1. Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a non-enveloped DNA virus primarily transmitted through sexual or skin-to-skin contact (1). More than 200 genotypes have been identified, with high-risk types predominantly transmitted through sexual contact (2). Persistent HPV infection is a known carcinogenic factor (3). In the United States, approximately 48,000 new HPV-related cancer cases are reported annually, with around 37,800 directly attributable to HPV (4).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 291 million women worldwide are infected with HPV, and 32% of these cases involve high-risk genotypes, while not all infections inevitably lead to cervical cancer (5). In Iran, the prevalence of HPV among healthy women is around 7%, whereas it increases to about 76% in women with cervical cancer (6). A meta-analysis by Malary et al. reported an overall HPV prevalence of 9.4%, with genotypes 16 and 18 being the most common high-risk types associated with cervical cancer (7).

The HPV is the primary initiating factor in cervical cancer (8, 9), the fourth most common cancer in women globally, after breast, colorectal, and lung cancers. In 2020, approximately 600,000 new cases with cervical cancer and 340,000 related deaths were reported (2), with 85% of these deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries. However, in Iran, cervical cancer ranks 11th among all cancers, and the average age of patients is about 10 years higher than in western countries (10). According to WHO projections, mortality in these regions is expected to increase by 27% by 2030, in contrast to a projected 1% increase in high-income countries (11).

Cervical cancer is highly preventable through vaccination, regular screening, and timely diagnosis (12, 13). However, previous studies indicated a lack of public awareness and knowledge about this disease, even among highly educated women. This knowledge gap leads to reduced vaccine uptake, delayed diagnosis, and increased mortality (14-18). In traditional and religious societies such as Iran, HPV infection is also considered taboo and stigmatized due to its nature as a sexually transmitted infection, leading to fear, shame, and reluctance to seek care (19, 20). This stigma can negatively impact follow-up and treatment, highlighting the need for effective educational interventions (18).

Traditional educational methods are resource-intensive and may lack scalability (21). Advances in telehealth technology, especially mobile health (mHealth) tools, offer a promising solution due to their effectiveness (22, 23), feasibility, user acceptability (24, 25), and cost-efficiency (26). Previous studies, including trials conducted in Argentina and South India, demonstrated that mHealth tools can improve knowledge and increase Pap smear uptake (27, 28). However, their intervention was limited either to sending text messages or to apps whose educational content was not grounded in a specific theoretical model. Although studies based on the health belief model (HBM) have been conducted in Iran, they have primarily employed conventional educational methods (21) rather than electronic or mobile platforms. Due to this gap, we developed a mHealth application based on the HBM, one of the successful models for motivating people toward preventive programs (29, 30), to improve women’s knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors related to HPV and cervical cancer screening (31, 32).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to design, develop, and evaluate a mobile application intended to enhance knowledge about HPV and cervical cancer, while also encouraging women of reproductive age to participate in cervical cancer screening.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

A mixed-methods study was conducted, combining the design and development of a mobile application with a single-blind randomized clinical trial to evaluate its effectiveness. As the nature of the intervention (mobile app), blinding of participants and researchers was not feasible. However, the data analyst was blinded.

3.2. Study Participants and Sampling

One healthcare center was randomly selected from each of Ardabil's five districts. Considering a 10% attrition rate, 380 sexually active women aged 15 to 45 were enrolled (76 per center). Participants had no prior history of HPV infection, cervical cancer, or HPV vaccination, and were smartphone-literate. The sample size was calculated based on an expected increase in Pap smear uptake rates from 28% (33) to 50% (Cohen's h = 0.46) (34), with 80% power, 5% alpha, and 10% dropout, resulting in 380 participants (190 per group) (35). Recruitment was conducted over a 3-month period:

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Women aged 15 - 45, sexually active, literate, and able to use a smartphone were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were participants who withdrew or expressed unwillingness to continue at any stage.

3.4. Data Collection Tool and Technique

Validated questionnaires were used to assess HPV knowledge and HBM-based screening behaviors. The HPV Knowledge Questionnaire (10 items) was adapted from Guvenc et al. (36) and the HBM-Based Screening Behaviors Questionnaire (26 items) was adapted from Khani Jeihooni et al. (37). Both were translated into Persian using the forward-backward method by two experts in reproductive health and health education with proven English language proficiency and validated by ten experts (content and face validity). After removing two questions [Content Validity Index (CVI) < 0.79 or CVR < 0.62] and revising for clarity and appearance, CVIs were 0.94 (knowledge) and 0.93 (HBM), and Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega showed high internal consistency (0.94 and 0.91, respectively).

HBM construct scores were interpreted based on percentage cutoffs: Low (< 50%), moderate (50 - 74%), and high (≥ 75%) (38).

3.5. Intervention

3.5.1. Design of the Mobile Application: Human Papillomavirus-Bye

The "HPV-Bye" mobile app was developed for Android systems, using a user-centered design and based on the HBM. It includes 18 interactive screens with modules on HPV, cervical cancer, and the importance of Pap smear testing. Content was informed by WHO (39, 40), CDC guidelines (41) and previous comprehensive literature reviews (42) and validated by 15 users (CVI = 0.88) and 15 experts (CVI = 0.87, acceptable if CVI ≥ 0.73) (43). The design was grounded in the HBM, incorporating constructs such as perceived susceptibility to HPV, perceived severity of its complications, perceived benefits of screening, perceived barriers, cues to action, and strategies for behavioral empowerment (29). This model is widely regarded as an effective theoretical framework in promoting preventive health behaviors (44, 45).

To facilitate user engagement and comprehension, the content is presented in a question-and-answer format using clear and accessible language tailored to the target population. Upon completing initial data entry forms and questionnaires, users are guided through the educational modules. After reviewing the content, they are invited to decide on Pap smear testing. If they choose to undergo the test, they may upload the results directly within the app. If not, they are asked to indicate their reason from a predefined list. The application’s name, HPV-Bye, was selected based on feedback from both app users and expert reviewers, chosen from several options proposed by the research team.

3.5.2. Application Validation

To assess the preliminary version of the HPV-Bye mobile application, a two-phase validation process was conducted involving both app users and healthcare professionals, and necessary modifications were made wherever required.

3.5.3. User Validation

User feedback was collected using the Telehealth Usability Questionnaire (TUQ), a standardized tool developed and validated by Parmanto et al. and their feedback for assessing the usability of telehealth educational tools. The TUQ comprises 21 items across six domains: Usefulness (3 items), ease of use and learnability (3 items), interface quality (4 items), interaction quality (4 items), reliability (3 items), and satisfaction and future use (4 items) (46). Responses were obtained using a four-point Likert scale. The questionnaire was adapted through the standard forward-backward translation procedure (47), as detailed previously. The finalized questionnaire and the mobile application were subsequently administered to 15 women, selected according to the criteria described in the “Study Participants” section. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel. The overall CVI of the application was calculated as 0.88, indicating an acceptable level of content and face validity from the users’ perspective (43).

3.5.4. Expert Validation

For expert validation, a Separate Standard Questionnaire designed by Maciel et al. was employed. This tool was specifically developed to assess the content and face validity of mobile applications related to the prevention of sexually transmitted infections. It also underwent the forward-backward translation process to ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence, as described previously. 15 experts in reproductive health and gynecology with prior experience in sexual health and STIs were selected. They completed the questionnaire, which contains 21 items divided into the following domains: Objectives and content (6 items), structure and functionality (11 items), and communication (4 items) (28). Responses were recorded using a four-point Likert scale. The overall CVI from expert evaluation was 0.87, indicating a satisfactory level of content and face validity from a professional standpoint. To assess the reliability of the instruments used, Cronbach’s alpha (48) and McDonald’s omega coefficients (49) were calculated, with values of 0.94 and 0.91, respectively (acceptable if α and ω ≥ 0.7). These results indicate excellent internal consistency.

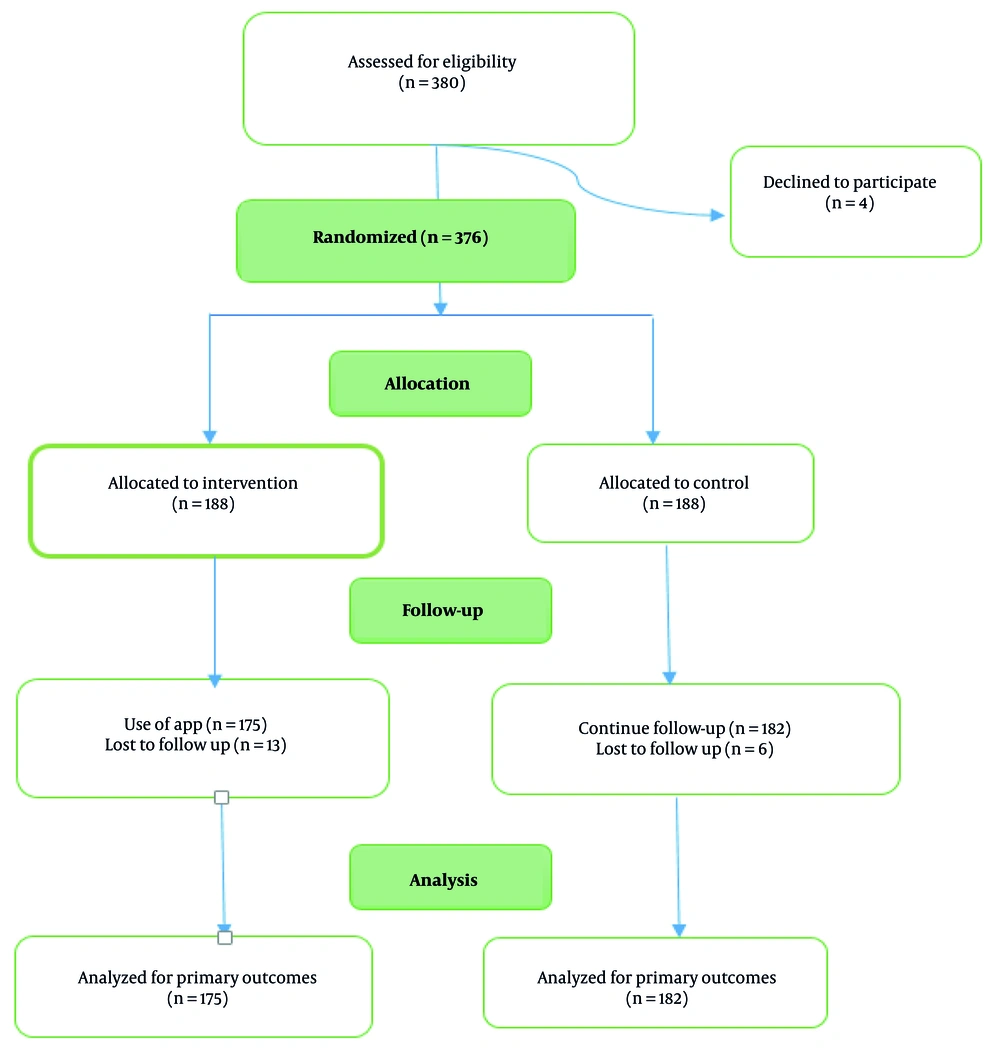

3.6. Procedure

Following the development and validation of the HPV-Bye mobile application, the intervention phase of the study was carried out as a single-blind randomized clinical trial. Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention (user) or control group in 1:1 ratio after providing written informed consent. While the control group continued to receive routine care from health centers, the intervention group was provided access to the final version of the HPV-Bye mobile application (Figure 1). To support user access, an audio guide was included, and for participants unable to install the app on their smartphones, a web-based version of HPV-Bye was made available.

All participants completed the validated questionnaires assessing HPV-related knowledge and HBM-based screening behaviors at three time points: Baseline, immediately post-intervention, and eight weeks later. Data were analyzed to assess the effect of the intervention on knowledge improvement and behavioral intention regarding cervical cancer screening.

3.7. Outcome Measures

Both groups completed assessments at baseline, immediately after the intervention, and eight weeks post-intervention. Outcomes included changes in knowledge, HBM constructs, and Pap smear uptake, with results uploaded to the app.

3.8. Ethical Consideration

The study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1401.194) and RCT (IRCT20230125057224N1). Written informed consent was obtained, and participant confidentiality was maintained. Application launch and questionnaire usage were licensed by the ministry of culture and original developers. After the study, the control group was granted access to the app.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

Baseline differences were assessed using chi-square tests. Changes in knowledge and HBM constructs over time were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA). Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied if Mauchly’s test indicated a violation of sphericity (50, 51). Analyses were performed using SPSS v26, with significance set at P < 0.05. The app required full completion of each questionnaire to continue; therefore, participants with incomplete data (n = 23) who discontinue the study were excluded from the analysis.

4. Results

Of the 380 women who initially enrolled in the study, 23 participants were excluded (4 declined to participate and 19 were lost to follow-up), as a result, 357 of them were included in the final analysis. The mean ± SD age of the participating women was 30.59 ± 5.63 years. Most of them (65.5%) were housekeeper, approximately half (54.6%) held a university degree, and 30% had no history of childbirth. According to Table 1, there were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in terms of baseline characteristics such as age, educational level, occupation, and known risk factors for cervical cancer such as early sexual intercourse (< 18 years), parity, recurrent vaginal infections, consistent condom use, and family history of cervical cancer. Also, there were not significant differences between two groups in knowledge and HBM constructs before intervention (Table 2). Table 2 shows that participants in the intervention group exhibited a significant and meaningful increase in their knowledge immediately compared to the control group (P = 0.001). While a modest reduction in knowledge was noted at the 8-week follow-up, this did not substantially diminish the overall gains achieved immediately after the intervention. More importantly, the user group showed significant improvements in knowledge (MD: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.41 to 1.17), perceived susceptibility (MD: 4.17; 95% CI: 3.26 to 5.08), severity (MD: 4.03; 95% CI: 3.13 to 4.93), and benefits (MD: 3.46; 95% CI: 2.59 to 4.33; all P < 0.001), along with a reduction in perceived barriers (MD: -4.60; 95% CI: -5.53 to -3.67) compared with control group (all P < 0.001). Additionally, there was a noteworthy increase in both perceived cues to action (MD: 2.35; 95% CI: 1.62 to 3.08) and self-efficacy (MD: 2.66; 95% CI: 1.92 to 3.40), further demonstrating the positive impact of the intervention (P < 0.001).

| Variables | Intervention Group (N = 175) | Control Group (N = 182) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 0.42 | ||

| 24 - 15 | 25 (14.3) | 23 (12.6) | |

| 25 - 35 | 111 (63.4) | 127 (53.4) | |

| 36 - 45 | 39 (22.3) | 32 (17.6) | |

| Education | 0.26 | ||

| ≤ Diploma | 72 (41.1) | 90 (49.5) | |

| Bachelor's degree | 84 (48) | 76 (41.8) | |

| ≥ Master's degree | 19 (10.9) | 16 (8.8) | |

| Occupation | 0.16 | ||

| Housekeeper | 110 (62.9) | 124 (68.1) | |

| Employee | 30 (17.1) | 18 (9.9) | |

| Teacher | 19 (10.9) | 17 (9.3) | |

| Health care provider | 16 (9.1) | 23 (12.6) | |

| Family history of cervical cancer | 0.81 | ||

| Yes | 166 (94.9) | 171 (94) | |

| No | 9 (5.1) | 11 (6) | |

| Early sexual intercourse | 0.16 | ||

| Yes | 46 (26.3) | 37 (20.3) | |

| No | 129 (73.7) | 145 (79.7) | |

| Recurrent vaginal infection | 0.16 | ||

| Yes | 34 (19.4) | 47 (25.8) | |

| No | 141 (80.6) | 135 (74.2) | |

| Parity | 0.13 | ||

| Yes | 59 (33.7) | 48 (26.4) | |

| No | 116 (66.3) | 134 (73.6) | |

| Consistent condom use | 0.11 | ||

| Yes | 29 (16.5) | 21 (11.5) | |

| No | 146 (83.4) | 161 (88.5) | |

| History of regular Pap smear test | 0.58 | ||

| Yes | 18 (10.3) | 15 (8.2) | |

| No | 157 (89.7) | 167 (91.8) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

| Variables | Before Intervention | Immediately After Intervention | 8 weeks After Intervention | F (Time × Group) | P-Value for Interaction | Partial Eta Squared (η2p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge (0 - 10) | 196.81 | 0.001 | 0.34 | |||

| Experimental | 4.97 ± 1.45 | 7.94 ± 1.31 | 6.80 ± 1.46 | |||

| Control | 5.07 ± 1.28 | 5.06 ± 1.22 | 6.02 ± 1.18 | |||

| P-value | 0.49 | 0.001 | 0.001 | - | - | - |

| Perceived susceptibility (0 - 25) | 339.25 | 0.001 | 0.36 | |||

| Experimental | 10.90 ± 2.19 | 15.34 ± 2.11 | 15.14 ± 2.22 | |||

| Control | 10.58 ± 2.16 | 10.94 ± 2.23 | 10.92 ± 2.23 | |||

| P-value | 0.16 | 0.001 | 0.001 | - | - | - |

| Perceived severity (0 - 25) | 227.16 | 0.001 | 0.37 | |||

| Experimental | 17.33 ± 1.83 | 21.91 ± 2.14 | 21.76 ± 2.27 | |||

| Control | 17.08 ± 2.08 | 17.77 ± 2.22 | 17.73 ± 2.33 | |||

| P-value | 0.23 | 0.001 | 0.001 | - | - | - |

| Perceived benefit (0 - 25) | 118.54 | 0.001 | 0.25 | |||

| Experimental | 17.44 ± 2.75 | 21 ± 2.29 | 20.91 ± 2.29 | |||

| Control | 17.03 ± 2.75 | 17.54 ± 2.23 | 17.45 ± 2.31 | |||

| P-value | 0.16 | 0.001 | 0.001 | - | - | - |

| Perceived barrier (0 - 25) | 426.66 | 0.001 | 0.46 | |||

| Experimental | 14.69 ± 1.86 | 9.60 ± 1.72 | 9.73 ± 1.83 | |||

| Control | 14.35 ± 2.30 | 14.24 ± 1.86 | 14.43 ± 1.91 | |||

| P-value | 0.12 | 0.001 | 0.001 | - | - | - |

| Cue to action (0 - 10) | 88.28 | 0.001 | 0.31 | |||

| Experimental | 4.74 ± 1.83 | 8.24 ± 1.53 | 7.97 ± 1.62 | |||

| Control | 4.92 ± 1.91 | 5.70 ± 1.48 | 5.62 ± 1.43 | |||

| P-value | 0.35 | 0.001 | 0.001 | - | - | - |

| Perceived self-efficiency (0 - 10) | 118.79 | 0.001 | 0.43 | |||

| Experimental | 4.77 ± 1.80 | 8.35 ± 1.49 | 8.09 ± 1.59 | |||

| Control | 4.59 ± 1.77 | 5.51 ± 1.44 | 5.43 ± 1.49 | |||

| P-value | 0.34 | 0.001 | 0.001 | - | - | - |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Statistical analysis was performed using repeat measures ANOVA to assess time, group, and group × time interaction effects.

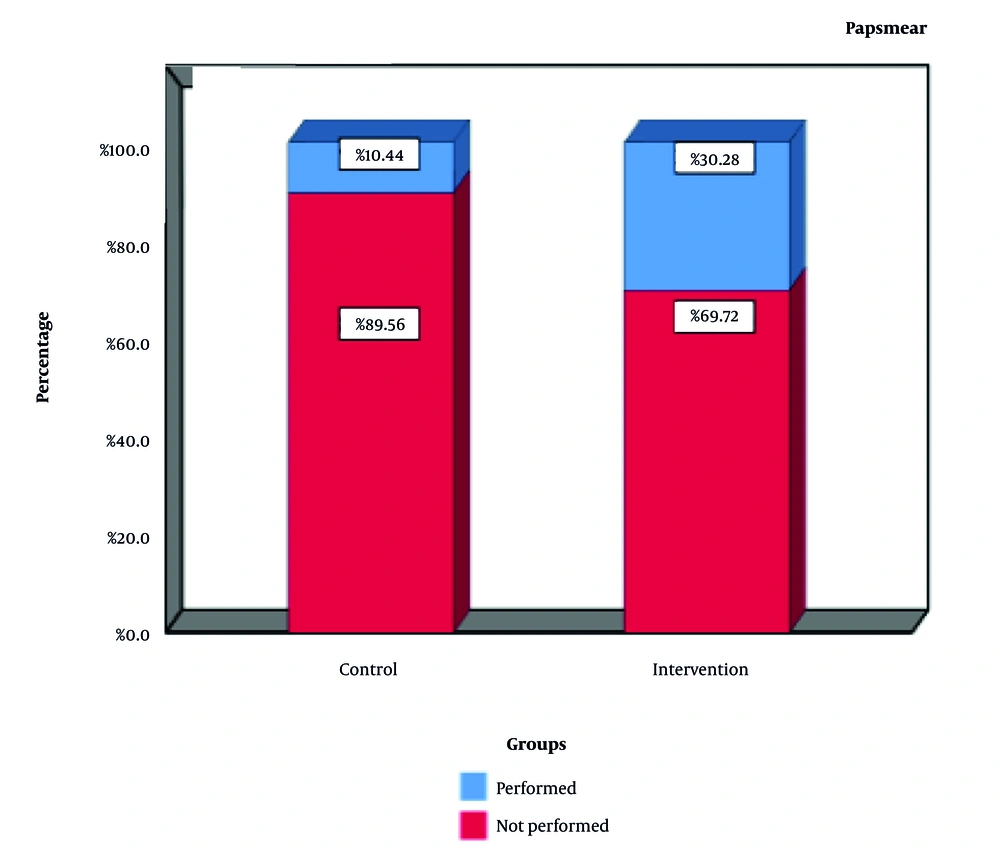

Although significant within-group changes were observed in both the intervention and the control group, the time-by-group interaction was statistically significant (P < 0.05), indicating a significantly greater improvement in the intervention group over the study period. Pap smear uptake increased to 30.28% in the intervention group, compared to 10.44% in the control group (P = 0.001), confirming the effectiveness of the mobile application in encouraging screening behavior (Figure 2).

5. Discussion

Cervical cancer is a preventable disease (13), primarily because of the slow progression of precancerous cervical lesions to invasive cancer (52). Therefore, timely screening and early detection play a critical role in reducing mortality (52, 53). The present study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a mobile application-based educational intervention in enhancing women’s knowledge and awareness of HPV, the primary etiological factor of cervical cancer (3, 4), and in promoting Pap smear uptake, which remains a cornerstone of cervical cancer screening (47, 54).

The study was conducted among 375 sexually active women with no history of HPV infection or vaccination. Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (app users) or the control group. The groups were comparable at baseline in terms of demographic and behavioral variables, including age, education, occupation (55), and risk factors such as early sexual activity (56), parity (57), recurrent vaginal infections (58), condom use (59), and family history of cervical cancer (60).

The evaluation was based on the HBM, a widely recognized framework for predicting health-related behaviors (29), particularly in preventive measures related to HPV (44, 52, 61). Both groups were assessed for baseline HBM constructs: Perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy (62). No significant differences were observed between groups before the intervention.

The intervention group not only demonstrated significant improvements in knowledge but also showed positive changes across key HBM constructs, including perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, self-efficacy, and cues to action. Importantly, perceived barriers decreased significantly, suggesting that the mobile application-based educational program was effective in addressing both cognitive and motivational determinants of cervical cancer screening behaviors. These findings support existing evidence that educational interventions, including those delivered via digital platforms, can be effective in improving health knowledge and behavior (12, 25).

For example, Hombaiah et al. reported similar improvements among socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescent girls in India following an app-based educational intervention (27). Likewise, Sanchez Antelo et al. showed that mobile applications could reduce anxiety and increase knowledge among HPV-positive women (18). Recent studies have reaffirmed the impact of digital interventions on HPV-related behaviors. For instance, a cluster randomized controlled trial in China involving 2552 women through an AI-powered WeChat chatbot showed significant increases in HPV vaccination uptake (P < 0.001) (63). Similarly, a mixed-methods trial of the HPVCF mobile application in Vietnam reported improvements in both vaccination intention and cervical cancer screening participation among women (64).

While social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook have been explored for public health promotion, the evidence for their impact on behavior change is still limited (65). In contrast, mHealth tools, especially mobile apps with user-centered design, demonstrate a more consistent and measurable impact on behavior, as supported by our findings and other recent studies (66, 67).

Our results further showed significant increases in perceived susceptibility and severity in the intervention group, as shown in Table 2. This is consistent with the findings of Wang et al., who demonstrated that perceived susceptibility can act as a powerful motivator for behavior change (68). A study on 1,850 Chinese mothers of adolescent daughters found that a lack of knowledge and low perceived susceptibility were major barriers to HPV vaccine uptake. Many mothers believed their daughters were too young to be at risk of HPV infection or cervical cancer.

Although knowledge and HBM improvements were still evident at the eight-week follow-up, a slight decline was observed, highlighting the need for reinforcement. This is consistent with studies showing that knowledge and behavior tend to diminish over time without continued engagement (69). Incorporating reminders or refresher content within the app could sustain the gains over the long term (70, 71).

Similar to finding in recent studies (72), the significant time by group interaction indicated that the mobile-based educational intervention resulted in greater improvement over time compared to routine care. The large effect sizes observed likely stem from the intervention’s interactive design, the well-educated sample, and the sensitive topic of cervical cancer, which enhanced participant engagement and learning. Caution is warranted when generalizing these findings to broader populations. Improvements in the control group may reflect repeated assessments or minimal effects of standard care (73) or minimal effects of standard care.

Mobile apps like HPV-Bye show strong potential for advancing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) (74). However, a global barrier remains: Many healthcare providers and users lack training on how to integrate SRH apps into practice (74). This study addressed that challenge by including an audio-based guide for installation and use.

Logie et al. found that users value SRH apps for their privacy, accessibility, and ability to empower underserved populations (74). This highlights the opportunity to further engage both providers and users in effective use of mHealth tools — especially in low- and middle-income countries, where the need is greatest (75).

5.1. Conclusions

This study highlights the potential of mHealth applications to promote preventive health behaviors among women, particularly in resource-limited settings where access to care is constrained and stigma surrounding sexually transmitted infections remains high. The mHealth tools like HPV-Bye offer a safe, accessible, and cost-effective platform for health education and behavior change. The significant increase in Pap smear testing observed in the intervention group underscores the practical impact of such technologies in raising awareness and empowering women to take preventive action. Grounded in behavioral theory and developed using a user-centered approach, mHealth interventions can move beyond information dissemination to become effective tools for long-term behavioral change. Leveraging these technologies presents a valuable opportunity to strengthen public health programs and increase participation in preventive care initiatives.

5.2. Limitations

While the intervention demonstrated effectiveness, certain limitations should be acknowledged. The app was developed exclusively for women, although men also play a critical role in HPV prevention. Moreover, the study relied on self-reported data, which may introduce bias. Incorporating verified clinical outcomes and extending the follow-up period could strengthen the validity of findings.

5.3. Recommendations

A unique feature of the app is its integrated audio installation guide, which facilitates accessibility for users with limited literacy. The study findings are primarily generalizable to urban Iranian women aged 15 to 45. The intervention demonstrated a significant impact on HPV knowledge and screening behaviors. To maintain long-term engagement, the use of periodic reminders and content updates is recommended. Although cervical cancer is not among the top ten most prevalent cancers in Iran despite western countries, it is essential that prevention strategies consider local conditions and the role of men.