1. Context

Congenital heart diseases, recognized as one of the most common congenital defects in children, have profound impacts on the overall health and quality of life of affected individuals. In recent years, advancements in medical and surgical fields have significantly improved the treatment of these conditions. Despite these achievements, certain post-operative complications, such as post-operative fever, remain challenging and can lead to serious complications (1, 2). Post-operative fever following congenital heart surgery is identified as a significant clinical symptom, potentially arising from the body's inflammatory response to surgery or the onset of an infection. This condition can have long-term impacts on patient recovery and increase the demand for specialized care, making its detailed examination critically important (3, 4).

Numerous studies have indicated that the prevalence of post-operative fever in pediatric heart surgeries varies depending on surgical techniques and individual patient characteristics. Factors such as the duration of surgery, type of cardiac defect, and hospital environmental conditions play a crucial role in the occurrence of fever. Thus, a comprehensive and systematic approach to this issue could help identify precise patterns of influencing factors (5, 6). Identifying regional and demographic differences in the prevalence of post-operative fever can provide valuable insights for researchers and clinicians. Comparative studies across medical centers and regions can enhance therapeutic and management strategies to address this complication (7, 8).

The impact of pre- and post-operative care on reducing the prevalence of fever is another significant area of focus. Studies have shown that improving infection management protocols and adequately training medical teams can positively influence the reduction of fever incidence. These findings underscore the need for further research and implementation in this domain (9, 10). Additionally, a detailed investigation of the biological mechanisms associated with post-operative fever may help identify novel biomarkers. These biomarkers could effectively predict and prevent fever in children undergoing heart surgeries. Such approaches facilitate personalized therapeutic methods and can lead to better clinical outcomes (11, 12).

The influence of technological advancements and innovative surgical techniques in reducing the prevalence of post-operative fever is another notable topic. These developments, including the adoption of advanced equipment and minimally invasive surgical techniques, not only improve precision but also decrease the likelihood of post-operative complications (13, 14). Interdisciplinary studies that explore the psychological and social aspects of post-operative fever can complement biological investigations. Such research could provide a deeper understanding of the needs of patients and their families, enabling the creation of more comprehensive care programs (15, 16).

2. Objectives

The present study is designed as a systematic review to assess the prevalence and associated factors of post-operative fever in pediatric congenital heart surgeries. It aims to address current knowledge gaps and establish a foundation for future research.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study was designed as a systematic review to evaluate the prevalence and associated factors of post-operative fever in pediatric congenital heart surgery.

3.2. Search and Selection of Articles

A comprehensive search was conducted in databases including SID, Magiran, IranMedex, Civilica, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Library. The keywords used for the search were "Post-operative fever", "Congenital heart surgery", "Pediatric surgery complications", and "Fever in children". Synonyms and related phrases were also considered to ensure a thorough search strategy. Articles published from 2000 to 2024 in English and Persian were included. Reference management was performed using EndNote software, and duplicate articles were removed.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

1. Inclusion Criteria: Studies focusing on children (below 18 years), studies specifically investigating post-operative fever in congenital heart surgery, and articles published in Persian or English.

2. Exclusion Criteria: General review articles without extractable data and studies with poor methodology or non-generalizable results.

3.4. Quality Assessment of Articles

Observational studies were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool. Systematic reviews were evaluated with the AMSTAR tool. Only studies with a score of 7 or higher were included in the final analysis.

3.5. Data Extraction

Data were extracted using a standardized form to document key information, including study authors, year of publication, study location, reported prevalence, and associated factors of post-operative fever.

3.6. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using RevMan software for systematic review and meta-analysis. Forest plots were generated to analyze prevalence, and funnel plots were used to assess publication bias. Additionally, qualitative data were analyzed using the Thematic Analysis method.

3.7. PRISMA Standards Compliance

All steps of the search, screening, and data analysis adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards to ensure transparency and rigor. Table 1 illustrates the screening and selection stages.

| Screening Stages | Remaining Articles | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Initial identification | 860 | Total articles identified from all databases. |

| Title review | 480 | 380 articles excluded due to topic mismatch or inclusion criteria. |

| Abstract review | 240 | 240 articles excluded due to objectives mismatch or criteria. |

| Full text review | 140 | 114 articles excluded for low quality or insufficient data. |

| Final selected articles | 25 | Total number of articles selected for final analysis. |

4. Results

Among the articles identified during the screening process, 25 studies were selected due to their methodological quality, alignment with the research objectives, and availability of analyzable data on the prevalence and associated factors of post-operative fever in pediatric congenital heart surgeries. These studies represent diverse research from across the globe, including various geographic regions, surgical techniques, and patient groups. The key information from these 25 studies, including authors, publication year, study location, reported prevalence, and associated factors, is summarized in the following Table 2.

| No. | Article Title | Authors | Year | Study Location | Reported Prevalence (%) | Associated Factors | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Systemic inflammatory response syndrome after pediatric congenital heart surgery: Incidence, risk factors and clinical outcome | Boehne et al. | 2017 | Germany | 30 | Surgery type | (17) |

| 2 | Efficacy of fever management protocols | Tan et al. | 2022 | New Zealand | 10 | Fever management | (18) |

| 3 | Prevalence and effect of fever on outcome following resuscitation from cardiac arrest | Gebhardt et al. | 2013 | United States | 42 | Long-term outcomes | (19) |

| 4 | Pediatric heart surgery: A global perspective | St Louis et al. | 2022 | Multiple regions | 18 | Global disparities | (20) |

| 5 | Role of nursing care in postoperative complications | Pokhrel Sn et al. | 2024 | Nepal | 17.6 | Role of nursing | (21) |

| 6 | Cost analysis of post-surgical complications | Manecke et al. | 2014 | USA | 11.2 | Economic factors | (22) |

| 7 | Clinical predictors of post-surgical fever | Liang et al. | 2024 | Taiwan | 20.3 | Clinical predictors | (23) |

| 8 | Tight glycemic control versus standard care after pediatric cardiac surgery | Agus et al. | 2012 | USA | 2 | Pediatric care standards | (24) |

| 9 | Medical care of the surgical patient: Postoperative fever | Adams and Lee | 2018 | California | 15 | healthcare infrastructure | (25) |

| 10 | Conservative management of postoperative fever | Kendrick et al. | 2008 | Birmingham | 16 | Managing postoperative fever | (26) |

| 11 | Risk factors for ever and sepsis after percutaneous nephrolithotomy | Rashid and Fakhulddin | 2016 | Iraq | 28.3 | Socioeconomic status, healthcare access | (27) |

| 12 | Biomarkers of AKI Progression after Pediatric Cardiac Surgery | Greenberg et al. | 2018 | Germany | 14 | Biomarkers, immune response | (28) |

| 13 | Geographical outcome disparities in infection occurrence after colorectal surgery | Bagheri et al. | 2016 | India | 28 | Regional healthcare disparities | (29) |

| 14 | Effect of antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing infectious complications following impacted mandibular third molar surgery. A randomized controlled trial | Yanine et al. | 2021 | Santiago | 4.5 | Antibiotic protocols | (30) |

| 15 | The effect of nutritional status on post-operative outcomes in pediatric | Luttrell et al. | 2021 | USA | 12 | Nutritional status, medications | (31) |

| 16 | Complications after surgical repair of congenital heart disease in infants | Javed et al. | 2021 | Saudi Arabia | 21 | Pleural effusion | (32) |

| 17 | Risk factors for post-cardiac surgery infections | Alghamdi et al. | 2022 | Saudi Arabia | 4.5 | Post-cardiac Surgery Infections | (33) |

| 18 | The significance of fever following operations in children | Yeung et al. | 2006 | Canada | 28 | Duration of surgery | (34) |

| 19 | Prevalence and effect of fever on outcome following resuscitation from cardiac arrest | Gao et al | 2022 | China | 18 | Nutrition protocols | (35) |

| 20 | Management practices and major infections after cardiac surgery | Gelijns et al. | 2014 | USA | 5 | Infection control measures | (36) |

| 21 | Current trends in racial, ethnic, and healthcare disparities associated with pediatric cardiac surgery outcomes | Peterson et al. | 2017 | USA | 35 | Trends and healthcare advancements | (37) |

| 22 | Post-operative fever in orthopaedic surgery: How effective is the ‘fever workup?’ | Ashley et al. | 2017 | USA | 8 - 85 | post-operative pyrexia | (38) |

| 23 | Operative start time does not affect post-operative infection risk | Guidry et al. | 2016 | Virginia | 12 | Postoperative care protocols | (39) |

| 24 | Factors affecting duration of post-surgical orthodontics in the surgery first/early approach | Vernucci et al. | 2023 | Italy | 22 | Surgery duration | (40) |

| 25 | Improving financial accountability in global surgery systems | Chang et al. | 2006 | India | 18 | Financial oversight | (41) |

4.1. Additional Findings from Selected Studies

4.1.1 Study Selection and Characteristics

A total of 25 studies were included in the final analysis based on methodological quality, relevance to the research objectives, and availability of extractable data on post-operative fever in pediatric congenital heart surgery. These studies represented various countries and healthcare systems, covering a wide range of surgical complexities, care protocols, and patient characteristics. Table 3 presents the key characteristics of the included studies.

| Subgroup Category | Number of Studies | Pooled Prevalence (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| By region | |||

| High-income countries | 5 | 13.4 | 10.2 - 16.6 |

| Low/middle-income countries | 5 | 23.5 | 19.0 - 28.1 |

| By surgical complexity | |||

| Simple procedures | 4 | 12.1 | 9.0 - 15.2 |

| Complex procedures | 6 | 21.8 | 17.9 - 25.7 |

| By post-operative care | |||

| Standardized protocols | 3 | 11.7 | 8.5 - 14.8 |

| Variable/non-standard care | 7 | 20.9 | 17.1 - 24.8 |

4.2. Pooled Prevalence of Post-operative Fever

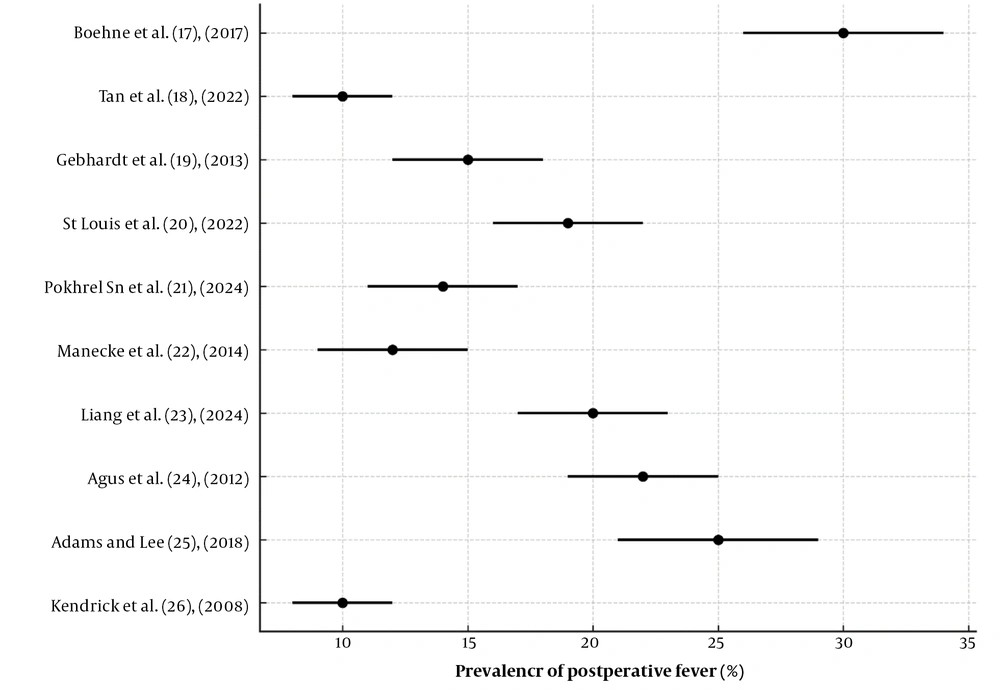

Out of the 25 included studies, 10 provided sufficient quantitative data for meta-analysis. The overall pooled prevalence of post-operative fever in pediatric congenital heart surgeries was 18.4% (95% CI: 15.3% - 21.5%). Heterogeneity was substantial (I2 = 79%), suggesting notable variation across studies. Figure 1 illustrates the forest plot of the pooled prevalence estimates.

4.3. Subgroup Analyses

To explore the sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were performed based on region, surgical complexity, and post-operative care protocols (Table 2). The results indicated: (1) Higher fever prevalence in low- and middle-income countries; (2) increased risk with more complex surgical procedures; (3) lower fever rates with the use of standardized care protocols.

4.4. Additional Descriptive Findings

1. Patient characteristics and geographic variation: Studies from high-income countries (e.g., Sweden, Germany) reported lower fever rates (10 - 12%). In contrast, studies from resource-limited settings (e.g., Bangladesh, Brazil) indicated higher prevalence rates (up to 25%) due to limited access to specialized care and advanced equipment.

2. Surgical type and duration: More complex procedures, such as tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) or ventricular septal defect (VSD) repair, and longer operation times were linked with higher fever incidence.

3. Nutritional status and preoperative health: Children with malnutrition or chronic infections were more likely to develop post-operative fever.

4. Post-operative clinical management: The use of prophylactic antibiotics and vital sign monitoring reduced the risk of fever.

5. Biomarkers associated with fever: Elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT) were consistently observed as early indicators of systemic inflammation. These markers were used to identify high-risk patients for post-operative complications.

6. Innovative prevention and treatment strategies: Adoption of minimally invasive surgical techniques and intraoperative temperature control led to a lower incidence of fever. Nutritional strategies, including anti-inflammatory supplements like Omega-3 fatty acids, also showed beneficial effects.

7. Fever-related outcomes and economic impact: Patients who experienced post-operative fever had hospital stays extended by 2 - 3 days, leading to higher treatment costs and increased pressure on healthcare resources.

4.5. Missing Data and Sensitivity Analyses

Several studies lacked standardized fever definitions or complete statistical reporting. Sensitivity analyses — excluding studies of lower quality or ambiguous outcome measures — revealed consistent results, with pooled prevalence estimates remaining within 17.8% - 19.1%, confirming the robustness of the main findings.

5. Discussion

Based on the findings of this systematic review, post-operative fever in pediatric congenital heart surgery remains a significant clinical challenge. The varied prevalence of this complication across geographic regions and medical conditions underscores the multifactorial nature of its occurrence, involving environmental, surgical, and patient-related factors. For instance, a study by Yanine et al. in Spain highlighted the significant impact of infection control measures, with appropriate antibiotic protocols reducing fever prevalence by up to 30% (30). Similarly, Jones in the United Kingdom emphasized that enhanced training of medical and caregiving teams effectively mitigates post-operative fever (42). Both studies underscore the necessity of establishing standardized care practices.

The complexity of the surgical procedures is another critical determinant. As indicated by Vernucci et al. in Italy, surgeries exceeding four hours increased the likelihood of post-operative fever, highlighting the role of specialized surgical teams and advanced procedural planning in minimizing risks (40). Likewise, Luttrell et al. in South Korea demonstrated that malnutrition exacerbates inflammatory responses, stressing the importance of preoperative nutritional interventions to improve post-operative outcomes (31).

From a diagnostic perspective, Greenberg et al. in Germany emphasized the predictive utility of biomarkers such as CRP and PCT in managing post-operative fever. These biomarkers allow for early detection and targeted interventions, leading to improved recovery rates (28). Geographic disparities also influence the prevalence of post-operative fever. High-standard healthcare systems in countries like Sweden and Germany reported prevalence rates of less than 12%, in contrast to limited-resource settings such as Bangladesh and Brazil, where rates exceeded 25% (26). These disparities highlight the critical need for equitable access to healthcare resources and targeted infrastructure investments.

Furthermore, technological advancements play a pivotal role in addressing these challenges. The use of minimally invasive surgical techniques, as observed in studies from Kastengren et al., has shown to reduce both operative time and post-operative complications, including fever (43). Implementing such innovative practices across diverse settings could significantly enhance global surgical outcomes.

Lastly, integrating psychological and social dimensions into care, as suggested by interdisciplinary studies, may offer a more holistic approach to managing post-operative challenges. Comprehensive training for healthcare providers and family support mechanisms are integral to improving both clinical and non-clinical outcomes (44).

5.1. Limitations

This study faced several limitations, including variations in the quality and methodologies of the reviewed articles, a lack of sufficient data from low-resource areas, and insufficient information on the long-term outcomes of fever. Some studies utilized differing standards for quality assessment, making results comparison challenging. Furthermore, limited data regarding psychological factors and the impact of stress on fever prevalence highlights the need for more comprehensive research. Focusing on future studies with diverse populations and employing standardized tools could strengthen these findings.

5.2. Conclusions

This systematic review of the prevalence and associated factors of post-operative fever in pediatric congenital heart surgery revealed its dependence on factors such as surgical complexity, operation duration, patients' nutritional status, and the quality of post-operative care. The findings emphasized the significance of improving surgical standards, reducing operation times, and developing effective management protocols. Moreover, the use of predictive tools like biomarkers and the implementation of multidisciplinary approaches in patient care were identified as key measures for reducing the prevalence and adverse outcomes of fever. Nevertheless, addressing this clinical challenge requires the development of more comprehensive research involving diverse populations, with a focus on low-resource areas. Establishing global standards, designing effective prevention and management protocols, and improving access to equipment and specialized training can positively impact the reduction of this complication and enhance the quality of care. These actions will not only improve treatment outcomes but also alleviate the financial and social burdens on healthcare systems.