1. Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD), affected by the atherosclerotic pathologic process of the coronary vessels, is recognized as the leading cause of death worldwide (1). Atherosclerosis is a complex condition characterized by a series of interrelated processes that typically occur together, including irregular lipid levels, blood clot formation, platelet activation, vascular smooth muscle cell activation, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and alterations in extracellular matrix metabolism. Typically, atherosclerosis is the primary cause of CAD, which progresses gradually (2, 3).

Unmodifiable variables such as age, gender, blood pressure (BP), aberrant lipid metabolism, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease are linked to atherosclerosis and the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Nevertheless, some factors can be altered, such as lifestyle choices, smoking, dietary habits, and weight status, which can significantly influence the prevention or postponement of significant risks associated with CVD. However, dietary patterns are the primary focus of research on CVD. It is predicted that one in five early mortalities worldwide could be averted with an appropriate, balanced diet. Recently, there has been a growing focus on how specific eating habits affect the severity and progression of CAD (4).

Yet, defining an ideal, balanced diet remains somewhat ambiguous. There are differences in other nutritional requirements, including the use of whole grains versus refined grains and the forms of protein (plant-based vs. animal-based). However, most dietitians and experts agree that a higher intake of fruits and vegetables is necessary (5).

The dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet is recommended for individuals with high BP as it consists of food categories known to have BP-lowering effects (6). The DASH diet, in particular, places a strong emphasis on consuming vegetables, fruits, seafood, legumes, whole grains, nuts, lean meats, and dairy products. Moreover, it emphasizes limiting the consumption of sugar, salt, and saturated fats (7). The DASH diet has lower levels of dietary cholesterol, saturated fat, and total fat compared to conventional diets. Still, it also contains higher levels of dietary fiber, protein, calcium, potassium, and magnesium (8). In the first DASH diet clinical trial, both systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) decreased by 5.5 mmHg and 3.0 mmHg, respectively (9). The BP and other cardiovascular risk variables, such as blood sugar, lipid levels, obesity, and waist circumference, were successfully reduced by the DASH diet (6, 10). Therefore, it is predominantly suggested for individuals with high BP, although its beneficial impacts on heart health have also been studied with CAD (7). Additionally, further research on the DASH diet has demonstrated the advantages of this dietary approach in managing and preventing arterial hypertension (HTN), as well as in reducing the risk of heart failure, heart ischemia, stroke, and CVDs (9, 11).

2. Objectives

This comprehensive study aims to investigate the relationship between the DASH diet and the severity of CAD. Studying the role of nutrition in controlling CAD is crucial for both healthcare professionals and individuals seeking to enhance their heart health. By identifying the potential advantages of the DASH diet, we can expand our understanding and make evidence-based recommendations to help alleviate the burden of this common cardiovascular condition.

3. Methods

3.1. Statistical Population

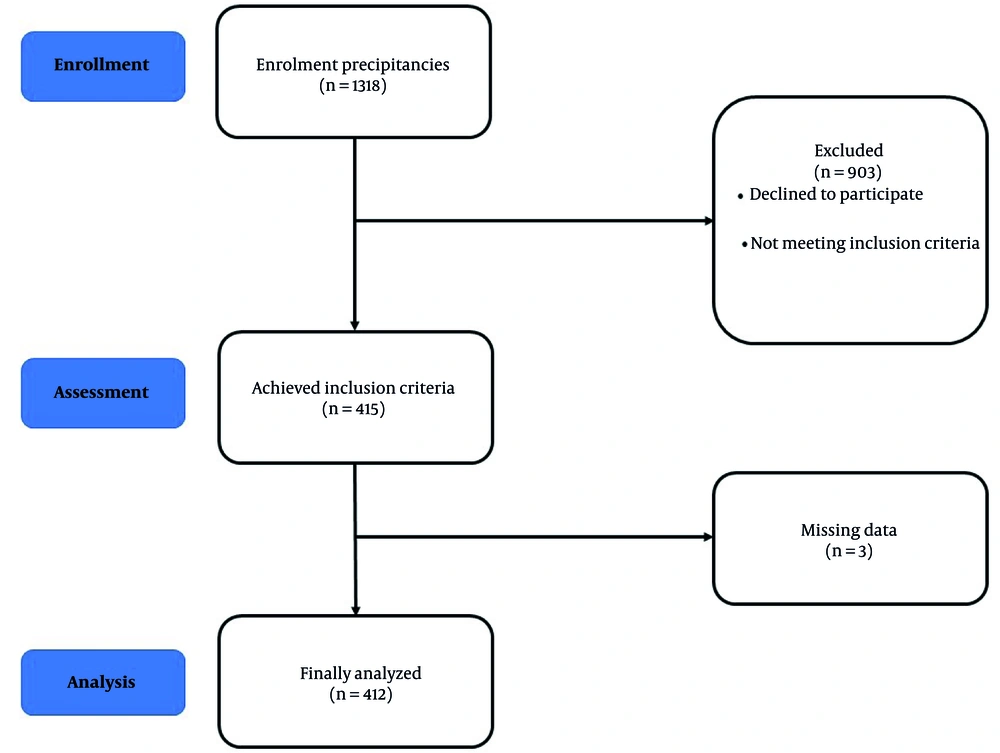

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Birjand from May 2019 to March 2020 as part of an extensive, multicenter study (I-PAD) on Iranian patients of diverse ethnicities. A total of 415 patients referred to the Razi Hospital Center for angiography were selected using a convenience sampling method. The inclusion criteria were age less than 70 years in women and less than 60 years in men, parental ethnicity homogeneity, and constriction of at least one vein greater than 75% (or left main greater than 50%). The exclusion criteria involved factors such as unclear or incomplete angiographic form data, unavailability of an angiographic report, and a history of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), balloon angioplasty, or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Patients with constriction in at least one vein over 75% were placed in the patient group.

In contrast, those with normal veins were placed in the normal group (Figure 1). The study protocol received approval from the ethics committee affiliated with Birjand University of Medical Sciences (IR.BUMS.REC.1397.313). Patients participated voluntarily and signed informed consent forms. Expert interviewers gathered the data through direct interviews and questionnaires (12).

3.2. Assessment of Demographic and Anthropometric Information

Initially, a trained nurse research assistant completed the patients' demographic forms. The form included details such as age, gender, ethnicity, religion, income status, employment status, marital status, education status, addiction status, history of alcohol and tobacco use, and any history of heart disease risk factors, including dyslipidemia (DLP), diabetes mellitus (DM), HTN, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), opium use, and CAD at an early age.

The anthropometric data questionnaire included measurements of weight, height, and waist circumference, taken according to established protocols. Weight measurements were conducted using a digital scale with a precision of 0.1 kg, with minimal clothing coverage, and without footwear. People's height was measured with an accuracy of 0.5 cm using tape measures in a standing position, next to a wall, and without shoes, with their shoulders in a normal position. The Body Mass Index (BMI) variable was calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the square of the height in meters, based on the weight and height measurements. Finally, the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was calculated by dividing the waist circumference by the hip circumference.

3.3. Assessment of Biochemical Information

Initially, the participant was seated and at rest for at least five minutes while their BP was taken using a calibrated sphygmomanometer. Using a cuff of the proper size, measurements were made on the upper arm at heart level. At one-minute intervals, two readings were taken, and the average was then analyzed. At 10 to 12 hours of fasting, 10 mL of blood was drawn in a fasting state (7 a.m.) and poured into test tubes (without anticoagulant). After 45 minutes of exposure to room temperature and clot formation, the blood was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 20 minutes. The serum samples were transferred into sterile microtubes and subsequently stored in a freezer at a temperature of -80 degrees Celsius until the start of the test. Commercial kits (Pars Azmun, Iran) and an auto-analyzer (Prestige 24i, Tokyo Boeki Ltd., Japan) were used to measure fasting blood sugar (FBS) and lipid profile, which includes total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL).

3.4. Assessment of Angiographic Information

The cardiologist accurately documented the outcome of the patient's coronary angiography. Patients who exhibited normal or near-normal angiographical results were classified as the control group. In contrast, those who experienced a seizure in one, two, or three veins were classified as the pathologic cases group.

3.5. Assessment of Nutritional Intake

The nutrition interviewer completed a 110-item, semi-quantitative Food Intake Questionnaire to assess the participants' food intake (13). The Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) provided the frequency in ten-option categories (‘seldom/never, once per month, 2 - 3 per month, once per week, 2 - 3 per week, 4 - 6 per week, 1 per day, 2 - 3 per day, 4 - 5 per day, and six or more per day). In addition, participants were asked to record the portion sizes of each food and beverage item. The frequency was converted to daily intake using household measurements, and the portion sizes were changed to grams. The proportion of each food item was converted to grams using the Home Scales Handbook. The Nutritionist 4 program was employed to assess the energy and nutrient intake. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire have been confirmed in Iran through prior research (12).

3.6. Assessment of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score

The dietary DASH score was measured using Fung's approach (14). The intake of each food group was calculated per 1,000 kcal to account for individual energy consumption. Participants were divided into five groups based on their dietary patterns. The intake of 8 specific food groups and nutrients, such as fruits, vegetables, nuts and legumes, whole grains, grain products, and low-fat dairy products (which are recommended in the DASH score), as well as sodium, sweetened beverages, and red meat and processed meat (which are discouraged in the DASH score), were adjusted for energy consumption. Those in the top quintiles of the five adequacy components scored five points, while those in the lowest quintiles scored at least one. Regarding the moderation component intakes, individuals from the lower quintiles of the intake distribution had higher scores (with quintile 1 receiving 5 points and quintile 5 receiving 1 point). Ultimately, the overall DASH score, which ranged from 8 to 40, was calculated by summing the scores of the eight components for both male and female participants (15).

3.7. Statistical Methods

A SPSS version 20 software program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. In the case of data that follows a normal distribution, it is represented as means ± SD. Participant characteristics were compared across the tertiles of energy-adjusted DASH score using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi-square statistics for categorical variables. In cases where the ANOVA indicated statistically significant differences (P < 0.05), Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied to identify specific group differences.

Using the distribution of the controls, the dietary DASH score was divided into three tertiles. Binary logistic regression was used to fit several models and evaluate the relationships between lipid profiles and DASH score tertiles. In the first model, age and sex were adjusted. Additionally, adjustments were made for DM, HTN, and DLP in the second model. In each examination, the lowest third of DASH scores was used as the comparison reference. The odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using multivariable logistic regression analysis to assess the relationship between lipid profiles and DASH scores. Statistical significance was defined as a P ≤ 0.05.

4. Results

The 412 participants, comprising 185 males and 227 females with an average age of 54.10 ± 7.70 years, were categorized into three groups based on their adherence to the DASH diet: T1 (low adherence), T2 (moderate adherence), and T3 (high adherence). There was no significant association found between the demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the participants, such as sex, age, DLP, DM, HTN, stroke, MI, and opium use, and their adherence to the first and third tertiles of the DASH diet (P > 0.05). The WHR was higher in individuals following the DASH diet in the first tertile than in the third tertile (P = 0.005). Moreover, individuals following the DASH diet in the lower tertile had a higher CAD rate than those following it in the higher tertile (P < 0.05; Table 1).

| Variables | DASH Diet | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (N = 149) | T2 (N = 129) | T3 (N = 134) | ||

| Sex (male) | 75 (50.3) | 52 (40.3) | 58 (43.3) | 0.221b |

| Age (y) | 53.26 ± 8.13 | 54.78 ± 7.64 | 54.40 ± 7.21 | 0.225 c |

| WHR (cm) | 118 (84.9) | 86 (69.4) | 106 (82.2) | 0.005 b |

| DLP | 57 (38.3) | 56 (43.4) | 48 (35.8) | 0.437 b |

| DM | 54 (36.2) | 49 (38) | 43 (32.1) | 0.587 b |

| HTN | 83 (55.7) | 76 (58.9) | 76 (56.7) | 0.861 b |

| Stroke | 24 (16.1) | 31 (24) | 25 (18.7) | 0.241 b |

| MI | 60 (40.3) | 49 (38) | 48 (35.8) | 0.743 b |

| Opium (current and former) | 43 (28.9) | 36 (27.9) | 29 (21.8) | 0.356 b |

| CAD | 83 (55.7) | 53 (41.1) | 62 (46.3) | 0.046 b |

Abbreviations: DASH, dietary approaches to stop hypertension; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio, DLP, dyslipidemia; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Chi-square test.

c ANOVA.

The LDL and cholesterol levels were lower in participants in the third DASH diet tertile compared to those in the first DASH diet tertile (89.14 ± 29.41 mg/dL vs. 92.07 ± 28.35 mg/dL, P = 0.049, and cholesterol 154.88 ± 41.31 mg/dL vs. 161.78 ± 44.66 mg/dL, P = 0.048). The DASH diet did not improve other blood lipid markers such as HDL, TG, and FBS (Table 2).

| Variables | DASH Diet | P-Value b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (N = 149) | T2 (N = 129) | T3 (N = 134) | ||

| HDL (mg/dL) | 45.83 ± 10.21 | 45.86 ± 11.09 | 45.33 ± 11.16 | 0.902 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 92.07 ± 28.35 | 97.84 ± 31.83 | 89.14 ± 29.41 | 0.049 c |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 161.78 ± 44.66 | 167.37 ± 40.82 | 154.88 ± 41.31 | 0.048 c |

| TG (mg/dL) | 142.97 ± 70.90 | 142.78 ± 81.26 | 128.32 ± 62.34 | 0.157 |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 113.72 ± 53.31 | 105.90 ± 35.73 | 115.40 ± 50.00 | 0.224 |

Abbreviations: DASH, dietary approaches to stop hypertension; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglyceride; FBS, fasting blood sugar.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b P-value from analysis of the variance (ANOVA) for group comparison.

c T1 - T3 P < 0.05.

After adjusting for all potential confounders, we found no significant association between the first and third tertiles of FBS and lipid profile, as well as the DASH dietary pattern (Table 3).

| Variables | DASH Diet | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | |||

| Crude | 1 | 1 [0.979 - 1.022] | 0.996 [0.974 - 1.018] |

| Model 1 | 1 | 0.993 [0.971 - 1.016] | 0.990 [0.968 - 1.013] |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1 [0.978 - 1.022] | 0.994 [0.972 - 1.017] |

| LDL (mg/dL) | |||

| Crude | 1 | 1.006 [0.998 - 1.014] | 0.997 [0.989 - 1.005] |

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.005 [0.997 - 1.013] | 0.995 [0.987 - 1.003] |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.006 [0.998 - 1.014] | 0.997 [0.989 - 1.005] |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | |||

| Crude | 1 | 1.003 [0.997 - 1.008] | 0.996 [0.990 - 1.002] |

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.002[0.996 - 1.007] | 0.994 [0.988 - 1] |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.003 [0.997 - 1.008] | 0.996 [0.990 - 1.002] |

| TG (mg/dL) | |||

| Crude | 1 | 1 [0.997 - 1.003] | 0.997 [0.993 - 1] |

| Model 1 | 1 | 1 [0.997 - 1.003] | 0.997 [0.994 - 1.001] |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1 [0.997 - 1.003] | 0.997 [0.994 - 1.001] |

| FBS (mg/dL) | |||

| Crude | 1 | 0.996 [0.991 - 1.002] | 1.001 [0.996 - 1.005] |

| Model 1 | 1 | 0.995 [0.990 - 1.001] | 1 [0.996 - 1.005] |

| Model 2 | 1 | 0.996 [0.990 - 1.001] | 1.001 [0.996 - 1.006] |

| LDL/HDL (mg/dL) | |||

| Crude | 1 | 1.258 [0.912 - 1.809] | 0.888 [0.624 - 1.265] |

| Model 1 | 1 | 1.288 [0.911 - 1.821] | 0.889 [0.622 - 1.271] |

| Model 2 | 1 | 1.276 [0.903 - 1.803] | 0.905 [0.634 - 1.294] |

Abbreviations: DASH, dietary approaches to stop hypertension; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglyceride; FBS, fasting blood sugar.

a Model 1: Adjust for age and sex; model 2: Adjust for DM, DLP, HTN; and tertile 1 was considered the reference group.

5. Discussion

In the present study, it was shown that strict adherence to the DASH diet could possibly reduce the severity of CAD more than low adherence. Our findings indicate a significant association between the highest DASH diet tertile and a decreased risk of CAD and WHR. In addition, high adherence to the DASH diet (in the last tertile) was associated with a lower risk of low serum LDL and cholesterol levels. Several studies have documented a correlation between adherence to the DASH diet and the likelihood of CVDs (16, 17). People with fewer CVD risk factors follow the DASH diet (18, 19). Several other studies have shown that incorporating a nutritious diet is associated with weight reduction and a decrease in obesity in some instances (20, 21). Additionally, several studies demonstrated the diet's positive effects on serum TG levels (22).

Our results align with prior research on adolescents, indicating that a more rigorous adherence to the DASH diet is associated with a reduced prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and its related factors, including high BP and a distribution of fat that is primarily visceral and abdominal (23). In another investigation involving adults with type 2 diabetes who adhered to the DASH diet for eight weeks, a higher level of compliance with this dietary pattern resulted in significant decreases in body weight and BP (24). These findings indicate that the DASH diet can effectively halt the establishment of cardiovascular risk factors, including overweight and BP.

Another study revealed that students adhering closely to the DASH diet consumed increased amounts of potassium, magnesium, fiber, and calcium. This was accompanied by a higher vegetable intake, fruits, legumes, nuts, dairy products, and whole grains (25). Similarly, Streppel et al. (26) suggested that the DASH diet's high potassium and magnesium contents could account for the diet's positive benefits on lipid profile and general metabolism. Conversely, the DASH diet's benefits on visceral fat accumulation and abdominal fat may be explained by consuming more fruits, vegetables, and legumes along with less saturated fat and increased monounsaturated fatty acid consumption.

Furthermore, Hall (27) suggested that a high intake of predominantly saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and non-esterified fatty acids could activate inflammatory pathways, raising levels of oxidative stress and promoting dysfunctional endothelial cells in these individuals. These findings suggest that these dietary components work together to benefit the DASH diet. Numerous flavonoids and antioxidants found in the fruits, vegetables, and other foods that the DASH diet emphasizes can help considerably lower indicators of inflammation and oxidative stress (28, 29), improve the function of endothelial cells, and therefore lower BP (30). Previous systematic studies have found that rigorously following the DASH diet can lower BP and total blood cholesterol and LDL levels (9, 31). Additionally, it has been shown to improve body weight, body fat, glycemic control (32), and serum markers of inflammation. These effects may reduce the risk of developing heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and some forms of cancer, all of which are connected to a shorter life expectancy (11). Nevertheless, further research is needed to understand the effects of the DASH diet on metabolic health (33).

Although the DASH diet study provides valuable insights into how the severity of CAD is affected, it is essential to acknowledge the study's limitations, strengths, and opportunities for further investigation. A wide range of possible confounders was evaluated in the current investigation. Sampling and statistical analysis were carried out with the highest level of quality control. Nevertheless, the research is constrained by self-reported dietary data, which is prone to errors and recall bias. Furthermore, as the current research methodology is cross-sectional, the results are not anticipated to demonstrate a clear causal relationship. Longer intervention studies are therefore necessary to have a more precise picture of the correlation between maternal food quality and the severity of CAD. The results of this kind of study can offer practical approaches to patient-centered nutrition therapy.

5.1. Conclusions

According to the findings, strict adherence to the DASH diet is likely to reduce the severity of CAD more than low adherence. The effects of the DASH diet on the severity of CAD are believed to result from a combination of various mechanisms. Potential factors include the diet's anti-inflammatory qualities, better lipid profiles, BP control, and generally balanced nutritional intake. Further investigation is necessary to clarify the complex biological processes involved, ultimately providing a more comprehensive understanding of how these dietary strategies can enhance cardiovascular health and well-being.