1. Background

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a genetically heterogeneous hematologic malignancy characterized by clonal expansion of immature myeloid cells and impaired differentiation. Due to its biological complexity, treatment options remain limited; however, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) offers curative potential, particularly for high-risk patients. Post-transplant relapse, occurring in 30 - 50% of cases, remains a significant challenge, underscoring the need for predictive biomarkers to guide post-HSCT monitoring and intervention (1). Current strategies focus on chimerism analysis and minimal residual disease (MRD) detection, but molecular profiling of genes governing stemness and differentiation shows promise for improving relapse prediction.

KMT2A (lysine methyltransferase 2A), also known as MLL1, is a pivotal epigenetic regulator essential for hematopoiesis, orchestrating transcriptional programs via histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation (2). While KMT2A rearrangements are established drivers of high-risk AML, wild-type KMT2A maintains hematopoietic homeostasis by modulating downstream targets (HOXA9, MEIS1, PRDM16) (3, 4). These genes collectively regulate stem cell self-renewal, lineage specification, and metabolic balance (5). Research has shown that KMT2A plays a role in leukemogenesis by disrupting oncogenic pathways and modifying transcriptional programs vital for hematopoietic development, even in the absence of chromosomal rearrangements (4, 6, 7). Dysregulation of this axis may impair differentiation and promote leukemogenesis, potentially affecting post-HSCT outcomes.

HOXA9, a transcription factor critical for hematopoietic progenitor expansion, is tightly regulated under physiological conditions. Its activity is controlled by KMT2A, ensuring balanced proliferation and differentiation (8). Aberrant HOXA9 overexpression correlates with poor AML prognosis independent of KMT2A rearrangements, suggesting its utility as an independent prognostic marker (9). MEIS1, which enhances HOXA9-mediated transcriptional activity, collaborates with KMT2A dysfunction to impede differentiation. KMT2A acts as a molecular scaffold, coordinating gene interactions to maintain the balance between stem cell renewal and differentiation (10).

PRDM16, a context-dependent transcriptional regulator, further influences lineage fidelity and stem cell integrity under KMT2A regulation. It participates in stem cell maintenance, erythroid-myeloid commitment, and cellular metabolism (11). Collectively, these genes form a network whose expression patterns may signify residual leukemic potential or early relapse post-HSCT.

Recent studies highlighted the prognostic significance of KMT2A and its downstream pathways in AML. CRISPR-mediated KMT2A deletion in non-rearranged AML models reduces HOXA9 cluster expression and impairs leukemic survival (12). Transcriptional profiling similarly identifies aberrant HOXA9/MEIS1 overexpression as a predictor of relapse, even without KMT2A fusions (13). These findings underscore the potential of KMT2A and associated genes as biomarkers for risk stratification in HSCT recipients.

2. Objectives

Based on this evidence, we investigated the expression patterns of KMT2A, HOXA9, MEIS1, and PRDM16 to evaluate whether their co-expression correlates with disease progression and clinical outcomes in AML patients undergoing HSCT. Such associations could establish a predictive signature for risk stratification. Unlike prior studies focusing on KMT2A rearrangements, this work examined the understudied role of wild-type KMT2A in post-transplant surveillance. Insights from this research may enable earlier relapse detection and inform personalized therapeutic strategies to improve outcomes for high-risk AML patients.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population

This study enrolled 42 participants at Taleghani Hospital, Tehran, Iran between March 2024 and March 2025: Fifteen controls without hematologic malignancies, 12 de novo AML patients, and 15 AML patients who received allogeneic HSCT.

3.2. Sample Collection

The control group comprised individuals referred for bone marrow (BM) evaluation due to clinical suspicion of hematologic malignancy (e.g., constitutional symptoms, unexplained cytopenia, or aberrant peripheral blood findings). Comprehensive diagnostic workups (morphology, flow cytometry, cytogenetics, molecular testing) confirmed no hematologic malignancy or clonal abnormalities. For the HSCT-AML group, BM aspirates were obtained at day +30 post-HSCT to assess stable engraftment, residual disease, and initial treatment response. This time point aligns with clinical guidelines for evaluating donor engraftment, hematopoietic recovery, and early relapse markers. Demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

3.3. Ethics Considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1403.258) and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent after receiving information about the study’s objectives, procedures, risks, and benefits.

3.4. RNA Extraction, Complementary DNA Synthesis, and Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from BM cells using TRIzol™ reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). RNA integrity was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis; concentration and purity were determined using a NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer. RNA was stored at -80°C until use. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using a Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA). Synthesized cDNA was stored at -20°C until performing quantitative real-time PCR. Gene expression (KMT2A, HOXA9, MEIS1, PRDM16) was quantified by qRT-PCR using SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Amplicon, Denmark) on an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system. GAPDH served as the reference gene to normalize the expression levels of the target genes. Relative expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method.

3.5. Primer Design and Validation

Primers for KMT2A, HOXA9, MEIS1, PRDM16, and GAPDH were designed via Primer-BLAST (NCBI) and synthesized (Metabion, Germany). Annealing temperatures were optimized at ~ 60°C. Specificity was confirmed by conventional PCR (agarose gel electrophoresis) and post-qRT-PCR melting curve analysis. Primer sequences and amplicon sizes are listed in Appendix 2 in Supplementary File.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad SoftwareGroup comparisons were conducted using Kruskal-Wallis tests, followed by Dunn’s post hoc analysis. Gene expression correlations used Spearman’s rank test. Diagnostic accuracy was evaluated via ROC curves. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was assessed by Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank tests. All tests were two-tailed; P-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Bars are marked with asteriks to denote the level of statistical significance based on the calculated p-values: * (p < 0.5), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), **** (p < 0.0001), and ns (not significant, p > 0.05).

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The HSCT-AML cohort (n = 15) had a median age of 40 years (range: 32 - 66), with 7 (47%) males and 8 (53%) females. FAB subtypes: M2 (33%), M1 (27%), M4 (20%), M5 (13%), and mixed (7%). Molecular profiling revealed FLT3-ITD mutations (33%), wild-type FLT3 (53%), IDH1/2 mutations (7%), and BCR/ABL p190 (7%). Cytogenetic investigation revealed normal karyotypes in 6 (40%) of cases, with abnormalities including t(9;22) (7%), inv(16) (7%), del(5) (7%), and t(9;6) (7%); 26% of cytogenetic findings were unavailable.

All patients underwent HSCT: Allogeneic (80%, n = 12) or haploidentical (20%, n = 3). The median age of the donor was 39 years (range: 34 - 61), and the graft parameters were median WBC (12.1 × 108/kg), MNC (8.6 × 108/kg), and CD34+ cell counts (8.1 × 106/kg). The median time for successful engraftment was 15 days (range: 14 - 17). According to the NCCN Guidelines (v3.2024, AML-B, POST-1), relapse occurred in 5 of 15 patients (33%), with a median interval to relapse of 3 months (range: 1 - 6) (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 40 (32 - 66) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 7 (47) |

| Female | 8 (53) |

| FAB classification | |

| M1 | 4 (27) |

| M2 | 5 (33) |

| M4 | 3 (20) |

| M5 | 2 (13) |

| Mixed | 1 (7) |

| Molecular | |

| Wild (FLT3-ITD) | 5 (33) |

| Mutant (FLT3-ITD) | 8 (53) |

| IDH1/2 positive | 1 (7) |

| BCR/ABL p190 | 1 (7) |

| Karyotype | |

| Normal | 6 (40) |

| Abnormal b | 4 (27) |

| Unknown | 5 (33) |

| Cytogenetic risk | |

| Favorable | 0 (0) |

| Intermediate | 11 (73) |

| Adverse | 3 (20) |

| Laboratory data pre-HSCT | |

| WBC (×109/L) | 7.72 (3.1 - 16.2) |

| Hb (×g/L) | 12 (9.6 - 14.4) |

| Plt (×109/L) | 202 (60 - 318) |

| Relapse | |

| Non-relapse | 10 (67) |

| Relapse | 5 (33) |

| Time to relapse (mo) | 3 (1 - 6) |

| Transplant | |

| Allogenic | 12 (80) |

| Haplotype | 3 (20) |

| Donor characteristics | |

| Donor age (y) | 39 (34 - 61) |

| Graft characteristics | |

| WBC (×108/Kg) | 12.1 (10.7 - 15.3) |

| MNC (×108/Kg) | 8.6 (7.9 - 9.5) |

| CD34+ (×106/Kg) | 8.1 (7.3 - 8.9) |

| Engraftment (d) | 15 (14 - 17) |

Abbreviations: HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; MNC, mononuclear cells.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean (range).

b Abnormalities including t(9;22), inv(16), del(5), and t(9;6).

4.2. Expression Patterns of Four Genes Across Study Groups

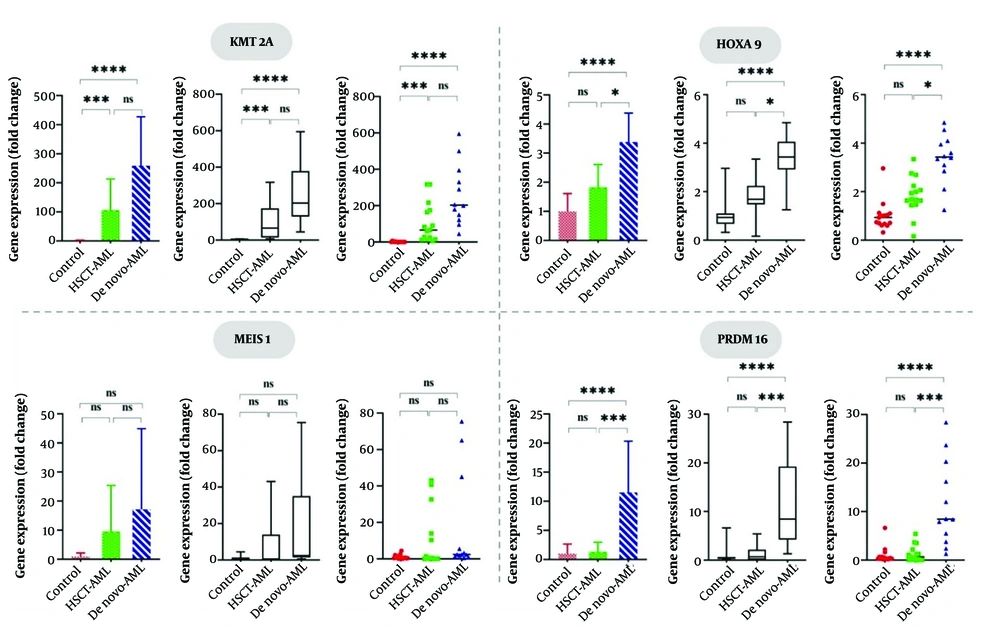

Gene expression analysis utilizing Kruskal-Wallis tests demonstrated substantial differences in KMT2A (H = 31.63, P < 0.0001), HOXA9 (H = 24.69, P < 0.0001), and PRDM16 (H = 21.89, P < 0.0001) among the control, HSCT-AML, and de novo AML groups, while MEIS1 expression exhibited no statistically significant variation (H = 3.635, P = 0.162) (Table 2).

| Genes and Groups | Mean ± SD | Median | Test Statistic | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMT2A | 31.63 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Control | 1.00 ± 1.78 | 0.12 | ||

| HSCT-AM | 105.94 ± 107.63 | 65.47 | ||

| de novo AML | 259.10 ± 154.99 | 203.18 | ||

| HOXA9 | 24.69 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Control | 1.00 ± 0.61 | 0.94 | ||

| HSCT-AM | 1.82 ± 0.79 | 1.68 | ||

| de novo-AML | 3.38 ± 1.02 | 3.43 | ||

| MEIS1 | 3.635 | 0.162 | ||

| Control | 1.00 ± 1.18 | 0.53 | ||

| HSCT-AM | 9.57 ± 15.82 | 0.49 | ||

| de novo AML | 17.21 ± 22.27 | 2.40 | ||

| PRDM16 | 21.89 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Control | 1.00 ± 1.66 | 0.41 | ||

| HSCT-AM | 1.33 ± 1.65 | 0.69 | ||

| de novo AML | 11.50 ± 8.52 | 8.45 |

Abbreviations: HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

As shown in Figure 1, post hoc Dunn’s tests indicated that there was no significant difference between the HSCT-AML and AML groups. However, KMT2A expression was significantly higher in both the HSCT-AML and de novo AML groups compared to the control group, with a P-value of less than 0.0001 for both comparisons. HOXA9 expression exhibited a graded expression pattern, with the highest expression levels in de novo AML, moderate expression in HSCT-AML, and minimal expression in controls (P < 0.0001 for AML vs. controls, P < 0.05 for AML vs. HSCT-AML). Interestingly, PRDM16 overexpression was confined to de novo AML and considerably different from controls and HSCT-AML (P < 0.0001 for both). MEIS1 demonstrated a non-significant increasing trend in the AML group (median: 2.40 in de novo AML compared to 0.49 in HSCT-AML and 0.53 in controls), potentially disguised by substantial intra-group variability (e.g., SD = 15.82 in HSCT-AML). These findings demonstrate that PRDM16 could be a prospective diagnostic marker for de novo AML, while KMT2A and HOXA9 indicated extensive transcriptional dysregulation among two related AML subgroups.

Differential gene expression among study groups; KMT2A and HOXA9 are highly overexpressed in AML subgroups, however PRDM16 overexpression is exclusive to de novo AML, indicating its potential as a diagnostic marker. (*, P < 0.05 ; **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, ****, P < 0.0001; and ns, not significant, P ≥ 0.05).

4.3. Association Between Gene Expression and Clinicopathological Characteristics

To assess potential associations between gene expression patterns and clinicopathological features in HSCT-AML patients, patients were stratified by mean expression levels into low- and high-expression groups. Statistical analyses (Mann-Whitney U and Spearman rank tests) revealed no significant correlations of KMT2A, HOXA9, or MEIS1 with age, relapse status, transplant type, cytogenetic risk, or routine laboratory parameters (all P > 0.05). In contrast, elevated PRDM16 expression was significantly associated with higher platelet counts (273 vs. 176 × 10⁹/L; P = 0.019) and greater CD34⁺ cell doses in allografts (10.80 vs. 7.53 × 10⁶/Kg; P = 0.032), suggesting a role in post-transplant hematopoietic reconstitution. While PRDM16 demonstrated unique clinicopathological relevance, no other genes exhibited significant associations. The generalizability of these findings is constrained by cohort size limitations (Appendix 3 in Supplementary File).

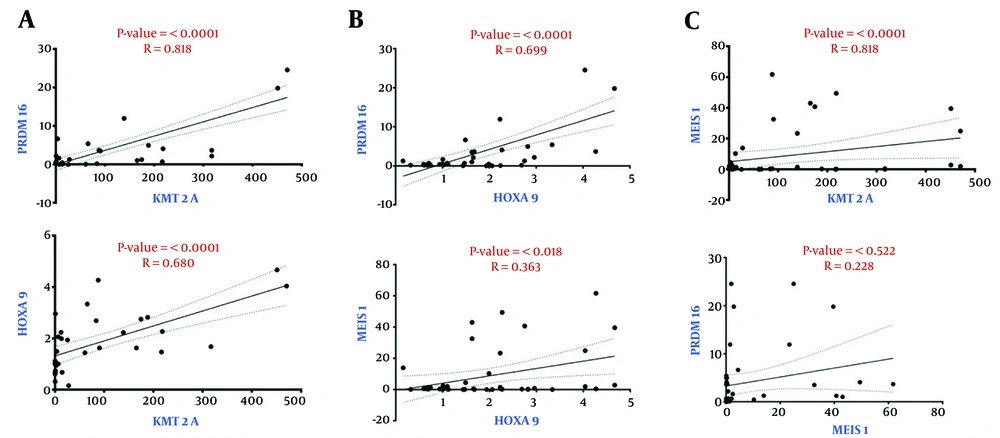

4.4. Correlation Analysis of Gene Expression

The correlation between the expression of the KMT2A, HOXA9, MEIS1, and PRDM16 genes was assessed using Spearman correlation analysis. There was a significant and statistically significant positive connection between KMT2A and PRDM16 (r = 0.818, P < 0.0001) and HOXA9 (r = 0.680, P < 0.0001) (Figure 2A). Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between HOXA9 expression and PRDM16 (r = 0.699, P < 0.0001) and MEIS1 (r = 0.363, P = 0.018) (Figure 2B). Nevertheless, the correlation between KMT2A and MEIS1 was not statistically significant (r = 0.295, P = 0.057), nor was the association between MEIS1 and PRDM16 (r = 0.229, P = 0.146) (Figure 2C). These results suggested the strong co-expression patterns among specific gene pairs, including KMT2A, HOXA9, and PRDM16, while MEIS1 showed a weaker or non-significant association with KMT2A and PRDM16.

Spearman correlation analysis of gene expression levels. A, a strong, statistically significant positive correlated was found between KMT2A and PRDM16, as well as between KMT2A and HOXA9; B, there were weaker but still significant correlations between HOXA9 and PRDM16 and MEIS1; C, MEIS1 failed to exhibit any significant correlation with KMT2A or PRDM16.

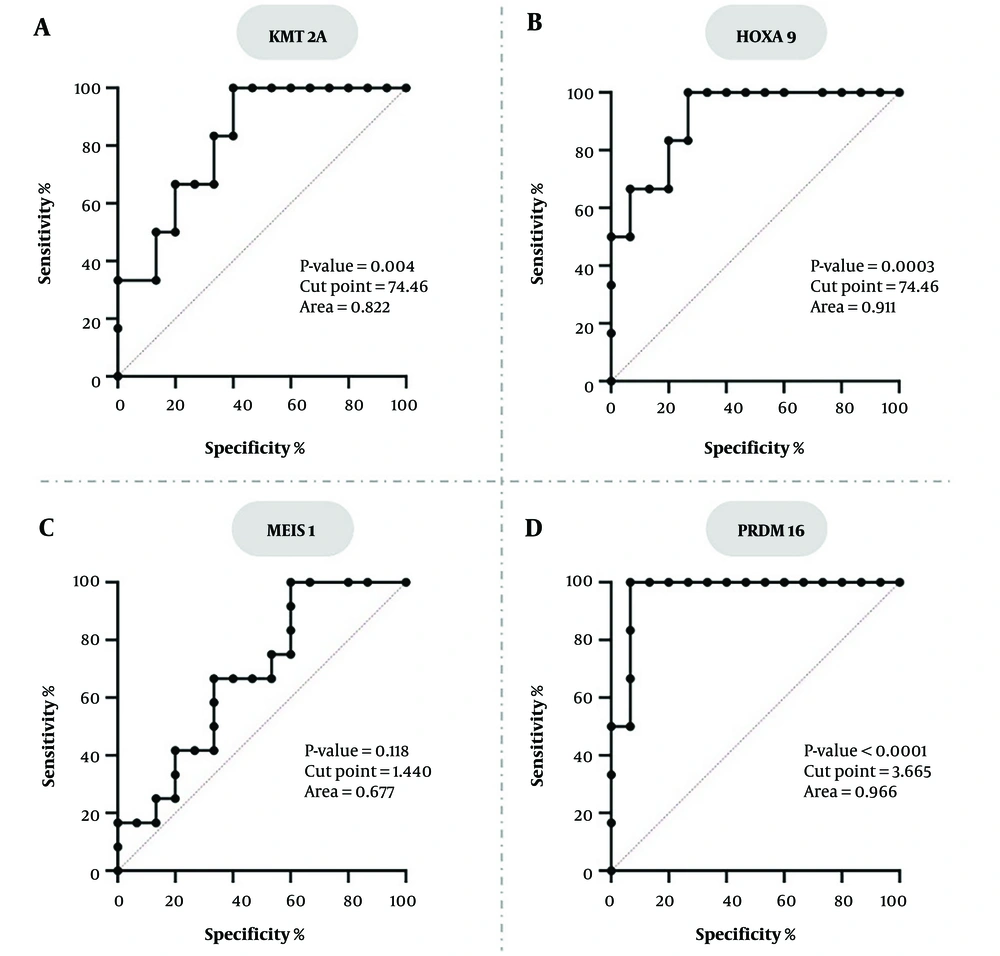

4.5. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Analysis

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of KMT2A, HOXA9, MEIS1, and PRDM16 gene expression levels in distinguishing AML patients from healthy individuals, ROC curve analysis was performed. KMT2A and HOXA9 displayed a high sensitivity of 100% for both. However, their specificity was relatively low at 53.33% for both markers, leading to moderate Youden indices of 53.33. KMT2A had a lower yet still significant area under the curve (AUC) of 0.822 (95% CI: 0.666 - 0.978; P = 0.004), while HOXA9 showed a higher accuracy with an AUC of 0.911 (P = 0.0003). The MEIS1 gene exhibited the lowest performance, evidenced by a non-significant AUC of 0.677 (95% CI: 0.474 - 0.881; P = 0.118). At its ideal cut-point of 1.440, MEIS1 demonstrated balanced but low sensitivity and specificity, both at 66.67%, resulting in a Youden Index of 33.34. Conversely, the PRDM16 gene exhibited exceptional discriminatory potential, with an AUC of 0.966 (95% CI: 0.898 - 1.000; P < 0.0001), achieving 100% sensitivity and 93.33% specificity at an optimal cut point of 3.665. The Youden Index for PRDM16 was the highest among all genes (93.33), signifying its strong overall diagnostic precision (Figure 3). In conclusion, PRDM16 has proven to be the most promising biomarker, exhibiting exceptional sensitivity, specificity, and AUC. HOXA9 and KMT2A showed high sensitivity but restricted specificity, whereas MEIS1 showed inadequate diagnostic efficacy overall.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for the accuracy of gene expression in distinguishing AML patients from healthy individuals. A, KMT2A; and B, HOXA9 show high sensitivity but lower specificity; C, MEIS1 does not work well as a diagnostic tool because the AUC is not significant; D, PRDM16 has an AUC of 0.966, so it can distinguish groups well.

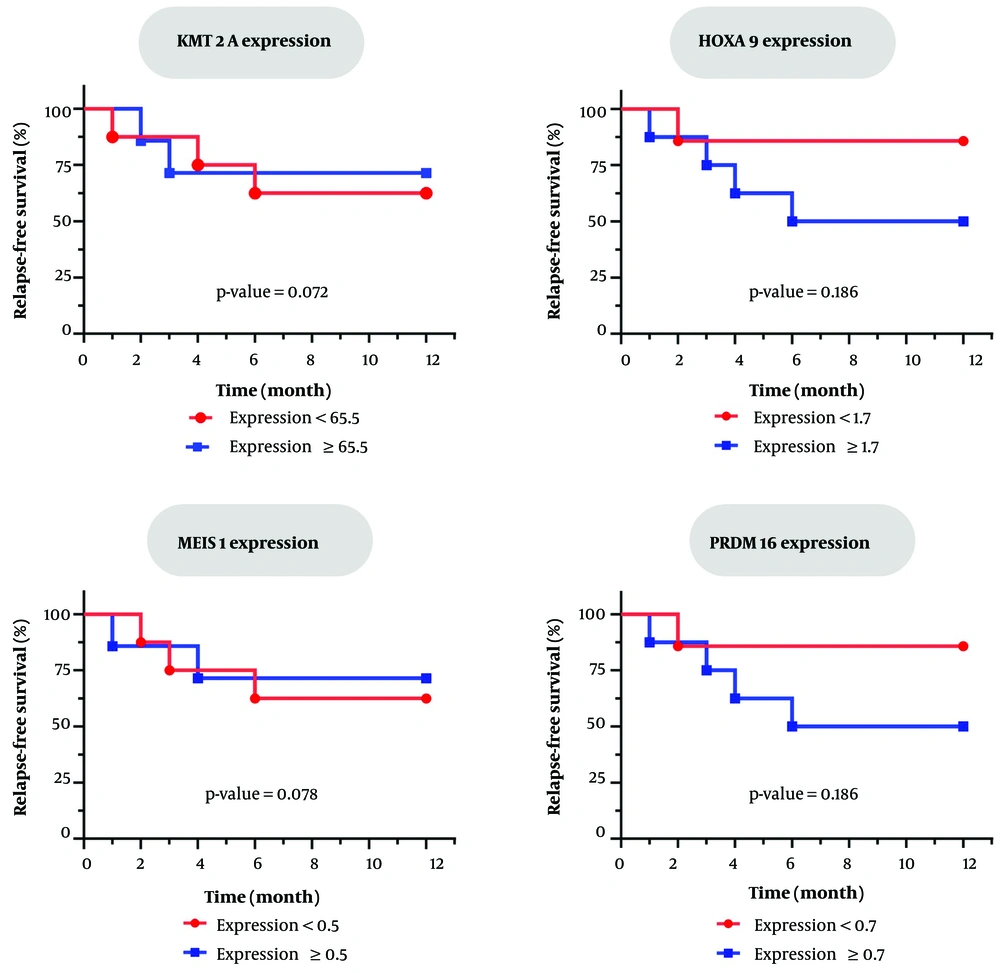

4.6. Correlation of Gene Expression on Early Relapse

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Log-rank testing were conducted to evaluate the association between gene expression levels and the risk of early relapse in AML patients following HSCT. Patients were categorized into high- and low-expression groups based on median expression values. Overall, 5/15 (33%) of patients experienced relapse within 1 - 6 months post-transplant.

Although quantitative patterns have been observed in specific genes (for example, higher relapse associated with increased PRDM16 or HOXA9 expression), no statistically significant correlation was established between the expression levels of any gene and relapse risk (P > 0.05 for all Log-rank tests) (Figure 4). The results indicated that, although certain genes display suggestive patterns, none independently predicted relapse risk in this population. In conclusion, gene expression levels demonstrated no significant association with disease relapse outcomes in post-transplant patients. These results highlighted the need for larger, more extensive studies or the creation of multi-gene models to improve prognostic biomarkers.

5. Discussion

AML relapse following HSCT is a major cause of treatment failure, with post-transplant relapse rates above 30 - 40% in high-risk populations and a decline in the median survival to under 6 months after relapse. This clinical challenge underscores the need for biomarkers that stratify relapse risk. Current monitoring strategies (chimerism, and blood counts) often detect relapse at advanced stages, highlighting the necessity for biomarkers reflecting the biological mechanisms of AML persistence

Wild-type KMT2A, despite the absence of chromosomal rearrangements, contributes to leukemogenesis by dysregulating downstream pathways (HOXA9, MEIS1, PRDM16) essential for hematopoietic development (4, 6, 7). These genes, involved in transcriptional dysregulation, epigenetic remodeling, and LSC maintenance, are emerging as promising biomarkers. For example, KMT2A sustains HOXA9/MEIS1 expression via H3K4 methylation, promoting LSC self-renewal (14). The expression patterns of these genes in de novo AML are becoming clearer. However, we still don’t fully understand their dynamics in the post-transplant setting and potential association with relapse risk. Our study addresses the gap by evaluating the expression profiles of these genes in AML patients following allogeneic HSCT.

We observed significantly elevated KMT2A expression in de novo AML and post-HSCT AML compared to controls, emphasizing its role in leukemogenesis independent of rearrangements. This upregulation may sustain residual disease through aberrant transcriptional programming.

The strong KMT2A-HOXA9 correlation (r = 0.680, P < 0.0001) supports KMT2A’s regulation of a HOXA network, consistent with its facilitation of oncogenic programs via HOXA9/MEIS1 activation (15). Mohamed et al. investigated HOXA9 expression in sixty AML samples and found that elevated HOXA9 expression correlates with a poor prognosis and impaired treatment response in these patients and serves as an independent predictive factor influencing chemotherapy outcomes (16). Similarly, Xie et al. illustrated that methylation of HOXA9 is a promising biomarker for risk stratification and treatment optimization in AML (17).

HOXA9 was highest in de novo AML and moderately elevated post-HSCT, suggesting involvement in leukemogenesis rather than relapse mechanisms. Its strong correlation with PRDM16 (r = 0.699) and MEIS1 (r = 0.363) indicates coordinated regulation in AML pathogenesis, aligning with reports of elevated HOXA9 cluster expression predicting unfavorable outcomes. Chen et al. also noted that HOXA2-10 mRNA expression levels were markedly increased in AML, and that high HOXA1-10 expression correlated with unfavorable prognosis in AML patients. Their findings demonstrated a favorable correlation between the expression of the HOXA9 gene and the expression of the MEIS1 gene (18). These findings agree with Gao et al., who demonstrated that AML patients have elevated levels of HOXA9 and MEIS1 in comparison to healthy BM donors (19). They demonstrated that HOXA9 expression could serve as a promising biomarker to enhance a predictive model for predicting clinical outcomes and facilitating personalized treatment in individuals with AML (19).

PRDM16 overexpression was exclusive to de novo AML and demonstrated exceptional diagnostic accuracy (AUC = 0.966), supporting its utility as an AML biomarker. Its strong correlation with KMT2A (r = 0.818) positions it within a KMT2A-mediated epigenetic network. Consistent with our findings, Xiang et al. showed that PRDM16 expression is a crucial prognostic indicator in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia (CN-AML). These findings highlight PRDM16 as a prospective marker for risk assessment and therapeutic decision-making in CN-AML, especially in highlighting patients who may benefit from HSCT (20). Similarly, high PRDM16 expression was demonstrated by Dao et al. to be an independent poor prognostic factor in 267 adult AMLs with intermediate cytogenetic risk, including a cohort with normal cytogenetics (21).

MEIS1 showed non-significant elevation and limited diagnostic value (AUC = 0.677), potentially due to regulatory heterogeneity or dependence on HOXA9. The non-significant KMT2A-MEIS1 correlation (r = 0.295, P = 0.057) suggests context-specific regulation. In agreement with our findings, Abdelrahman et al. demonstrated remarkable overexpression of HOXA9 and MEIS1 in 91 Egyptian AML patients relative to 41 healthy controls. Despite their diagnostic capacity (AUC = 0.910 for HOXA9 and 0.831 for MEIS1), no correlation was observed between their expression levels and clinical outcomes (P > 0.05). These findings established HOXA9 and MEIS1 as potential diagnostic biomarkers in AML, although they underscore their restricted use in prognostic classification (22).

Critically, no gene predicted early relapse in our cohort. This may reflect the day +30 sampling time point, which may not capture molecular relapse dynamics. Alternatively, gene expression alone may be insufficient for relapse prediction, necessitating integration with other biomarkers (e.g., chimerism, MRD, and immune profiling).

5.1. Conclusions

Our results demonstrate differential expression of KMT2A, HOXA9, and PRDM16 in AML and post-HSCT patients, with PRDM16 emerging as a robust diagnostic biomarker in distinguishing AML patients from healthy individuals. While not predictive of early relapse in this cohort, these genes show potential for inclusion in multi-parameter risk models. Future studies should integrate longitudinal gene expression profiling with functional analyses to define the role of this regulatory network in AML progression and post-transplant relapse.

5.2. Limitations

Key limitations included the small sample size (particularly for relapse analysis) and single time point assessment (day +30). The assessment of gene expression at a single time point represents a key constraint, as it cannot capture the dynamic evolution of molecular markers over time. Future studies should incorporate serial monitoring at multiple intervals (e.g., days +30, +60, +90, and +180) to better define the trajectory of gene expression and its correlation with relapse kinetics. Longitudinal profiling and larger cohorts are needed to validate predictive utility. Functional studies are required to elucidate the molecular interplay between HOXA9/PRDM16 co-expression and AML progression.