1. Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a rare intermediate malignancy, characterized by the proliferation of myofibroblastic spindle cells and inflammatory cell infiltration (1). Gynecological IMTs most commonly occur in the uterine corpus but are often under-recognized and frequently misdiagnosed as smooth muscle tumors. Uterine IMT is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm, accounting for approximately 0.5 - 1% of all uterine mesenchymal tumors (2). The mean age at diagnosis is 39 years, with the majority of cases occurring in women of reproductive age. Its occurrence during pregnancy is even rarer, possibly linked to physiological changes in the uterine environment during gestation (2). As of now, fewer than 20 cases of IMT diagnosed specifically during pregnancy have been reported in the English literature. A thorough PubMed search identified only 14 cases with detailed clinical documentation, highlighting the exceptional rarity of this condition during gestation. Although the specific risk factors for uterine IMT remain unclear, some studies suggest that chronic inflammation, trauma, and hormonal alterations may contribute to its pathogenesis (3). This study reports a rare case of uterine IMT, initially misdiagnosed as a uterine fibroid during pregnancy and incidentally diagnosed during cesarean section.

2. Case Presentation

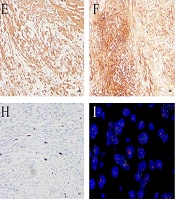

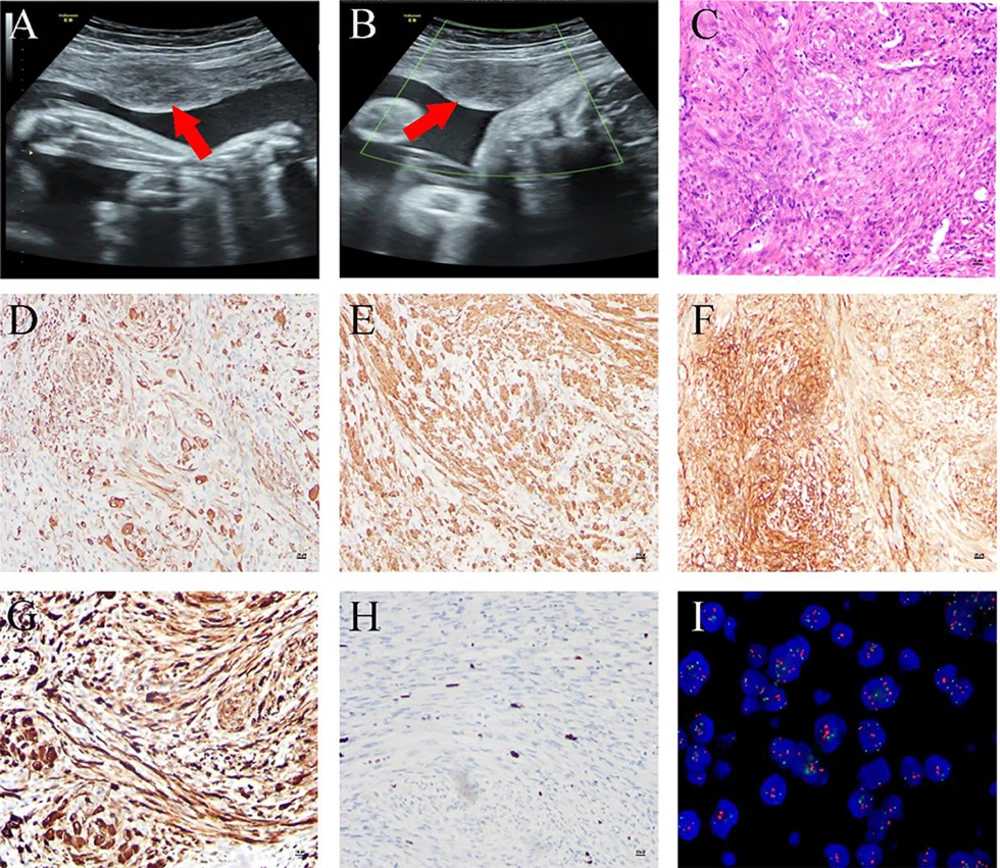

A 26-year-old female patient, primigravida (first pregnancy) with no prior history of uterine fibroids, was admitted with a complaint of amenorrhea for 40 weeks. An ultrasound conducted at 29 weeks of pregnancy revealed a singleton viable fetus and a 35 × 23 mm2 space-occupying lesion in the uterus, initially suspected to be a fibroid (Figure 1A and B). During the cesarean section, a localized myomectomy, or segmental resection, was performed to excise the mass, successfully preserving the uterus. Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed that the tumor cells were arranged in bundles, interwoven with each other, and exhibited mild morphology with occasional mitotic figures, as well as epithelial-like and ganglion-like cells in some areas; the stroma exhibited a reaction involving lymphocytes, plasma cells, and foam-like histiocytes (Figure 1C). Immunohistochemical analysis showed positive staining for desmin, SMA, CD10, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), with a Ki67 positivity rate of less than 10% (Figure 1D - H). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) confirmed the rearrangement of the ALK gene at chromosome 2p23 (Figure 1I). The postoperative pathology identified the mass as an IMT rather than a uterine fibroid. Considering the patient was in the lactation period and the lesions were confined solely to the uterus, no postoperative treatment was administered. The patient recovered well, with no complications or recurrence after a one-year follow-up.

Imaging and pathological findings of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT): A and B, the ultrasound examination at 29 weeks of pregnancy revealed a single live fetus and a 35 × 23 mm2 occupying lesion within the uterus; C, hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed that tumor cells were arranged in bundles, and the stroma was infiltrated with lymphocytes and plasma cells at a magnification of 100X; D – H, the immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated positive staining for desmin (D), SMA (E), CD10 (F), and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) (G), with a Ki67 positive rate of less than 10% (H), all observed at a magnification of 100X; I, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for detecting ALK rearrangement.

3. Discussion

The IMT is an uncommon neoplasm that typically arises in the hollow viscera of children and young adults, with uterine involvement being particularly rare (4, 5). While non-gestational uterine IMTs usually occur in premenopausal women presenting with symptoms like abdominopelvic pain or abnormal bleeding (6), IMTs diagnosed during the perinatal period appear to follow a distinct clinical course.

In stark contrast to the typical presentation, our case and a review of similar perinatal cases summarized in Table 1 (7-13) revealed that these lesions are frequently asymptomatic and discovered incidentally during routine prenatal examinations or cesarean sections. From a molecular standpoint, the ALK rearrangement is a key diagnostic feature. The majority of reported uterine IMTs are positive for ALK by both IHC and FISH. For the subset of ALK-negative tumors, further molecular testing is crucial. We recommend screening for alternative oncogenic drivers, such as fusions involving RET (14), ROS1 (15), and ETV6-NTRK3 (16), as these have also been identified in ALK-negative uterine IMTs and may have therapeutic implications.

| Age (y) | Clinical Data | Concomitant Diseases | Location | Size (cm) | ALK Status | Management | Follow-up (mo) | Recurrence/Metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | Asymptomatic | No | Placenta | 2 | Negative | The placenta was expelled along with the enveloped mass, and an elective total hysterectomy was performed. | 59 | No |

| 30 | Asymptomatic | Gestational hypertension and anemia | Placenta | 3.3 | Negative | The placenta was expelled along with the enveloped mass. | NA | NA |

| 33 | Asymptomatic | No | Placenta | 2 | Positive | The placenta was expelled along with the enveloped mass. | NA | NA |

| 25 | Asymptomatic | No | Placenta | 5 | Positive | The mass was expelled along with the placenta. | NA | NA |

| 31 | Asymptomatic | No | Placenta | 5.1 | Positive | The placenta was expelled along with the enveloped mass. | 5 | No |

| 30 | Asymptomatic | No | Uterine corpus | 9 | Positive | The mass was removed after delivery of the placenta. | NA | NA |

| 33 | Asymptomatic | No | Placenta | 3.5 | Negative | The mass was expelled along with the placenta, and an elective total hysterectomy was performed. | 19 | No |

| 29 | Asymptomatic | No | Placenta | 1.5 | Positive | The placenta was expelled along with the enveloped mass. | NA | NA |

| 41 | Asymptomatic | No | Uterine corpus | 4 | Positive | The mass was removed after delivery of the placenta. | NA | NA |

| 39 | Asymptomatic | No | Placenta | 6.5 | Negative | The placenta was expelled along with the enveloped mass. | NA | NA |

| 44 | Asymptomatic | No | Uterine corpus | 5.9 | Positive | The mass was expelled along with the placenta. | 7 | No |

| NA | Asymptomatic | No | Placenta | 1.5 | Positive | The placenta was expelled along with the enveloped mass. | NA | NA |

| 37 | Asymptomatic | Gestational diabetes mellitus | Uterine corpus | 7.7 | Negative | The mass was removed after delivery of the placenta. | 9 | No |

| 33 | Pelvic mass | No | Uterine corpus | 4.7 | Positive | Laparoscopic myomectomy | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; NA, not available.

The management of IMT lacks a standardized therapeutic protocol, and treatment strategies are typically tailored to the disease stage. For localized, resectable tumors, complete surgical excision is the cornerstone of therapy and is often curative. In contrast, for patients with advanced, unresectable, or metastatic disease, systemic therapy is the recommended approach. Notably, clinical evidence from the China Children's Cancer Group has demonstrated that a regimen combining methotrexate and vinorelbine offers significant efficacy and a favorable safety profile, positioning it as a promising first-line treatment for advanced IMT (17). Radiation therapy may serve as an adjunctive treatment following incomplete resection, but it is not advised for patients with fertility concerns. Given that over 50% of patients exhibit ALK rearrangements, ALK inhibitors could offer an alternative therapeutic option for patients with ALK-positive IMT.

The recurrence rate of IMT is approximately 20%, whereas for pelvic IMT, it is notably higher, at 85%. Furthermore, around 5% of patients may experience distant metastasis (4). Consequently, standardized treatment and regular follow-up are essential.

3.1. Conclusions

This report underscores that uterine IMTs, though rare, must be considered in the differential diagnosis of uterine masses detected during pregnancy, as they can be clinically silent and mimic leiomyomas on routine antenatal imaging. The definitive diagnosis hinges on meticulous histopathological assessment demonstrating characteristic spindle cells and inflammatory infiltrates, supplemented by immunohistochemistry (notably ALK positivity) and molecular confirmation of ALK rearrangement. Although our patient achieved an excellent outcome with surgical excision alone, reflecting the typical management for localized disease, the documented potential for recurrence and metastasis, particularly in pelvic sites, mandates that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion for IMT and ensure appropriate histologic evaluation of suspicious masses. Long-term surveillance remains crucial.