1. Context

An infant’s immune system is shaped by inherited factors (maternal genes/autoantigens), the gut microbiota, and exposure to pathogens. The microbiota’s balance establishes immune homeostasis, fostering tolerance and defense. It interacts with immune cells, supports healthy responses, and is essential for immune development and organ maturation (1). Early life is crucial for forming a healthy gut and oral microbiome that guides immune development and lifelong health. A deficiency of beneficial bacteria, such as Streptococcus, in infancy can cause lasting immune problems and higher disease risk. Therefore, promoting healthy bacterial growth in babies is important (2). A baby's early gut bacteria have a lasting impact on its health. The first microbes to colonize the gut, mainly facultative anaerobes such as Enterobacterales, Enterococci, and Staphylococci, shape the gut's future microbial makeup and influence long-term development (3). Early colonizers occupy intestinal binding sites and resources, blocking newcomers. Mostly facultative anaerobes, they alter the gut by consuming nutrients, producing antimicrobials, and generating metabolites, shaping the community. Over time, the starter microbiota shifts to obligate anaerobes (e.g., Clostridium leptum, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides fragilis) due to their influence. These initial colonizations are crucial for the mature microbiome and may affect future health (4).

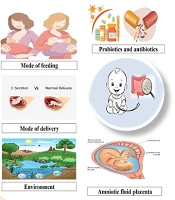

When solid foods are introduced, the gut microbiota mainly includes Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. The initial colonizers are affected by maternal and infant factors. These influences can result in different patterns in the growth of oral and gut microbes (5). Interruptions in initial oral microbial colonization can influence the development of both oral and systemic health issues in children (Figure 1) (6). Research links oral bacteria to weight gain, rheumatoid arthritis, and autism. The mouth is a gateway to the digestive tract, and oral microbes can influence the gut, suggesting oral microbiota may complement or substitute for gut microbiota. The gut microbiome protects against pathogens and strengthens immunity by colonizing mucosal surfaces and producing antimicrobial compounds (7). Immunosuppression or primary immunodeficiencies can disrupt how the microbiome educates the immune system. In healthy development, gut microbes promote the maturation of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), foster regulatory T-cells, stimulate secretory IgA, balance T-helper (Th) 1/Th2/Th17 responses, and reinforce barrier integrity. When immunity is compromised or drugs blunt microbial signals, education can be blunted or mistimed, leading to dysbiosis (lower diversity or pathobiont overgrowth), reduced antimicrobial peptides, and weaker colonization resistance. This can slow or skew immune maturation, raise mucosal inflammation and infection risk, and affect vaccine responses or immune reconstitution after transplant or chemotherapy. The microbiome also influences immunosuppressive therapy efficacy and toxicity, a bidirectional relationship, especially in early life when immune education is plastic (8). This review summarizes how the oral and gut microbiomes develop in the first 1,000 days and interact with the immune system, highlighting maternal health, delivery mode, feeding, antibiotics, host traits, and environment as key determinants of infant microbiota and immune maturation.

2. Evidence Acquisition

We conducted a structured literature search of PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar to identify studies published from 2021 through 2025 that investigate the development of the infant immune system in relation to the microbiome. A comprehensive search strategy and keywords related to early-life microbial communities and immune ontogeny were used, including terms such as “early-life microbiome”, “gut microbiome”, “oral microbiome”, “fecal microbiota”, “intestinal microbiota”, “immunological development”, “immune maturation”, “neonates”, and “infants”, to map cross-concept connections. All searches and study screenings were conducted to maximize sensitivity while maintaining specificity for infant populations and relevant immunologic and microbiome outcomes.

3. Results

3.1. Prenatal Factors

3.1.1. Maternal Microbiota

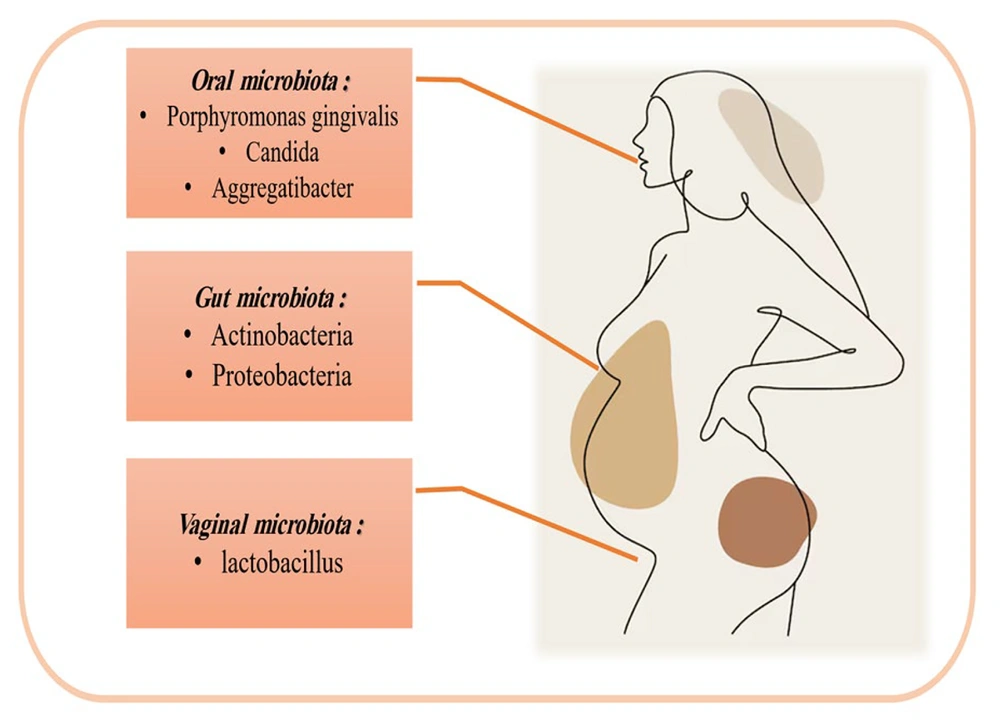

New evidence challenges the view of a sterile womb. Bacteria have been found in meconium, placenta, and amniotic fluid, with Staphylococcus most common in meconium and Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium also present (9). While some findings may reflect contamination, rigorous controls and advanced sequencing (e.g., PacBio SMRT) show fetal feces and amniotic fluid harboring microbial communities above background (10). Placental microbiota analyzed by Aagaard et al. reveal a distinct group dominated by intestinal-associated taxa — Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Fusobacteria — related to the maternal oral microbiome and potentially influencing outcomes (11). The amniotic and placental microbiomes are alike. Imbalances in these microbes may cause chorioamnionitis. Amniotic fluid microbes might predict preterm birth (12). Amniotic and placental microbiomes are similar; imbalances can cause chorioamnionitis, and amniotic bacteria can predict preterm birth. Fetal colonization appears prenatal, sourced from maternal oral, gut, and vaginal microbiota, with maternal health shaping the baby’s microbiome (13). Notably, the composition of the maternal oral, intestinal, and vaginal microbiota undergoes significant changes during pregnancy, which may explain the close relationship between maternal microbiota and that of the fetus and infant (Figure 2). During pregnancy, the maternal microbiome shifts: Oral taxa such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans rise in early to mid-pregnancy; Candida increases mid to late gestation; Actinomyces remains elevated (14). The gut microbiome shows more Actinomycetes and Proteobacteria and fewer butyrate-producing Faecalibacterium, with lower within-person but greater between-person diversity in the third trimester (14). Lower microbial diversity within individuals, but greater differences between individuals, occurs in the third trimester. This suggests chronic inflammation. These gut changes help regulate fetal metabolism. Maternal immune system adaptations are crucial for fetal acceptance, preventing rejection, and fighting infection (15). The vaginal microbiome becomes Lactobacillus-dominated, with lower diversity and load early and a lower pH linked to better outcomes; reduced Lactobacillus associates with preterm labor. Maternal microbiome changes can reach the placenta/fetus via bloodstream or immune-cell routes; endometrial samples harbor gut and vaginal taxa (Bacteroides, Proteus, Lactobacillusiners/crispatus, Prevotella amnii). Microbes crossing the placenta may upregulate MAMP receptors and influence TH1/TH17 pathways (IRF7) (16).

3.1.2. Antenatal Antibiotics

Studies show that antibiotics taken during pregnancy can alter the developing baby's gut bacteria (17). Research comparing infants exposed to prenatal antibiotics with those unexposed found lower levels of beneficial bacteria like Bacteroides and higher levels of potentially harmful bacteria such as Escherichia and Shigella in the antibiotic-exposed group (18). A broader analysis confirmed these findings, showing that antibiotic exposure in the womb is linked to decreased Actinobacteria and increased Firmicutes and Proteobacteria in infants' gut microbiomes (19). Prenatal antibiotics in mice disrupt offspring immunity by reducing butyrate and compromising ILC2, weakening antiviral immunity (20). Maternal antibiotics disrupt the infant gut microbiome, raising obesity, ear infections, and asthma risks, and may hinder immune development by altering gut and oral bacteria.

3.1.3. Prenatal Environmental Exposure

Early exposure to environmental pollutants and bacteria during development can influence the formation of the fetal oral and intestinal microbiota, as well as the immune system. Recent studies suggest that maternal inhalation of Particulate Matter 2.5 microns or less in diameter (PM2.5) can induce oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, hormonal disturbances, and epigenetic changes, potentially negatively affecting normal fetal development. Furthermore, inhaled PM2.5 can breach the alveolar epithelial barrier, enter the bloodstream, and accumulate in the placenta, possibly causing direct damage to its structure and function, which can impair fetal growth. In a research, pregnant mice were subjected to either filtered air (FA) or concentrated ambient PM2.5 (CAP), showing that exposure to CAP altered the metabolome and disrupted metabolic pathways such as amino acid and lipid metabolism in both maternal blood and the placenta (21). Exposure of mothers to air pollutants during the initial and final stages of pregnancy has been associated with alterations in the fetal white blood cell distribution and may lead to an imbalance in fetal Th cell subsets, increasing the likelihood of allergic responses in offspring (22). Loss et al. studied the mRNA levels of Toll-like receptors (TLR) 1 to TLR9 and CD14 in umbilical cord blood, finding that the overall expression of innate immune receptors was typically elevated in the cord blood of infants born in rural regions, especially for TLR7 and TLR8 (23). Additionally, exposure to farm environments during pregnancy can influence the developing immune system of the offspring. Examination of umbilical cord blood from mothers exposed to farms revealed a decreased Th2 immune response, a reduced number of white blood cells, an increase in Treg cells, and improved immunosuppressive functions, along with higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 (24).

3.2. Postnatal Factors

3.2.1. Mode of Delivery

While the mother's body plays a role in initial fetal microbial exposure, a baby's microbiome is primarily established during birth. Vaginal delivery (VD) and cesarean section (CS) result in different microbial communities colonizing the newborn, impacting the development of both oral and gut microbiomes (25). The first week of life for vaginally delivered infants shows their mouths and intestines populated largely by bacteria also found in their mothers' vaginas, including Lactobacillus, Prevotella, and Bifidobacterium (26). Newborns delivered vaginally acquire bacteria from their mothers' vaginas and guts, including Lactobacillus, Prevotella, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroidetes, and Escherichia coli. These bacteria thrive in the infant gut. The VD is associated with higher levels of gram-negative bacteria in the infant, potentially increasing lipopolysaccharide (LPS) production (27). Exposure to LPS from gut microbes in newborns influences their immune response. The LPS stimulates immune cells, increasing markers like TNF-α and IL-18, suggesting a link between gut bacteria and the immune status of infants. This LPS exposure might contribute to developing tolerance to gut microbiota and activating the neonatal immune system, potentially reducing the risk of later immune disorders. Infants born vaginally exhibit heightened immune cell activity in their cord blood, including increased cytokine levels and expression of immune-related receptors (TLR2, TLR4, CD16, CD56), indicating a stronger initial immune response compared to those born via cesarean (28).

Babies born via CS acquire a different gut microbiome than those born vaginally. Their gut bacteria more closely resemble those on their mother's skin, such as Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Propionibacterium, lacking the Bifidobacterium commonly found in vaginally delivered infants. The CS babies also have less bacterial diversity overall and a lower proportion of Bacteroides. Furthermore, they tend to have more potentially harmful bacteria, such as C. perfringens and E. coli. This altered microbiome may be related to lower levels of immune cells, like lymphocytes and dendritic cells, and reduced immune receptor activity in their umbilical cord blood, suggesting a potentially weaker initial immune response (29). The timing of birth via CS may interfere with a key developmental window for the immune system, potentially reducing the positive effects of acquiring the mother's beneficial microbes and the immune system's natural activation during VD (27). Studies in mice indicate that the timing and strength of early immune system activation significantly impact long-term human immune health (30). The CS delivery is associated with a greater risk of childhood immune problems like asthma, allergies, leukemia, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) compared to VD. This difference likely stems from the impact of the delivery method on the infant's gut microbiome and immune system development. CS may expose newborns to more antibiotics and alter breast milk composition, increasing opportunistic pathogens and negatively affecting immune and metabolic development. While research, such as that by Selma-Royo et al., shows differences in early gut microbiota between home and hospital births, persisting for up to six months, the long-term impact of the delivery method appears to lessen over time (31). The impact of birth method on infant gut microbiota and subsequent development isn't solely determined by Cesarean versus VD. Other factors, such as the birth setting (e.g., home versus hospital), also play a significant role and need to be considered for a complete picture of how early colonization influences long-term health.

3.2.2. Feeding Methods

Newborns receive a significant bacterial inoculum through breast milk, which is not sterile as previously thought. This milk contains various bacterial species, such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Bifidobacterium, Propionibacterium, and Lactobacillus (32). The World Health Organization advises starting breastfeeding immediately after birth and continuing exclusively for six months (33). The bacteria in a breastfed baby's mouth closely match those found in the mother's mouth, breast milk, and nipples. Streptococcus typically dominates the oral microbiome of exclusively breastfed infants, unlike formula-fed babies, who often show higher levels of Actinomyces and Prevotella (34). Additionally, infants who are fed formula without probiotics or human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) tend to have lower levels of Bifidobacterium in their gut microbiota compared to breastfed infants, and adding Bifidobacterium to formula does not significantly increase its presence in the gut of infants (35). The differences in initial microbiota caused by varying feeding practices can have lasting impacts on the oral and intestinal microbiota of infants (Table 1) (36).

| Year | Author | Probiotics | Findings | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | Kubota et al. | Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938 | Marked increase in bowel movements in patients with functional constipation | (37) |

| 2021 | Mageswary et al. | Bifidobacteriumlactis Probio-M8 | Improving outcomes for hospitalized children under two with acute RTIs by decreasing symptom duration, antibiotic use, and hospital stays | (38) |

| 2022 | Sowden et al. | L. acidophilus, B. bifidum, and B. infantis | Preventing NEC and feeding problems in premature infants | (39) |

| 2022 | Guo et al. | Oropharyngeal Probiotic ENT-K12 | Reduced acute respiratory infections, symptom duration, medication use, and school/work absences in school-aged children | (40) |

| 2023 | Luoto et al. | L. rhamnosus GG ATCC 53103 | Promoting a Bifidobacteria-rich gut microbiome to reduce microbiota imbalances in preterm infants | (41) |

| 2023 | Li et al. | L. paracasei N1115 | Increased lactic acid bacteria, fecal sIgA, and stable fecal pH | (42) |

| 2023 | Hiraku et al. | B.longum subsp. infantis M-63 | Lower fecal pH, higher levels of acetic acid and IgA, and less frequent, less watery stools contributed to a Bifidobacteria-rich gut microbiome in full-term infants during key developmental stages | (43) |

Abbreviations: RTIs, respiratory tract infections; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; sIgA, secretory immunoglobulin A.

The development and maturation of both the innate and adaptive immune systems in newborns occur over time. Initially, during the first few days, immune-related components like secretory immunoglobulins in breast milk serve as the primary source of antibodies and immune cells (44). Breast milk is rich in secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA), which plays a vital role in clearing pathogens, colonizing microbiota, and maintaining microbiota balance by affecting gene expression within the microbiota (45). Research indicates that maternal sIgA may help shape the oral microbiota by limiting the growth of potentially harmful species, safeguarding mucosal epithelial cells, and preventing the adhesion of specific pathogenic bacteria (46). Studies show that the levels of sIgA in the feces of breastfed infants at around six months are significantly higher compared to those fed formula. Additionally, breast milk contains various immunoglobulins, complement proteins, lysozyme, and lactoferrin — antimicrobial agents that protect infants from infections and support their immune development. In newborn mice, IgG from breast milk can enter the bloodstream through the Fc receptor (FcRn), providing crucial protection against mucosal diseases caused by E. coli (47). The predominant cytokine in human milk is IL-10, which helps suppress immune responses and promotes tolerance to dietary and microbial antigens (48). Breast milk also contains immune cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, which can be transferred directly to the infant, stimulating an immune response and influencing the development of the infant's immune cell types, particularly B and T-cells (49).

Human milk contains various bioactive components, particularly those related to the metabolism of HMOs (50). A study examined the microbiota-dependent effects of HMOs. The HMOs act as infant prebiotics, promoting Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus. They regulate intestinal epithelial cells, strengthen barrier function, and supply substrates that shape the developing microbiota and mucosal immunity. The HMOs also modulate immunity and compete with pathogens, reducing adhesion and invasion. Some gut bacteria ferment HMOs into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that influence immunity and activate GPR41/43, a pathway linked to less allergic asthma and colitis in mice. Thus, higher HMO/SCFA levels from longer breastfeeding may help prevent allergies. Breast milk supports gut/oral microbiomes and immune development; prolonged breastfeeding is linked to better cognition and lower obesity/diabetes risk (51).

3.2.3. Antibiotic Exposure

Early exposure to antibiotics significantly alters the oral and intestinal microbiota. Studies show reduced microbial diversity and changes in bacterial community structure, with some bacteria (like Granulicatella) becoming less prevalent, while others (Prevotella) become more abundant after antibiotic treatment. Specific antibiotic use correlates with increases in certain bacterial families (Pasteurellaceae, Neisseriaceae) and decreases in others (Prevotellaceae) (52). This disruption is linked to an increased abundance of Enterobacteriaceae, antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), and multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) (53). Long-term effects include altered proportions of oral bacteria like Neisseria, Streptococcusmitis/dentisani, Prevotella, and Actinomyces, depending on antibiotic exposure (36). Reduced microbial diversity persists into childhood. Animal studies show that early antibiotic exposure disrupts immune balance, potentially increasing susceptibility to asthma, allergies, IBD, Crohn's disease, type 1 diabetes, and other diseases (54).

3.2.4. Environmental Exposure

Research increasingly indicates that environmental influences, rather than genetics, are the primary drivers of gut microbiome composition. This microbiome, along with environmental biodiversity and the human immune system, forms a complex, interacting network. Air pollutants, ingested through food and drink or inhaled and transported to the gut via the lungs, significantly alter the gut microbiome (55). This alteration manifests as shifts in bacterial populations (e.g., Bacteroides, Firmicutes, and Verrucomicrobia) and increased oxidative stress and inflammation, ultimately disrupting gut health (56). Exposure to farm environments helps shape a baby's gut bacteria in a way that protects against asthma. This demonstrates how the environment a baby is exposed to after birth plays a key role in the development of their gut and mouth bacteria (57).

4. Conclusions

The first 1000 days shape oral-gut microbiomes; the oral-gut axis links oral health to disease. Dysbiosis stems from antibiotic overuse, maternal health, and environment, with rising resistance. Probiotics guide microbiome development and immune maturation, reducing allergies, asthma, and infections; Bifidobacterium breve M-16V and B. longum BB536 show eczema benefits. FMT/microbial ecosystem transplantation (MET) could correct dysbiosis after cesarean birth, but safety formulations require evaluation. Future work: Personalized nutrition and maternal factors to craft pediatric therapies.