1. Background

A significant group of environmental contaminants that may pose risks to human or ecological health are emerging pollutants, which include pharmaceuticals, personal care products (PPCPs), and endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) (1-3). Sources of pharmaceutical chemicals entering the aquatic environment include pharmaceutical industrial waste, human and animal excrement, and hospital wastewater. In wastewater, groundwater, surface water, and drinking water, various pharmaceuticals including antibiotics have been detected at concentrations ranging from mg/L to ng/L (3-8). Tetracycline (TC) antibiotics are broad-spectrum antibiotics widely used in pharmaceuticals. They are primarily used to treat human illnesses but are also added to animal feed to prevent disease and promote growth (9, 10). TC consumption is estimated to reach 5,500 tons annually in the USA and Europe, with up to 90% of ingested TC excreted in urine (11, 12). Reported concentrations of TC in surface and groundwater reached 0.15 μg/L (13, 14). Therefore, the presence of TC in the environment may contribute to the development of bacterial antibiotic resistance and threaten ecological stability and human health (15, 16).

Various techniques have been applied to remove TC from aquatic environments, including activated carbon, membrane filtration, adsorption, and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) (17, 18). AOPs are oxidation technologies used to degrade both organic and inorganic pollutants in water, relying on the generation of highly reactive radicals such as hydroxyl radicals (OH•) (19, 20). The AOPs are classified into two main groups: (1) Photochemical AOPs and (2) non-photochemical AOPs (21, 22). Examples of AOPs applied for antibiotic removal include UV/O₃, UV/VUV, and UV/H₂O₂ processes (23-25).

In the VUV process, vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) radiation is emitted at wavelengths of 185 nm (~10%) and 254 nm (~90%) (2). One advantage of the VUV technique is that it does not require additional chemical oxidants (26). In crude water, only 48% of the 254 nm radiation is absorbed, compared to 99% of the 185 nm radiation (27). Key reactions in the VUV/water process include the photochemical ionization using Equation 1 and homolysis of water using Equation 2, which generate reactive radicals responsible for contaminant degradation (28).

In the VUV/water process, the addition of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) as a strong oxidant not only generates highly oxidizing hydroxyl radicals (HO•) through the photolysis of water at 185 nm, but also produces HO• via the photolysis of H₂O₂ induced by VUV radiation at 185 and 254 nm, using Equations 3 and 4 (2, 27).

In the VUV/H₂O₂ process, the photolysis of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) by 185 and 254 nm radiation generates additional hydroxyl radicals (HO•), which accelerates the degradation of pollutants (2, 27). Recently, significant attention has been paid to the use of vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) irradiation for the removal of various organic pollutants from water. This process produces HO• radicals through the photoionization of H₂O₂ and water (H₂O), as well as the homolysis of water molecules (Reactions 1 and 2) (2, 27, 28). The addition of H₂O₂ as a strong oxidant enhances HO• generation, thereby increasing the degradation rate of contaminants (29).

This study investigated the degradation of TC using the VUV/H₂O₂ process with a 6 W low-pressure UV lamp (OSRAM Co.). The objective was to evaluate the efficiency of VUV radiation and the VUV/H₂O₂ process for TC degradation and mineralization under various conditions, including solution pH, reaction kinetics, presence of anions, H₂O₂ concentration, and initial TC concentration. Additionally, the effects of several organic compounds such as phenol, oxalic acid, humic acid, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as well as other water contaminants on TC degradation were examined over different reaction times, and the formation of intermediate by-products was identified.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

The following analytical-grade chemicals were acquired from Merck Co.: 30% hydrogen peroxide, sulfate, phosphate, TC, chloride, phenol, oxalic acid, humic acid, para-chlorobenzoic acid, sulfuric acid, and sodium hydroxide.

2.2. Experimental Setup and Procedure

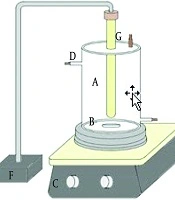

A batch-type cylindrical quartz glass reactor was used for all experiments (Figure 1). The reactor had a working volume of 200 mL, a height of 290 mm, an inner diameter of 50 mm, and an outer quartz tube diameter of 40 mm. The inner walls of the reactor were wrapped with aluminum foil to prevent external UV penetration. A 6-W low-pressure VUV lamp (OSRAM, Germany) was placed at the center of the reactor. The lamp emitted radiation at two wavelengths: 254 nm (approximately 90% of total output; intensity: 56 μW cm⁻² at 1 cm) and 185 nm (approximately 10% of output; intensity: 5 μW cm⁻² at 1 cm). During operation, the solution was continuously mixed using a magnetic stirrer at 100 rpm.

The effects of various operating parameters were investigated, including pH (5, 7, 9), TC concentrations (5, 10, 20 mg/L), and hydrogen peroxide concentrations (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10 mg/L). Radical scavenging experiments were conducted using phosphate ions, EDTA (1 mM) as a hole (h⁺) scavenger and chelating agent, benzoquinone (BQ; 3 mM) as a superoxide radical (•O₂⁻) scavenger, and tert-butyl alcohol (TBA; 10 mM) as a hydroxyl radical (HO•) scavenger. A mixture of anions present in tap water was also tested. Para-chlorobenzoic acid (pCBA) was used as a chemical probe to quantify hydroxyl radical (HO•) concentration. For HO• measurements, 200 mL of pCBA solution containing 2 mg/L H₂O₂ was irradiated, and 0.5 mL samples were withdrawn every 3 minutes for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. The HO• concentration was calculated using Equation 5 (30).

[HO•] = is all concentration of hydroxide radical

pCBAₜ = pCBA concentration (mg/L) at the time t of the reaction.

pCBA₀ = pCBA concentration (mg/L) at the beginning of the reaction.

KHO•t = Constant reaction of hydroxyl radical with parachlorobenzoic acid

(kHO•, pCBA = 5.0 × 109 M⁻¹ s⁻¹).

2.3. Analytical Methods

Because TC degradation may produce various intermediate compounds that can interfere with UV–Vis spectrophotometric measurements, HPLC was used to ensure accurate and selective quantification of TC. All samples collected from the reactor were immediately filtered and analyzed using an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC system equipped with a UV/Vis diode array detector and a ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm, 3.5 μm). For TC degradation experiments, 1 mL aliquots were withdrawn at predetermined time intervals (every 5 - 10 minutes), filtered through 0.22 μm syringe filters, and injected directly without storage. TC was quantified at 359 nm using an isocratic mobile phase composed of 75% 0.01 mol L⁻¹ oxalic acid and 25% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min⁻¹, with an injection volume of 20 μL. The degradation of pCBA was monitored using the same HPLC system with UV detection at 240 nm. An isocratic mobile phase consisting of 50% acetonitrile (containing 0.5% formic acid) and 50% ultrapure water (containing 0.5% formic acid) was used at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min⁻¹ and an injection volume of 100 μL. Calibration curves for TC and pCBA were prepared using standard stock solutions and serial dilutions covering the analytical concentration range. Both analytes showed excellent linearity (R² ≥ 0.999). All samples were filtered before analysis to prevent column blockage and ensure high reproducibility. The solution pH was adjusted using diluted H₂SO₄ or NaOH and measured with a Philips PW 9422 pH meter.

Chemical oxygen demand (COD) was determined as an indicator of the oxygen required to oxidize organic matter to CO₂ and H₂O under acidic conditions using strong chemical oxidants. Measurements were performed using COD low-range vials and a spectrophotometer at 430 nm. Total organic carbon (TOC) represents the amount of carbon present in an organic compound and is used as an indirect indicator of water quality. TOC analysis was performed before and after treatment under optimal operating conditions to evaluate the mineralization of TC. Samples were collected at 0, 5, 30, and 90 minutes, and the degradation and mineralization efficiencies were calculated using Equations 6 and 7 TOC measurements were conducted using an ACQURAY TOC analyzer (Elementar, Germany) following the hightemperature combustion method (31, 32). Residual hydrogen peroxide was measured spectrophotometrically at 410 nm using titanium (IV) oxysulfate according to DIN 38402 H15. All experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3).

Ci: Initial tetracycline concentration (mg/L)

Ce: Final concentration of tetracycline (mg/L)

TOCi: Initial TOC concentration (mg/L)

TOCe: Final concentration of TOC (mg/L)

4. Results and Discussions

3.1. Effect of pH

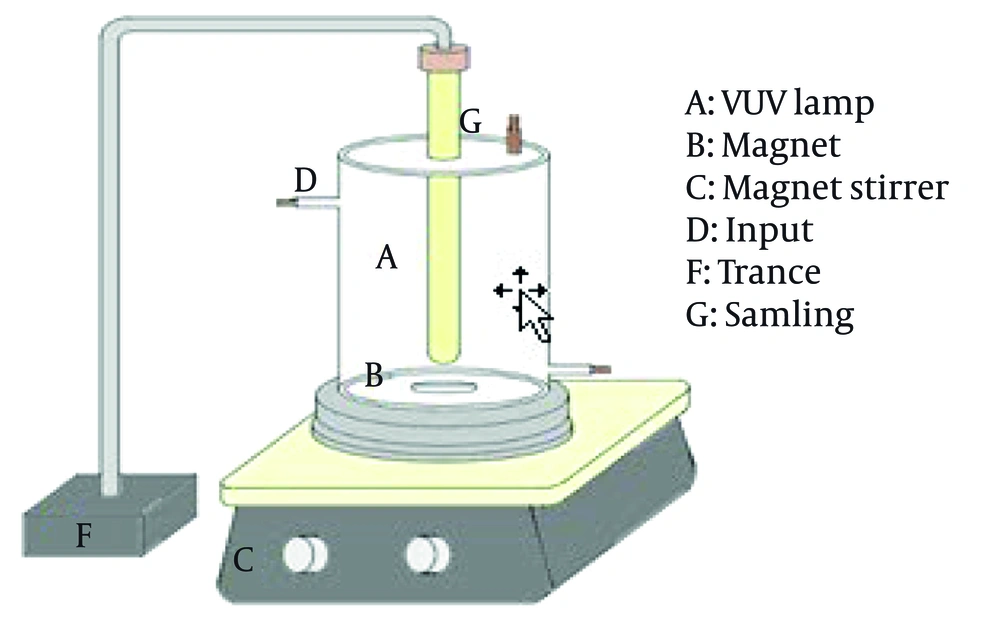

The effect of pH on the removal efficiency of TC (10 mg/L) was evaluated in VUV/H₂O₂ processes, with H₂O₂ at 10 mg/L and a reaction time of 90 min (Figure 2). The removal efficiencies in the VUV/H₂O₂ process were 88.6%, 91.3%, and 93.2% at pH 5, 7, and 9, respectively. Standard deviations were below 3%.

The decrease in removal efficiency under alkaline conditions is mainly due to the formation of hydroperoxide anions (HO₂⁻) from H₂O₂ decomposition, which react with residual H₂O₂ and OH• radicals, thereby reducing the availability of OH•, using Equations 8 - 10 (2, 33). Additionally, at high pH, H₂O₂ photodecomposes to water and oxygen rather than producing OH• radicals, using Equation 11 (34, 35):

TC is an amphoteric molecule, and its speciation depends on pH: It is predominantly positively charged at acidic pH (~4) and negatively charged at alkaline pH (~9). At neutral pH (pH 7), TC exists mainly in a zwitterionic form, which provides a balance between its interaction with OH• radicals and solubility, resulting in optimal degradation (36-38). This explanation aligns with previous studies, such as Elmolla and Chaudhuri, who reported increased degradation of amoxicillin (AMX) at neutral to slightly alkaline pH using UV/TiO₂ and UV/H₂O₂/TiO₂ processes (39). Therefore, pH 7 was selected as the optimal condition because it provides a favorable balance between TC speciation and OH• availability, ensuring efficient degradation without significant radical scavenging or photodecomposition losses.

3.2. Effect of H₂O₂ Concentration

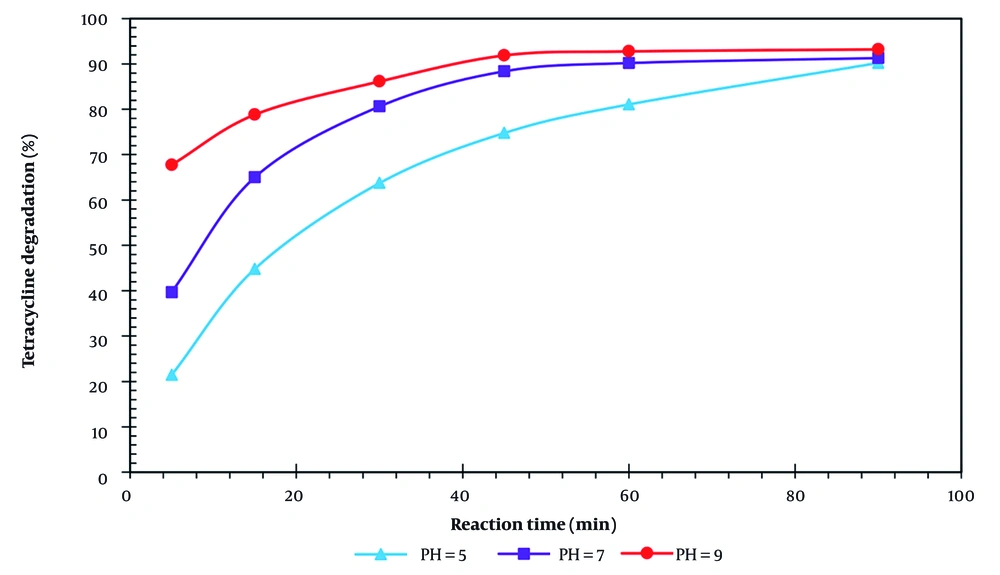

Impact of concentration of H₂O₂ 10 mg/L TC degradation was studied at pH = 7 and for a reaction duration of 90 minutes. According to Figure 3, in order to assess the effects of different hydrogen peroxide concentrations (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 10 mg/L), the synergistic effect of VUV/H₂O₂, and the optimal hydrogen peroxide concentration. The TC removal rate in the VUV/H₂O₂ process, using only different concentrations of H₂O₂ (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 10 mg/L), was found to be (2.48, 4.76, 5.95, 6.09, and 6.64%), respectively, and to be (83.54, 100, 93.48, 92.4, 91.35, and 90.55%).

Using Equations 1 and 2 according to the hydroxyl radicals produced during water photolysis and water molecules photoionization, TC removal rate of 60% during the photolysis process (in the absence of H₂O₂) can be attributed (33, 40). Because there were more hydroxyl radicals produced, the removal effectiveness of TC in the VUV/H₂O₂ process increased from 60% to 100% as the hydrogen peroxide concentration, using Equations 3, 4, and 12, increased from 0 to 2 mg/L. When the concentration of H₂O₂ was increased from 3 to 10 mg/L, the efficiency of TC removal in the VUV/H₂O₂ process reduced from 100% to 90.55%. This results in the creation of water and the scavenger HO₂•, which are weaker than hydroxyl radicals, as well as an overreaction of hydrogen peroxide with hydroxyl radicals, using Equations 13, 14, and 15. The recombination of increased HO•% to create H₂O₂, using Equations 15 and 2 is another factor contributing to the loss in TC removal efficiency in the VUV/H₂O₂ process with an increase in H₂O₂ concentration from 3 to 10 mg/L. Another explanation for the decrease in TC removal effectiveness in the VUV/H₂O₂ process when the concentration of H₂O₂ is increased from 3 to 10 mg/L is the high dose of hydroxyl radicals combining to generate H₂O₂, using Equation 15.

Equation 13.

The synergistic effect of adding H₂O₂ to the VUV process, from Equation 16 is used:

At 120 minutes into the VUV process (photolysis), the TC removal rate was 60%; however, when H₂O₂ = 2 mg/L is added to the VUV process (VUV/H₂O₂), the TC degradation rate is 4.76 and 100%, respectively. Thus, a 35.44% synergistic impact of VUV/H₂O₂ was obtained according to Equation 16. As a result, the ideal surface was determined to be 2 mg/L of hydrogen peroxide concentration. Peng et al. looked into the ibuprofen degradation process using UV/H₂O₂. They discovered that when H₂O₂ concentration increased, ibuprofen degradation increased from 0.1 to 0.6 mM. In their investigation, 0.54 mM hydrogen peroxide concentration was found to be the optimal surface, and it was chosen (41). In the VUV/H₂O₂ process, it took 315, 120, 140, 165, 180, and 210 minutes, respectively, to reach the removal efficiency of 100% TC at various hydrogen peroxide concentrations (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 10 mg/L).

3.3. Kinetics of VUV/H₂O₂ and VUV Processes

Kinetics plays an essential role in evaluating the rate of pollutant degradation over time, as it provides valuable insight into the oxidation mechanisms, reaction pathways, and process optimization. In this study, the kinetic behavior of degradation by the VUV/H₂O₂ and VUV processes was investigated at different reaction times (5, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min) under the following conditions: Initial TC concentration of 10 mg/L, pH 7, and 2 mg/L of H₂O₂. To analyze the degradation behavior, zero-order, pseudo-first-order, and pseudo-second-order kinetic models were applied. The corresponding kinetic equations are summarized in Table 1 (42), where C₀ denotes the initial TC concentration, C₀ is the concentration at time t, k is the rate constant, and t represents the reaction time. The goodness of fit between experimental data and the kinetic models was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R²). According to the results, TC removal by both VUV/H₂O₂ and VUV processes followed a pseudo-first-order kinetic model, as evidenced by the higher R² values (0.9942–0.9948) compared with the other models (Table 2). In pseudo-first-order reactions, the reaction rate depends solely on the concentration of one reactant, which is consistent with the linear relationship observed between ln(C/C₀) and reaction time. Similar findings were reported by Hoang et al., who studied dye degradation using UV/persulfate and demonstrated that the removal kinetics in UV-based AOPs also follow a pseudo-first-order model (43).

| Kinetic Models | Values |

|---|---|

| Zero-order | C0-Ct = k.t |

| First-order | Ln(C0/Ct) = -k.t |

| Second-order | 1/Ct - 1/C0 = k.t |

| Processes | Zero-Order | Pseudo-First-Order | Pseudo-Second-Order | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K0 | R2 | K1 | R2 | K2 | R2 | |

| VUV/H2O2 | 0.0083 | 0.9345 | 0.0253 | 0.9942 | 0.0885 | 0.9578 |

| VUV | 0.0062 | 0.9892 | 0.0098 | 0.9948 | 0.016 | 0.9849 |

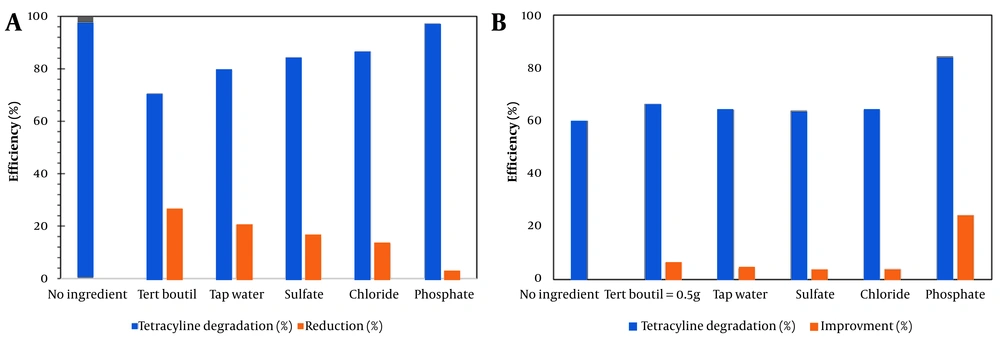

3.4. Effect of Anions on Degradation of Tetracycline in VUV/H₂O₂ and VUV Process

The effects of various anions, including phosphate, sulfate, chloride, tert-butanol, and municipal water, each at a concentration of 1 mM in 200 mL of TC solution, on the reduction of TC removal efficiency under the optimized operating conditions (time = 90 min, H₂O₂ = 2 mg/L, pH = 7, TC = 10 mg/L, wavelength = 359 nm) were investigated in both the VUV and VUV/H₂O₂ processes (Figure 4A and 4B). As shown in Figure 4A, the removal efficiency of TC in the VUV photolysis process was approximately 60% in the absence of anions. However, the presence of sulfate, chloride, municipal water, tert-butanol, and phosphate caused a substantial decrease in TC removal efficiency, reducing it to 3.84%, 3.96%, 4.22%, 6.22%, 6.44%, and 24.4%, respectively. According to Figure 4B, the VUV/H₂O₂ system achieved complete TC removal (100%) in the absence of anions; nevertheless, its efficiency was also notably inhibited by the same anions. In the presence of phosphate, chloride, sulfate, municipal water, and tert-butanol, the TC removal efficiency dropped to 2.74%, 13.4%, 15.6%, 20.6%, and 29.4%, respectively.

The observed inhibition in both processes aligns with previous findings demonstrating that inorganic anions and natural water constituents often act as scavengers of hydroxyl radicals (HO•) or participate in competing side reactions, thereby diminishing the efficiency of AOPs. In the VUV and VUV/H₂O₂ systems, HO• radicals are the dominant oxidizing species responsible for TC degradation. Anions such as phosphate and sulfate readily react with HO•, forming less reactive radical species and consequently lowering the available concentration of HO•. This behavior has been extensively documented in earlier studies. For instance, sulfate ions convert HO• into sulfate radicals (SO₄•⁻), which possess lower oxidation potential and slower reactivity toward organic contaminants. Similarly, chloride reacts with HO• to form chlorine-based radicals (Cl•, Cl₂•⁻), which exhibit weaker oxidizing capabilities, as noted by Pignatello et al. and Serpone et al. (44, 45). The strong inhibitory effect of tert-butanol, an established selective scavenger of HO•, further confirms that hydroxyl radicals are the principal oxidizing species in both systems. Moreover, the reduced TC degradation observed in municipal water highlights the influence of real water matrices, which often contain bicarbonate, natural organic matter (NOM), chloride, phosphate, and other ions that compete for HO• radicals. Similar matrix effects have been reported by Sun et al. and Ribeiro et al., emphasizing that water quality plays a crucial role in AOP performance (46, 47).

Overall, these findings demonstrate that non-target anions significantly suppress TC degradation in both VUV and VUV/H₂O₂ processes, although the inhibitory effect is less pronounced in the VUV/H₂O₂ system due to the continuous photolytic generation of HO• from hydrogen peroxide. The reduction in removal efficiency can be attributed to two primary mechanisms: (A) Direct scavenging of HO• radicals by anions and (B) absorption of UV radiation by the anions, which decreases the formation of HO• available for TC oxidation (27, 33, 48, 49). Representative reactions include:

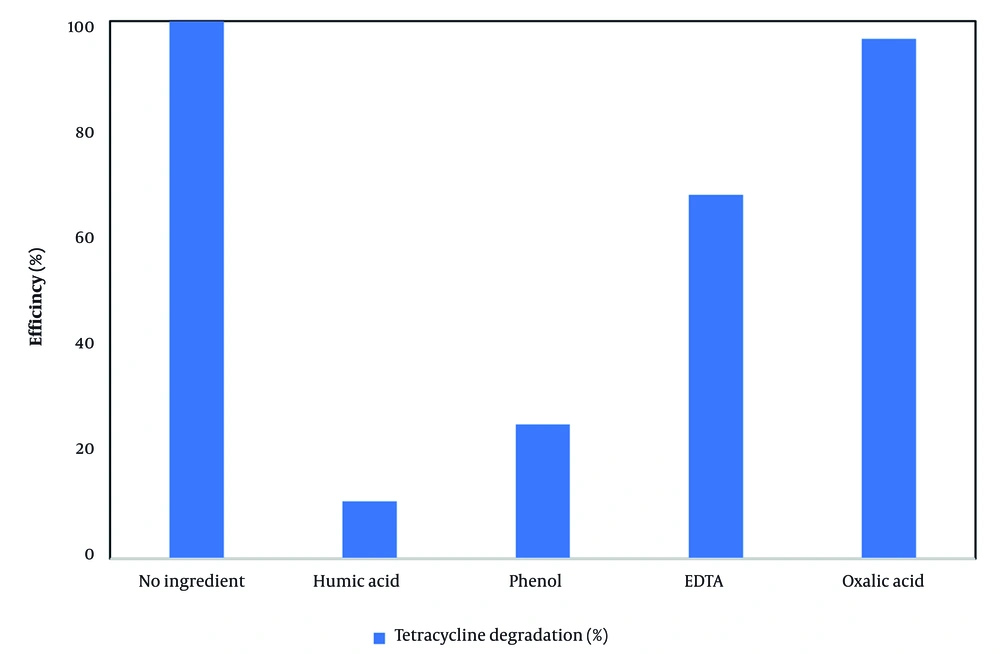

3.5. Effect of Organic Compounds on Degradation of Tetracycline in VUV/H₂O₂ and VUV Process

Under optimal conditions—reaction time of 90 minutes, H₂O₂ concentration of 2 mg/L, pH 7, TC concentration of 10 mg/L, and irradiation wavelength of 359 nm—the effects of various organic compounds, including phenol, EDTA, oxalic acid, and humic acid, were investigated in the VUV/H₂O₂ process. Each organic compound was added at a concentration of 1 mM to 200 mL of TC solution. As illustrated in Figure 5, complete degradation of TC (100%) was achieved in the absence of organic compounds. The presence of these organics, however, decreased the TC removal efficiency as follows: Oxalic acid (96.7%), EDTA (67.7%), phenol (25%), and humic acid (10.7%). Among them, phenol and humic acid exhibited the most pronounced inhibitory effects. This reduction in efficiency is attributed to the competition between the organic molecules and TC for hydroxyl radicals (OH•) generated during the VUV/H₂O₂ process (50).

3.6. Total Organic Carbon and Chemical Oxygen Demand Removal

To further evaluate the effectiveness of the VUV/H₂O₂ process, the removal efficiencies of COD and TOC were examined. The findings demonstrated that both parameters increased steadily with reaction time, achieving maximum removal rates of 78% for COD and 40% for TOC under the optimized conditions. Identifying the final degradation products in AOPs is important because the ideal outcome is the complete mineralization of organic pollutants to CO₂ and H₂O. In this study, the relatively lower COD and TOC reductions compared with the disappearance of the antibiotic suggest that a portion of TC was converted into intermediate compounds rather than being fully mineralized.

3.7. Classification of Different Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Removal of Antibiotics

Table 3 summarizes previous studies that have compared different AOPs for antibiotic degradation. The table includes information on the target antibiotic compounds, removal efficiencies, and key operational parameters such as pH, catalyst dosage, reaction time, and initial contaminant concentrations. As illustrated, the performance of AOPs varies widely depending on the conditions under which they are applied. In this regard, the results of the present work—achieving complete (100%) TC removal under optimized VUV/H₂O₂ conditions—demonstrate the strong capability of this process compared with other reported AOPs.

| Processes | Target Antibiotics | Conditions | Removal (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV/H₂O₂ | Tetracycline (TC) | UV 254 nm; H₂O₂ = 10 - 50 mg/L | 80 - 95% | (51) |

| TiO₂/UV photocatalysis | Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | TiO₂ (0.5 - 1 g/L); UV 365 nm | 75 - 90% | (52) |

| O3/H2O2 process | Amoxicillin (AMX) | O3 flow: 16 mg.h-1; H2O2= 10 μM; T = 20 C | ~100% in all cases | (53) |

| TiO2/UV | Metronidazole (MTR) | TiO2 = 1.5 g/L; UV light intensity = 6.5 mW cm-2 | ~88% in max 30 min | (54) |

| Photo-Fenton processes | Amoxicillin (AMX) | H2O2 = 0.08 mM; Fe3+ = 0.05 mM; Natural solar radiation (pilot-plant Scale CPC photoreactor); pH = 7 - 8 | 90% in 9 min | (55) |

| Photo-fenton processes | Ciprofloxacin (CPR) | H2O2 = 5 - 25 mM; High-pressure mercury lamp 362 nm); T = 25 C; Fe2+ = 0.25 - 2 mM; pH = 2 - 9 | 93% in 45 min | (56) |

| Heterogeneous fenton-like process | Ciprofloxacin (CPR) | H2O2 = 10 - 100 mM; Sludge Biochar Catalyst (SBC) = 0.2g/L; pH = 2 - 12 | 90% in 4 h | (57) |

| VUV/H₂O₂ | Tetracycline (TC) | H₂O₂ = 2 mg/L; Time= 90 min; pH 7 | 100% | This study |

4. Conclusions

The results of this study show that the VUV/H₂O₂ process is highly efficient in removing tetracycline from aqueous solutions. Under the optimized operating conditions (pH 7 and 2 mg/L H₂O₂), complete removal was achieved within 90 minutes. When the H₂O₂ concentration was increased above 10 mg/L, the removal efficiency decreased slightly to about 90.55%, likely due to the scavenging effect associated with excess hydrogen peroxide. In contrast, the VUV process used without H₂O₂ resulted in only about 60% removal, underscoring the significant contribution of H₂O₂ in enhancing degradation. The presence of common anions such as phosphate, chloride, and sulfate reduced the removal efficiency by 29.4%, 13.4%, and 15.6%, respectively. The degradation kinetics were well described by a pseudo-first-order model (R² = 0.9942), suggesting a consistent and predictable reaction pattern. Overall, these findings confirm that the VUV/H₂O₂ system is an effective and environmentally friendly approach for eliminating persistent antibiotics and other pollutants from industrial wastewater. Future studies should further examine its performance in real wastewater conditions, evaluate long-term operational stability, and identify possible degradation intermediates.