1. Background

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is a major and chronic public health concern; it is defined as the intentional and direct injury to body tissues by plunging, burning, or beating oneself without suicidal intent and in opposition to societal norms (1). In various studies, different definitions of NSSI have been provided, leading to varying prevalence rates reported by these studies (2). A review study conducted across six geographical regions, including Asia, Canada, Australia, Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States, showed that the prevalence of NSSI increased over 19 years, ranging from 1.5% to 54.8% (3). A study on runaway adolescents in the United States also established a strong association between homelessness and self-injurious behaviors (4). The prevalence of self-harm among street children and welfare institution children is reportedly very high, which may be due to several psychosocial factors. These adolescents, in a state of victimization from abuse, neglect, and trauma, utilize self-injury as a coping behavior for emotional pain (5, 6). The prevalence of NSSI among American youth has been reported as 17.2%, and among Europeans, it is 20.1%. This behavior is not limited to Western countries and is also prevalent in Asian countries (3, 7, 8). Studies conducted in Japan, India, and Turkey have reported the prevalence of NSSI to be 10%, 31.2%, and 28.5%, respectively (9, 10). Additionally, a study in China showed that the prevalence of NSSI was 28.9%, with women being more affected than men (11). In 2024, a study found that the lifetime prevalence of NSSI among Iranian students and university students was 24.4% (21.4% among high school students compared to 29.3% among university students) (7). One such study in Mashhad reported that 59.2% of the street children showed self-harming behavior, with the most common methods being hitting at 26.5% and cutting at 21.4% (5).

Family abuse, social isolation, and mental disorders are other important factors that explain self-harm among street children. Parental loss, conflict, victimization through sexual and physical abuse, and a family history of self-harm increase the risk for self-injurious behavior (5, 12). Indeed, one study from the Greater Accra region in Ghana determined that the lifetime prevalence of self-harm was 20.2%, the 12-month prevalence was 16.6%, and the 1-month point prevalence was 3.1% among school adolescents and street youth; of these, 54.5% were cases classified as NSSI, while self-poisoning was reported at 16.2%. Furthermore, 26% used more than one method. Methods of self-injury were most frequently cutting at 38.7%, and of self-poisoning, alcohol was used by 39.2% and drugs by 27.7% of attempters (12). In a second study, 397 adolescents living in youth welfare and juvenile justice group homes experienced occasional NSSI by 21.9% of participants and repetitive NSSI by 18.4%. Out of these adolescents, 85.6% had mental health disorders, and in both genders, NSSI was comorbid with major depression, behavioral disorders, and substance use. Boys who engaged in NSSI were at a particularly high risk of suicide (13). In another study on adolescents conducted from social assistance facilities, it was pointed out that 80.3% of the participants in the survey practiced self-injury, and the most common objects used for this purpose were sharp objects (14). In a separate sample of opioid users, 25% demonstrated self-injury behaviors (15). Major risk factors for self-injurious behaviors include childhood abuse and borderline personality disorder. For example, in one investigation, it was determined that 29% of alcohol-dependent males exhibited self-harm, and childhood abuse was found to be one of the significant predictors (16).

The prevalence of NSSI varies across different populations. Global studies have shown that the prevalence of NSSI among adolescents ranges from 22.0% to 27.6% across different countries (1, 17). In contrast, among patients with eating disorders, the prevalence is higher, reaching 27.3% (18). Additionally, recent research has highlighted that NSSI is most prevalent in individuals with psychological issues such as depression and anxiety, as well as those in higher-risk social environments (19). Although NSSI is clinically significant, very little is currently known about its epidemiology, particularly within high-risk groups (20). The NSSI is a serious mental health issue that is associated with various physical, psychological, and social complications (7). This behavior is often more prevalent in high-risk populations and can indicate deeper vulnerabilities in the mental health of these individuals. Therefore, despite increasing global awareness of this issue, there is a lack of sufficient and comprehensive information about the prevalence of NSSI in high-risk populations in Iran. Therefore, conducting a systematic study and meta-analysis that provides a more accurate picture of the prevalence of NSSI in these groups seems necessary.

2. Objectives

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to identify patterns and prevalence of NSSI in high-risk populations in Iran to provide policymakers and mental health professionals with the opportunity to design effective and targeted interventions to prevent and manage this behavior.

3. Materials and Methods

This study has been carried out as a systematic review and meta-analysis to gauge the prevalence of self-harm in high-risk populations within Iran. The reporting of this manuscript has been performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (21).

3.1. Search Strategy

A scoping search of international electronic databases was conducted on Scopus, PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane, and PsycINFO. In addition, IranDoc, Magiran, and SID national databases were searched. This study imposed no restrictions on the starting date of the search across databases. All articles published from the inception of each database up to June 2024 were reviewed. In addition, a search in Google Scholar was conducted to screen as yet unpublished or grey literature. The search terms contained the following MeSH terms: Prevalence, Epidemiology, Iran, Self-injurious Behavior, Self-mutilation, and NSSI (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File). After that, the reference lists of all retrieved articles were reviewed. Data were imported into EndNote X7, after which duplicates were removed, and two researchers reviewed the articles independently.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

All cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort studies related to self-harm in high-risk populations conducted in Iran were included, regardless of the publication year. The study population consisted of both men and women, and all studies were required to report prevalence data on self-harm in high-risk groups. Case reports, case series, reviews, and meta-analyses were excluded. Studies without sample sizes were excluded from the meta-analysis. It is important to note that, as suicide attempts are distinct from NSSI (22, 23), we excluded studies that categorized suicide attempts as NSSI to focus specifically on the pure prevalence of NSSI. In this regard, studies that utilized questionnaires including a question about suicide attempts [e.g., Self-injury Survey, Deliberate Self-harm Inventory (DSHI)], but did not report the frequency of individuals responding to the questionnaire, were excluded from our study. Also, when question details were available, we included the studies by removing the data related to suicide attempts, ensuring that only NSSI data were analyzed. This methodological approach allowed us to focus exclusively on the prevalence of NSSI, avoiding any overlap with suicidal behaviors in our study. It is important to note that the definition of 'high-risk population' in this study is based on specific groups identified in the included studies. These groups include individuals who are homeless or living in shelters, those who have experienced sexual abuse, divorced individuals, people with substance use disorders, hospitalized patients, and individuals who have undergone psychological trauma. Such populations are at an elevated risk for self-harm, as highlighted in the study by McEvoy et al. (24). This distinction is essential as it allows for the precise reporting of self-harm prevalence within these high-risk groups.

For the purposes of this study, 'self-poisoning' refers specifically to intentional overdoses, where individuals deliberately ingest harmful substances or drugs to cause self-harm, without suicidal intent. Accidental ingestion of substances was excluded from this definition. Studies reporting Nonfatal Intentional Self-poisonings were included, while studies that did not specify whether the self-poisoning was intentional or accidental were reviewed based on available study details, and decisions were made accordingly (25). According to the Vermont Department of Health (2023) (26), intentional self-poisoning, which includes ingesting substances such as drugs, chemicals, or gases with the intent to harm oneself, may not necessarily be a suicide attempt and is classified as intentional self-harm by poisoning or overdose. This conceptualization aligns with how the included studies defined self-poisoning as part of NSSI.

Also, in this study, self-inflicted skin problems, such as dermatitis artefacta, are defined as skin conditions caused by repetitive, often compulsive manipulation, commonly associated with psychological distress. These behaviors differ from classic NSSI, like cutting, which involves deliberate self-injury to alleviate emotional pain without suicidal intent. Additionally, self-immolation is a rare suicide attempt using flammable substances, whereas self-inflicted burns involve the use of chemicals or heated objects to harm the skin, but without suicidal intent, making them distinct from self-immolation (27, 28).

In the included studies, NSSI intent was primarily verified through clinical interviews with trained mental health professionals, who directly asked individuals about their motivations for self-injury. In some studies, self-report questionnaires were also used to assess participants' reasons for the behavior. These methods ensured that only NSSI cases were included in the analysis.

3.3. Quality Appraisal

Article quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). This tool includes three parts: A selection part (4 questions), a comparability part (1 question), and an outcome part (3 questions). A final score is divided into three categories: Good quality (three or four stars in selection, one or two stars in comparability, and two or three stars in outcome); fair quality (2 stars in selection, one or two stars in comparability, and two or three stars in outcome/exposure); and poor quality (0 or 1 stars in selection, 0 stars in comparability, or 0 or 1 stars in outcome/exposure) (29). Appendix 2 in Supplementary File presents the qualitative assessment results.

3.4. Quality Assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. This tool consists of three sections: Selection (4 questions), comparability (1 question), and outcome (3 questions). Studies were categorized as good, fair, or poor based on the total score (29).

3.5. Study Selection

Two researchers independently performed the initial screening of studies, data extraction, and quality control assessments. If the reviewers disagreed, the team leader made the final decision regarding inclusion.

3.6. Data Abstraction Form

A pre-prepared checklist was used to extract data from the final articles, including author name, year of publication, study period, sample size, study location (province and city), type of high-risk group, gender, average age, type of self-harm, tool used, and the prevalence of self-harm.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using STATA 17.0. A random-effects model was adopted to account for heterogeneity between studies. Cochran's Q test and Higgins' I2 test were conducted to assess heterogeneity (30, 31). The forest plots of effect size were presented. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the results. Subgroup analyses were conducted if there was statistical heterogeneity, indicated by a P-value of less than 0.05.

3.8. Publication Bias

Funnel plots and Egger's weighted regression test were used to determine publication bias (32, 33). A P-value of more than 0.05 was considered to indicate no evidence of publication bias.

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection

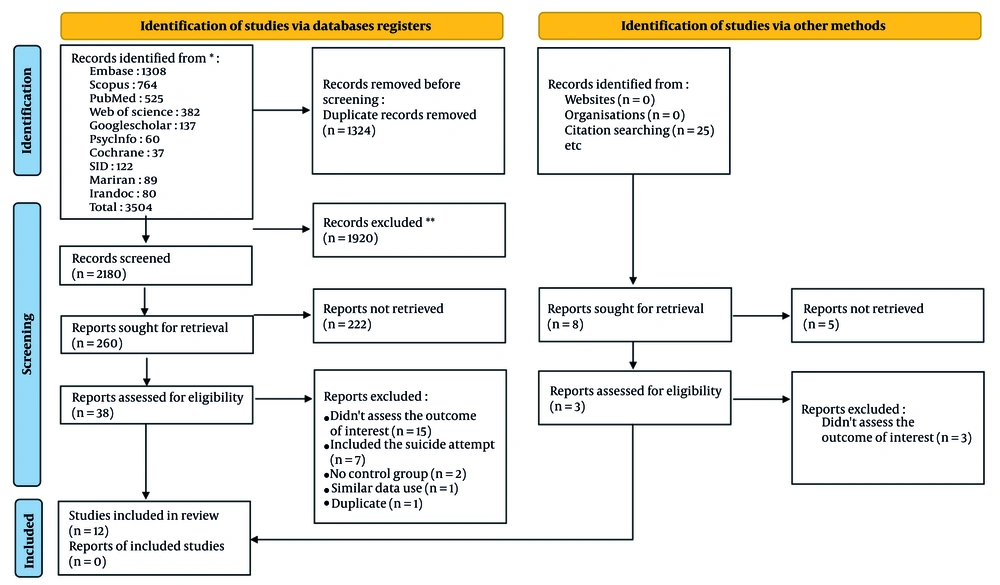

Searches in national and international databases resulted in the identification of 3,504 articles. After removing duplicates, 2,180 articles were screened for titles and abstracts; it was decided to proceed with a full-text review of 38 selected articles, and 12 were included. Reference lists of articles already included were also reviewed to capture any additional relevant studies. Figure 1 summarizes the process for selecting studies that were included in this review.

4.2. Characteristics of Studies

The period of the included studies covers 1993 to 2020. Twelve studies fulfilled the eligibility criteria and reported the prevalence of self-harm among high-risk populations, either overall or by gender, during the review period. Of these, 11 studies reported overall prevalence, while four focused on the prevalence among women and three among men. Descriptive information for these studies is presented in Table 1.

| Authors | Duration of Data Collection | Province (City) | Sex | Age (Mean ± SD) | Instrument for Self-injury Findings a | Kind of Self-injury | Total Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afshari et al. (2004) (36) | 1993 - 2000 | Khorasan Razavi (Mashhad) | All sex | 22.3 ± 14.3 | Researcher-checklist | NSSI | 7158 |

| Afzali et al. (2015) (34) | 2008 - 2013 | Hamadan (Hamadan) | All sex | 71.6 ± 5.1 | Researcher-checklist | NSSI | 418 |

| Zarei et al. (2011) (37) | 2011 - 2011 | Tehran (Tehran) | All sex | 33.1 ± 14.9 | Researcher-checklist | Self-inflicted skin problem a | 1321 |

| Babakhanian et al. (2012) (35) | 2009 - 2009 | Tehran (Tehran) | All sex | 36.5 ± 10.5 | Researcher-checklist | NSSI | 114 |

| Ekramzadeh et al. (2013) (38) | 2009 - 2009 | Fars (Shiraz) | All sex | 70.5 ± 7.5 | Standard instrument (HBS) | NSSI | 570 |

| Jarahi et al. (2021) (5) | 2020 - 2020 | Khorasan Razavi (Mashhad) | All sex | 13.8 ± 2.3 | Standard instrument (SHI) | NSSI | 98 |

| Khanipour et al. (2014) (39) | 2013 - 2013 | Tehran (Tehran) | All sex | 14.2 | Standard instrument (SHI) | NSSI | 238 |

| Mostafazadeh and Esmaeil (2017) (44) | 2014 - 2014 | Tehran (Tehran) | Female | 26.9 ± 9.1 | Researcher-checklist | NSSI | 300 |

| Shadnia et al. (2009) (40) | 2000 - 2007 | Tehran (Tehran) | All sex | 25.5 | Researcher-checklist | Self-poisoning | 471 |

| Shokrzadeh et al. (2011) (41) | 2008 - 2015 | Gorgan (Gorgan) | All sex | 25.2 ± 8.8 | Researcher-checklist | Self-poisoning | 800 |

| Taghaddosinejad et al. (2009) (42) | 2003 - 2006 | Khorasan Razavi (Ghouchan) | All sex | 23.6 ± 8.5 | Researcher-checklist | NSSI | 9874 |

| Talaie et al. (2018) (43) | 2016 - 2016 | Tehran (Tehran) | All sex | 36.8 ± 15.9 | Researcher-checklist | Self-inflicted skin problem a | 500 |

Abbreviations: NSSI, non-suicidal self-injury; HBS, Harmful Behaviors Scale; SHI, self-harm Inventory.

a Three studies that used a standardized checklist have been validated in Iranian populations. However, the remaining checklists, which were researcher-developed, have not been validated.

4.3. Quality Appraisal

As shown in Appendix 2 in Supplementary File, the findings of the appraisal of quality were satisfying. Based on the assessment of the relevant checklist, all included studies were considered of good quality.

4.4. Heterogeneity

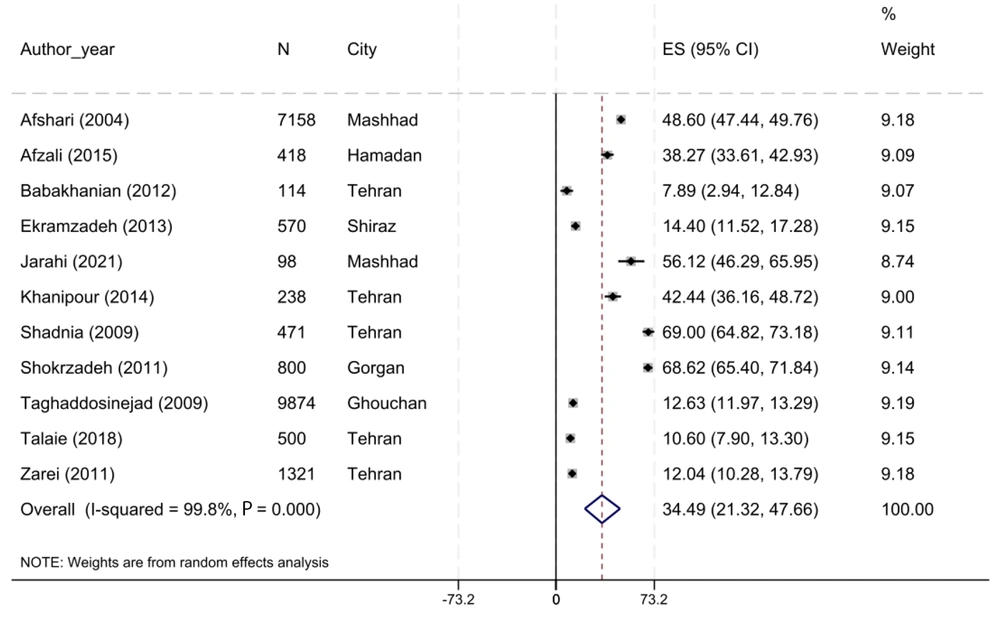

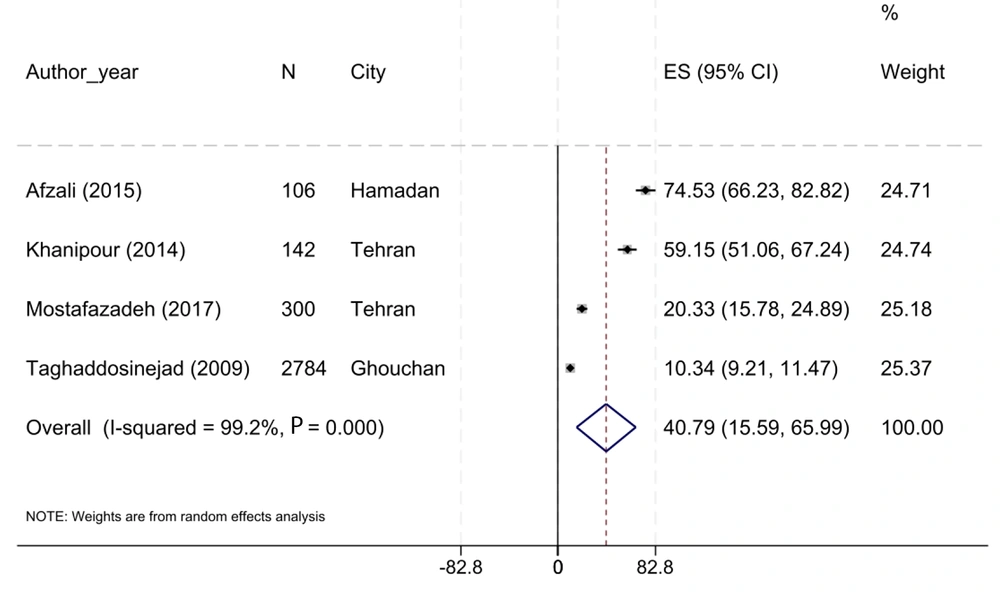

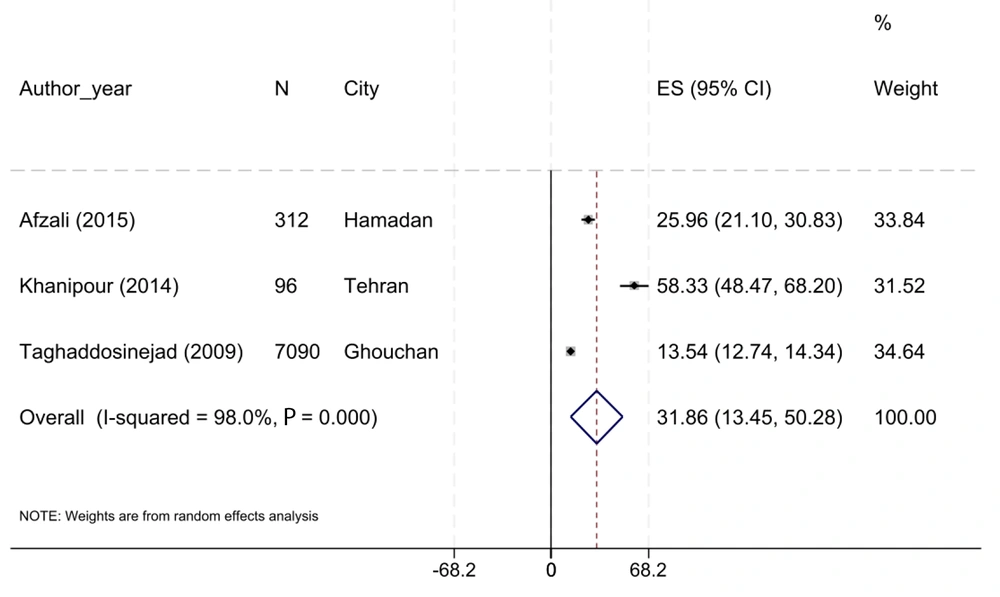

The results of the chi-squared tests and the I2 Index of these analyses indicate significant heterogeneity among the studies. Because the overall prevalence for the high-risk populations showed significant heterogeneity (I2 = 98.8%, P < 0.001), as did the prevalence for males (I2 = 98.0%, P < 0.001) and females (I2 = 99.2%, P < 0.001), a random-effects model was adopted for all analyses.

4.5. Results of Meta-Analysis

4.5.1. Prevalence of Self-harm in High-Risk Populations by Gender

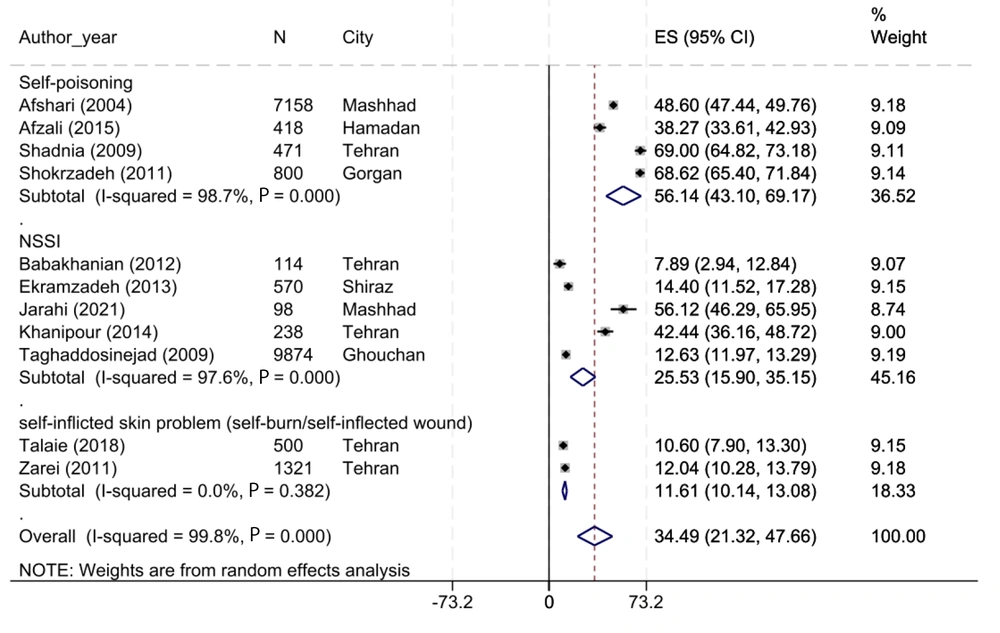

The articles were arranged first by the year of publication, and then the prevalence of self-harm in high-risk populations was analyzed by subgroups such as gender, provinces, and type of self-harm. In the final studies, a total of 11 reported the overall prevalence of self-harm in high-risk populations. By the random-effects model, the pooled prevalence of self-harm among high-risk populations was 34.49% (95% CI, 21.32 - 47.66; Figure 2). Moreover, the prevalence of self-harm in women was higher than that of men [40.79% (95% CI: 15.59 - 65.99) vs. 31.86% (95% CI: 13.45 - 50.28), respectively; Figures 3 and 4].

4.5.2. Subgroup Meta-Analysis of Self-harm Prevalence by Province

The prevalence of self-harm in high-risk populations by province showed that Tehran (5 studies) had a lower prevalence of NSSI than Khorasan Razavi [3 studies; 28.33% (95% CI, 8.40 - 48.26) vs. 38.90% (95% CI, 9.92 - 67.88), respectively]. The provinces of Hamedan, Fars, and Golestan had one study each, with their respective prevalences reported in the subsequent rankings (Table 2).

| Subgroups | N of Study | Effect Estimate (Prevalence Rate) | 95 % CI | I2 % | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | |||||

| Tehran | 5 | 28.33 | 8.40 - 48.26 | 99.4 | < 0.001 |

| Khorasan Razavi | 3 | 38.90 | 9.91 - 67.88 | 99.9 | < 0.001 |

| Hamadan | 1 | 38.27 | 33.61 - 42.93 | - | - |

| Fars | 1 | 14.40 | 11.51 - 17.28 | - | - |

| Golestan | 1 | 68.62 | 65.40 - 71.83 | - | - |

| Kind of self-injury | |||||

| NSSI | 5 | 25.53 | 15.90 - 35.15 | 97.6 | < 0.001 |

| Self-poisoning | 4 | 56.14 | 43.10 - 69.17 | 98.7 | < 0.001 |

| Self-inflicted skin problem | 2 | 11.61 | 10.14 - 13.08 | 0.00 | 0.382 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 3 | 31.86 | 13.45 - 50.28 | 98.0 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 4 | 40.79 | 15.59 - 65.99 | 99.2 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: NSSI, non-suicidal self-injury.

4.5.3. Subgroup Meta-Analysis of Self-harm Prevalence by the Type of Self-harm and Tools

Subgroup analysis showed that self-poisoning, with 4 studies, has a higher prevalence compared to NSSI (studies with no specific self-harm method) with 5 studies [56.14% (95% CI, 43.10 - 69.17) vs. 25.53% (95% CI, 15.90 - 35.15), respectively]. Additionally, self-inflicted skin problems have a lower prevalence compared to NSSI with 5 studies [11.61% (95% CI, 10.14 - 13.08) vs. 25.53% (95% CI, 15.90 - 35.15), respectively; Figure 5]. Also, NSSI prevalence based on tools revealed that studies using validated tools (3 studies) have a higher prevalence compared to studies using researcher tools [56.14% (95% CI, 43.10 - 69.17) vs. 25.53% (95% CI, 15.90 - 35.15), respectively; Appendix 3 in Supplementary File].

Subgroup meta-analysis of the self-injury prevalence in the high-risk population based on Kind of Self injury: 'Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)' refers to studies that did not report self-immolation or self-poisoning separately and only reported self-injury as a general category. Also, for the purposes of this study, 'self-poisoning' refers to intentional overdoses, where individuals deliberately ingest harmful substances or drugs to cause self-harm, without suicidal intent (5, 34-43).

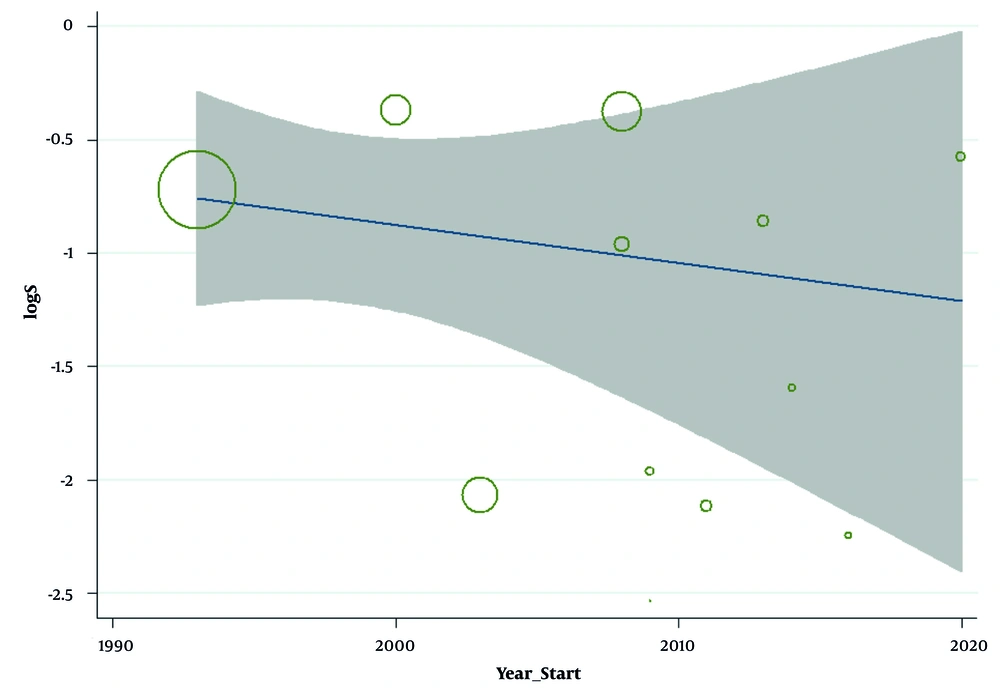

4.6. Meta-Regression of Non-suicidal Self-injury Prevalence-based on the Study Years

This study demonstrated a non-significant decrease in the prevalence of NSSI with an increase in study years (Reg Coef = -0.02, 95% CI: -0.09 to 0.04, P = 0.475; Figure 6). Also, there is a non-significant decrease in the prevalence of NSSI with an increase in age-mean (Reg Coef = -0.44, 95% CI: -1.24 to 0.37, P = 0.252; Appendix 4 in Supplementary File).

4.7. Publication Bias

Finally, we constructed funnel plots to explore publication bias in the prevalence estimates of self-harm among the high-risk population. The Egger's test result did not confirm evidence of publication bias (bias for total: -8.54, 95% CI = -27.18 to 10.09; P = 0.327; Appendix 5 in Supplementary File).

4.8. Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis showed that the proportion did not change after excluding any individual study, and the results remained statistically significant (Appendix 6 in Supplementary File).

5. Discussion

These findings from the meta-analysis show that self-harm is a highly prevalent behavior in high-risk populations. The overall estimated prevalence of 34.49% suggests that more than one-third of the high-risk populations had engaged in self-harming behaviors. There was a noted gender difference, where women had a higher prevalence at 40.79%, compared to men with 31.86%. In a study conducted by Afzali et al. on patients with acute poisoning, the prevalence of self-harm was reported to be 38.3% (34). Additionally, another study by Babakhanian et al. on patients with poisoning reported a prevalence of 7.9% (35). Our study reports a self-harm prevalence of 34.49%, which is higher than some of the initial studies and lower than others. The differences in the findings between studies can be attributed to variations in the study designs and the populations examined. Furthermore, surveys from the United States reported self-harm prevalence ranging from 7 - 37% among studied participants (45). A study in Ghana found lifetime self-injury prevalence at 20.2%, with 16.6% reporting past-year behaviors and 3.1% within the last month (12). People in group homes for youth welfare and juvenile justice reported occasional NSSI at 21.9% and repetitive NSSI at 18.4% (13), with differences possibly due to age variations in participants. A study conducted in Iran found that although women are more likely to experience NSSI, there was no significant difference in the prevalence and incidence of self-harm based on gender in their study (2). In contrast, Wang et al. reported that women are more susceptible to NSSI behaviors compared to their male counterparts (46). In line with this study, a school-based study in Norway (2002 - 2018) showed an increase in adolescent self-harm from 4% to 16%, with higher rates among girls than boys (47). Similarly, a population-based cohort study in Australia found an 8% prevalence of self-harm among 14 - 15-year-old students, with more girls (10%) reporting self-harm than boys (6%) (48). A UK cohort study in 2017 also noted higher self-harm prevalence among girls aged 10 - 19, with a sharp rise in 13 - 16-year-old girls between 2011 and 2014. These gender differences likely arise from psychological, social, and biological factors, warranting further research (49). In a meta-analysis that included a substantial number of studies with diverse and unbiased demographic samples, strong evidence indicated that women engage in NSSI more frequently than men. The study also highlighted that NSSI behaviors may vary between males and females. Additionally, the researchers suggested that hormonal differences between women and men could influence gender differences in the incidence of NSSI (50). Moreover, the higher prevalence of self-harm behaviors among women compared to men can be attributed to the greater incidence of psychological disorders, such as depression and anxiety, in this group. Notably, the prevalence of depression in women is approximately three times higher than in men (51, 52).

The present study also found variations in self-harm prevalence across provinces, with Tehran reporting 28.33% and Khorasan Razavi 38.90%. While the current study highlights regional variations in self-harm prevalence across provinces in Iran, these differences are influenced by a combination of socio-economic factors, cultural elements, and mental health infrastructure (24, 53, 54). Furthermore, socio-economic factors play a significant role in this context, with higher rates observed in rural areas and border provinces (55). The economic challenges faced by individuals in rural areas and border provinces, where higher rates of self-harm are observed, are significant factors contributing to this disparity (56). The interplay between economic stressors, access to mental health resources, and family dynamics plays a central role in shaping the mental health outcomes in these populations (57). Economic pressures, including the effects of sanctions, exacerbate mental health issues, leading to an increased vulnerability to self-harm behaviors, especially among adolescents and young adults who have limited access to care (58).

Cultural stigma, especially in the context of Iran and other Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) regions, significantly affects both the reporting and treatment of self-harm. In many MENA countries, including Iran, mental health issues and self-injury behaviors are often seen as a source of shame, leading to underreporting and a reluctance to seek help (59). This cultural stigma, coupled with a lack of understanding about mental health, results in an environment where individuals engaging in NSSI are less likely to disclose their behaviors and seek appropriate interventions (56). Moreover, family dynamics in MENA societies often discourage open discussion of mental health issues, further compounding the challenge of providing effective care. The stigma surrounding mental health and self-harm is deeply embedded in cultural norms, making it difficult for individuals to receive the support they need from their families or communities (57). Additionally, studies indicate that self-injury behaviors are often misunderstood and linked to attention-seeking or personal weakness, reinforcing the societal stigma and leading to further isolation of individuals who self-harm (60). In this context, ethnic and cultural differences also contribute to varying rates and risk factors for self-harm. For example, research has shown that stigma and socio-cultural factors are more pronounced in certain ethnic groups, leading to higher rates of self-injury, particularly among women in certain regions (61). In addition, religious and cultural coping mechanisms can serve as protective factors for some ethnic groups, highlighting the complex and multifaceted nature of self-harm behaviors across cultures (58).

In terms of specific behaviors, self-poisoning had the highest prevalence (56.14%) among self-harm types, indicating that poisoning is a common method in high-risk populations. Supporting this, a study in Egypt reported an increase in suicide attempts by poisoning between 2016 and 2020, with a prevalence of 26.10 per 100,000 people (62). In Ghana, non-poisonous self-harm accounted for 54.5% of cases, while self-poisoning made up 16.2%, with cutting being the most common form of self-injury (38.7%) (12). Another study found that adolescents in social care centers commonly used sharp objects for self-harm (14), differing from the findings of the present study, possibly due to limited access to toxic substances in specific populations.

5.1. Conclusions

The present study has established the high prevalence of self-harm within high-risk populations and varying prevalence according to gender, geographical region, and the kind of self-harming behavior. This points to an urgent call for effective interventions. Programs aimed at prevention and treatment should be planned in a targeted manner, considering differences to help reduce this behavior in society. These findings further emphasize the importance of considering gender-specific factors in the design and implementation of prevention and treatment programs.

5.2. Limitations

This study has several limitations. A major limitation is the heterogeneity among the included studies. This variation may arise from differences in methodology, study populations, definitions of variables, and methods used to measure self-injury. Such diversity makes it challenging to generalize the results accurately to all high-risk populations. Additionally, the use of different tools to assess NSSI led to the exclusion of some studies. One limitation of this study is the inclusion of studies that utilized non-validated tools, such as researcher-developed checklists, which may introduce variability in the measurement of self-injury behaviors. While these tools provided valuable insights, the lack of formal validation may affect the reliability and comparability of the findings across studies. These exclusions occurred when certain studies defined self-injury differently or included suicidal intent as part of self-injurious behaviors. This variation may have also influenced the study's findings.

Moreover, cultural and reporting biases are significant limitations that may have affected the results. Stigma surrounding self-injury in different cultures, particularly in regions like the MENA, likely contributed to underreporting of NSSI behaviors. In societies where mental health issues are often stigmatized, individuals may be less likely to seek help or disclose self-harm behaviors, leading to underrepresentation of the true prevalence of NSSI (such as in studies from Iran). These cultural biases can affect both the reporting of NSSI and the willingness of participants to engage in studies that address sensitive topics. Additionally, the variation in the willingness of participants from different cultural backgrounds to report NSSI may have introduced further inconsistencies in the data.

Another limitation is the limited access to specific study data, such as detailed age and medical history, which restricted the ability to analyze risk factors and subgroups more comprehensively. Without detailed demographic information, the ability to explore how factors like age, gender, and underlying medical conditions influence self-injury prevalence and severity is limited.