1. Background

The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that the mortality rate attributed to occupational cancer worldwide is approximately twice as high as that resulting from occupational accidents. One of the occupational factors contributing to cancer is ionizing radiation (IR) (1). In 2008, the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) reported that three categories of medical activities, including diagnostic radiology, nuclear medicine, and radiotherapy, are exposed to IR (2). In the United States, the use of radiological and nuclear medicine methods has increased almost 10-fold and 2.5-fold, respectively, from 1980 to 2006 (3). Healthcare personnel are among the professions exposed to chronic low doses of IR (4, 5).

Many countries have adopted recommendations from the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) based on limiting the occupational effective dose to 20 mSv per year, with a maximum of 50 mSv per year (4). Recommendations include using lead aprons, glasses, and shields, consistently wearing personal radiation monitoring badges, and maintaining proper distance from patients. Through the adoption of these measures and staff training, medical workers have experienced a decrease in radiation exposure over time, despite an increase in the number of procedures performed. A study shows that a significant fraction of medical workers use radiation protection measures inconsistently, including wearing personal dosimeters, which might lead to underestimation of occupational exposures (6). Continued exposure to IR carries the potential for notable adverse health outcomes, encompassing heightened cancer risk alongside genetic and immunological impairments (4). The U.S. Radiologic Technologists (USRT) study observed an increased risk of leukemia, skin cancer, and breast cancer among radiologic technologists who were exposed to chronic low doses of radiation (7). A study highlighted an increased incidence of brain tumors among interventional cardiologists compared to the general population, attributed to higher doses of radiation to the head during procedures (8).

The primary target of IR is the DNA molecule. Ionizing radiation can directly affect DNA by causing structural damage to its molecules. This damage includes breaking the chemical bonds within the DNA strands or causing alterations in the DNA sequence. These changes can lead to mutations, chromosomal abnormalities, or breaks in the DNA strands, genome instability, which can interfere with the cell’s ability to replicate and repair itself properly (9, 10). Genetic instability, characterized by significant alterations in genomes, is a major cause of cancer. Research shows that most cancers exhibit these genetic changes (11).

Micronuclei (MN) assay is a highly effective and rapid technique for assessing DNA damage. A micronucleus is defined as a small chromatin structure visible in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. During mitosis, a nuclear envelope can form around lost chromosomes, creating a structure that resembles a small nucleus (12). A review paper aims to pinpoint the genotoxicity biomarkers that exhibit the highest elevation in individuals exposed to IR (13). Through the search procedure, 65 studies were identified. Significant differences were observed in chromosome aberrations and MN between IR-exposed and unexposed workers (13). Typically, for assessing DNA damage resulting from chronic occupational exposure to IR in hospital staff, peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) are used (14-17). In another review, 19 studies were chosen based on their assessment of MN in both buccal mucosal cells and PBL (18). The findings revealed a high correlation in the MN frequency between these two tissues (18). The buccal MN assay encompasses several key aspects: The biology of the buccal mucosa, its application in human studies investigating DNA damage from environmental exposure to genotoxins, the relationship between buccal MN and cancer, as well as various reproductive, metabolic, immunological, neurodegenerative, and other age-related diseases, and the influence of nutrition and lifestyle (19). Oral mucosal epithelial cells, as the first barrier to genotoxic agents, are easily and quickly sampled, requiring no preparation, culture, and have a limited DNA repair capacity than PBL (20, 21).

2. Objectives

Healthcare personnel are chronically exposed to IR, and a significant fraction of them use radiation protection measures inconsistently. The present study aims at investigating MN as a cost-effective and reliable biomarker for early detection of genomic damage in different wards (endoscopy, radiology, operating room, and angiography). In only two studies, oral mucosal cells from individuals exposed to low and chronic doses of IR have been examined to measure MN, being these papers only focused on the radiology ward (22, 23).

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2023 on 70 employees of one of the medical educational hospitals. The participants included 35 individuals exposed to IR (exposed group) and 35 individuals not exposed to IR who met the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were being employed in the past 6 months, age between 18 and 60 years, and having no history of cancer and radiotherapy, acute infectious diseases (such as influenza) at the time of sampling, or undergoing radiography in the six months before sampling. The exposed group included personnel from departments where routine exposure to IR is common, such as radiology, endoscopy, operating room, and angiography. These departments were chosen to reflect the range of occupational exposure present in the hospital setting and to increase the generalizability of the findings. The control group was selected from administrative and clerical hospital employees using convenience sampling, based on availability and willingness to participate. These individuals had no known occupational exposure to IR.

Demographic information (age, gender, marital status) and occupational details (department, work history), smoking status, alcohol consumption, mouthwash use, drug use, and medical history were obtained through a questionnaire. According to institutional radiation safety records based on film badge dosimetry from the past 5 years, the average occupational exposure levels in the relevant departments have generally remained below 20 mSv per year. However, individual dose records were not available for the study participants. At the beginning of the study, the participants were informed about the study’s objectives and sampling methods, and their informed consent was obtained. This study has been approved by the ethics committee of the university under the number IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1401.077.

3.2. Micronuclei Assay

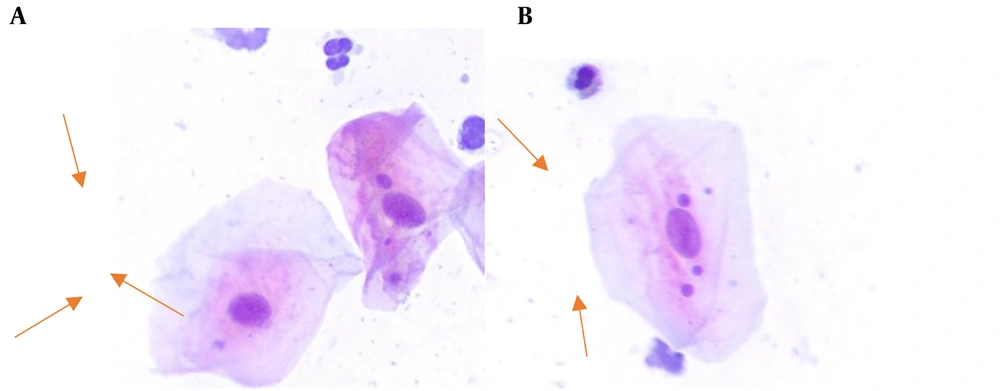

Participants were requested to rinse their mouths with plain water to avoid the staining of mucoid saliva and residual food particles during the staining of slides. Subsequently, using a tongue depressor, exfoliated cells from the buccal mucosa adjacent to the posterior maxillary molars on both sides were gently collected 2 to 3 times. The respective tongue depressor was then spread on a dry and clean slide that had been previously numbered. Immediately, the cells present on the surface were fixed using a cytology fixative spray (Namiracyte) from Bahar Afshan, an Iranian company. The slides were stained using the Papanicolaou method and examined by two pathologists using a Nikon BX50 light microscope at 400x magnification. In each sample, 1000 exfoliated oral epithelial cells were counted to determine the frequency of micronucleated cells. Micronucleus counting involved assessing cells with defined borders and intact nuclei, ensuring they were not overlapping with other cells. Cells that were dead, degenerated, or contained nuclear bubbles were excluded from the count. The criteria determined by Tolbert et al. include criteria for selecting cells and for identifying cells (24).

Figure 1 shows the MN in the exfoliated buccal epithelial cells in exposed and unexposed individuals.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the study groups, indicating that the exposed and unexposed groups are matched.

| Variables | Exposed Group | Non-exposed Group |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 17 (48.6) | 20 (57.1) |

| Female | 18 (51.4) | 15 (42.9) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 9 (25.7) | 8 (22.9) |

| Married | 26 (74.3) | 27 (77.1) |

| Ward | ||

| Radiology | 12 (34.3) | - |

| Angiography | 9 (25.7) | - |

| Endoscopy | 6 (17.1) | - |

| Operating room | 8 (22.9) | - |

| Smoking | ||

| No | 28 (80) | 29 (82.9) |

| Yes | 7 (20) | 6 (17.1) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| No | 33 (94.3) | 35 (100) |

| Yes | 2 (5.7) | 0 |

| Mouthwash use | ||

| No | 32 (91.4) | 32 (91.4) |

| Yes | 3 (8.6) | 3 (8.6) |

| Medical history | ||

| No | 29 (82.9) | 29 (82.9) |

| Yes | 6 (17.1) | 6 (17.1) |

| Drug use | ||

| No | 31 (88.6) | 31 (88.6) |

| Yes | 4 (11.4) | 4 (11.4) |

| Age (y) | 38.25 ± 7.8 | 37.54 ± 8.7 |

| Work experience (y) | 13.62 ± 7.9 | 11.42 ± 10.0 |

The mean frequency of MN in the exposed group (10.97 ± 8.2) was significantly higher than in the non-exposed group (4.02 ± 3.6) (P < 0.05). Additionally, among the factors that may influence the MN frequency, a statistically significant relationship was found with a history of underlying disease, cigarette smoking, and alcohol consumption (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Also, no significant relationship was found between age and work experience with the frequency of MN (P < 0.05).

| Variables | Exposed Group | Non-exposed Group | Total Participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposurehistory | |||

| No | - | - | 4.02 ± 3.6 |

| Yes | - | - | 10.97 ± 8.2 |

| P-value | - | - | 0.000 |

| Maritalstatus | |||

| Single | 12.44 ± 7.5 | 2.62 ± 2.5 | 7.82 ± 7.5 |

| Married | 11.46 ± 8.5 | 4.44 ± 3.8 | 7.39 ± 7.1 |

| P-value | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.83 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 11.29 ± 7.8 | 4 ± 3.7 | 7.35 ± 6.95 |

| Female | 11.66 ± 8.7 | 4.06 ± 3.7 | 7.66 ± 7.6 |

| P-value | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.85 |

| Smoking | |||

| No | 8.86 ± 1.6 | 3.31 ± 3.4 | 7.10 ± 7.6 |

| Yes | 5.34 ± 2.0 | 7.5 ± 2.7 | 9.23 ± 4.4 |

| P-value | 0.92 | 0.009 | 0.34 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| No | 10.27 ± 7.7 | 4.02 ± 3.6 | 7.05 ± 6.7 |

| Yes | 22.5 ± 10.6 | - | 22.5 ± 10.6 |

| P-value | 0.039 | - | 0.002 |

| Mouthwashuse | |||

| No | 10.71 ± 8.0 | 3.81 ± 3.6 | 7.27 ± 7.1 |

| Yes | 13.66 ± 10.9 | 6.33 ± 3.2 | 10 ± 8.2 |

| P-value | 0.56 | 0.26 | 0.37 |

| Medical history | |||

| No | 11.06 ± 8.4 | 3.41 ± 3.3 | 7.24 ± 7.4 |

| Yes | 10.50 ± 7.7 | 7 ± 4 | 8.75 ± 6.4 |

| P-value | 0.88 | 0.027 | 0.51 |

| Drug use | |||

| No | 11.41 ± 8.5 | 3.74 ± 3.5 | 7.58 ± 7.5 |

| Yes | 7.50 ± 2.8 | 6.25 ± 4.7 | 6.87 ± 3.7 |

| P-value | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.79 |

To assess the independent effects of relevant variables on MN frequency, we conducted a multiple regression analysis including only those factors that showed significant associations in the univariate analysis of the total study population. In the final model, both alcohol consumption (P < 0.05) and exposure to IR (P < 0.05) remained statistically significant predictors. These findings indicate that both variables are independent predictors of increased MN frequency (Table 3).

| Variables | Beta | Standard Error | P-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.286 | 0.121 | 0.000 | 2.04 - 2.52 |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.970 | 0.520 | 0.046 | 0.06 - 2.00 |

| Exposure to IR | 0.745 | 0.173 | 0.000 | 0.39 - 1.09 |

Abbreviation: IR, ionizing radiation.

As seen in Table 4, the MN frequency in the endoscopy ward (percentage: 14.66 ± 12.1) was the highest among the studied wards. In comparing the studied wards with the unexposed group, a significant difference in the MN frequency was observed in all wards except for the radiology ward, where no significant difference was noted in MN frequency. Furthermore, for comparing different sections, there was no significant difference observed using ANOVA (P > 0.05).

| Groups | Mean ± SD | Range | P-Value vs Non-exposed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-exposed | 4.02 ± 3.6 | 0 - 10 | - |

| Exposed | 10.97 ± 8.2 | 1 - 30 | 0.000 |

| Radiology | 7.25 ± 7.3 | 1 - 20 | 0.52 |

| Angiography | 13.77 ± 6.7 | 2 - 20 | 0.002 |

| Endoscopy | 14.66 ± 12.1 | 3 - 30 | 0.000 |

| Operating room | 10.62 ± 6.2 | 5 - 20 | 0.02 |

5. Discussion

The potential genotoxic effect resulting from occupational exposure of medical professionals to IR has raised significant concerns within the medical community (13). Micronuclei are regarded as early biological indicators of genetic toxicity carcinogenesis (11).

Our study demonstrated that exposure to low doses of IR significantly increased the noticeable level of MN in oral mucosal cells compared to non-exposed individuals. The use of oral mucosal cells to investigate occupational genetic damage from low doses of IR has been limited in two studies, showing that the frequency of MN was significantly higher in the exposed group than in the control group (22, 23).

In this study, the highest level of MN was observed in the endoscopy group, while the lowest level was in the radiology group. Although this difference was not statistically significant, it raises questions, given that fluoroscopy-guided procedures, such as angiography, typically involve higher radiation exposure. However, several possible explanations exist. Endoscopy personnel, particularly those performing ERCP, often remain in close physical proximity to the patient and the fluoroscopy unit, which increases their exposure to scattered radiation (7, 24, 25). Furthermore, multiple studies have shown that adherence to radiation safety protocols is often suboptimal among endoscopy staff (26-28). For instance, a recent study of 159 therapeutic endoscopists found that many lacked formal training in the use of fluoroscopy systems, and the consistent use of protective equipment, such as lead glasses and shielding curtains, was low. Over half of the participants did not routinely wear a dosimeter (28). In contrast, radiology staff are generally more aware of radiation hazards and tend to operate imaging devices from shielded control rooms (7). These differences in behavior, training, and protective practices may explain the relatively higher MN frequency observed in the endoscopy group despite the expected higher risk in angiography.

Aging leads to a decline in the efficiency of DNA repair processes and the accumulation of mutations, resulting in increased levels of DNA damage (29). In our study, an increase in age did not lead to a rise in the MN levels in both exposed and non-exposed groups. The average age of both groups is approximately 38 years. Also, in the study by Aguiar Torres et al., the absence of a link between age and MN frequency may be due to the average age of participants in both groups (around 45 years). Given that participants in both groups are relatively young, they may not yet exhibit the increased levels of DNA damage typically associated with aging (22).

In our study, no significant relationship was found between work experience and MN levels. While some studies have reported an increase in MN levels with an increase in work experience (30-32), some of these studies attributed this increase to aging (31). Distinguishing whether the increase is due to aging or an increase in work experience requires further research and investigation (32).

Smoking status is usually recognized as an important factor affecting MN frequency, but in this study, it was not significantly associated with the frequency of MN (Table 3). Chemicals found in cigarette composition contain genotoxic substances (18). Bonassi et al. (33) showed that only heavy smokers (i.e., > 40 cigarettes/day) have a significant increase in MN frequency compared to nonsmokers. In our study, the tobacco consumption rates (cigarettes/day) were (3.2 ± 0.18).

In this study, two individuals from the exposed group mentioned alcohol consumption, and a significant relationship was observed between alcohol consumption and the frequency of MN (P > 0.05) (Table 3). In a study by Singh et al. (34), an increase in the frequency of MN in alcoholics and alcoholic smoker subjects as compared to healthy controls was found.

Micronuclei assays in buccal exfoliated cells have gained popularity as a minimally invasive biomarker for genomic damage in human populations. A comprehensive meta-analysis by Ceppi et al. (18), which reviewed 63 studies, highlighted important methodological considerations, including controlling for confounding factors, adequate sample size, and appropriate statistical modeling. Their findings demonstrated a strong correlation between MN frequencies in buccal cells and PBL, supporting the use of buccal MN assays as reliable and sensitive indicators of genotoxic exposure. Additionally, the meta-analysis recommended scoring a minimum of 4,000 cells to reduce variability, which contrasts with the common practice of scoring 2,000 cells. Incorporating buccal MN evaluation in occupational health studies enables large-scale, noninvasive screening while maintaining robust predictive value for genomic damage.

One of the strengths of our study is that it is among the limited studies that utilized a simple and non-invasive method to assess genetic damage resulting from chronic occupational exposure to IR; however, other environmental factors may affect the result. In this study, the control group was selected from the same workplace, which was exposed similarly in terms of demographic factors and confounding factors, and various exposure departments were also investigated.

One of the limitations of this study is the absence of dosimetry data, as participants are not routinely monitored for radiation exposure, and no official dose records are available. This restricts our ability to conduct precise dose-response analyses between IR exposure and MN frequency. Future studies should incorporate real-time personal dosimetry monitoring to quantify individual radiation doses better and to strengthen the understanding of the dose-dependent genomic effects.

5.1. Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that evaluating MN in oral mucosal cells can serve as a simple, noninvasive screening method for the early detection of genomic damage in individuals exposed to IR. Based on our findings, we tentatively suggest a threshold of > 11 MN per 1,000 cells as a potential indicator for follow-up monitoring. This value, derived from the upper limit of the MN frequency distribution in the non-exposed population, may help guide future research and screening practices. It is recommended that this method be applied in larger populations and combined with dosimetry data to better assess dose-response relationships. Healthcare professionals routinely handling IR should adhere strictly to radioprotection protocols and radiation safety guidelines, utilizing all accessible protective equipment.