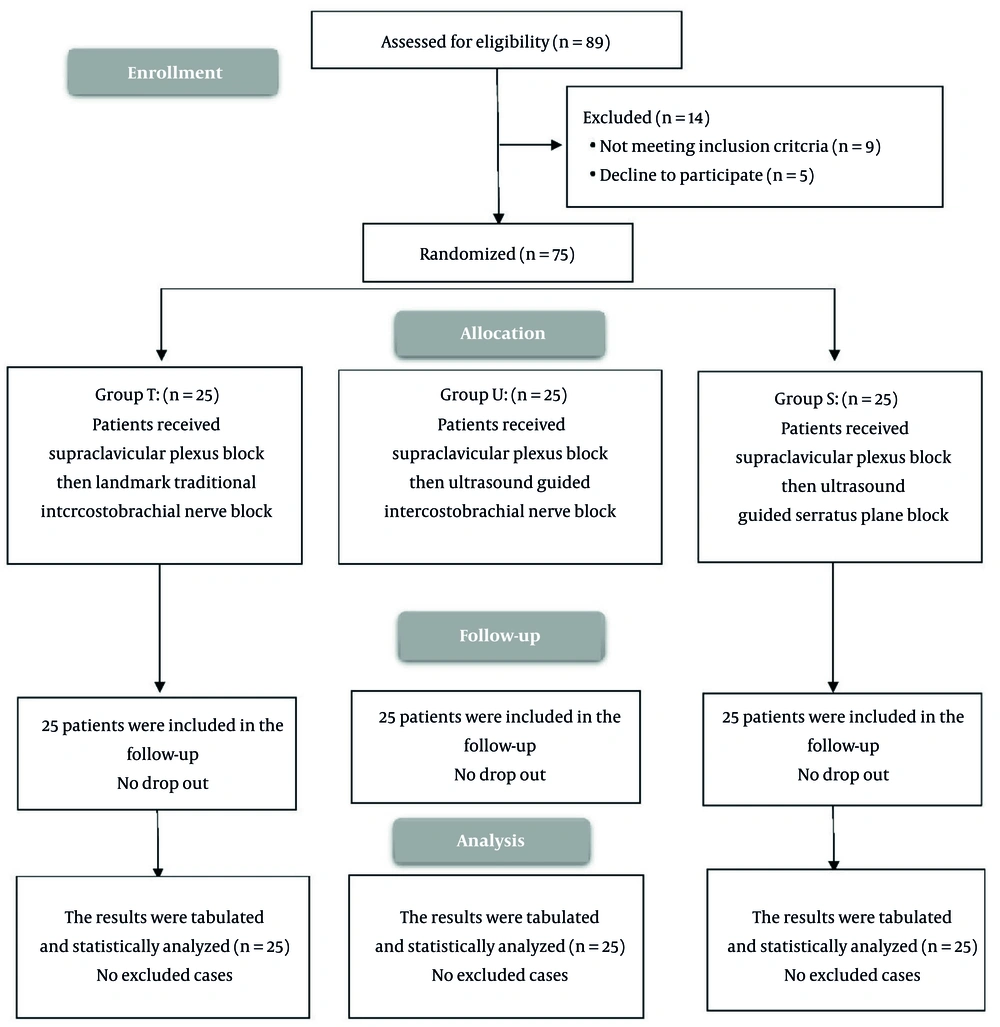

We enrolled 89 cases and evaluated their eligibility for participation. Of these, nine patients did not meet the inclusion criteria, and five declined to participate, leaving 75 patients randomized equally to three groups and followed for analysis (Figure 4).

Demographic data and surgery duration were comparable among the groups studied (Table 1).

| Variables | Group T | Group U | Group S | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 42.2 (10.95) | 43.7 (10.6) | 39.6 (9.7) | 0.373 |

| Sex, n | ||||

| Male/female | 15/10 | 13/12 | 14 /11 | 0.850 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.6 (9.95) | 74.4 (7.55) | 72.9 (8.78) | 0.158 |

| Height (m) | 1.7 (0.08) | 1.68 (0.08) | 1.7 (0.07) | 0.785 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 (4.05) | 26.4 (3.66) | 25.4 (3.47) | 0.250 |

| ASA physical status (No.) | ||||

| I/II | 16 /9 | 14/10 | 17 /8 | 0.780 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 83.6 (15.51) | 81.6 (16.5) | 87.4 (13.78) | 0.401 |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

a Values are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

The proportion of patients requiring LA supplementation was notably reduced in groups U (8%) and S (12%) when compared with group T (44%) (P < 0.05), and the rates in groups U and S were similar. The duration until the first rescue analgesia was notably extended in groups U and S, as opposed to group T, and in group U relative to group S (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the overall fentanyl usage during the first 24 hours was notably reduced in groups U and S as opposed to group T, with group U exhibiting diminished consumption than group S (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

| Variables | Group T | Group U | Group S | P-Value b | Post hoc b, c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who needed LA supplementation (No.) | 11 (44) | 2 (8) | 3 (12) | 0.002 | P1 = 0.008, P2 = 0.025, P3 = 1 |

| Time of first rescue analgesia (h) | 2.9 (0.93) | 9.8 (1.46) | 7.4 (1.11) | < 0.001 | P1 < 0.001, P2 < 0.001, P3 < 0.001 |

| Total fentanyl consumption in the 1st 24h (mcg) | 59 (15.94) | 38 (12.75) | 49 (5) | < 0.001 | P1 < 0.001, P2 < 0.001, P3 < 0.001 |

Abbreviation: LA, local anesthesia.

a Values are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

b P < 0.05 is statistically significant.

c P1, P between group I and group II; P2, P between group I and group III; P3, P between group II and group III.

The VAS scores indicated no significant differences among the groups at 0, 12, and 24 hours. VAS scores were notably reduced by 2 and 4 hours in groups U and S as opposed to group T (P < 0.05), and were similar between groups U and S. At the 8-hour mark, VAS scores were notably reduced in groups T and U when as opposed to group S (P < 0.05), while the scores in groups T and U were like each other (Table 3).

| Variables | Group T | Group U | Group S | P-Value b | Post hoc b, c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0h | 1 (1 - 1) | 1 (0 - 1) | 1 (0 - 1) | 0.059 | |

| 2h | 3 (2 - 5) | 2 (1 - 3) | 2 (2 - 3) | 0.002 | P1 < 0.001, P2 = 0.022, P3 = 0.270 |

| 4h | 3 (2 - 5) | 2 (1 - 3) | 2 (1 - 3) | 0.012 | P1 = 0.008, P2 = 0.013, P3 = 0.879 |

| 8h | 3 (1 - 4) | 2 (1 - 4) | 3 (3 - 6) | 0.002 | P1 = 0.333, P2 = 0.013, P3 < 0.001 |

| 12h | 3 (2 - 4) | 2 (2 - 4) | 3 (2 - 4) | 0.207 | P1 < 0.001, P2 < 0.921, P3 < 0.001 |

| 24h | 3 (1 - 4) | 3 (2 - 4) | 3 (2 - 4) | 0.810 |

Abbreviation: VAS, visual analogue scale.

a Values are presented as median (IQR).

b P < 0.05 is statistically significant.

c P1, P between group I and group II; P2, P between group I and group III; P3, P between group II and group III.

Group U exhibited a significantly higher level of patient satisfaction in comparison to groups T and S (P = 0.002). The occurrences of bradycardia, hypotension, and postoperative nausea and vomiting were comparable across the groups. No instances of pneumothorax, LAST, or respiratory depression were observed in any of the groups (Table 4).

| Variables | Group T | Group U | Group S | P-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient satisfaction | 0.002 b | |||

| Extremely satisfied | 0 (0) | 8 (32) | 2 (8) | |

| Satisfied | 4 (16) | 10 (40) | 8 (32) | |

| Neutral | 12 (48) | 6 (24) | 9 (36) | |

| Unsatisfied | 9 (36) | 1 (4) | 6 (24) | |

| Extremely dissatisfied | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Complications | ||||

| Bradycardia | 1 (4) | 4 (16) | 3 (12) | 0.376 |

| Hypotension | 2 (8) | 6 (24) | 4 (16) | 0.304 |

| PONV | 5 (20) | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | 0.220 |

| Pneumothorax | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Local anesthetic systemic toxicity | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Respiratory depression | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

Abbreviation: PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting.

a Values are presented as No. (%).

b P < 0.05 is statistically significant.

5. Discussion

The main observations from this research indicated that the time to 1st rescue analgesia was significantly prolonged in groups U and S as opposed to group T, and longer in group U in contrast with group S. Total fentanyl consumption in the 1st 24 hours was significantly reduced in groups U and S as opposed to group T, and diminished in group U in contrast with group S. The significantly delayed time to first rescue analgesia in the US-guided cohorts (U and S) as opposed to the landmark-guided group (T) further supports the hypothesis that these techniques offer superior pain relief. The choice of a superficial SAPB was based on its anatomical capacity to block the lateral cutaneous branches of the intercostal nerves supplying the medial arm, making it a suitable adjunct to SCPB for AVF creation. Its superficial approach also minimizes the risk of pleural injury (8). Supraclavicular plexus block alone may inadequately cover the medial arm because it spares the ICBN (14, 15). Supplementation with either the ICBN block or the SAPB can improve coverage. To the best of our knowledge, there are currently no published studies directly comparing the role of US-guided and landmark-guided ICBN and SPB following SCPB for anesthesia in AVF creation on the medial side of the arm. In our study, the number of patients requiring LA supplementation was significantly diminished in groups U and S as opposed to group T, with no significant difference between groups U and S. Ultrasound guidance enables more precise nerve localization and potentially more effective blocks than landmark techniques (16), which may contribute to reduced postoperative opioid requirements and improved pain control (17). The SPB has been shown to provide analgesia to the thoracic wall and axillary region, which may overlap with the area innervated by the ICBN (18, 19). Intercostobrachial nerve, performed at the level of the 3rd rib, can achieve complete sensory block in most cases and is effective in reducing the need for general anesthesia, providing faster onset of analgesia, and lowering rescue analgesic requirements (20-22). Intercostobrachial nerve, performed at the level of the 3rd rib, can achieve complete sensory block in most cases and is effective in reducing the need for general anesthesia, providing faster onset of analgesia, and lowering rescue analgesic requirements (23, 24). Our findings are in line with previous studies reporting that US guidance improves the accuracy and efficacy of nerve blocks, leading to better analgesia outcomes, Bhatia and co-authors (25), Chitnis and co-authors (26) and Magazzeni and co-authors (14). Siamdoust and co-authors (15) also demonstrated that ICBN effectively controls tourniquet pain following axillary block, with US guidance increasing block success and safety. Demir and co-authors (9) exhibited that total opioid consumption in the 1st 24h was significantly reduced in group SPB in contrast with the control group. However, Magoon and co-authors (27) found that in post-thoracotomy analgesia in cardiac surgeries, the time of the first rescue analgesia was significantly delayed in group SPB, in contrast with group US-guided ICBN. Total opioid consumption in the first 12h was significantly diminished in group S in comparison with group U. This variation might be related to utilizing a different LA since they gave 2.5 mg/kg of 5% ropivacaine. In our research, VAS was significantly diminished at 2 and 4h in groups U and S, in contrast with group T. The VAS decreased considerably at the eighth grade in groups T and U, in contrast to group S, and showed no significant difference between groups T and U. Similarly, Demir and co-authors (9) found that VAS was significantly decreased in group S in contrast with the control group. Also, Kim et al. (28) noticed that after single-port video-assisted thoracoscopic surgeries, the pain score was comparable between group T and S. Additionally, Öksüz and co-authors (29) demonstrated that VAS scores were recognized to be significantly improved in the S group in comparison to T group. Moreover, patient satisfaction ratings in our research varied significantly, with group U expressing greater satisfaction than groups T and S. The choice of anesthetic technique can influence the overall patient experience. High patient satisfaction is often correlated with effective pain management and reduced reliance on opioid analgesics (30). Therefore, implementing US-guided techniques could enhance patient satisfaction in surgical settings. Demir and co-authors (9) reported the same of our findings as they noted higher levels of patient satisfaction in group S in contrast with the control group. The small sample size and single-center settings limit the research. The research did not assess the impact of the different interventions on functional outcomes, such as range of motion or strength.

5.1. Conclusions

Ultrasound-guided ICBN and SPB provide superior anesthesia and postoperative analgesia as opposed to TICBN following the creation of AVF on the arm's medial side as evidenced by diminished number of patients who needed LA supplementation, prolonged time to 1st rescue analgesia, total fentanyl consumption in the 1st 24 hours and diminished pain scores.