1. Background

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSSC) represents the most common malignancy of the head and neck, accounting for roughly 260,000 new cases and 124,000 deaths worldwide annually (1). Approximately 90% of oral cancers are squamous cell carcinomas and are the most prevalent form of oral cancer (2, 3), and among these, lesions occurring on the tongue — tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC) — are the most prevalent, mostly involving the dorsal, ventral, and lateral borders. The prevalence of TSCC in patients younger than 45 years has increased over recent decades (4). Late-stage diagnosis remains common and strongly compromises survival, highlighting the need for early detection and for biomarkers that show the molecular mechanisms determining tumor progression.

The etiology of OSCC is multifactorial. Tobacco smoke and alcohol have synergistic carcinogenic effects (5), while smokeless tobacco and areca-nut use dominate the risk profiles in South-Asian populations (6). High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV), notably subtypes 16 and 18, contributes to oropharyngeal carcinogenesis (7). Environmental exposures activate oncogenes such as RAS, MYC, and EGFR and inhibit tumor-suppressor genes, including p16, TP53, and pRb, promoting malignant transformation (8). Yet, tumor size and nodal or distant spread remain the principal clinical prognosticators, as codified by TNM staging (9). Because metastatic dissemination and local recurrence account for most TSCC deaths, the discovery of molecular pathways that regulate invasion, angiogenesis, and stem-cell renewal is clinically critical.

Recent attention has focused on the Hedgehog (HH) signaling cascade, a developmental pathway that directs cell proliferation, differentiation, and tissue repair but is abnormally activated in numerous malignancies (10, 11). Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), the most profusely expressed HH ligand, binds the PTCH1 receptor to initiate downstream gene transcription and can foster cancer-stem-cell maintenance, angiogenesis, and metastasis (12). Although pharmacologic HH blockade has entered clinical practice for other tumors (13), its role in head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and, specifically, TSCC remains incompletely defined. Existing studies suggest that heightened SHH expression correlates with tumor invasion, advanced stage, and diminished survival (14, 15), but sample sizes have been limited, and findings have been heterogeneous. Moreover, the gradation of SHH expression across well-, moderately-, and poorly differentiated TSCC has received scant evaluation (16, 17).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to clarify its prognostic significance.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional laboratory study was conducted at the Mashhad School of Dentistry on forty-eight formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks, comprising well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated TSCCs alongside control mucosa samples. These were retrieved from the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Mashhad Dental School, following approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IR.MUMS.DENTISTRY.REC.1403.081).

The data collection from the patients' records and laboratory analyses was performed over six months, from June 2024 to December 2024.

Only specimens accompanied by complete clinicopathological documentation and adequate remaining tissue were included. Blocks exhibiting autolysis, fixation artifacts, or insufficient material for immune histochemistry (IHC) were excluded.

3.1. Immunohistochemistry

Sections of 4 - 5 µm thickness were cut from paraffin blocks and mounted on poly-L-lysine-coated slides. After drying, tissues were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was performed using Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) in a microwave oven. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.3% H2O2/methanol.

Sections were incubated with rabbit monoclonal anti-SHH antibody (Abcam, ab73958) at a 1:150 dilution for 60 minutes at room temperature. After washing, detection was carried out using the HRP-polymer system (EnVision™) with DAB chromogen. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, cleared, and mounted.

Positive and negative controls were included in each staining batch to ensure the specificity and reliability of the results. All procedures followed standardized protocols with appropriate quality control measures. All stained slides were examined independently by two experienced oral pathologists blinded to clinicopathological data; disagreements were resolved by cooperative review to reach agreement.

3.2. Evaluation of Immunohistochemical Staining

Cytoplasmic and nuclear staining were evaluated separately because SHH translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus is implicated in HH-pathway activation. To systematically analyze the tissue samples, a semi-quantification method was used to measure how strongly and widely a target protein (the "immunoreactivity") was present. This measurement is called "semi-quantification" because it provides a standardized score rather than an absolute, continuous measurement. The specific scoring system employed was the immunoreactive score (IRS), developed by Remmele and Stegner. This is a widely recognized method in immunohistochemistry that combines two key pieces of information into a single one. The IRS was derived by multiplying a score for the percentage of positive cells (PP) by a score for staining intensity (SI), and was subsequently categorized into four ordinal groups for statistical analysis (Table 1).

| Scores | PP (%) | SI | IRS Points – PP × SI | IRS Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No staining | No color reaction | 0 - 1 | Negative |

| 1 | < 10 | Weak reaction | 2 - 3 | Positive, weak expression |

| 2 | 11 - 50 | Moderate reaction | 4 - 8 | Positive, moderate expression |

| 3 | 51 - 80 | Strong reaction | 9 - 12 | Positive, strong expression |

| 4 | > 80 |

Abbreviations: PP, percentage of positive cells; SI, staining intensity; IRS, immunoreactive score.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Sample size was calculated based on the study by Srinath et al. (18), with the power of the study set at 80% and an α error of 5%.

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 26. Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and comparisons among the four study groups were performed using Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum tests with Dunn-Bonferroni post-hoc adjustments. Associations between categorical staining scores and tumor grade were interrogated via χ2 tests. All analyses were two-tailed, and P-values < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. To evaluate inter-observer concordance, Cohen’s κ coefficients were calculated for binary (positive/negative) and ordinal (IRS category) classifications. There was no statistically significant difference in the distribution of age (P = 0.248) or gender (P = 1.000) between the groups. Since the primary potential confounders were balanced, the risk of bias from these factors was considered low.

4. Results

The study cohort comprised 48 patients with an equal gender distribution of 24 (50%) women and 24 (50%) men, with a mean age of 57.1 ± 12.6 years (range: 23 - 93 years). Specimens were categorized into four groups: Normal tissue (n = 12), grade I TSCC (n = 12), grade II TSCC (n = 12), and grade III TSCC (n = 12). Assessment of age distribution normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test revealed a normal distribution in the normal tissue group (W = 0.912, P = 0.229), the grade I group (W = 0.924, P = 0.321), and the grade II group (W = 0.937, P = 0.466). However, the grade III group exhibited a non-normal distribution (W = 0.804, P = 0.010), thereby necessitating the use of non-parametric statistical tests for subsequent analyses. Age ranges across the groups were as follows: Normal tissue (33 - 73 years), grade I (42 - 93 years), grade II (51 - 72 years), and grade III (23 - 69 years). Mean ages were 50.25 ± 14.19 years for normal tissue, 61.25 ± 13.92 years for grade I, 60.17 ± 7.25 years for grade II, and 56.67 ± 12.34 years for grade III. Kruskal-Wallis analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in age distribution among groups (χ2 = 4.13, P = 0.248; Table 2).

| Groups | N | Mean ± SD (y) | Median (IQR) | Range | Shapiro-Wilk Statistic | df | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal tissue | 12 | 50.25 ± 14.19 | 47 (26) | 33 - 73 | 0.912 | 12 | 0.229 |

| Grade I | 12 | 61.25 ± 13.92 | 60 (12) | 42 - 93 | 0.924 | 12 | 0.321 |

| Grade II | 12 | 60.17 ± 7.25 | 60 (14) | 51 - 72 | 0.937 | 12 | 0.466 |

| Grade III | 12 | 56.67 ± 12.34 | 58 (12) | 23 - 69 | 0.804 | 12 | 0.010 |

Nuclear SHH expression was predominantly negative across all study groups. No moderate or strong nuclear staining was observed in any specimen. All normal tissue samples (100%) demonstrated negative nuclear expression. Among tumor grades, negative nuclear expression was observed in 91.7% of grade I, 83.3% of grade II, and 91.7% of grade III specimens. Correspondingly, mild nuclear expression was present in 8.3% of grade I, 16.7% of grade II, and 8.3% of grade III specimens. Kruskal-Wallis analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in nuclear SHH expression among groups (χ2 = 2.14, P = 0.545; Table 3).

| Groups | Negative | Mild | Moderate | Strong |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal tissue | 12 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Grade I | 11 (91.7) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Grade II | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Grade III | 11 (91.7) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Kruskal-Wallis test: χ2 = 2.14, P = 0.545.

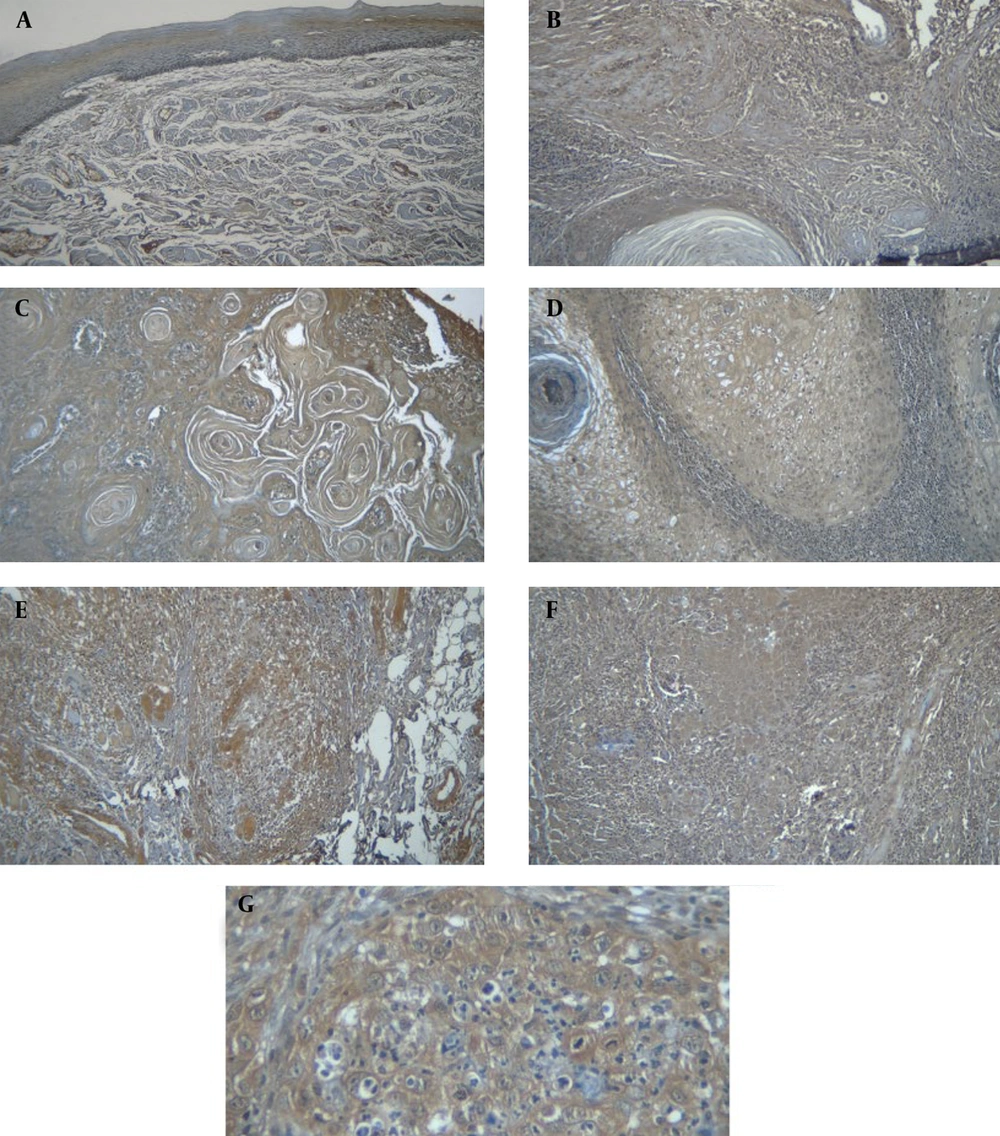

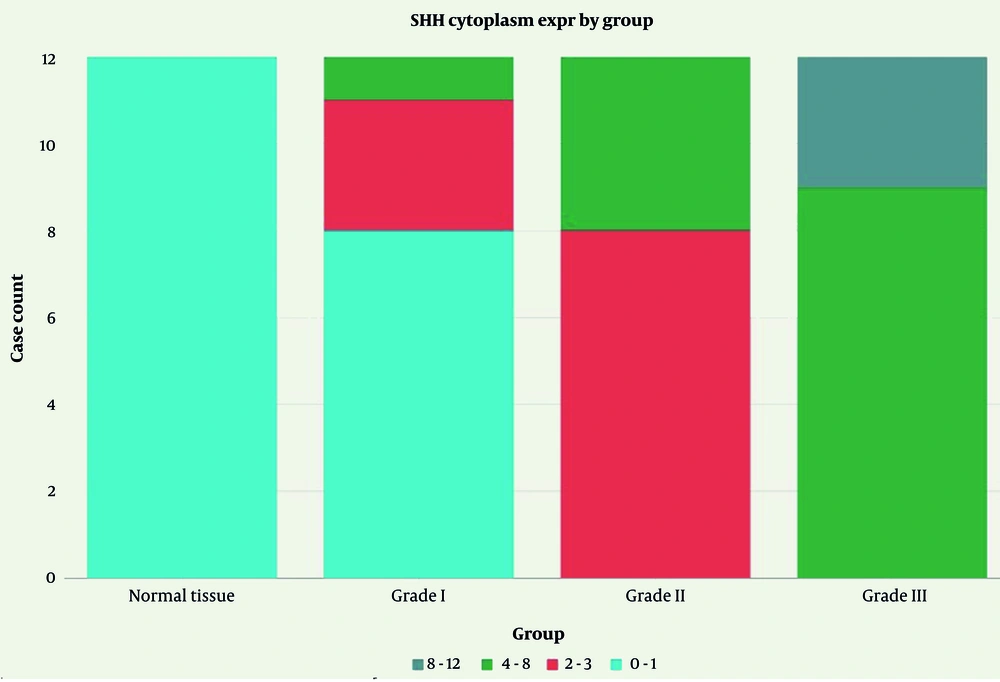

Cytoplasmic SHH expression demonstrated a distinct pattern, correlated with tumor grade progression. Normal tissue exhibited exclusively negative cytoplasmic staining (100%). Grade I TSCC showed 66.7% negative, 25.0% mild, and 8.3% moderate expression. Grade II TSCC demonstrated a shift towards higher expression levels with 66.7% mild and 33.3% moderate staining, with no negative cases. Grade III TSCC exhibited the highest expression intensity, with 75.0% moderate and 25.0% strong expression, and no negative or mild cases (Figure 1).

A, normal epithelium showing no expression of sonic hedgehog (SHH) in the cytoplasm and nucleolus (magnification 200×); B, negative SHH expression in tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC) I - (magnification 200×); C, positive SHH expression in TSCC I: Negative nuclear expression – mild cytoplasmic expression – magnification 200×); D, SHH expression in TSCC II: Negative nuclear expression – Mild cytoplasmic expression (magnification 200×); E, SHH expression in TSCC II: Negative nuclear expression – mild cytoplasmic expression (magnification 200×); F, SHH expression in TSCC III showing mild nuclear expression and strong cytoplasmic expression (magnification 200×); G, SHH expression in TSCC III demonstrating negative nuclear expression and moderate cytoplasmic expression (magnification 400×).

Statistical analysis revealed highly significant differences among groups (χ2 = 37.71, P < 0.001; Table 4). The following graph shows the distribution of SHH cytoplasmic expression levels across normal tissue and tumor grades (Figure 2).

| Groups | Negative | Mild | Moderate | Strong |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal tissue | 12 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Grade I | 8 (66.7) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Grade II | 0 (0.0) | 8 (66.7) | 4 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Grade III | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Kruskal-Wallis test: χ2 = 37.71, P < 0.001.

Dunn-Bonferroni post-hoc test demonstrated specific significant differences in cytoplasmic SHH expression. Normal tissue expression levels were not significantly different from grade I (P > 0.99) but were significantly lower than both grade II (P = 0.002) and III (P < 0.001). Grade I expression was numerically lower than grade II, though this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.076), but was significantly lower than grade III (P < 0.001). The difference between grade II and grade III expression levels was not statistically significant (P = 0.315, Table 5).

a Significance is P-value < 0.05.

Cytoplasmic SHH expression progressively increased with tumor grade advancement, with statistically significant differences observed between normal tissue and higher-grade tumors, and between low-grade and high-grade malignancies. Nuclear SHH expression remained consistently low across all groups without significant inter-group variation.

5. Discussion

The main finding of the present study was the significant association between increased cytoplasmic SHH expression and the histopathological grade of TSCC. Cytoplasmic SHH expression progressively increased from normal tissue through grade I to grades II and III, with statistically significant differences, particularly between early and advanced grades. However, nuclear SHH expression was almost consistently absent or minimally present across all groups and did not differ significantly with grade progression. These results suggest that cytoplasmic SHH protein levels could serve as a reliable biomarker for TSCC grading and potentially for disease progression.

This finding is consistent with and expands upon existing literature, highlighting the role of SHH signaling in OSCC biology. For instance, Cierpikowski et al. (15) demonstrated a similar pattern of increasing cytoplasmic SHH expression correlating with higher OSCC grades, although their study also reported significant nuclear expression increase, which was not identified in our study. The absence of significant nuclear staining in our samples may reflect differences in tissue sampling sites (our study exclusively involved tongue tissue) or variations in immunohistochemical protocols, emphasizing the importance of methodological standardization. Takabatake et al. (14) likewise observed increasing cytoplasmic SHH expression with advancing oral cancer grades, corroborating the significance of cytoplasmic localization in tumor progression. This study, with equal group sizes and rigorous inclusion of normal tongue tissue controls, further refines this association and emphasizes pairwise differences between lesion grades, highlighting the utility of cytoplasmic SHH as a discriminative marker.

Other studies focusing on head and neck malignancies have also reported elevated SHH expression linked to tumor progression and poorer prognosis. Chen et al. (19) found nearly universal moderate to strong cytoplasmic SHH staining in grade III OSCC samples, a result echoed here with 100% moderate to strong expression in grade III TSCC patients. Similarly, Kuroda et al. (17) emphasized the association of SHH expression with angiogenesis and malignancy aggressiveness in tongue SCC. Consistent with these, Srinath et al. (18) reported minimal nuclear but significant cytoplasmic SHH expression correlating with tumor grade, mirroring trends observed in our cohort. Variability in nuclear SHH findings across studies again highlights potential influences of tissue origin, sample size, and staining methodology, suggesting further investigation is warranted.

From a clinical perspective, the value of identifying a reliable marker such as SHH to complement or even improving upon existing subjective diagnostic tools stands to substantially impact early detection and personalized management of TSCC. Due to the poor prognosis and frequent late diagnosis associated with tongue cancer, which is the sixth most common malignancy globally, it is important to accurately stratify patients based on SHH expression. This could facilitate timely interventions and potentially improve survival outcomes. The increased expression of SHH in higher-grade tumors corresponds to its biological role in regulating cancer stem cell (CSC) proliferation and tumor aggression (20, 21), underscoring its relevance as both a diagnostic and therapeutic target. The significant upregulation of cytoplasmic SHH in TSCC highlights its role as a key oncogenic driver. This finding is reinforced by studies on natural compounds like Hedyotis diffusa willd on cervical cancer, which demonstrated that inhibiting proliferation, migration, and inducing apoptosis — processes regulated by SHH — can yield potent anti-tumor effects, validating SHH as a promising therapeutic target (22).

Nevertheless, our study has limitations that temper the generalizability of these conclusions. The sample size, although sufficient for detecting significant differences, remains modest, and larger multicenter investigations are needed to validate SHH’s diagnostic utility across diverse populations and tumor sub-sites. Additionally, mechanistic studies clarifying why nuclear SHH expression remains minimal in tongue lesions would elucidate the intracellular dynamics of the HH pathway in this malignancy. Future research should also explore the prognostic significance of SHH expression longitudinally and in relation to treatment response, ideally incorporating molecular analyses to complement immunohistochemical findings.

The limitation of the current study is the relatively small sample size, although justified by a post-hoc power analysis, which may limit the generalizability of our findings.

In conclusion, this study supports the role of cytoplasmic SHH expression as a marker closely associated with advancing TSCC grade, with potential applications in diagnostic stratification and as a therapeutic target. While our findings provide strong evidence for the association between SHH expression and tumor grade in our study, their applicability to broader populations should be validated in future multi-center studies with larger and more diverse sample sizes.