1. Background

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer in women and the second most common malignancy worldwide (1, 2), and in 2020, about 2.3 million new cases were estimated globally (3). In the United States, nearly 287,850 new cases of female and 2,710 new cases of aggressive male BC were diagnosed in 2022 (4). According to ASMR overall, BC is projected to decrease by 7% in East Asia by 2030 compared to 1990, from 9/10 cases per 100,000 to 9.88 cases per 100,000, and 35% in South Asia from 13/4 (5). In 2022, a nationwide study showed that overall survival in BC patients in Iran has improved (5-year survival increased from 71% in 2011 to 80%), which is likely due to advances in cancer care (6). Breast cancer mainly involves the inner layers of mammary glands or lobules and ducts (7). Breast cancer staging, assessed through the tumor, node, metastasis system (TNM), is integral for treatment planning and prognosis. Ranging from 0 to 4, stages indicate the extent of the primary tumor, lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis especially for treatment and prognosis (8). Since more than 50% of patients with this disease died, increasing the survival rate of these patients by determining the stage of the disease is of great importance (9). The earlier the stage is identified, the better the survival rate (10). Breast cancer is influenced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors (11).

Breast cancer, a heterogeneous malignancy, presents diverse molecular features that influence its behavior and prognosis (11). Among genetic factors involved in BC, BRCA2 plays a key role as a recessive tumor suppressor gene. Located on chromosome 12q13, BRCA2 is primarily involved in homologous recombination and DNA repair, contributing to genomic stability. While BRCA2 mutations are well-linked to BC risk, its gene expression patterns remain less explored (12). BRCA2 expression is often higher in more aggressive cancers, correlating with estrogen receptor negativity and higher histological grade (13). Both BRCA1 expression and cancer antigen 15-3 (CA15-3) levels increase significantly with advanced cancer stages (14). Interestingly, some cases show an inverse correlation between BRCA1 and BRCA2 expression, suggesting a potential compensatory mechanism (15). A member of the mucin-1 (MUC-1) glycoprotein family is the carcinoembryonic antigen (CA15-3), which is known as a useful tumor marker and is overexpressed in cancers, where it is increased by its reconstituted glycosylation (16). Since CA15-3 is a slowly glycosylated protein, glycosylation changes have great potential to indicate carcinogenesis and prognosis effectively (17).

The relationship between CA15-3 and BRCA2 in BC grades is intricate (18). The CA15-3 may reflect tumor burden and potentially correlate with higher-grade tumors (19). BRCA2 mutations may influence tumor characteristics (19). Understanding their interplay could provide insights into disease dynamics, guiding personalized treatment approaches (20).

2. Objectives

Research to identify biomarkers is still ongoing; as a result, the present study aimed to comparatively evaluate BRCA2 gene expression and tumor marker CA15-3 in BC grades. By identifying molecular and serum patterns associated with the degree of tumor progression, this research aids in early diagnosis, determines the disease’s precise stage, and enables personalized treatment planning, ultimately helping to reduce mortality and improve patient survival.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on 70 women diagnosed with BC who were referred to the Cancer Research Center of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, between January and December 2021. All participants had a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of invasive breast carcinoma, established through core-needle biopsy or surgical resection specimens, and independently verified by two experienced pathologists at Shohadaye Tajrish Hospital. Only patients with complete clinical and pathological records were included. Eligible participants were women aged 30 - 83 years with no prior history of cancer or anticancer treatment (including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormonal therapy) and who had not received neoadjuvant therapy prior to sample collection. Exclusion criteria included: (1) History of prior malignancy; (2) incomplete medical or pathological documentation; (3) insufficient blood volume for both RNA extraction and CA15-3 analysis; and (4) inconclusive pathology reports — defined as specimens with inadequate tumor tissue, ambiguous histological features, or failure to confirm carcinoma on central review. All enrolled cases were treatment-naive at the time of sampling to avoid confounding effects on biomarker expression.

3.1. Sampling

First, an experienced and skilled nurse, using a sterile syringe, and 5 cc blood samples and 5 cc serum samples were taken from women with BC whose pathology tests were approved by a specialist doctor. Then, the serum samples were transferred to the immunology laboratory in order to check the CA15-3 tumor marker in the transport environment, and at the same time, the blood samples were transferred to the molecular laboratory to check the BRCA2 gene.

3.2. Staging

Histopathological evaluation was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Tumor grading was assessed using the Nottingham grading system, based on tubule formation, nuclear pleomorphism, and mitotic count. Scores (1 - 3 for each parameter) were summed to classify tumors as grade 1 (3 - 5), grade 2 (6 - 7), or grade 3 (8 - 9). Pathological staging was determined according to the 8th edition of the AJCC TNM system, evaluating tumor size (T), lymph node status (N), and metastasis (M). All evaluations were carried out by experienced pathologists at Shohadaye Tajrish Hospital, blinded to molecular data, to ensure unbiased assessment.

3.3. RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from whole blood samples using the NucleoSpin® RNA Blood Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany; Cat. No: 740965.250) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Although RNA concentration was not quantified using spectrophotometric or fluorometric methods due to limited sample volume and immediate downstream processing constraints, standardization across samples was ensured through consistent input volume of blood (200 µL per extraction) and uniform processing conditions. Furthermore, to minimize technical variability and ensure comparability in downstream applications (e.g., RT-qPCR), equal volumes of eluted RNA (4 µL) were used for reverse transcription across all samples. The integrity of the extracted RNA was confirmed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, which demonstrated intact ribosomal RNA bands (28S and 18S) with a clear 2:1 intensity ratio, indicating acceptable RNA quality for subsequent analyses.

3.4. The cDNA Synthesis

To eliminate DNA contamination, DNase I treatment was performed. A DNase reagent (Sinnaclon and Cat. MO5401, Iran) was utilized following the manufacturer’s instructions, ensuring the prevention of genomic DNA contamination and minimizing nonspecific binding. For cDNA synthesis, the TOPscript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Cat. RT001, Korea) was employed. For each reaction, 1 μg of RNA sample was employed. The treated RNA was subsequently subjected to reverse transcription utilizing random hexamer primers and the cDNA synthesis kit, as instructed.

3.5. Primer Design and Real-time PCR

In this study, the BRCA2 gene was selected as the target gene, while GAPDH was used as the internal reference (housekeeping) gene for normalization purposes. Gene-specific primers were designed based on gene sequences obtained from reliable databases, including NCBI, HGNC, and GeneCards. The primer design process involved sequence comparison and alignment using Clustal Omega and Gene Runner softwares to ensure specificity and compatibility. Primer specificity was further confirmed by BLASTN analysis against the human genome database. For real-time PCR, 1 μL of synthesized cDNA was used as a template in a 20 μL reaction volume containing 10 μL of SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix 2X (Yekta-Tajhiz-Azma, Iran). All reactions were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and accuracy of the results. Amplification was carried out on a real-time PCR detection system with the following thermal cycling protocol: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 minute. A melting curve analysis was conducted at the end of amplification to verify the specificity of the amplified products by assessing their dissociation profiles. Furthermore, primer efficiency was validated through standard curve analysis using serial dilutions of cDNA, achieving amplification efficiencies within the acceptable range of 90 - 110% and an R2-value > 0.99, ensuring accurate and reproducible quantification of BRCA2 gene expression (Table 1).

| Regions and Oligonucleotide Primers (5’ to 3’) | Primers | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| Exon 11 (BRCA2) | ||

| CGAGGCATTGGATGATTCAGAG | F | 394 |

| GAGCTGGTCTGAATGTTCGTTAC | R | |

| GAGAAACCCAGAGCACTGTG | F | 404 |

| CTAAGATAAGGGGCTCTCCTC | R | |

| CGAGGCATTGGATGATTCAGAG | F | 394 |

| GAGCTGGTCTGAATGTTCGTTAC | R | |

| Exon 17 (BRCA2) | ||

| GTAGTTGTTGAATTCAGTATC | F | 354 |

| TGGCAACTGTCACTGACAAC | R | |

| GAPDH | ||

| CGACCACTTTGTCAAGCTCA | F | 183 |

| AGGGGTCTACATGGCAACTG | R |

3.6. Measurement of Tumor Marker Cancer Antigen 15-3

The CA15-3 serum levels were measured by an automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay system with a kit (ROCHE E170; Roche, Germany). Cutoff points for tumor marker CA15-3 above 25 μg/L are considered high levels.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

The CT values attained from RT-qPCR were utilized in the 2-ΔΔCT method to determine the relative fold expression change. To describe the quantitative variables, if the distribution is normal, the mean and standard deviation, and if it is not normal, the interquartile range (IQR) and the median, and for the qualitative variables, the number (percentage) was reported. Chi-square test was used to compare BRCA2 gene expression according to different variables and also based on different stages of cancer. Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests were applied to compare the mean of tumor marker CA15-3 according to different variables and also based on different stages of cancer. Data were analyzed using Stata software (version 14). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

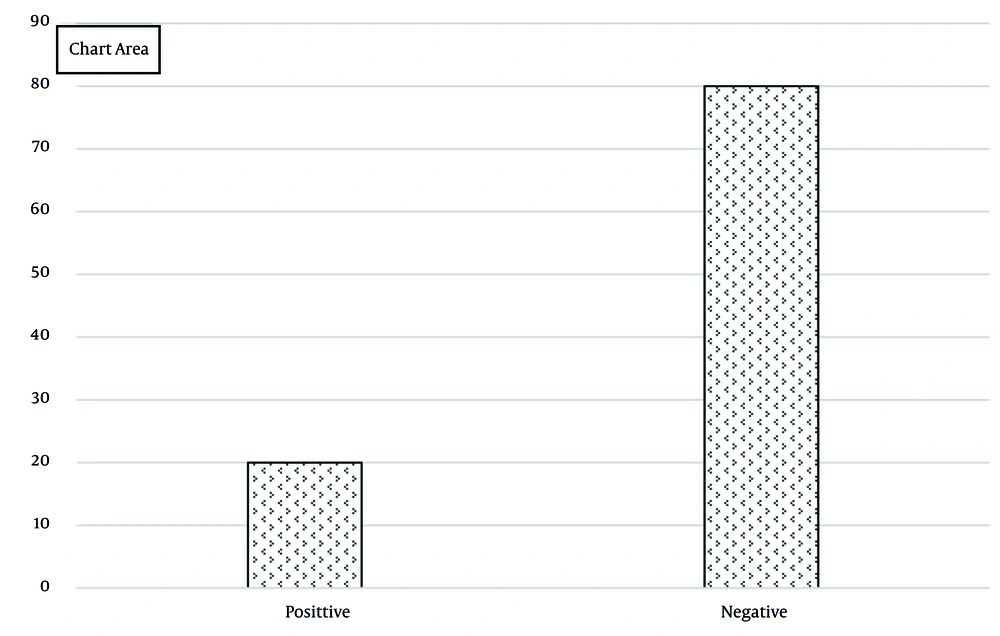

In this study, 70 patients with BC were assessed (mean age: 58.84 ± 11.67 years, range: 30 - 83 years). Notably, 77.14% of patients were aged over 50, 86.22% had a history of BC, 18.57% had a history of ovarian cancer, and 35.71% had a family history of cancer. The distribution of cancer stages ranged from +1 (54.29%) to +4 (2.86%, Table 2). BRCA2 gene was expressed in 20% of patients (n = 14) and was negative in 80% (Figure 1). The mean CA15-3 tumor marker levels were 157.30 ± 255.96 with a range of 18.7 to 1000 μg/L. In patients below 50 years, BRCA2 expression was 7.14%, lower than the group equal to/over 50 years (23.21%). Gene expression was significantly higher in cases who had a history of breast and ovarian cancer (P < 0.05). Additionally, gene expression was more frequent in patients with a family history of cancer (55% vs. 6%; P < 0.001, Table 3). The median CA15-3 tumor marker in patients under 50 years was not significantly different from those aged 50 years or older (P = 0.58). However, it was significantly higher in cases who had a history of ovarian and BC, and family history of cancer (P < 0.001). Regarding BRCA2 gene expression, the median CA15-3 was 675 in positive expression and 36.4 μg/L in negative expression, showing statistical significance (P < 0.001, Table 4). BRCA2 gene expression showed the highest frequency at stage +3 (45.45%), followed by +2 (22.22%), and lowest at +1 (4.55%). Expression significantly increased with advancing disease stage (P = 0.04). Similarly, CA15-3 mean levels were highest at stage +3 (150 μg/L), followed by +2 (40.3 μg/L), and lowest at +1 (34 μg/L). The CA15-3 mean levels significantly increased with higher disease stages (P < 0.001; Table 5).

| Different Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Age categories (y) | |

| Less than 50 | 14 (20) |

| Equal to/more than 50 | 56 (80) |

| BC history | |

| Yes | 15 (21.43) |

| No | 55 (78.57) |

| Ovarian cancer history | |

| Yes | 12 (17.14) |

| No | 58 (82.86) |

| Family history of cancer | |

| Yes | 20 (28.57) |

| No | 50 (71.43) |

| Stage of BC | |

| +1 | 22 (31.43) |

| +2 | 36 (51.43) |

| +3 | 11 (15.71) |

| +4 | 1 (1.43) |

Abbreviation: BC, breast cancer.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

| Different Variables | Positive (N = 14) | Negative (N = 56) | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age categories (y) | 0.17 | ||

| Less than 50 | 1 (7.14) | 13 (92.68) | |

| Equal to/more than 50 | 13 (23.21) | 43 (76.79) | |

| BC history | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1 (6.67) | 314 (93.33) | |

| No | 55 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Ovarian cancer history | 0.004 | ||

| Yes | 6 (50) | 6 (50) | |

| No | 8 (13.79) | 50 (86.21) | |

| Family history of cancer | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 11 (55) | 9 (45) | |

| No | 3 (6) | 47 (94) |

Abbreviation: BC, breast cancer.

a Values are expressed No. (%).

b Based on chi-square test.

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Range | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age categories (y) | 0.58 | |||

| Less than 50 (n = 14) | 101.63 ± 203.76 | 37.15 (19.3) | 28 - 800 | |

| Equal to/more than 50 (n = 56) | 171.22 ± 267.19 | 45.1 (116.62) | 18.7 - 1000 | |

| BC history | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes (n = 15) | 558.32 ± 315.52 | 652 (587) | 92.8 - 1000 | |

| No (n = 55) | 47.93 ± 32.42 | 35.8 (25) | 18.7 - 158 | |

| Ovarian cancer history | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes (n = 12) | 289.05 ± 276.11 | 169 (345.9) | 26.4 - 800 | |

| No (n = 58) | 130.04 ± 245.32 | 37.3 (39) | 18.7 - 1000 | |

| Family history of cancer | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes (n = 20) | 368.66 ± 334.39 | 195.5 (580.2) | 28 - 1000 | |

| No (n = 50) | 72.76 ± 158.87 | 35 (18.8) | 18.7 - 800 | |

| Expression of BRCA2 | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes (n = 14) | 591.57 ± 298.91 | 675 (548) | 178 - 1000 | |

| No (n = 56) | 48.73 ± 32.68 | 36.4 (26.35) | 18.7 - 158 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; BC, breast cancer.

a Based on Mann-Whitney.

| Stage of BC | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Range | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +1 (n = 22) | 45.65 ± 42.89 | 34 (16) | 18.7 - 213 | < 0.001 |

| +2 (n = 36) | 133.57 ± 207.51 | 40.3 (48.05) | 24.7 - 800 | |

| +3 , +4 (n = 12) | 458.20 ± 410.39 | 150 (707.2) | 68 - 1000 |

Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; IQR, interquartile range.

a According to Kruskal-Wallis.

5. Discussion

Breast cancer is a prevalent malignancy worldwide, with biomarkers playing a crucial role in its management. BRCA1/2 mutations are important for risk assessment in high-risk families (21). Studies have shown that BRCA1 gene expression and CA15-3 levels increase significantly with advanced cancer stages, suggesting their potential utility in prognosis and disease monitoring (14). The CA15-3, along with CEA and CA27-29, has demonstrated value in early diagnosis of metastasis and treatment monitoring (22). Emerging biomarkers like circulating tumor cells and tumor-derived DNA show promise for future applications (21). Overall, biomarkers assist in risk assessment, diagnosis, prognosis, treatment efficacy prediction, and disease surveillance in BC management (23). Assessing BRCA2 levels is crucial for risk assessment, prognosis, and treatment planning, especially in cases with a family history of BC (24).

In our study, 20% of patients showed positive BRCA2 gene expression, with a mean CA15-3 level of 157.30 ± 255.96. Li et al. (25) reported 81% BRCA2 expression, while Guzman-Arocho et al. found 55.3% in young women with BC (26). Li et al. (27) reported a 54.95% CA15-3 expression rate, contrasting with Zhao et al. (28), who found 5.62% in BC patients.

Various factors, such as age, diet, BMI, reproductive history, oncogenes, breast density, and family history, contribute to BC development (29). Family history, with an odds ratio of 1.71, significantly impacts BC risk, especially for those with two or more relatives affected (30). Our study found a significant association between BRCA2 gene expression and a history of breast and ovarian cancers, emphasizing the importance of family history. Pallonen et al. reported higher BRCA gene expression in individuals with a history of ovarian and BC (31), while Liu et al. highlighted the link between BC rates and family history (32). These findings underscore the crucial role of family history in BC screening and prevention.

We found a statistically significant difference in the mean CA15-3 levels between patients with positive and negative BRCA2 gene expression (P < 0.001). BRCA2 plays a crucial role in DNA repair, ensuring chromosomal stability in BC. Unique clinical traits are associated with BRCA-mutated BCs (33, 34). While clinical significance of BRCA2 is less explored than that of BRCA1, a 2021 study confirmed its elevated expression in BC (35). Our research examined BRCA2 expression across different disease stages. Notably, gene expression significantly increased with advancing stages: +3 (45.45%), +2 (22.22%), and +1 (4.55%). A comparable study by Pessoa-Pereira et al. revealed higher BRCA2 expression in stages 2 and 3 (36).

The CA15-3, a MUC-1 glycoprotein, serves as a widely used tumor marker in BC management (37). Elevated CA15-3 levels can be detected in early stages (38), although it is predominantly associated with metastatic BC (39). High CA15-3 levels are also found in different carcinomas and benign diseases. Nonetheless, the use of CA15-3 in early-stage BC is controversial due to no organ and tumor specificity and sensitivity (40, 41). In our study, the expression of the CA15-3 gene was examined across different BC stages, revealing a significant increase in mean CA15-3 levels with advancing disease stages (highest +3, followed by +2, and lowest +1). Similar findings were reported by Li et al. (27), where CA15-3 expression increased with stage (6.9% in stage 1, 8.8% in stage 2, and 18% in stage 3), and by Araz et al. (42), showing expression rates of 18.73% in stage 1, 16.02% in stage 2, and 19.16% in stage 3 of BC.

5.1. Conclusions

The results of this study highlight the importance of biomarkers in identifying BC patients. However, a limitation of this work is that it did not provide detailed molecular or scientific explanations for the observed correlations between BRCA2 gene expression, CA15-3 levels, and disease progression. Although the study suggests that these biomarkers can aid in early detection and reduce treatment costs, further research is needed to clarify the underlying mechanisms and validate their clinical utility.

5.2. Limitations

One of the main limitations of this study was the relatively small sample size (n = 70), which may limit the statistical power to detect subtle differences or strong associations between BRCA2 gene expression, CA15-3 levels, and BC grades. This constraint affects the generalizability of the findings to broader populations and reduces the ability to draw firm conclusions. Additionally, the lack of a control group and long-term patient follow-up further might limit the depth of analysis.

5.3. Suggestions

Future studies should aim to include larger and more diverse cohorts, incorporate control groups, perform power calculations before sampling, and assess long-term clinical outcomes to validate and expand upon these preliminary findings. To generalize the results of this study, it is necessary to increase the sample size, include a more diverse population, add a control group, collect long-term data, and conduct multicenter studies.