1. Background

Cancer remains one of the major causes of mortality worldwide, with several forms showing notably high prevalence. This contributes to a substantial public health challenge, as individuals often face late-stage diagnoses due to socioeconomic factors, which can exacerbate mortality rates (1, 2). Patients with cancer frequently experience emotional distress, anxiety, and depression. The stigma attached to certain cancers can lead to social isolation, impacting their relationships and community involvement. Caregivers also face significant emotional burdens, which can strain family dynamics (1, 3). The economic burden of cancer is substantial. Direct costs encompass medical treatment-related expenditures, whereas indirect costs stem from lost income due to illness or caregiving responsibilities. Families often struggle with these financial strains, which can lead to long-term economic challenges and exacerbate existing social inequalities (1, 4).

Given that cancer has caused major problems worldwide (5), awareness of its risk factors, symptoms, and screening programs remains insufficient in many populations. Public knowledge about cancer plays a pivotal role in promoting early detection and prevention, as individuals who are aware of their risk factors are more likely to adopt healthier behaviors and participate in screening programs. Enhancing public knowledge about various types of cancer can encourage individuals to adopt health-promoting behaviors, ultimately reducing cancer-related morbidity and mortality (6-8). Perception of risk factors for cancer, individuals can make lifestyle adjustments or undergo screening tests to detect cancer at an early stage. Successful early diagnosis of cancer heavily relies on individuals’ knowledge of its warning signs (9-11). Additionally, recognizing these warning signs and taking proactive measures, such as undergoing diagnostic tests, can prevent cancer from advancing to severe stages (9). Therefore, assessing public knowledge about cancer warning signs and identifying factors that influence this awareness are essential for guiding health initiatives aimed at controlling and preventing cancer at the community level (9, 12, 13).

Considering that the most common types of cancers are breast cancer (BC), with 2.2 million cases; colorectal cancer (CRC), with 1.9 million cases; prostate cancer (PC), with 1.4 million cases; and cervical cancer (CC), with 0.6 million cases worldwide (7). Studies have shown that a lack of awareness about cancer is associated with delayed diagnoses and poorer outcomes, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, especially in Iran, where public health education is often limited (14, 15).

Beyond public awareness, the successful implementation of screening programs also depends on efficient operational systems. In this regard, the development of integrated decision support information systems for CRC screening has been proposed as a promising approach to improve patient follow-up and participation (16). Additionally, CC, which is predominantly caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), is a prime example of a preventable cancer through vaccination and regular screening (17). This underscores the critical need for enhancing public knowledge about its risk factors and preventive methods.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to evaluate awareness levels of common cancers, examine knowledge about their prevention and treatment, and investigate the relationship between sociodemographic factors and cancer awareness among individuals aged 30 and older.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted as a population-based telephone survey of residents of Rasht (the capital of Guilan province in northern Iran) between January 28, 2017, and January 28, 2019 by the Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GLDRC).

Based on the sample size calculation using the Cochran’s formula for this population, with a 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96), 5% margin of error (d = 0.05), and an estimated proportion of 50% (P = 0.5), the initial sample size was determined to be 385 participants (13) and accounting for a non-response rate of 50%, the final sample size was 770 participants. Given that in this study we examined the knowledge and attitudes of four common cancers and considering the increased generalizability to the community, we increased the sample size.

The first telephone number from the Rasht telephone directory was selected randomly, and every 30th number was chosen to obtain a total of 1501 numbers. A total of 2304 individuals were contacted by telephone to assess eligibility and interest in the study. Of these, 803 (31.43%) declined to participate, a group which included 523 men and 280 women. After the individual answered the phone, they were asked how many residents in the household were over the age of 18. Subsequently, one person was randomly selected for an interview by appointment. If there was no response after attempting to reach the selected number three times, a previously or subsequently listed number would be chosen, continuing this process up to three different numbers until a respondent was found. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (IR.GUMS.REC.1395.373).

3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

First of all, the objectives of the survey were explained to people over 30 years old, the responders and persons telephoned were asked if they would be prepared to help research by answering some questions. Those who did not consent to answer the questions were excluded.

3.2. The Interview Processes

All interviews were conducted by two trained general practitioners. The objective of the survey was explained to the responders and the participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. The average duration of each interview was 20 minutes. One of the criteria for inclusion in our study was that participants needed to provide complete answers to all questions, and there were no refusals observed during the interview process. The questionnaire consisted of several sections. The first section gathered demographic and social information, including age, sex, marital status, educational level, family history of cancer, tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and Body Mass Index (BMI). The second part of the questionnaire evaluated participants’ knowledge across four domains. Cancer symptom awareness was assessed using ten items (including the presence of a mass in any part of the body, abnormal bleeding, vague pain, digestive problems, difficulty swallowing, changes in the shape of moles, alterations in urinary or bowel habits, weight loss, hoarseness/voice change/persistent cough, and wounds that do not heal for more than three weeks). General risk factor knowledge was measured through twelve items (smoking, alcohol use, opium consumption, genetics, radiation exposure, viral/bacterial infections, obesity, industrial pollution, air pollution, stress, mobile phone use, and lack of physical activity). Nutritional risk factors were assessed using nine items (high-fat foods, artificial sweeteners, grilled meat, hormone-treated meat or poultry, processed meats such as sausages, salt and pickles, canned foods, coffee, and fruit and vegetable intake). Finally, knowledge of cancer screening was evaluated with seven items [mammography, breast self-examination, Pap test, fecal occult blood test, blood tests, colonoscopy, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing].

The range of scores was between 0 and 1, in which a score lower than 0.18 for BC, 0.06 for CC, 0.62 for CRC, and 0.05 for PC was considered a lower than average level of awareness. Scores above these thresholds were considered to reflect above-average awareness for each respective cancer.

The results were presented based on the accuracy of responses to knowledge questions, both above and below the mean. To ensure validity, the study employed the Content Validity Index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR) for assessing content validity. Regarding the CVI, all questions across three sections demonstrated simplicity, clarity, and relevance scores exceeding 0.7, while the CVR for all questions was also above 0.7. To evaluate the scientific reliability of the questionnaire, it was divided into sections, and the correlation coefficient was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding a value of 0.8.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The data were reported by number, percentage, and mean ± standard deviation. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to check the normality of the data, which were evaluated using Fisher’s exact and Pearson chi-squared tests. Regression was applied to report the association between variables. The leveled score was calculated on a scale of 0% - 100%, based on which a score of less than 50% was considered poor awareness, 50% - 75% was considered average, and 75% or higher was considered a good level of awareness. Statistical analysis was done with SPSS for Windows, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and plots were depicted using GraphPad Prism, Version 8.0.1 (GraphPad Prism Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

A total of 1,501 individuals participated in the study. Most participants (1,051; 70.1%) were younger than 50 years, and the majority were married (1,108; 73.8%). In addition, 655 participants (43.7%) had a BMI between 19 and 25, 524 (34.9%) had a university-level education, 1,241 (82.7%) were employed, and 938 (62.5%) resided in urban areas (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 750 (50) |

| Female | 751 (50) |

| Age | |

| < 50 | 1052 (70.1) |

| 50 - 60 | 292 (19.5) |

| ≥ 60 | 157 (10.5) |

| Material status | |

| Single | 393 (26.2) |

| Married | 1108 (73.8) |

| Job status | |

| Unemployed | 260 (17.3) |

| Employed | 1241 (82.7) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 48 (3.2) |

| Under diploma | 429 (28.6) |

| Diploma | 500 (33.3) |

| University | 524 (34.9) |

| Use of cigarettes | |

| Yes | 184 (12.3) |

| No | 1317 (87.7) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Yes | 101 (6.7) |

| No | 1400 (93.3) |

| Habitat | |

| Urban | 938 (62.5) |

| Rural | 563 (37.5) |

| BMI | |

| 19 - 25 | 655 (43.7) |

| 25 - 30 | 636 (42.4) |

| ≥ 30 | 210 (13.9) |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index.

Appendix 1, in the Supplementary File presents the awareness and correct response rates of male and female participants regarding the risk factors and signs/symptoms of cancer. The data were broken down by gender (751 females, 750 males; total n = 1501). The reported mean scores of awareness in general, nutritional risk factors, and signs/symptoms fields were 0.67 ± 0.25, 0.61 ± 0.25, and 0.59 ± 0.26, respectively. Approximately 573 (38.2%) participants, 492 (32.8%), and 446 (29.7%) demonstrated a good level of awareness in the areas of general risk factors, nutritional risk factors, and cancer signs/symptoms, respectively. According to the results, there was a statistically significant association between gender and awareness scores in the domains of general risk factors, nutritional risk factors, and signs/symptoms (P < 0.05). However, for specific symptoms — including problems with digestion, difficulty swallowing, and changes in urinary or bowel habits — awareness scores did not differ significantly between men and women (P > 0.05) (Appendix 1, in the Supplementary File).

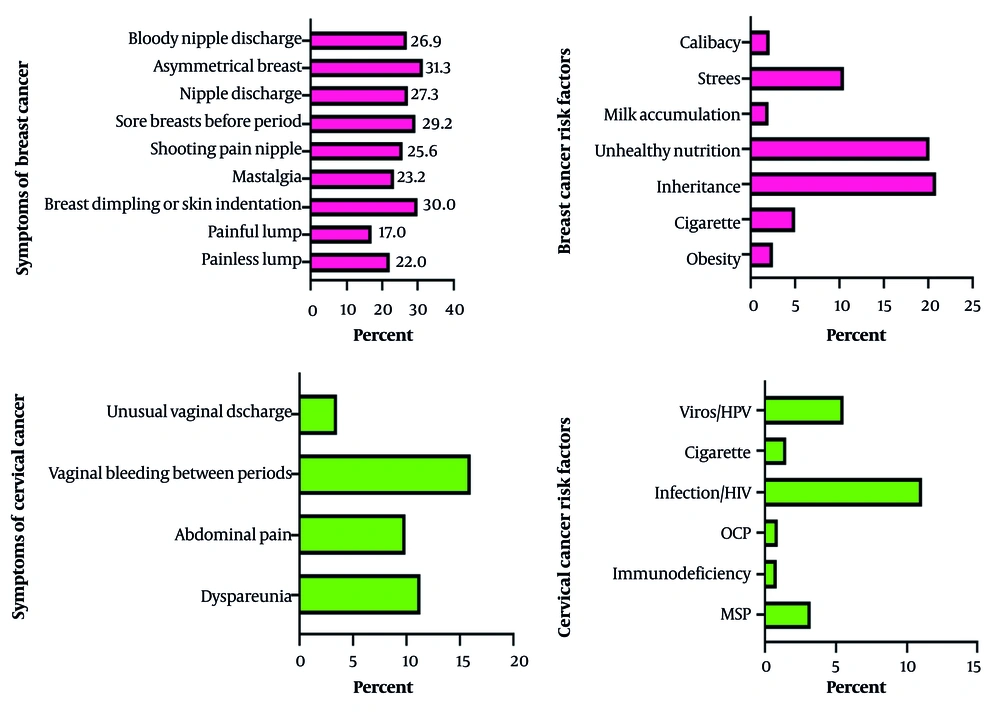

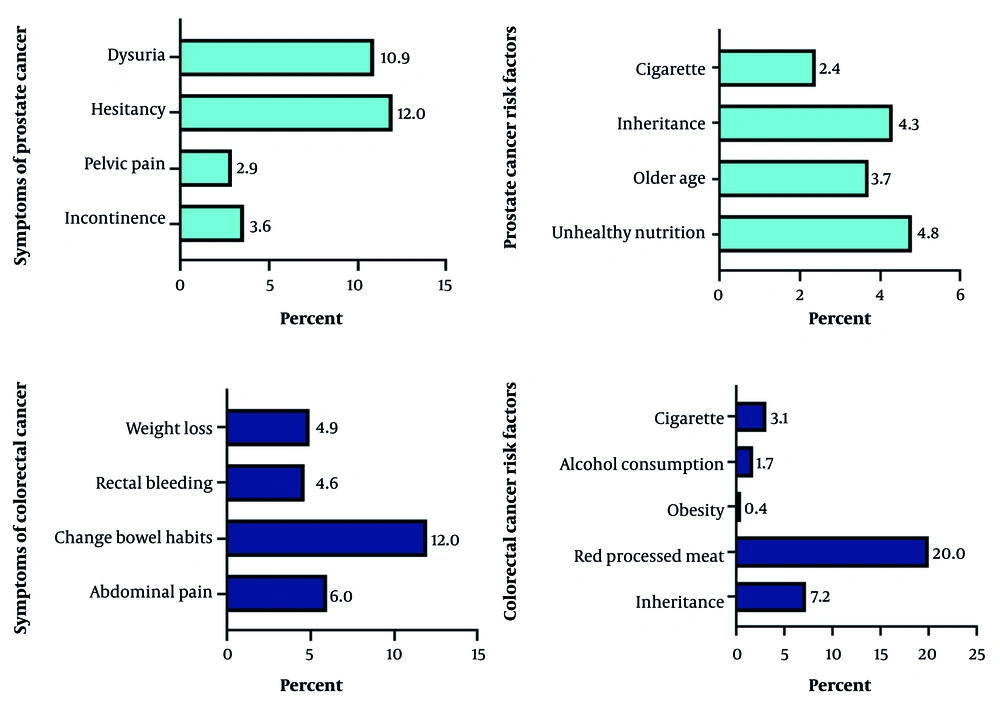

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the proportion of participants who accurately identified symptoms and risk factors related to cancers with established screening protocols. The most frequently recognized symptom for BC was breast asymmetry (31.3%), while for CC, it was intermenstrual vaginal bleeding (16%). For PC, urinary hesitancy was most commonly identified (12%), and for CRC, a change in bowel habits was noted by 12% of respondents. Regarding risk factors, unhealthy nutrition was most often identified for both BC (20.1%) and PC (4.8%); infection/HIV for CC (11.1%); and consumption of red processed meat for CRC (20%).

Proportion of female participants who correctly identified the symptoms and risk factors associated with BC and CC (Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; CC, cervical cancer; MSPs, multiple sex partners; OCP, oral contraceptive pills; HPV, human papillomavirus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus).

Appendix 2, in the Supplementary File compares awareness levels across various demographic and lifestyle variables, including age, marital status, employment, education, smoking, alcohol use, habitat (urban/rural), and BMI. Prostate cancer awareness increases significantly with age (P = 0.006), with individuals aged 50 - 60 being more likely to demonstrate above-average awareness. Employed participants had significantly higher awareness of cervical (P = 0.01) and CRC (P = 0.04) than unemployed participants. Higher education was strongly linked to greater awareness for all four cancers (P = 0.001 for each), with university-educated individuals having the highest awareness and illiterate participants the lowest. Additionally, participants with a BMI over 30 showed significantly higher awareness of colorectal (P = 0.01) (Appendix 2, in the Supplementary File).

Appendix 3, in the Supplementary File indicates the correct knowledge responses regarding common cancer screenings based on participants’ habitats. The study found that rural participants had significantly higher awareness and correct response rates for breast, cervical, and PC screening compared to urban participants. Specifically, rural residents outperformed urban ones in BC (29.1% vs. 20.9%, P = 0.014), CC (52.1% vs. 36.8%, P < 0.001), and PC screening (17.3% vs. 9.5%, P = 0.002). However, there were no significant differences between rural and urban participants in awareness of CRC screening methods (Appendix 3, in the Supplementary File).

5. Discussion

Understanding and recognizing public awareness for screenable cancers may provide valuable information for policy decisions for prevention, early diagnosis and improvement of survival. The high morbidity and mortality rates related to cancers are due to a lack of awareness, diagnosis at a more advanced stage, and socioeconomic barriers that limit access to better healthcare protocols. Globally, a substantial body of evidence indicates that knowledge of cancers is limited in many countries. The evidence suggests that nonconformity of proper health behaviors is inevitable in every society, and individuals and communities need proper health education to understand the right lifestyle and its application to prevent disorders (9, 13, 18-20). A critical issue in screening is the credibility of the medical community and the public’s trust in prevention, early diagnosis, and screening methods, which should be promoted through comprehensive and accurate information. This study aimed to assess the level of awareness regarding screenable cancers among the population in northern Iran.

In the present study, about 38.2%, 32.8%, and 29.7% of participants had a good level of awareness in general risk factors, nutritional risk factors, and signs/symptoms fields, respectively. Low reported awareness about cancer among other countries was consistent with findings that reflect a low level of awareness about the apparent importance of cancer, despite a high level of concern for the importance of cancer prevention (12, 19, 21, 22).

In the present study, PC awareness significantly increased with age, especially among those aged 50 - 60. Numerous studies have demonstrated that both the awareness and incidence of PC increase with advancing age, especially after the age of 50. According to the American Cancer Society and similar organizations, the likelihood of developing PC and consequently, awareness of the disease-grows significantly beyond this age, with most diagnoses occurring in men over 60. Recent publications also point to a growing incidence and heightened awareness among men aged 50 to 55, leading experts to advocate for routine screening within this age group to enhance early detection and outcomes (23, 24).

In the present study, employed and university-educated participants had significantly higher awareness of all cancer types, while illiterate and unemployed individuals had the lowest awareness. These results are aligned with previous research showing that higher education and employment status are strong predictors of cancer awareness and screening participation (12, 25-28). Additionally, higher BMI was associated with better awareness of CRC. The link between elevated BMI and CRC awareness is less frequently reported, though some studies suggest that individuals with obesity may be more engaged with health services and thus more exposed to educational messages (29, 30).

Early detection of cancerous and precancerous lesions can significantly improve outcomes and prognosis, allowing patients to enjoy an everyday life with limited complications of cancer and its treatment. Early-stage cancer treatment not only improves patients’ quality of life but also is also associated with lower financial costs, fewer side effects, and reduced risk of physical defects and deformities (28). In this regard, the findings of this study showed that rural participants had significantly higher awareness and correct response rates for breast, cervical, and PC screening compared to urban participants. Specifically, rural residents outperformed urban ones in BC (29.1% vs. 20.9%, P = 0.014), CC (52.1% vs. 36.8%, P < 0.001), and PC screening (17.3% vs. 9.5%, P = 0.002). However, there were no significant differences between rural and urban participants in awareness of CRC screening methods. It seems that higher awareness and correct response rates among rural participants may result from stronger primary healthcare infrastructure, targeted community health interventions, effective health communication, and reliance on public health services in rural areas. Local context and recent public health efforts likely play a significant role in these differences

5.1. Conclusions

This study revealed that overall awareness of cancer risk factors and symptoms among participants was moderate, with less than 40% achieving above-average scores in general, nutritional, and symptom-related knowledge. Significant differences in awareness were observed across demographic and lifestyle factors. Females, employed individuals, and those with higher education levels consistently demonstrated greater awareness of cancer risk factors and symptoms. Prostate cancer awareness increased with age, while higher BMI was associated with better awareness of CRC. Notably, rural participants showed significantly higher awareness and correct response rates for breast, cervical, and PC screening compared to their urban counterparts, although no such difference was found for CRC screening. These findings highlight the need for targeted educational interventions, especially among men, the unemployed, those with lower educational attainment, and urban residents, to improve cancer awareness and promote early detection and prevention.

5.2. Limitations

This study has several limitations. Its cross-sectional nature precludes causal conclusions. The telephone-based sampling method may have excluded households without landlines, potentially leading to selection bias. Furthermore, the overrepresentation of highly educated participants may affect the generalizability of the results to less-educated groups. Nevertheless, the use of a large, randomly selected sample and a validated instrument supports the applicability of our findings to similar populations in Northern Iran and other regions with comparable healthcare infrastructures.