1. Background

Hepatitis E is caused by the hepatitis E virus (HEV), an increasingly serious global public health problem, which can be transmitted through contaminated food or water (1), blood transfusions, organ transplants, placentas, etc. (2). The results of a previous study showed that the number of hepatitis E cases has been on the rise from 1990 to 2019, with a 19% increase since 1990 (3). According to WHO data, around 20 million people globally contract the HEV each year, leading to about 3.4 million acute cases and 70,000 hepatitis E-related fatalities (4). The incidence of hepatitis E in low-income countries (such as East Asia, South Asia, and Africa) is relatively higher than that in high-income countries (5). Meanwhile, pregnant women are the main high-risk group for hepatitis E, with up to a 30% mortality rate (6). Hepatitis E has imposed a significant economic burden on the Chinese people. Data from the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention showed that the proportion of hepatitis E was one in a thousand among all infectious diseases (7). A health economics study conducted in Jiangsu province showed that the economic burden caused by hepatitis E cases accounted for 60.77% of the per capita disposable income (8).

At the end of 2019, COVID-19 broke out in Wuhan, China, and was regarded as a public health emergency in January 2020. COVID-19 causes serious damage to the human body and disrupted health services in 90% of countries around the world due to the reassignment of healthcare personnel and supplies and some other policy measures (9). A prior study showed that home quarantine and mistrustfulness related to COVID-19 anxiety seriously affected people's mental health (10). At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the responsiveness of the healthcare system (11). Similarly, the screening and treatment of hepatitis E also faced significant challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, healthcare for other clinical conditions was disrupted, and the incidence of various infectious diseases such as hepatitis B, tuberculosis, and dengue fever decreased (12, 13). A study from Spain showed that hospitalizations for viral hepatitis in Spain decreased by 18% during the COVID-19 pandemic (14). The COVID-19 pandemic also reduced the dispensing of antivirals (such as HIV and HCV) through retail pharmacies, mail order, and long-term care pharmacies (15). However, there are few studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis E, and the causal impact of COVID-19 on hepatitis E incidence is unclear.

The autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model is a common time series analysis and prediction model, which has been widely applied in fields such as economics and currently plays an important role in medical research. The Bayesian structured time series (BSTS) model is effectively used to estimate dynamic systems. Compared with classical time series models, the recently introduced BSTS model has some attractive advantages and is used to study intervention analysis of dynamic time series.

2. Objectives

Considering the changes in the epidemiology of hepatitis E in China, this study attempts to use intervention analysis under the BSTS model to explore the impact of COVID-19 on hepatitis E and predict its epidemic trend using ARIMA and BSTS models.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

Data on the incidence of hepatitis E in China from January 2012 to July 2022 were obtained from the China Center for Disease Prevention and Control. Hepatitis E is a reportable infectious disease in China. All confirmed hepatitis E cases must be reported through the National Notifiable Infectious Diseases Reporting Information System offered by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. We employed ARIMA and BSTS models to analyze the hepatitis E data from January 2012 to July 2021 as the training set and validated the prediction accuracy using data from August 2021 to July 2022 as the testing set.

3.2. Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average Model

When the data exhibits periodic and seasonal trends, the ARIMA model can be expressed as seasonal ARIMA (p, d, q) (P, D, Q)s, where p, d, q represent the order of the non-seasonal autoregressive model (AR), differencing, and moving average model (MA), while P, D, Q, s represent the seasonal AR order, differencing, MA order, and cycle. The parameter estimation of the ARIMA model involves four processes (16).

3.2.1. Data Stationarity Test

The ARIMA model requires the time series data to be stationary, which can be tested using the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test. If the time series data (P-value of the ADF > 0.05) is non-stationary, non-seasonal and seasonal differencing are required to transform the data into a stationary state, which determines the values of d and D.

3.2.2. Parameter Estimation

The values of p, q, P, and Q can be roughly determined by examining the autocorrelation function (ACF) plot and partial autocorrelation function (PACF) plot. Then, the parameters for each of the candidate models are estimated, and the model with the minimum value of the Akaike information criterion (AIC) or Bayesian information criterion (BIC) is selected as the optimal model.

3.2.3. Model Diagnosis

The adequacy of the fitted optimal model is checked using a white noise test (such as ACF and PACF plots of residual sequences, or the Ljung-Box Q test), aiming to confirm that the residual sequence of the model is a white noise sequence. Once the fitted optimal model passes the white noise test, it indicates that the model is adequate for data fitting.

3.2.4. Model Prediction

The identified optimal model is used to predict the future trend of hepatitis E.

3.3. Bayesian Structured Time Series Model

In this study, a counterfactual framework was used to construct the BSTS model, and the incidence trend of hepatitis E was forecasted by comparing the monthly counterfactual cases with observed cases. The BSTS model consists of the Kalman filter, spike and slab regression, and Bayesian model averaging. The monthly hepatitis E cases were fitted in the BSTS model by the local linear trend, seasonal variations, and regression components. The Kalman filter was used to predict the time series, and the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) was used to simulate the posterior distribution to obtain the final prediction result. The Bayesian model averaging method is employed to smooth a large number of potential models (17).

Intervention analysis under the BSTS model is used to estimate the causal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis E incidence. Data before the occurrence of COVID-19 is used as the pre-processing period to predict the value of hepatitis E in China without the intervention measures during the COVID-19 pandemic (counterfactual). In the period after the occurrence of COVID-19, the difference between the predictive sequence and the real sequence was calculated and used to estimate the impact of COVID-19 on hepatitis E in China. Contrary to traditional linear models, these models measure the impact of evolution based on the dynamic confidence interval of the difference between intrinsic and counterfactual observations.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The long-term trends and periodicities of the data on hepatitis E incidence were decomposed by the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter. The Seasonal Index method was used to obtain the Seasonal Index of the time series data. The 'forecast' package and 'BSTS' package were used to create the ARIMA model and BSTS model in R4.20 software. The causal impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis E have been analyzed using the 'CausalImpact' package under the BSTS model. The prediction accuracy of the two methods was judged by calculating the mean absolute error (MAD), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), root mean square error (RMSE), and root mean square percentage error (RMSPE). These measures can effectively determine the validity and prediction accuracy of the models. The smaller the error indicators, the higher the predictive performance of the model.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

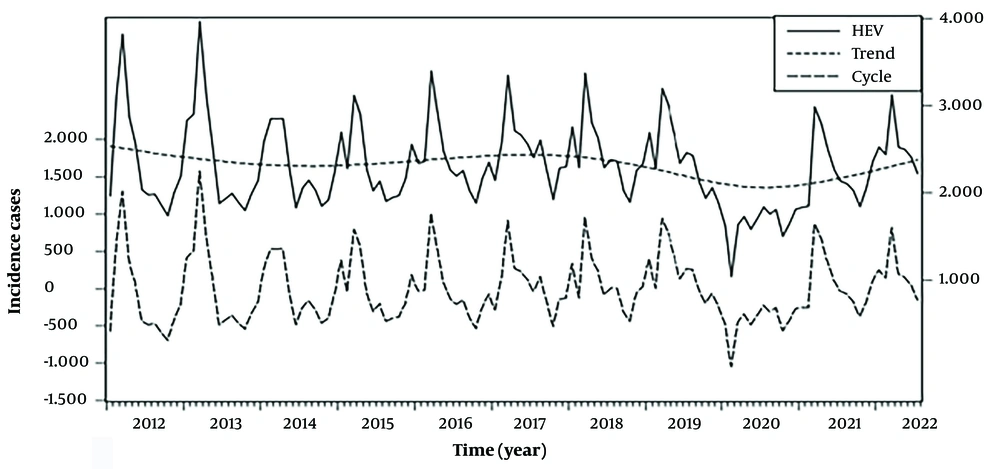

From January 2012 to July 2022, the total hepatitis E cases in China were 294,006, and the average monthly cases were 2,315 (the average monthly incidence rate was 0.017 per 100,000 people). The results of the cycle and trend pattern of the hepatitis E incidence sequence showed a certain cyclical pattern (Figure 1). The seasonal indices from January to December were 1.02, 1.02, 1.37, 1.19, 1.05, 0.93, 0.96, 0.93, 0.88, 0.79, 0.89, and 0.95, respectively, indicating that the incidence of hepatitis E in China showed seasonal fluctuations, with the highest incidence in March each year.

Hepatitis E incidence sequence and trend pattern based on Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter decomposition in China from January 2012 to July 2022; the solid line represents the reported hepatitis E cases. The thin dotted line represents the trend of hepatitis E cases. The long dashed line represents the cycle of hepatitis E cases.

4.2. Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Decrease in Hepatitis E Case Notifications

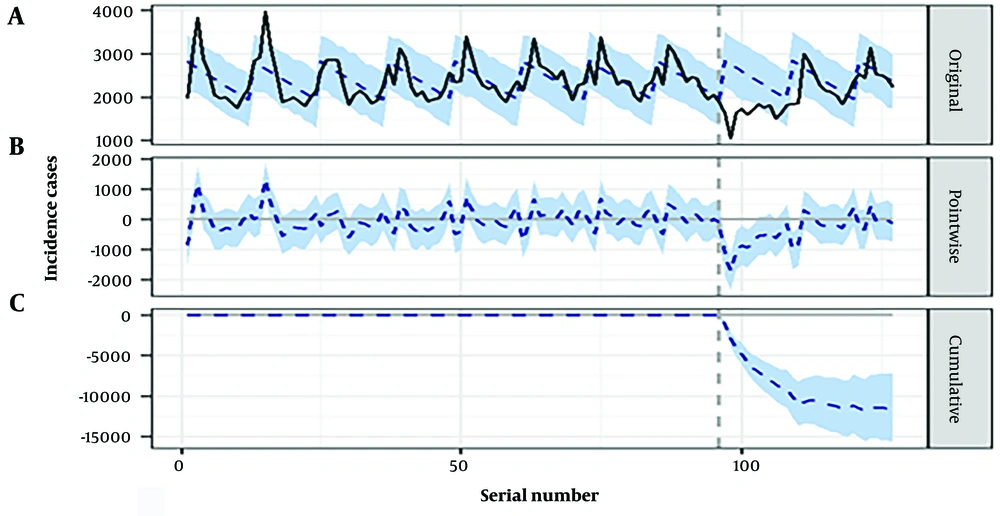

The monthly average hepatitis E cases decreased by 41% (95% CI: -51% ~ -31%) from January to June 2020 (probability of causal effect: 99.89%, P = 0.001) and by 32% (95% CI: -40% ~ -23%) from January to December 2020 as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic (probability of causal effect: 99.89%, P = 0.001; Appendix 1 in Supplementary File). The hepatitis E incidence showed a downward trend during 2020, and the posterior probabilities (as random events) that lead to these effects can be rejected, while the probabilities of the causal effects can be accepted (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File). There was a decrease of 19% (95% CI: -26% ~ -13%) from January 2020 to December 2021 and a decrease of 15% (95% CI: -21% ~ -9.4%) from January 2020 to July 2022 (Figure 2), indicating the reduction impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis E incidence from 2020 to 2022.

Time series plot displaying the causal impacts of COVID-19 on hepatitis E incidence from January 2020 - July 2022: A, the reported hepatitis E cases (solid line) and the number of hepatitis E estimated by the model (dashed line); B, the difference between reported cases and the number of hepatitis E estimated by the model; C, cumulative effect of COVID-19 on hepatitis E incidence.

4.3. Parameter Selection for Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average and Bayesian Structured Time Series Models

4.3.1. Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average Model

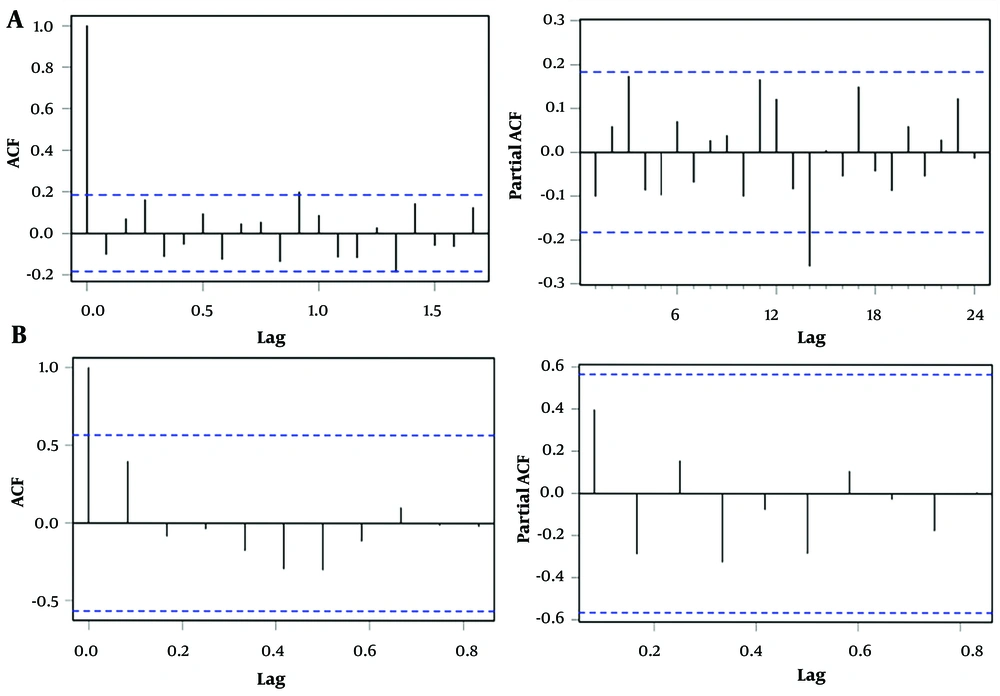

We fitted the incidence of hepatitis E in China from January 2012 to July 2021 based on the ARIMA modeling process. After seasonal and non-seasonal differences, stationary data were obtained (P-value of ADF < 0.01). Through simulation, the ARIMA (1,0,0) (0,1,1) 12 structure with the smallest values of AIC (1454.03) and BIC (1461.93) among all candidate models was selected as the optimal model. Further tests of the model coefficients showed: AR1 = 0.72 (t = 10.33, P < 0.001), SMA1 = -0.62 (t = -5.98, P < 0.001). The ACF and PACF plots of the residuals showed that the different lag correlation coefficients were basically within the 95% CI (Figure 3A); Ljung-Box Q test results (χ2 = 78.01, P = 0.59) indicated that the model residual sequence was white noise. Therefore, the ARIMA (1,0,0) (0,1,1) 12 structure can fully fit the incidence trend of hepatitis E.

4.3.2. Bayesian Structured Time Series Model

During the fitting of the BSTS model, we found that a BSTS model with added local linear trend and seasonal state components was best suited to predict our data. To ensure the convergence of Bayesian inference, 1,000 MCMC iterations were performed. The model diagnosis results showed that the correlation coefficients in the residual ACF and PACF plots fell within the 95% CI (Figure 3B); Ljung-Box Q test results (χ2 = 2.51, P = 0.28) indicated that the model residual sequence was white noise. The diagnostic results indicated that using the BSTS model to simulate hepatitis E data was sufficient and appropriate.

4.3.3. Prediction and Accuracy of Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average and Bayesian Structured Time Series Models

The prediction results of the optimal ARIMA and BSTS methods for the incidence of hepatitis E from August 2021 to July 2022 are listed in Table 1. Generally, the smaller the error indicators, the higher the prediction performance of the model. The forecasting accuracy results showed that the error indicators of MAD (214.42 vs. 274.25), MAPE (8.30 vs. 11.30), RMSE (189.98 vs. 318.86), and RMSPE (0.38 vs. 0.45) under the BSTS model were smaller than those under the ARIMA model, indicating the predicting accuracy of the BSTS model was higher. Then, the BSTS model was reconstructed using data from January 2012 to July 2022 and used to predict the number of hepatitis E cases in China from August 2022 to December 2023 (Table 2). The total number of new cases in the next 17 months would be 37,704, and the epidemic trend of hepatitis E would remain stable.

| Time | Observed Values | ARIMA | BSTS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forecast | 95%CI | Forecast | 95%CI | ||

| 2021-08 | 2109 | 1935 | 1320 - 2460 | 2121 | 1597 - 2645 |

| 2021-09 | 2033 | 1752 | 1020 - 2669 | 1972 | 1327 - 2617 |

| 2021-10 | 1846 | 1991 | 932 - 3043 | 1750 | 1050 - 2450 |

| 2021-11 | 2055 | 2083 | 1249 - 3176 | 1947 | 1221 - 2673 |

| 2021-12 | 2369 | 2269 | 858 - 3552 | 2024 | 1284 - 2763 |

| 2022-01 | 2530 | 2199 | 761 - 3454 | 2071 | 1325 - 2817 |

| 2022-02 | 2443 | 3024 | 1545 - 4583 | 1865 | 1115 - 2615 |

| 2022-03 | 3131 | 2675 | 1209 - 4404 | 2789 | 2038 - 3541 |

| 2022-04 | 2525 | 2286 | 613 - 4188 | 2583 | 1831 - 3336 |

| 2022-05 | 2503 | 2012 | 294 - 4033 | 2325 | 1573 - 3078 |

| 2022-06 | 2411 | 2083 | 321 - 4151 | 2147 | 1394 - 2900 |

| 2022-07 | 2225 | 2085 | 334 - 4268 | 2150 | 1397 - 2903 |

Abbreviations: ARIMA, autoregressive integrated moving average; BSTS, Bayesian structured time series.

| Time | Forecast | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|

| 2022-08 | 2198 | 1699 - 2698 |

| 2022-09 | 2046 | 1429 - 2662 |

| 2022-10 | 1852 | 1183 - 2522 |

| 2022-11 | 2059 | 1364 - 2755 |

| 2022-12 | 2242 | 1534 - 2951 |

| 2023-01 | 2373 | 1658 - 3088 |

| 2023-02 | 2254 | 1536 - 2973 |

| 2023-03 | 3026 | 2306 - 3747 |

| 2023-04 | 2590 | 1869 - 3312 |

| 2023-05 | 2413 | 1691 - 3135 |

| 2023-06 | 2248 | 1525 - 2970 |

| 2023-07 | 2187 | 1465 - 2909 |

| 2023-08 | 2168 | 1412 - 2925 |

| 2023-09 | 2016 | 1242 - 2790 |

| 2023-10 | 1820 | 1037 - 2604 |

| 2023-11 | 2028 | 1240 - 2816 |

| 2023-12 | 2184 | 1394 - 2974 |

5. Discussion

In this study, the Seasonal Index results showed that hepatitis E incidence had seasonal fluctuations. This result is consistent with previous research findings (5). The reason for this may be that people visit relatives and friends during the Spring Festival in China, which increases the opportunities to come into contact with food contaminated with the HEV. Therefore, people should monitor their food and exercise prudence during the Spring Festival. Although some impacts have been mitigated through policy measures, the COVID-19 pandemic may have medium and long-term effects on the disease pattern.

In this study, we employed the intervention analysis method under the BSTS model to explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the hepatitis E epidemic in China. The monthly average hepatitis E cases decreased by 41% from January to June 2020 (probability of causal effect: 99.89%, P = 0.001) and by 32% from January to December 2020 as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic (probability of causal effect: 99.89%, P = 0.001), indicating that the decrease in hepatitis E incidence was causally related to the COVID-19 pandemic. This decline translates to approximately 760 fewer cases monthly from January to December 2020, reducing the healthcare burden. From 2021 to 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic still reduced the incidence of hepatitis E (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File and Figure 2), which is consistent with previous research conducted in China, which found that hepatitis B incidence (18) and gonorrhea (19) significantly declined during COVID-19. In this study, the reduction in hepatitis E (15%) was higher than that observed in previous studies for gonorrhea and hepatitis B (12%) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The reasons for these results may be that their transmission routes are different. Hepatitis E is mainly transmitted through the fecal-oral route. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, implementing strict home quarantine policies, reducing unnecessary travel, and paying more attention to personal hygiene all contribute to cutting off the fecal-oral transmission route of hepatitis E. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges to healthcare, such as medical staffing, resources, and space, etc. A study showed that a substantial proportion of isolation rooms do not meet the standard conditions, which can pose significant risks during the COVID-19 pandemic (20). As a result, unusual nosocomial infections of hepatitis E have occurred (21). The COVID-19 pandemic might make the hepatitis E control strategy less effective.

Although the ARIMA model may accommodate a variety of time series data sources, its fundamental drawback is the model's presumed linearity (22), leading to sufficient outcomes. At the same time, the ARIMA model relies on large-scale uninterrupted data; therefore, its accuracy may not be ideal when there are some outliers or data loss (23). However, the ARIMA model still holds significant value in predicting the epidemic trend of infectious diseases. In this study, based on the incidence data of hepatitis E in China, the optimal ARIMA (1,0,0) (0,1,1) 12 model was identified, which passed all diagnoses and can effectively predict the trend of hepatitis E in China. An ARIMA (0,0,0) (0,1,0) 12 was selected by Qin et al. (24), based on the incidence data of hepatitis E from 2013 to 2019 in China, which was different from our selected ARIMA model. This difference mainly stems from the changes in factors related to disease infection in different periods (such as environmental and hygiene conditions). This indicates that it is necessary to conduct horizontal or vertical comparisons of models constructed in different regions or at different times.

Given the limitations of ARIMA, we constructed the BSTS model and compared the accuracy of ARIMA and BSTS models in predicting hepatitis E in this study. According to Ke et al. (25), it is generally believed that the model performs highly accurate forecasts (MAPE value ≤ 10%), good forecasts (10% < MAPE ≤ 20%), reasonable forecasts (20% < MAPE < 50%), and inaccurate forecasting (MAPE > 50%). Our research results showed that the MAPE value under the BSTS model was 8.30, lower than the MAPE value (11.30) under the ARIMA (1,0,0) (0,1,1) 12 model, indicating the BSTS model had higher prediction accuracy than the ARIMA model. Moreover, the error indicators of MAD, MAPE, RMSE, and RMSPE under the BSTS model were smaller than those under the ARIMA model (Table 2), meaning that prediction results using the BSTS model were closer to the observed values, and the prediction results are robust. The results of this research were consistent with those of Feroze et al. (26). The higher accuracy prediction of the BSTS model may be attributed to its numerous advantages, such as its ability to handle various potential covariates and automatically select the most informative predictors. Meanwhile, the BSTS model is capable of effectively showing the stochastic behavior of the target sequence and producing a forecast based on the Bayesian model averaging of the preferred models. Moreover, it can be extended to the dynamic regression framework, allowing the regression coefficients to change dynamically over time (27). These characteristics overcome the limitations of ARIMA, which is why BSTS outperforms ARIMA in predicting hepatitis E in China in this study. Finally, the established BSTS model can be used to predict the future epidemic trend of hepatitis E in China and thereby formulate prevention and control measures.

5.1. Conclusions

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall incidence rate of hepatitis E in China decreased as a result of COVID-19. The BSTS model has strong application value to forecast the hepatitis E trend in China.