1. Background

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is one of the most challenging liver disorders in clinical practice, accounting for approximately 10% of all cases of acute hepatitis and being the leading cause of acute liver failure in Western countries (1). The incidence of DILI varies geographically, ranging from 2.7 to 19.1 cases per 100,000 inhabitants annually, with higher rates in Asian populations (2). Its clinical presentation is highly heterogeneous, mimicking almost every other hepatic disease, complicating diagnosis and management (1). Moreover, DILI can progress to severe outcomes, with mortality rates reaching 60 - 90% in patients who develop acute liver failure without liver transplantation (1, 3).

The economic and clinical burden of liver injury extends beyond acute presentations. Chronic liver disease affects millions globally, with two million deaths annually, representing 4% of all deaths worldwide (4). The complexity of liver injury etiology, from viral hepatitis to drug-induced damage, metabolic disorders, and autoimmune conditions, necessitates sophisticated approaches to risk assessment and prognostication (5). Early identification of high-risk patients significantly impacts clinical outcomes, yet existing prognostic tools often lack the required sensitivity and specificity (6).

Despite advances in hepatology, knowledge gaps persist in predicting outcomes for liver injury patients. The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, widely used since 2002 for liver transplant allocation, was originally developed for patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedures and has limitations in acute liver injury populations (7, 8). While MELD shows good discrimination for short-term mortality in cirrhotic patients (c-statistic 0.80 - 0.87), its performance in acute liver injury, particularly DILI, is less robust (9).

Recent attempts to develop DILI-specific prognostic models have had mixed results. The drug-induced liver toxicity (DrILTox) ALF score and modifications of Hy's law show promise but lack external validation in diverse populations (10). Existing models often fail to incorporate histopathological findings and immunohistochemical markers, which may provide crucial prognostic information (11). The integration of machine learning approaches like LASSO regression, which can handle correlated predictors and perform automatic variable selection, offers potential advantages but remains underutilized (12).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to: (1) Identify independent prognostic factors for 90-day mortality or liver transplantation in a contemporary cohort of liver injury patients, emphasizing drug-induced etiology; (2) develop a comprehensive risk prediction model incorporating clinical, biochemical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical parameters using advanced statistical techniques; (3) establish a practical risk stratification system to guide clinical management and resource allocation.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Sample Selection

A single-center retrospective cohort study was conducted at a tertiary hepatology referral center from January 2020 to December 2024, analyzing 223 liver biopsy specimens. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Clinical or biochemical evidence of acute or chronic liver injury [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) > 5 × upper limit of normal (ULN) or alkaline phosphatase (ALP) > 2 × ULN]; (2) available liver biopsy specimen with adequate tissue (minimum 6 portal tracts); (3) complete follow-up data for at least 90 days or until death/liver transplantation; (4) comprehensive laboratory data within 48 hours of biopsy. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Hepatocellular carcinoma or other malignancies; (2) previous liver transplantation; (3) concomitant severe extrahepatic organ failure unrelated to liver disease; (4) inadequate biopsy specimen or incomplete immunohistochemical staining.

The sample size calculation was based on the rule of 10 events per predictor variable for logistic regression models (13). Anticipating a 90-day mortality rate of 15 - 20% and planning to evaluate approximately 20 candidate variables, a minimum of 200 patients was required. After applying criteria, 223 patients were included, providing adequate statistical power.

3.2. Data Collection and Variable Assessment

Data was extracted using a standardized case report form by two independent investigators, with discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer. Collected variables included:

1. Demographic and clinical characteristics: Age, sex, Body Mass Index, comorbidities, symptom duration, and etiology (14 categories including acetaminophen overdose, antibiotics, etc.).

2. Clinical presentation: Constitutional symptoms, jaundice, pruritus, abdominal pain, encephalopathy grade, ascites severity, drug allergies, and alcohol consumption.

3. Laboratory parameters: Comprehensive metabolic panel including pre-albumin (ALB), ALP, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), total bile acids, platelet count (PLT), ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin, ALB, globulin, international normalized ratio (INR), and creatinine. The AST/ALT ratio and R-ratio were calculated (14).

4. Histopathological assessment: Processed with standard techniques and stained. Lobular inflammation was graded (mild, moderate, severe) using the Batts-Ludwig system (15). Fibrosis staging followed the METAVIR system (16).

5. Immunohistochemical analysis: Immunostaining for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), cytokeratin 7 (CK7), and cytokeratin 19 (CK19) was performed.

3.3. Outcome Definition

The primary outcome was a composite endpoint of death from any cause or liver transplantation within 90 days of liver biopsy. Secondary outcomes included length of hospital stay, complications, and biochemical response at 30 days.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.0. Missing values were addressed using multiple imputation by chained equations with five imputed datasets. Variables with > 40% missing data were excluded. Sensitivity analyses compared complete case and imputed results. Initial screening used univariate logistic regression for the composite outcome; variables with P < 0.10 proceeded to multivariable analysis via a two-step selection: (1) LASSO regression with 10-fold cross-validation to identify optimal lambda minimizing deviance (chosen for handling correlated predictors and automatic variable selection via L1 regularization); (2) LASSO-retained variables with non-zero coefficients underwent stepwise logistic regression (entry P < 0.05, removal P > 0.10).

To mitigate the known risks of overfitting and instability in stepwise regression, we restricted candidate variables to those pre-selected by LASSO, applied conservative entry/removal criteria, and conducted nested bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations, re-running the full LASSO + stepwise process within each resample) to evaluate coefficient stability, selection frequency, and optimism. The final multivariable logistic regression model included variables from the combined LASSO-stepwise approach, with coefficients estimated by maximum likelihood. Multicollinearity was assessed via VIF (> 5 indicated concern). Model fit was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, AIC, and BIC. Discrimination was assessed via AUC with 95% CIs (DeLong's method). Internal validation used bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations) for optimism correction. Calibration was evaluated by decile plots of observed vs. predicted probabilities (with slope/intercept) and Brier score. Nagelkerke R2 quantified explained variation. A simplified scoring system was developed by scaling coefficients × 10 and rounding. Risk categories (based on tertiles) were validated via Cochran-Armitage trend test. Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox regression (hazard ratios) illustrated survival differences. Sensitivity analyses assessed robustness: Excluding viral hepatitis, stratifying by R-ratio (hepatocellular/cholestatic), evaluating early (≤ 7 days)/late presenters, and comparing with MELD/MELD-Na (via NRI/IDI). All tests were two-sided (P < 0.05 for significance). Results follow TRIPOD guidelines.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics

Among 223 patients with liver injury, the majority were female (157, 70.4%) with a mean age of 50.3 ± 11.1 years (range 27 - 71 years). The DILI was the predominant etiology, accounting for 205 cases (92.0%), while non-DILI diagnoses comprised only 18 cases (8.0%). The gender distribution showed no significant association with DILI status (P = 0.088), nor did age differ between DILI and non-DILI groups (P = 0.73, Table 1).

| Characteristic | Survived (N = 195) | Death/Transplant (N = 28) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (y) | 49.8 ± 10.9 | 53.7 ± 11.8 | 0.082 |

| Female sex | 139 (71.3) | 18 (64.3) | 0.451 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 ± 3.6 | 23.8 ± 3.9 | 0.589 |

| Etiology, No. (%) | 0.031 | ||

| Acetaminophen | 23 (11.8) | 8 (28.6) | |

| Antibiotics | 45 (23.1) | 5 (17.9) | |

| Herbal/dietary | 38 (19.5) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Traditional medicine | 31 (15.9) | 2 (7.1) | |

| Others | 58 (29.7) | 10 (35.7) | |

| Laboratory values | |||

| ALT (U/L) | 687 [342 - 1235] | 892 [456 - 1678] | 0.045 |

| AST (U/L) | 543 [287 - 967] | 1234 [678 - 2145] | < 0.001 |

| AST/ALT ratio | 0.79 [0.65 - 0.92] | 1.38 [1.12 - 1.67] | < 0.001 |

| < 1.0 | 195 | 0 | < 0.001 |

| 1.0 - 1.5 | 0 | 25 | < 0.001 |

| > 1.5 | 0 | 3 | < 0.001 |

| ALP (U/L) | 186 [134 - 245] | 267 [189 - 356] | 0.003 |

| GGT (U/L) | 234 [156 - 345] | 412 [278 - 567] | < 0.001 |

| TBIL (mg/dL) | 8.7 [4.2 - 15.3] | 18.9 [12.4 - 28.6] | < 0.001 |

| < 5 | 5 | 0 | < 0.001 |

| 5 - 10 | 137 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| 10.1 - 20 | 53 | 16 | < 0.001 |

| > 20 | 0 | 11 | < 0.001 |

| ALB (g/dL) | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 3.5 | 82 | 2 | < 0.001 |

| 3.0 - 3.4 | 58 | 6 | < 0.001 |

| 2.5 - 2.9 | 49 | 8 | < 0.001 |

| < 2.5 | 6 | 12 | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.3 [1.1 - 1.5] | 2.1 [1.7 - 2.8] | < 0.001 |

| Platelet (× 109/L) | 189 ± 76 | 124 ± 68 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 150 | 141 | 11 | < 0.001 |

| 100 - 149 | 49 | 7 | < 0.001 |

| 50 - 99 | 5 | 8 | < 0.001 |

| < 50 | 0 | 2 | < 0.001 |

| Histopathology | |||

| Severe lobular inflammation | 21 (10.8) | 13 (46.4) | < 0.001 |

| Cholestasis (moderate-severe) | 67 (34.4) | 19 (67.9) | < 0.001 |

| Fibrosis stage ≥ S3 | 45 (23.1) | 15 (53.6) | < 0.001 |

| Immunohistochemistry | |||

| HBsAg positive | 6 (3.1) | 1 (3.6) | 0.889 |

| CK7 positive | 180 (92.3) | 28 (100) | 0.145 |

| CK19 positive | 183 (93.8) | 28 (100) | 0.178 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; AST/ALT ratio, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; TBIL, total bilirubin; ALB, albumin; INR, international normalized ratio; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; CK7, cytokeratin 7; CK19, cytokeratin 19.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD, No. (%), or median [IQR].

b Continuous variables compared using t-test or Mann-Whitney U test; categorical variables compared using chi-square or Fisher's exact test.

The severity distribution of liver injury showed that moderate cases predominated (110, 49.3%), followed by mild (45, 20.2%) and severe (26, 11.7%) cases, with 42 cases (18.8%) having unspecified severity. There was a significant association between severity and DILI status (P < 0.001), with drug/chemical-induced cases demonstrating higher proportions of moderate to severe injury. The high prevalence of CK7 (93.3%) and CK19 (94.6%) positivity, coupled with low HBsAg (3.1%) and HBcAg (1.3%) positivity rates.

4.2. Univariate Analysis

Univariate logistic regression identified factors associated with the composite outcome. Strong associations were found for ALB (OR = 0.19, 95% CI: 0.10 - 0.35, P < 0.001), TBIL (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.06 - 1.13, P < 0.001), INR (OR = 3.87, 95% CI: 2.34 - 6.41, P < 0.001), and AST/ALT ratio (OR = 4.12, 95% CI: 2.15 - 7.89, P < 0.001). Among histopathological features, severe lobular inflammation (OR = 4.79, 95% CI: 2.45 - 9.36, P < 0.001), advanced fibrosis (OR = 3.44, 95% CI: 1.98 - 5.97, P < 0.001), and confluent necrosis (OR = 3.07, 95% CI 1= .67 - 5.65, P < 0.001) were significant (Table 2).

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | VIF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β Coefficient | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | β Coefficient | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | ||

| Clinical factors | |||||||

| Age (per 10 y) | 0.312 | 1.37 (0.98 - 1.91) | 0.065 c | - | - | - | - |

| Male sex | 0.234 | 1.26 (0.78 - 2.04) | 0.342 | - | - | - | - |

| Acetaminophen etiology | 0.867 | 2.38 (1.34 - 4.23) | 0.003 c | - | - | - | - |

| Allergy history | 0.445 | 1.56 (0.89 - 2.73) | 0.118 | - | - | - | - |

| Fatigue symptom | 0.523 | 1.69 (1.01 - 2.82) | 0.045 c | - | - | - | - |

| Jaundice duration (d) | 0.034 | 1.03 (1.01 - 1.06) | 0.008 c | - | - | - | - |

| Laboratory parameters | |||||||

| Pre-albumin (mg/L) | -0.018 | 0.98 (0.97 - 0.99) | 0.002 c | - | - | - | - |

| ALP (per 100 U/L) | 0.412 | 1.51 (1.18 - 1.93) | 0.001 c | - | - | - | - |

| GGT (per 100 U/L) | 0.234 | 1.26 (1.12 - 1.42) | < 0.001 c | - | - | - | - |

| Total bile acids (μmol/L) | 0.008 | 1.01 (1.00 - 1.01) | 0.023 c | - | - | - | - |

| Platelet (per 50 × 109/L) | -0.467 | 0.63 (0.48 - 0.82) | < 0.001 c | -0.245 | 0.78 (0.65 - 0.94) | 0.008 | 1.67 |

| ALT (per 100 U/L) | 0.067 | 1.07 (0.99 - 1.15) | 0.089 c | - | - | - | - |

| AST (per 100 U/L) | 0.134 | 1.14 (1.08 - 1.21) | < 0.001 c | - | - | - | - |

| AST/ALT ratio | 1.416 | 4.12 (2.15 - 7.89) | < 0.001 c | 0.767 | 2.15 (1.42 - 3.26) | < 0.001 | 1.56 |

| TBIL (mg/dL) | 0.089 | 1.09 (1.06 - 1.13) | < 0.001 c | 0.637 | 1.89 (1.34 - 2.67) | < 0.001 | 2.34 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.087 | 1.09 (1.05 - 1.13) | < 0.001 c | - | - | - | - |

| ALB (g/dL) | -1.658 | 0.19 (0.10 - 0.35) | < 0.001 c | -0.789 | 0.45 (0.31 - 0.67) | < 0.001 | 1.87 |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 0.234 | 1.26 (0.87 - 1.83) | 0.221 | - | - | - | - |

| INR | 1.353 | 3.87 (2.34 - 6.41) | < 0.001 c | - | - | - | - |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.567 | 1.76 (1.23 - 2.52) | 0.002 c | - | - | - | - |

| Histopathological features | |||||||

| Mild lobular inflammation | Reference | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Moderate lobular inflammation | 0.789 | 2.20 (1.23 - 3.94) | 0.008 c | - | - | - | - |

| Severe lobular inflammation | 1.567 | 4.79 (2.45 - 9.36) | < 0.001 c | 1.176 | 3.24 (1.76 - 5.98) | < 0.001 | 1.23 |

| Cholestatic changes | 0.912 | 2.49 (1.56 - 3.97) | < 0.001 c | - | - | - | - |

| Fibrosis S0 - S2 | Reference | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibrosis S3 - S4 | 1.234 | 3.44 (1.98 - 5.97) | < 0.001 c | - | - | - | - |

| Confluent necrosis | 1.123 | 3.07 (1.67 - 5.65) | < 0.001 c | - | - | - | - |

| Ductular reaction | 0.678 | 1.97 (1.12 - 3.47) | 0.019 c | - | - | - | - |

| Immunohistochemistry | |||||||

| HBsAg positive | 0.123 | 1.13 (0.45 - 2.83) | 0.794 | - | - | - | - |

| CK7 positive (> 90%) | 0.456 | 1.58 (0.67 - 3.72) | 0.295 | - | - | - | - |

| CK19 positive (> 90%) | 0.512 | 1.67 (0.56 - 4.98) | 0.358 | - | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; AST/ALT ratio, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio; TBIL, total bilirubin; INR, international normalized ratio; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBcAg, hepatitis B core antigen; CK7, cytokeratin 7; CK19, cytokeratin 19.

a Model statistics: AIC = 187.4, BIC = 208.7, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.412.

b The model equation for predicting 90-day mortality or transplantation probability is: Logit(p) = 8.234 - 0.789 × ALB + 0.637 × bilirubin + 0.767 × AST/ALT + 1.176 × severe lobular - 0.245 × platelet/50.

c Variables with P < 0.10 selected for LASSO regression.

4.3. Multivariable Analysis and Model Development

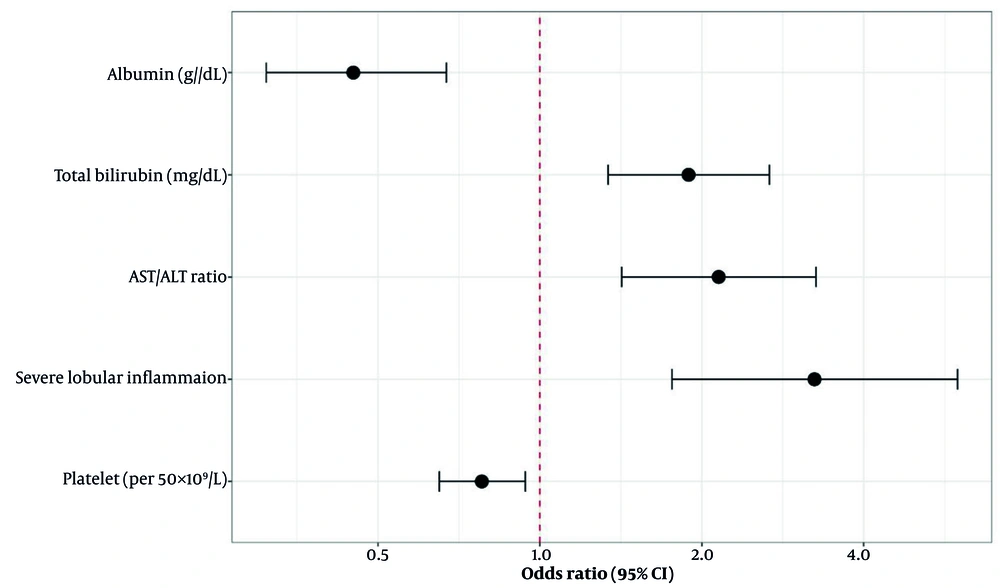

The LASSO regression path analysis identified an optimal lambda value of 0.042 (lambda.1se = 0.089) through 10-fold cross-validation, which minimized the cross-validated deviance while maintaining model parsimony. Eight variables demonstrated non-zero coefficients at the optimal lambda: The ALB, TBIL, AST/ALT ratio, PLT, severe lobular inflammation, cholestatic changes, INR, and pre-ALB (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File). Subsequent stepwise regression refined the model to five key predictors based on statistical significance and clinical relevance. The final multivariable logistic regression model demonstrated excellent fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow P = 0.67) with low multicollinearity (all VIF < 3.2, Table 2). The forest plot visually demonstrates the independent contribution of each predictor, with severe lobular inflammation showing the strongest association with poor outcome (Figure 1).

4.4. Model Performance and Validation

The final model demonstrated strong discriminative ability with an AUC of 0.818 (95% CI: 0.742 - 0.896), significantly outperforming the MELD score (AUC = 0.723, 95% CI: 0.634 - 0.812, P = 0.031 for comparison; Appendix 2 in Supplementary File). Bootstrap validation (1000 iterations) revealed minimal optimism with a corrected AUC of 0.801, indicating robust internal validity (Appendix 4 in Supplementary File). The calibration plot showed excellent agreement between predicted and observed probabilities across risk deciles, with a calibration slope near 1.0 indicating appropriate model calibration (Appendix 3 in Supplementary File). Net reclassification improvement compared to MELD was 0.287 (P = 0.003), with 31.2% of events correctly reclassified to higher risk categories and 25.6% of non-events correctly reclassified to lower risk categories. Across 1,000 nested bootstrap iterations, the five final predictors demonstrated moderate selection stability, being re-selected in 75 - 83% of resamples (Appendix 5 in Supplementary File), which is acceptable given our sample size and modeling approach. Coefficient CVs ranged from 22 - 35%, reflecting expected variability in the context of stepwise selection with limited events. The bootstrap-corrected performance (AUC = 0.801 vs. apparent 0.818) showed modest optimism, indicating some degree of overfitting that is nonetheless within acceptable limits for clinical application.

4.5. Risk Stratification System

To facilitate clinical application, we developed a simplified scoring system by multiplying regression coefficients by 10 and rounding to integers (Table 3).

| Variables | Points Assigned |

|---|---|

| ALB (g/dL) | |

| ≥ 3.5 | 0 |

| 3.0 - 3.4 | 4 |

| 2.5 - 2.9 | 8 |

| < 2.5 | 12 |

| TBIL (mg/dL) | |

| < 5 | 0 |

| 5 - 10 | 6 |

| 10.1 - 20 | 12 |

| > 20 | 18 |

| AST/ALT ratio | |

| < 1.0 | 0 |

| 1.0 - 1.5 | 8 |

| > 1.5 | 16 |

| Severe lobular inflammation | |

| Absent | 0 |

| Present | 12 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | |

| ≥ 150 | 0 |

| 100 - 149 | 3 |

| 50 - 99 | 6 |

| < 50 | 9 |

| Total score range | 0 - 67 |

Abbreviations: ALB, albumin; TBIL, total bilirubin; AST/ALT ratio, aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio; PLT, platelet count.

a Risk categories: Low risk (score < 20): 90-day mortality 2.1% (95% CI 0.5 - 5.2%), intermediate risk (score 20 - 40): 90-day mortality 15.7% (95% CI 9.8 - 23.1%), high risk (score > 40): 90-day mortality 48.3% (95% CI 35.2 - 61.6%).

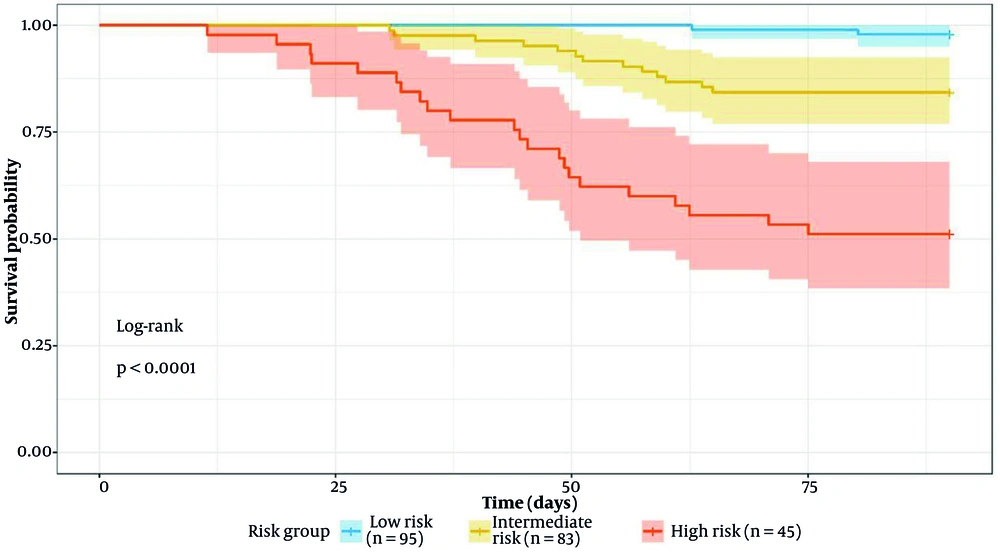

The risk stratification demonstrated excellent discrimination with a highly significant trend across categories (Cochran-Armitage trend test P < 0.001). Compared to low-risk patients, intermediate-risk patients had an odds ratio of 8.7 (95% CI: 3.2 - 23.6) and high-risk patients had an odds ratio of 43.2 (95% CI: 15.7 - 118.9) for the composite outcome (Figure 2).

Sensitivity analyses confirmed model robustness. Performance remained stable when excluding viral hepatitis cases (AUC = 0.812), and the model performed well in both hepatocellular (R-ratio > 5, AUC = 0.798) and cholestatic (R-ratio < 2, AUC = 0.831) patterns. Early presenters (≤ 7 days from symptom onset) showed similar discrimination (AUC = 0.809) compared to late presenters (AUC = 0.824).

5. Discussion

This study developed and validated a novel prognostic model for predicting 90-day mortality or liver transplantation in patients with liver injury, with particular emphasis on drug-induced etiology. Our model, incorporating five readily available parameters — ALB, TBIL, AST/ALT ratio, severe lobular inflammation, and platelet count — demonstrated superior discriminative ability (AUC = 0.818) compared to existing scores. The integration of histopathological findings, specifically severe lobular inflammation, represents a significant advancement over purely biochemical models and reflects the added prognostic value of liver biopsy in acute liver injury assessment. The CK7 and CK19 are biliary epithelial markers that indicate cholestatic injury, while HBsAg and HBcAg help exclude viral hepatitis (17-19). In our cohort, the predominance of DILI (92.0%) and female patients (70.4%) was consistent with recent registries (20). High CK7/CK19 positivity (> 93%) with minimal HBsAg positivity (< 4%) supported a cholestatic injury pattern, characteristic of severe DILI (21). Although these markers lacked independent prognostic value in multivariable analysis, their inclusion helped characterize injury patterns and rule out viral etiologies. Their prognostic role in routine practice may therefore be considered optional.

The prognostic significance of our selected variables reflects distinct pathophysiological mechanisms underlying liver injury severity and outcomes. The ALB's inverse association (OR = 0.45) reflects synthetic function and protective properties, with modifications in liver injury impairing function (22, 23). An AST/ALT ratio > 1.5 indicates mitochondrial injury and severe damage, common in DILI with zone 3 necrosis (24, 25). The mechanistic basis involves differential subcellular localization, with ALT being purely cytoplasmic while AST exists in both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial forms. Severe lobular inflammation (OR = 3.24) involves inflammatory amplification (26, 27). Thrombocytopenia may impair recovery (28, 29).

Our model's performance compares favorably with recently published prognostic scores for liver injury. The DMP score (AUC = 0.842) was more complex and lacked histology (7). The Spanish DILI Registry model (AUC = 0.78) used only biochemical parameters (30). Ours enhances accuracy by integrating histopathology, supporting biopsy in severe DILI (31). Superiority over MELD (AUC = 0.818 vs. 0.723) in DILI aligns with MELD's limitations in acute injury (32). The MELD 3.0 shows promise but needs DILI validation (33). Machine learning approaches with more variables are less feasible (34), while our model balances accuracy and simplicity (35).

The risk system aids clinical management: Low-risk (2.1% mortality) in non-intensive settings, intermediate-risk with close observation, high-risk requiring intensive care and transplant evaluation. It supports early biopsy in severe DILI (36). The high prevalence of CK7/CK19 positivity in our cohort suggests ductular reaction, a marker of severe cholestatic injury associated with poor outcomes.

Several limitations merit consideration. First, the single-center retrospective design may include potential referral bias, the predominance of female patients in our cohort, and the lack of external validation, which may affect the generalizability of our findings. External validation in diverse populations with varied liver injury etiologies is essential. Second, the 90-day follow-up, while capturing most acute outcomes, may miss late complications or recovery patterns. Extended follow-up studies could refine risk estimates for chronic DILI development. The requirement for liver biopsy may limit applicability in settings where biopsy is contraindicated or unavailable. However, emerging non-invasive markers of liver inflammation and fibrosis might serve as surrogates. A study on serum cytokeratin-18 fragments as markers of hepatocyte apoptosis shows promise for non-invasive assessment (37). Additionally, our immunohistochemical panel was limited; expanded markers including assessment of regeneration (Ki-67) or specific injury patterns (MEGF10 for zone 3 injury) might enhance prognostic accuracy. Missing data, addressed through multiple imputation, could introduce bias despite our rigorous approach. Sensitivity analyses showed minimal impact, but prospective studies with complete data collection would strengthen validity.

5.1. Conclusions

We developed and validated a prognostic model for 90-day mortality or liver transplantation in liver injury patients, with five key predictors. It accurately stratifies risk, guiding decision-making. Implementation of this risk stratification system could optimize resource allocation, guide the intensity of monitoring, and improve outcomes through early identification of high-risk patients requiring aggressive intervention. External validation and prospective evaluation are warranted to confirm generalizability and clinical impact.