1. Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related death, with approximately 1.9 million new cases and 930 000 deaths in 2020. (1) Incidence and mortality rates vary up to 10-fold globally, with the highest rates in developed countries and rapidly rising trends in low- and middle-income nations (2). Despite the growing incidence, mortality rates have decreased in developed countries due to improved screening and treatment options (3).

The CRC incidence in Iran shows an increasing trend, yet remains below global rates. Earlier data reported age-standardized incidence rates of 8.16 and 6.17 per 100 000 for males and females, respectively, while more recent studies indicate a rate of approximately 15 per 100 000, reflecting the rising burden in recent years (4, 5).

Mutations in KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF genes play a crucial role in CRC and impact treatment decisions, particularly regarding anti-EGFR therapies. The prevalence of these mutations varies across studies and populations, which is important because such differences can influence the effectiveness of targeted therapies and the need for population-specific guidelines. KRAS mutations are the most common, occurring in 35.9 to 42.4% of CRC cases (6, 7). NRAS mutations are less frequent, with rates ranging from 4 to 7.8%. BRAF mutations show the most variability, with reported frequencies between 1.2 and 7.1% (6, 8).

KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutations significantly impact treatment outcomes in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) (9). While survival rates for mCRC have improved overall, patients with these mutations continue to have worse prognoses, highlighting the need for targeted therapies and improved treatment strategies (10, 11).

Despite extensive global research on RAS/BRAF mutations in CRC, their clinical patterns and survival impact in Iranian patients remain underexplored.

2. Objectives

This study examines the clinical characteristics and outcomes in metastatic CRC patients with these mutations.

3. Methods

This retrospective study was conducted on patients with mCRC who underwent RAS/BRAF tissue testing between 2021 and 2023. Data were collected from Imam Hussein Hospital, a major referral center affiliated with Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran.

The inclusion and exclusion process followed CONSORT-style guidelines for transparency and is summarized in the following flow diagram description.

1. Initial screening: 114 patients identified with mCRC and RAS/BRAF testing.

2. Exclusions (n = 40):

- Incomplete or missing clinical/molecular data (n = 21).

- Lost to follow-up or insufficient survival data (n = 9).

- Non-colorectal primary tumors or mixed histologies (n = 6).

- Death due to non-cancer-related causes (n = 4).

3. Final cohort: Seventy-four patients meeting all eligibility criteria (histopathologically confirmed colorectal adenocarcinoma, radiologic/surgical confirmation of metastatic disease, and available RAS/BRAF mutation results).

Clinicopathological features included clinical data (demographics, metastatic patterns, treatment, survival) and pathological data (tumor characteristics, molecular mutations) describing the disease. This study collected the following data.

- Demographics (age, sex).

- Tumor characteristics (location, differentiation, TNM stage/grade).

- Metastatic patterns.

- First-line treatment details [regimen, duration, best response, progression-free survival (PFS)].

- Survival outcomes [last follow-up, overall survival (OS)].

Tumor specimens (primary/metastatic), specifically from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, were used for RAS/BRAF testing. Genomic DNA was isolated from these FFPE samples, and mutations were determined using the MEBGEN RASKET-B kit, which combines multiplex PCR, reverse oligonucleotide sequencing, and xMAP® technology (Luminex®).

Disease assessment was typically conducted at regular intervals of every 2 to 8 weeks using computed tomography (CT). Radiologic response assessments were performed by experienced oncologists according to RECIST 1.1 criteria, with independent review by at least 2 oncologists for confirmation. The OS was calculated from enrollment to death (any cause), with living patients censored at last follow-up. The PFS was defined from enrollment to first progression or death. ORR represented the proportion of patients achieving complete or partial responses among all enrolled cases, as confirmed by CT scans per RECIST 1.1. Patients were followed until death or the data cut-off date in December 2024, whichever occurred first.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.25 (significance threshold: P < 0.05). Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test. Survival outcomes (OS/PFS) were analyzed via the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank testing for group comparisons. Cox proportional hazards regression models — both univariate and multivariate — estimated hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Multivariate models adjusted for key covariates, including age, sex, tumor location, and treatment regimen.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1400.205). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and patient confidentiality was maintained through data anonymization (removal of personal identifiers).

4. Results

This study included 74 patients with mCRC, 51.4% of whom were male. The mean age was 57.7 ± 12.7 years. Based on molecular status, patients were categorized into 4 subgroups: KRAS-mutated (47.3%), wild-type (47.3%), NRAS-mutated (2.7%), and BRAF-mutated (2.7%). No significant associations were observed between mutation subgroup and age (P = 0.697), sex (P = 0.173), or tumor location (P = 0.412). Baseline characteristics stratified by mutation status are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | All | KRAS | NRAS | BRAF | Wild Type | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 12.68 ± 57.65 | 11.74 ± 59.49 | 9.19 ± 57.5 | 25.24 ± 54.0 | 13.38 ± 56.03 | 0.697 |

| Under 65 | 50 (67.6) | 22 (62.9) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 25 (71.4) | 0.608 |

| 65 and above | 24 (32.4) | 13 (17.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 10 (28.6) | 0.608 |

| Gender | 0.173 | |||||

| Male | 38 (51.4) | 15 (42.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 22 (62.9) | |

| Female | 36 (48.6) | 20 (57.1) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 13 (17.6) | |

| Place of the tumor | 0.412 | |||||

| Ascending colon | 16 (21.6) | 12 (34.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (11.4) | |

| Transverse colon | 5 (6.8) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (11.4) | |

| Descending colon | 10 (13.5) | 6 (17.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Sigmoid | 19 (25.7) | 7 (20) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 10 (28.6) | |

| The rectum | 22 (29.7) | 9 (25.7) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 12 (34.3) | |

| Unknown | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.7) | |

| The degree of differentiation | 0.284 | |||||

| Excellent | 25 (34.2) | 12 (35.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 11 (31.4) | |

| Medium | 39 (53.4) | 19 (55.9) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 19 (54.3) | |

| Weak | 9 (12.3) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 5 (14.3) | |

| The number of metastases | 0.156 | |||||

| ≥ 1 | 50 (67.6) | 23 (65.7) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 26 (74.3) | |

| 0 | 24 (32.4) | 12 (34.3) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 9 (25.7) | |

| Liver metastasis | 0.681 | |||||

| Yes | 58 (78.4) | 26 (74.3) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 28 (80) | |

| No | 16 (21.6) | 9 (25.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (20) | |

| Peritoneal metastasis | 0.411 | |||||

| Yes | 28 (37.8) | 16 (45.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 11 (31.4) | |

| No | 46 (62.2) | 19 (54.3) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 24 (68.6) | |

| Lung metastasis | 0.366 | |||||

| Yes | 13 (17.6) | 5 (14.3) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 6 (17.1) | |

| No | 61 (82.4) | 30 (85.7) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 29 (82.9) | |

| Death | 0.715 | |||||

| Yes | 60 (81.1) | 27 (77.1) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 29 (82.9) | |

| No | 14 (18.9) | 8 (22.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (17.1) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

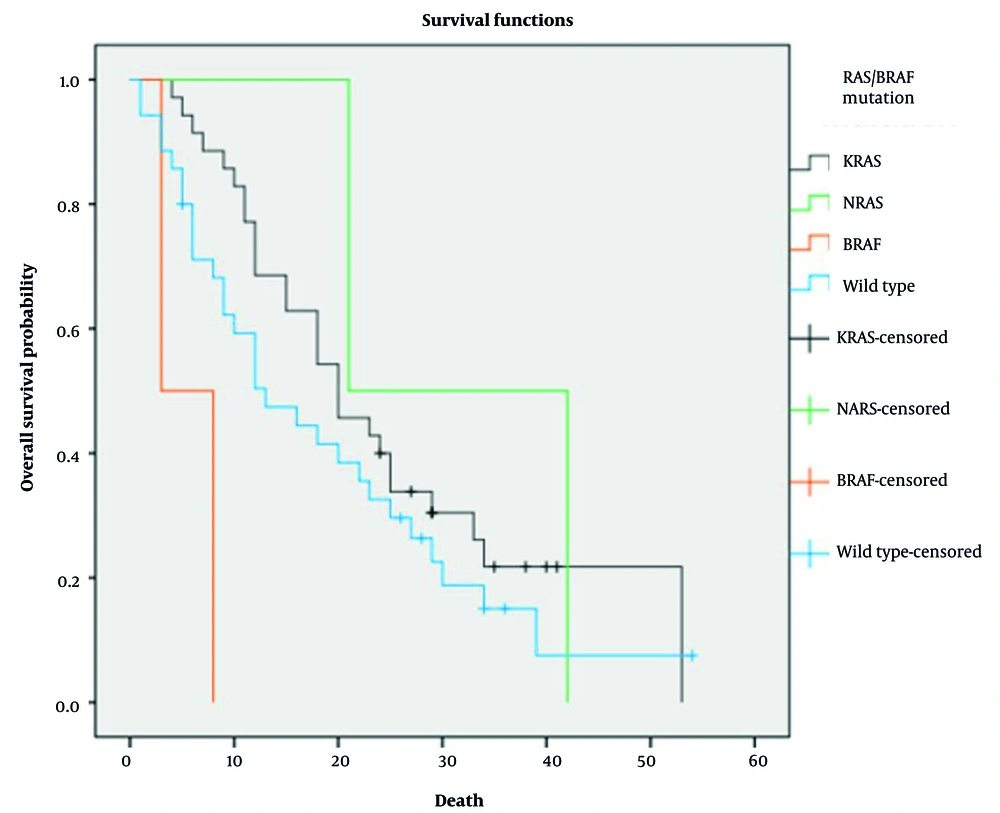

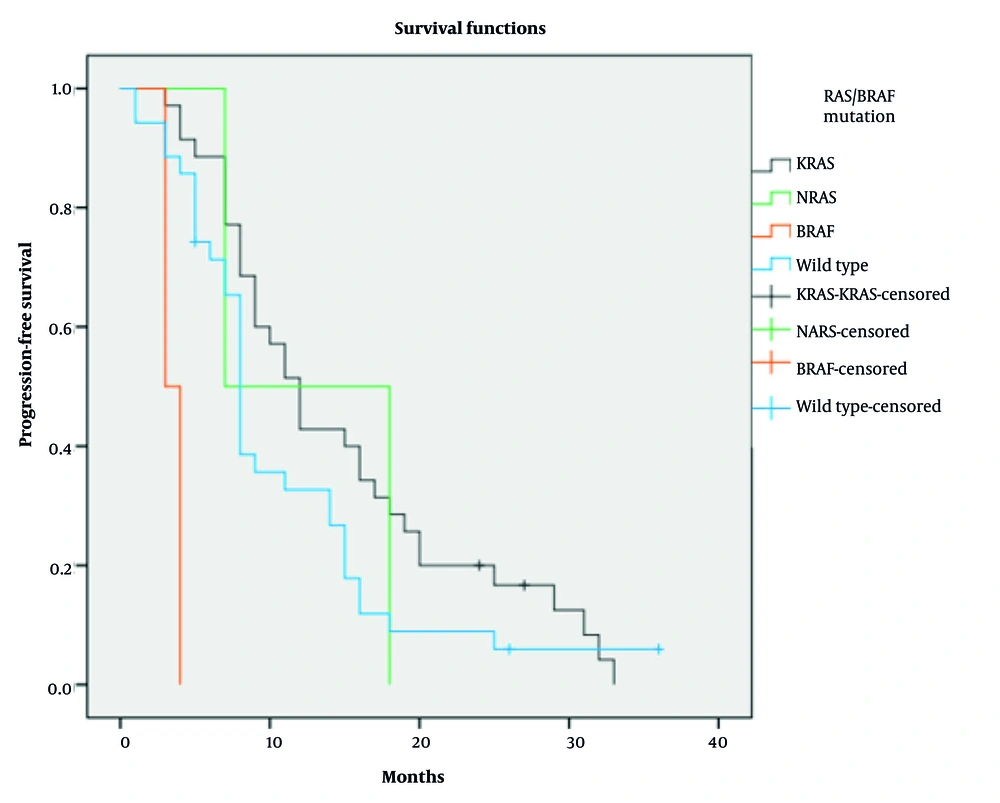

At the time of analysis, 81.1% of patients had died, but mortality rates did not significantly differ among subgroups (P = 0.715). The median OS for the entire cohort was 18 months (95% CI: 12.68 - 23.31 months). Due to small sample sizes (n = 2 each for BRAF and NRAS mutations), these subgroups were excluded from statistical analysis, as their limited numbers prevented reliable survival outcome interpretation. In the remaining subgroups, median OS was 20 months in the KRAS-mutated group and 13 months in the wild-type group (P = 0.234; Figure 1). The median PFS for the entire cohort was 9 months (95% CI: 7.33 - 10.66 months). Median PFS was 12 months in the KRAS-mutated group and 8 months in the wild-type group (P = 0.189; Figure 2).

Median PFS was 12 months in the KRAS-mutated group and 8 months in the wild-type group (P = 0.189; Figure 2). Detailed Cox regression results for OS and PFS by RAS/BRAF V600E status, including HRs and 95% CIs, are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Variables | HR | CI 95% | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| KRAS | Reference | ||

| Wild type | 1.380 | 2.33 - 0.816 | 0.280 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

| Variables | HR | CI 95% | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| KRAS | Reference | ||

| Wild type | 1.499 | 2.455 - 0.915 | 0.108 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

The OS was also analyzed in relation to patient characteristics, including age, gender, number of metastatic sites, and specific metastatic locations (Table 4). Patients aged over 65 years (HR = 1.45, 95% CI: 0.78 - 2.69; P = 0.243), males (HR = 1.32, 95% CI: 0.72 - 2.41; P = 0.367), and those with multiple metastases (HR = 1.67, 95% CI: 0.89 - 3.14; P = 0.112) or liver (HR = 1.28, 95% CI: 0.65 - 2.52; P = 0.468), peritoneal (HR = 1.51, 95% CI: 0.76 - 3.00; P = 0.239), or lung involvement (HR = 1.39, 95% CI: 0.71 - 2.72; P = 0.334) showed higher HRs. None of these associations reached statistical significance.

| Variables | HR | CI 95% | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | |||

| Under 65 | Reference | ||

| 65 and above | 1.367 | 2.334 - 0.801 | 0.252 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.201 | 1.998 - 0.722 | 0.480 |

| The number of metastases | |||

| 1 | Reference | ||

| < 1 | 1.925 | 18.79 - 0.197 | 0.573 |

| Liver metastasis | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.046 | 1.946 - 0.562 | 0.887 |

| Peritoneal metastasis | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.185 | 2.012 - 0.698 | 0.529 |

| Lung metastasis | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.203 | 2.272 - 0.637 | 0.569 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

5. Discussion

This study analyzed clinicopathological characteristics and survival in Iranian mCRC patients with RAS/BRAF mutations. The rectum, sigmoid, and ascending colon were the most common tumor sites, with no significant correlation between tumor location and mutation subgroup (P = 0.412). Most tumors were moderately (53.4%) or well differentiated (34.2%), while poorly differentiated histology was less frequent (12.3%, P = 0.284). The liver was the primary site of metastasis (75.8%), and most patients had a single metastatic site.

KRAS mutations were detected in 47.3% of patients, while NRAS and BRAF mutations each accounted for 2.7%; the remaining 47.3% were RAS/BRAF wild-type. Compared to global data — reporting KRAS in 35.9% to 42.4%, NRAS in 4% to 7.8%, and BRAF in 1.2% to 7.1% of mCRC cases — our cohort demonstrated a higher KRAS and lower NRAS frequency, consistent with the findings of Ikoma et al., Rasmy et al., Ge et al., and Costello et al. (12-15).

Regionally, the KRAS mutation rate in our cohort exceeds the 19.5% reported for Middle Eastern populations (16). Within Iran, previous estimates for KRAS range from 33.6% to 33.9%, NRAS around 5.7%, and BRAF mutations remain rare (0 - 3.2%) (17-19). Our results support the low prevalence of BRAF mutations nationally, while indicating a modestly higher KRAS rate and lower NRAS frequency.

These variations may reflect regional molecular differences or methodological inconsistencies in testing. Broader, multicenter studies are needed to validate these findings and clarify their clinical implications in Iranian mCRC populations.

Although the KRAS-mutated subgroup showed numerically longer median OS (20 months) and PFS (12 months) than the wild-type group (13 months and 8 months, respectively), these differences were not statistically significant. This pattern, which contrasts with findings from larger cohorts, may be attributed to the limited statistical power of our sample.

No significant association was observed between mutation status and primary tumor location (P > 0.05), with rectum (29.7%), sigmoid colon (25.7%), and ascending colon (21.6%) being the most common sites across subgroups. Similarly, mutation status showed no correlation with patient age or gender. While Kafatos et al. reported a balanced gender distribution (20), and Kwak et al. found a higher RAS prevalence in women (21), our findings did not indicate any gender-based differences in KRAS mutation rates.

Most patients (67.6%) presented with a single metastatic site, predominantly the liver (75.8%). NRAS mutations were more frequent in older patients, consistent with prior reports. BRAF mutations were linked to peritoneal spread, while KRAS/RAS mutations were more often associated with lung metastases. Left-sided tumors tended to metastasize to bone and lung, and rectal cancers to the brain, bone, and lung. However, none of these associations reached statistical significance in survival analysis.

The median OS was 18 months (95% CI: 12.68 - 23.31), markedly shorter than the 42.27 months reported by Dolatkhah et al. in another Iranian cohort (5). This difference may reflect variations in patient characteristics, treatments, or institutional practices, highlighting the importance of multicenter data.

The PFS analysis showed a median of 9 months overall. The KRAS-mutated subgroup had the longest median PFS (12 months), followed by the wild-type group (8 months), although these differences were not statistically significant.

These findings contrast with international data, where KRAS mutations are typically linked to poorer outcomes due to limited response to anti-EGFR therapy (13, 14). In our cohort, both OS and PFS were numerically longer in KRAS-mutated patients, though not statistically significant (OS: P = 0.280; PFS: P = 0.108), challenging established prognostic expectations (15).

Although our cohort showed better OS and PFS in KRAS-mutated patients than in wild-type, which contrasts with global data, several factors may explain this discrepancy. Differences in specific KRAS mutation subtypes, treatment regimens including surgical resection of metastatic sites, anti-EGFR therapy use, and patient selection criteria may have contributed to survival benefits in our cohort. The influence of population-specific variables, as well as potential selection bias and inclusion/exclusion criteria, should be considered in interpreting these findings.

Beyond mutation status, we also evaluated clinicopathological variables influencing OS (Table 4). Patients over 65, male sex, multiple metastatic sites, and liver, peritoneal, or lung involvement were associated with higher HR (> 1.0). These trends suggest poorer outcomes and are consistent with established negative prognostic indicators in mCRC. However, none of these associations reached statistical significance, likely due to the limited sample size. In smaller cohorts, clinical variables such as metastatic pattern or tumor location may exert a more noticeable impact than molecular profiles. These findings underscore the need for expanded studies to better define the prognostic relevance of clinical factors in Iranian mCRC patients.

This study has methodological limitations, including a small sample size that reduces statistical power for subgroup analyses, notably survival comparisons, where trends lacked significance. The low frequency of BRAF and NRAS mutations (n = 2 each) limits meaningful subgroup evaluation, increases type II error risk, and restricts definitive prognostic conclusions, consistent with prior studies on rare mutations. The single-center design introduces selection bias, limiting generalizability and risking misleading results for researchers and clinicians. These limitations must be clearly addressed to avoid misinterpretation, and findings interpreted cautiously. Larger, multicenter studies with adequate cohorts are needed to validate these observations and clarify mutation-specific prognostic implications in Iranian mCRC patients.

5.1. Conclusions

The comprehensive analysis of tumor characteristics (location, differentiation, and metastasis) and survival metrics (OS, PFS, and HRs) across mutated subgroups offers critical insights into CRC prognosis. Further research should clarify the mechanisms underlying subgroup outcome disparities to inform the development of personalized therapies.