1. Background

Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MIRI) is a significant clinical complication in vascular therapeutics. Although pharmacological therapies have been developed, the incomplete understanding of the pathophysiology of myocardial disease still limits the effectiveness of treating patients, necessitating mechanistic studies to close this gap (1). Ferroptosis is thought to be a major process in the progression of MIRI, as suggested by the growing literature (2-4). These results demonstrate the possible therapeutic benefit of targeting ferroptosis to reduce reperfusion-induced myocardial damage, and the investigation of new modulators of this pathway is urgently needed. Tetramethylpyrazine (TMP), a pharmacologically active molecule isolated from the traditional Chinese medicine Chuanxiong (Ligusticum chuanxiong), has been shown to be useful in the treatment of cardiovascular disorders. It has been reported (5, 6) that it works to reduce postreperfusion microvascular dysfunction and improve cardiac functional recovery in acute coronary syndrome patients. However, the mechanism underlying the cardioprotective effects of TMP, especially its putative relationship with ferroptosis regulatory networks in MIRI contexts, has not been well studied.

A solid foundation for the breakdown of various-target drug‒disease interactions is provided by the integration of network pharmacology with bioinformatic approaches. This method makes it possible to systematically predict therapeutic targets and mechanistic insights at the pathway level and, in turn, to effectively combine the use of empirical herbal medicine with the current systems biology paradigm. This research used computational pharmacology approaches that distinguish overlapping targets between TMP and MIRI pathogenesis, with a specific focus on molecular networks associated with ferroptosis.

2. Objectives

The goal of this study was to elucidate the multi-target mechanisms of TMP in MIRI mitigation, which will help with the clinical deployment of the evidence-based approach and provide new insights into ferroptosis modulation for ischemic cardiac diseases.

3. Methods

3.1. Tetramethylpyrazine Targets

The TMP-related targets were retrieved as follows.

3.1.1. Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database

Candidate targets of TMP were obtained via systematic searches of the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP; https://www.tcmsp-e.com/tcmsp.php). The main search term is chuanxiong. Molecular specificity was ensured by filtering results via the compound identifier "tetramethylpyrazine" within the platform's phytochemical screening module.

3.1.2. Structural Validation and Target Prediction

PubChem (https://pubchem.nih.gov/) provided the canonical SMILES notation and the three-dimensional structural configuration of the TMP for computational validation. Complementary target prediction was performed via three web-based platforms: PharmMapper (http://www.lilab-ecust.cn/pharmmapper/) for reverse pharmacophore mapping, SwissTarget Prediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/) for ligand-protein interaction profiling, and TargetNet (http://targetnet.scbdd.com/) for machine learning-driven target identification. Consensus targets across these platforms were prioritized for subsequent analysis. Targets were screened on the basis of the criteria of a probability > 0 in SwissTargetPrediction and probability > 0 in TargetNet. Duplicate entries were removed, and all TMP-related targets were standardized via the UniProt protein database (https://www.uniprot.org/).

3.2. Targets Related to Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury and Ferroptosis

3.2.1. Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury-Associated Targets

Using comprehensive queries from two genomic repositories, the possible therapeutic targets related to MIRI were methodically identified: GeneCards (http://www.genecards.org), a gene-disease association database, and DisGeNET (https://www.disgenet.org), a curated genomic variant repository. Standardized search protocols were implemented with "myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury" as the primary query term, with candidate targets filtered based on relevance scores exceeding platform-defined thresholds.

3.2.2. Ferroptosis-Related Genes

Genes related to ferroptosis, including driver genes, regulator genes, and marker genes, were extracted from the FerrDb database (http://www.zhounan.org/ferrdb/).

3.3. Shared Targets among Tetramethylpyrazine, Ferroptosis, and Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

Three different datasets were overlapped to find convergent therapeutic targets. Using Venn diagram visualization, a multidimensional analytical method was used to identify target intersections, which also revealed three binary intersections (TMP-MIRI, TMP-ferroptosis, and MIRI-ferroptosis dyads) and tripartite convergence nodes. These overlapping targets, representing shared molecular mechanisms among the three biological domains, were prioritized for subsequent mechanistic investigations.

3.4. Construction of a Protein-Protein Interaction Network and Identification of Hub Targets

The shared molecular targets between TMP and MIRI pathogenesis were subjected to protein-protein interaction (PPI) network modeling via the STRING database (https://string-db.org/), employing an interaction confidence threshold (> 0.4) to filter spurious associations. Network topology was subsequently analyzed via Cytoscape 3.10.3, with vertices representing molecular entities and edges indicating functional associations. Hub targets were computationally ranked with the CytoNCA plugin by utilizing various multiparametric centrality indices, including Degree (DC), Eigenvector (EC), Information (IC), Betweenness (BC), Closeness (CC), and Network (NC) indices. Nodes that exceeded the median distribution values for these metrics were identified as topologically critical.

3.5. Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome Enrichment Analysis

Enrichment analyses for the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome (KEGG) analyses of the intersecting targets were performed via the "clusterProfiler" package in R software. The significantly enriched results were visualized via the "ggplot2" package.

3.6. Molecular Docking

3.6.1. Target Preparation

Core targets identified in section 1.4 and shared targets between TMP and ferroptosis were submitted to the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (https://www.rcsb.org/) to obtain corresponding protein structures, which were downloaded in PDB format as receptor files. PyMOL software (https://pymol.org/) was used to remove water molecules from the receptor structures.

3.6.2. Ligand Preparation

The three-dimensional chemical structure of TMP was initially obtained from PubChem (https://pubchem.nih.gov/) as an SDF-formatted file. Structural refinement was performed via ChemOffice 22.0 to generate a stable molecular configuration, which was subsequently exported in the PDB file format for computational validation.

3.6.3. Docking Procedure

Molecular preprocessing was performed via AutoDock Tools 1.1.2, which involves the removal of solvent molecules and the systematic addition of polar hydrogens to receptors. Binding site localization was determined by defining the grid parameter boxes with which the anticipated ligand-binding pockets were contained in the binding site. Docking simulations were executed via AutoDock Vina 1.2.3, with binding free energy values calculated to quantify intermolecular interactions.

3.7. in vitro Experiments

3.7.1. Cell Line

The H9C2 rat cardiomyoblast cell line was obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The culture medium was replaced every 2 days. When cell density reached 80 - 90%, cells were digested using 0.05% trypsin. H9C2 cells were seeded into 6-well plates or 96-well plates and treated according to subsequent experimental protocols.

3.7.2. Drugs and Reagents

Ligustrazine hydrochloride injection (TMP) was produced by Changzhou Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (specification: 40 mg/vial). Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) was purchased from Medchem Express (Shanghai, China). Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels were detected using the fluorescent probe 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Sigma, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescent images of intracellular ROS were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX51, Japan). The mean fluorescence intensity was analyzed using an image analysis system (Image J, National Institutes of Health, USA). GPX4 expression was detected by Western blotting. Total protein was extracted from treated H9C2 cells in each group using a protein extraction kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and its concentration was quantified using a BCA assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Fifty micrograms (50 µg) of protein were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Immunoblotting was performed using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (ECL; Biosharp, BL520A) combined with a Western blot system (Auragene). The integrated optical density of the target bands relative to the loading control was quantified using the image analysis system (Image J, National Institutes of Health, USA).

3.7.3. Experimental Groups

1. Blank control group: No treatment.

2. Ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) model group: Cells were placed in a constant-temperature tri-gas incubator (37°C, 95% N2, 5% CO2, 1% O2) for 4 hours to establish a hypoxia model. Subsequently, the culture dishes were transferred to a normoxic incubator and cultured for 2 hours to establish the reoxygenation model.

3. The TMP treatment group: After establishing the hypoxia model, 20 μM TMP was added, followed by reoxygenation.

4. The Fer-1 treatment group: After establishing the hypoxia model, 20 μM Fer-1 was added, followed by reoxygenation.

A completely randomized grouping principle was adopted, with cultured H9C2 cells being randomly assigned to the various experimental groups. Each group had 10 replicate samples at the 2-hour reoxygenation time point for the detection of ROS and GPX4 levels. The mean fluorescence intensity of ROS in the blank control group was set as 100, and the mean expression level of GPX4 was set as 1.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

3.8.1. Software Used For Each Task

3.8.1.1. Online Tools

Target normalization was performed using the UniProt protein database (https://www.uniprot.org/). Venn diagrams were generated using Oliveros, JC (2007 - 2015) Venny (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html). The PPI network construction was conducted using the STRING database (https://string-db.org/).

3.8.1.2. Local Software

Network visualization and topological analysis were performed using Cytoscape (v3.10.3). Hub target identification was carried out using the CytoNCA plugin for Cytoscape. The GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were implemented using the clusterProfiler and ggplot2 packages in R software. Macromolecular structure preprocessing was done using PyMOL. Ligand structure optimization and format conversion were handled with ChemOffice (v22.0). Docking simulations and binding energy calculations were executed using AutoDock Tools (v1.1.2) and AutoDock Vina (v1.2.3). Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 26.0). Statistical power analysis was performed using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7). Graphical abstracts and schematic diagrams of core target interactions were created with Photoshop CS5.

3.8.2. Statistical Analysis for Group Comparisons

Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ± s). Comparisons between two groups were conducted using the Student's t-test. A P-value of less than 0.05 (P < 0.05) was considered statistically significant. Prior to intergroup comparisons, all continuous data were assessed for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test, which confirmed that the data were normally distributed (P > 0.05). Intergroup differences were evaluated using Student's t-test. Furthermore, upon completion of data analysis, we conducted a post-hoc statistical power analysis to evaluate the reliability of the test results under the current sample size and observed effect size.

4. Results

4.1. Tetramethylpyrazine Targets

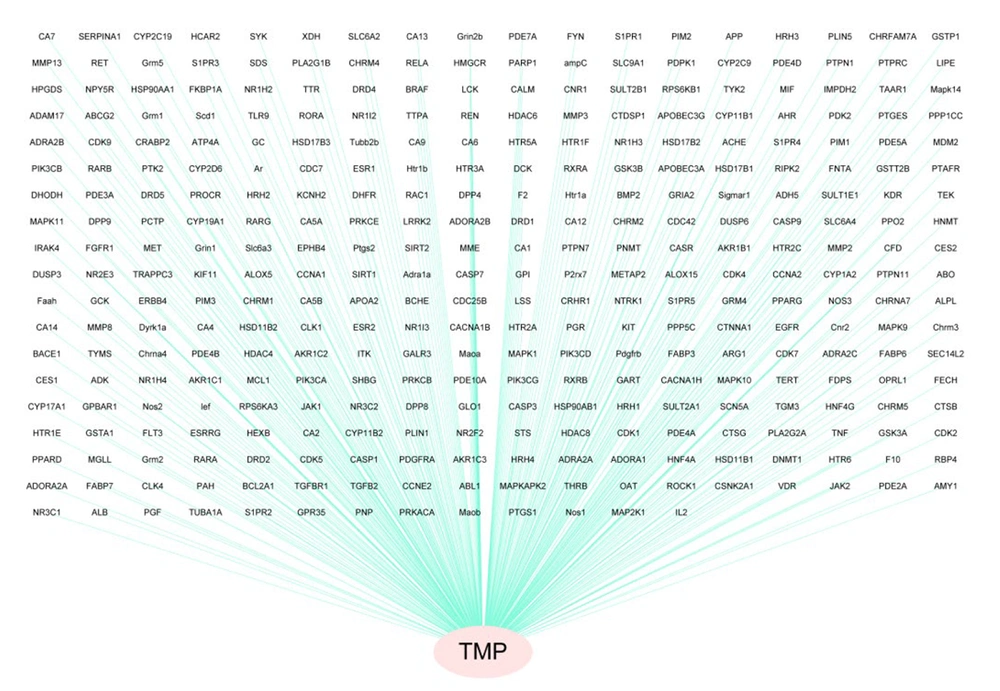

Four hundred nineteen TMP targets were identified via detailed multiple platform interrogation. A bipartite network graph was constructed via Cytoscape 3.10.3 to map compound-target relationships, with TMP depicted as red vertices and its corresponding targets illustrated as blue vertices via topological visualization (Figure 1). This computational framework systematically delineates the polypharmacological characteristics of TMP through node interactions.

4.2. Shared Targets among Tetramethylpyrazine, Ferroptosis, and Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

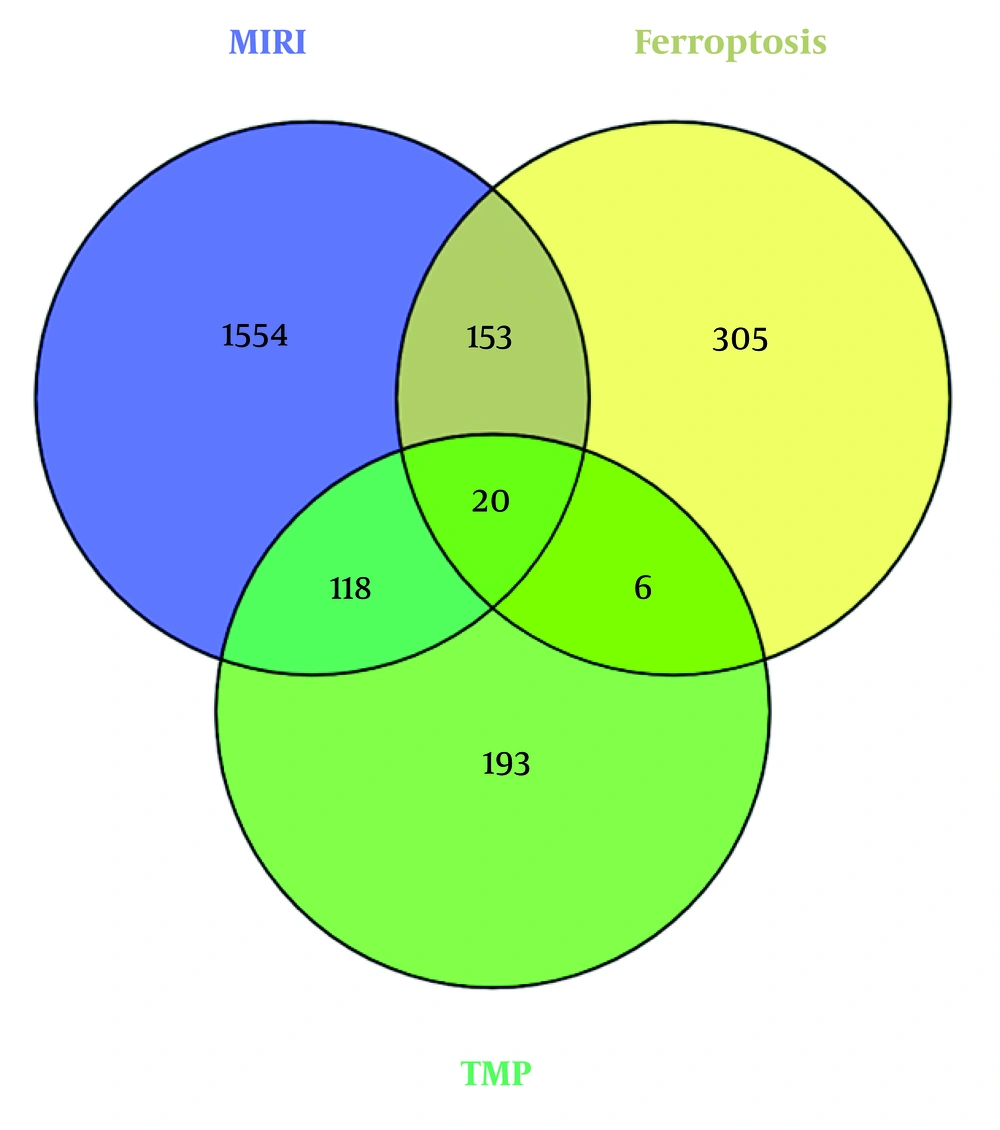

The FerrDb repository yielded 484 curated gene entries relevant to ferroptosis regulation. Concurrently, systematic interrogation of GeneCards and DisGeNET identified 1,845 nonredundant molecular targets linked to MIRI pathogenesis following data harmonization and redundancy removal procedures. A total of 138 shared genes were obtained for overlapping TMP targets with MIRI-related targets. Among these genes, 20 were further identified as overlapping with ferroptosis-related genes, as illustrated in a Venn diagram (Figure 2).

4.3. Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome Enrichment Analyses

4.3.1. Gene Ontology Enrichment Analysis

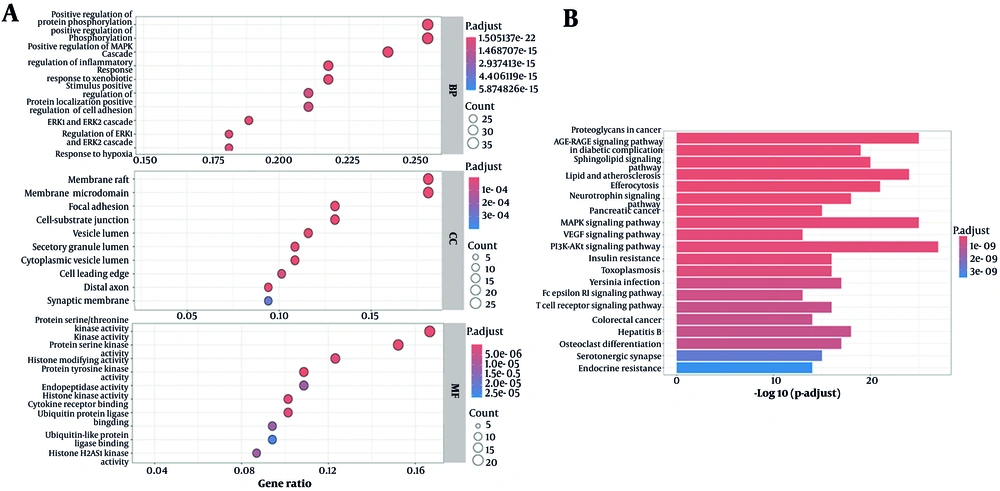

Functional enrichment analysis revealed predominant involvement in signal transduction modulation, particularly protein phosphorylation dynamics and MAPK signaling cascade activation. Additional mechanistic associations included inflammatory pathway regulation and cellular responses to xenobiotic compounds. In the lipid rafts and specific membrane microdomains, spatial mapping revealed notable enrichment. Protein serine/threonine kinase activity, protein serine kinase activity, and histone-modifying activity are important functions that are associated with molecular functions (Figure 3A).

A, graph of the gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis results; the larger the circle in the figure, the greater the number of relevant targets; B, graph of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome (KEGG) enrichment analysis results; the longer the column in the figure, the more related targets – a redder color represents a higher degree of enrichment.

4.3.2. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome Enrichment Analysis

Pathway enrichment analysis revealed statistically significant associations with oncogenic proteoglycan (PG) signaling, dysregulated lipid metabolism in atherogenesis, and efferocytotic clearance mechanisms. Additional mechanistic information is detailed in the pathway topology map (Figure 3B).

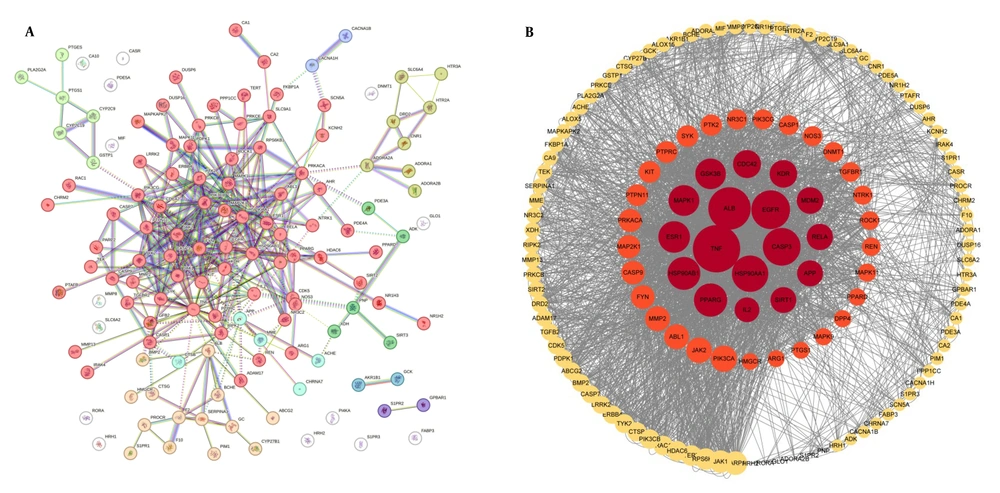

4.4. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Construction and Core Target Screening

A total of 138 shared targets were identified by intersecting TMP-related targets and MIRI-associated targets. These targets were then combined with the STRING database to construct a PPI network (Figure 4A). Seventeen key molecular targets were identified according to the centrality indices of CytoNCA, and the top 10 targets were as follows: TNF, ALB, EGFR, CASP3, HSP90AA1, PPARG, ESR1, HSP90AB1, GSK3B, and MAPK1. In the graph representation (Figure 4B), nodes were scaled based on the degree of centrality of each node, which was then visually highlighted with the possibility of potential network influence.

A, protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of targets between Tetramethylpyrazine (TMP) and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MIRI); B, hub targets ranked with CytoNCA; the red and orange nodes represent targets that exceeded the median of all indicators during the initial screening. Among these nodes, the red nodes denote that the core targets surpassed the median values during the secondary screening; the larger the node in the figure, the greater the degree centrality of the representative target.

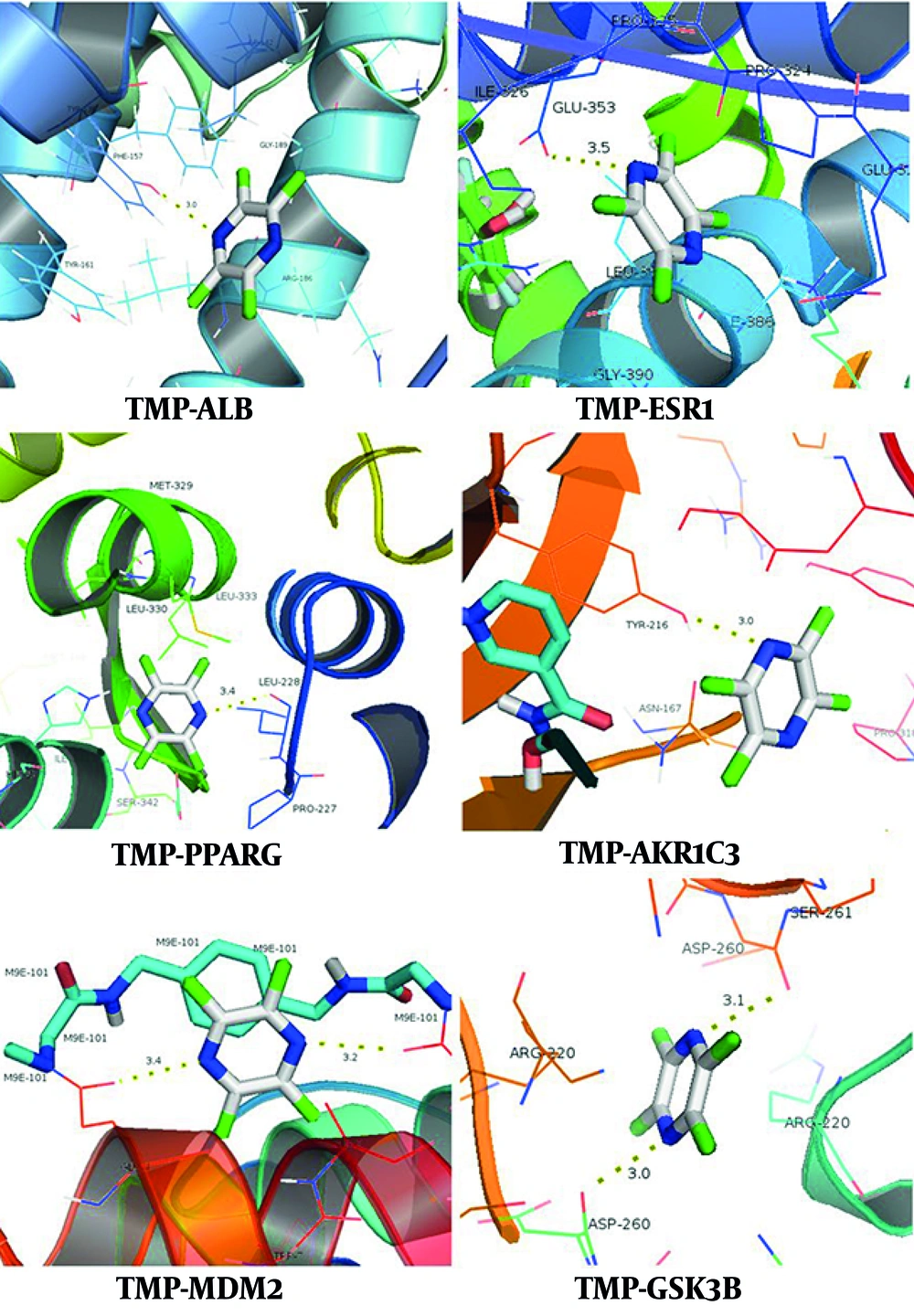

4.5. Molecular Docking

Computational validation via molecular docking simulations was conducted between TMP and two target groups: Seventeen topologically prioritized proteins identified through CytoNCA-based network analysis and 6 ferroptosis-associated genes that intersected with the therapeutic targets of TMP. Thermodynamic profiling revealed favorable intermolecular interactions (ΔG < -5 kJ/mol) between TMP and multiple critical targets, including seven ferroptosis regulators. The comprehensive thermodynamic parameters are tabulated in Table 1, with three-dimensional binding conformations illustrated in Figure 5. The observed binding affinities indicate that TMP has the ability to modulate dual pathways via both ferroptosis-dependent and ferroptosis-independent mechanisms.

| Projects and Gene Names | Binding Free Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| Non-ferroptosis related targets | |

| ALB | -6.4 |

| ESR1 | -6.0 |

| CDC42 | -5.8 |

| TNF | -5.6 |

| IL-2 | -5.5 |

| APP | -5.4 |

| CASP3 | -5.3 |

| KDR | -5.1 |

| Ferroptosis-related targets | |

| PPARG | -5.3 |

| MDM2 | -5.1 |

| SIRT1 | -5.0 |

| GSK3B | -5.0 |

| AKR1C3 | -6.0 |

| AKR1C2 | -5.4 |

| DHODH | -5.3 |

| TTPA | -5.2 |

4.6. Anti-ferroptosis Effects of Tetramethylpyrazine

Compared with the control group, the model group exhibited a significant increase in ROS levels and a decrease in GPX4 expression. Compared with the model group, both the TMP group and the Fer-1 group showed significantly reduced ROS levels and increased GPX4 expression (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 2.

| Groups | ROS (Relative Fluorescent Intensity) | GPX4 (Relative Expression Quantity) |

|---|---|---|

| Control group | 100 | 100 |

| I/R model group | 185.66 | 0.3936 |

| TMP group | 172.88 | 0.5538 |

| Fer-1 group | 144.1 | 0.849 |

Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen species; I/R, ischemia-reperfusion; TMP, tetramethylpyrazine; Fer-1, ferrostatin-1.

The statistical power assessment demonstrated that under the study design with a sample size of n = 10 per group and the observed effect size, the statistical power for the primary outcome measures exceeded 90%, indicating that the study had sufficient capability to detect existing significant differences.

5. Discussion

Recent reports have shown that during MIRI progression, ferroptosis is a critical pathomechanism (7, 8) caused by a metabolically programmed cell death mechanism. The pathophysiological environment of reperfusion is characterized by excessive production of ROS and disruptions in iron homeostasis, which together foster conditions conducive to ferroptotic processes. This, in turn, leads to devastating oxidative alterations in cellular macromolecules, including membrane lipids, structural proteins, and genetic material. These pathobiological findings highlight ferroptosis inhibition as a strategic therapeutic axis in MIRI management. Nevertheless, mechanistic crosstalk between ferroptotic pathways and current pharmacological modalities remains insufficiently characterized, limiting the development of synergistic therapeutic regimens.

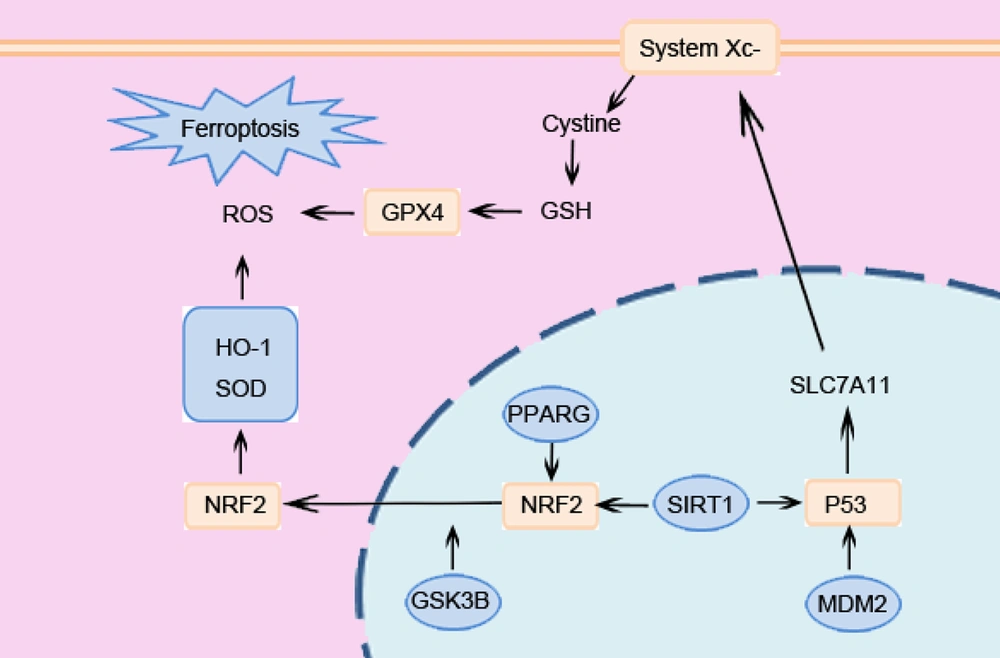

TMP, a bioactive alkaloid from Chuanxiong (Ligusticum chuanxiong), has been shown to have cardioprotective properties in preclinical MIRI models that are related to its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antiapoptotic qualities (9). Nevertheless, there has not been a systematic investigation into its possible function in controlling MIRI through the ferroptosis pathway. This knowledge gap hinders the optimization of TMP-based therapies and the identification of novel targets for combination approaches. Through the construction and analysis of a drug-target PPI network, this study identified 17 core targets, 7 of which are associated with ferroptosis, highlighting ferroptosis as a critical mechanism underlying the therapeutic effects of TMP against MIRI. The strong binding affinities between TMP and these main targets were further confirmed by molecular docking. Notably, the ferroptosis-related targets PPARG, MDM2, SIRT1, and GSK3B also demonstrated robust binding affinities with TMP, further confirming their critical role in mediating the dual regulatory effects of TMP on ferroptosis inhibition and MIRI alleviation.

SIRT1, an NAD+-dependent deacetylase, confers cytoprotection in I/R contexts through the regulation of autophagy, redox homeostasis, and programmed cell death pathways (10, 11). Within the ferroptosis pathway network, SIRT1 functions as a master redox sensor against ferroptosis by coordinating the activities of key transcription factors Nrf2 and p53 (12, 13). SIRT1 promotes Nrf2-mediated transcription of critical antioxidant enzymes (e.g., HO-1, NQO1) essential for combating lipid peroxidation (14). Concurrently, SIRT1-mediated regulation of p53 adds another layer of control over ferroptosis susceptibility, where MDM2 emerges as a key interaction partner. Studies demonstrate that MDM2 promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of p53, thereby alleviating p53-mediated suppression of the ferroptosis inhibitors SLC7A11 and GPX4 (15, 16).

PPARγ, functioning as a ligand-activated transcriptional regulator, influences transcriptional activity at diverse genomic loci. Previous studies indicate that the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone attenuates I/R injury in mice, potentially involving the PPARG-Nrf2 axis to bolster defense against ferroptotic damage (17). However, the nuclear activity of Nrf2 and its protective output are dynamically regulated by GSK3β. Active GSK3β promotes Nrf2 nuclear export, terminating its transcriptional program (18). Consequently, inhibiting GSK3β activity is crucial for sustained Nrf2-mediated antioxidant gene expression and ferroptosis suppression.

The interplay among these four targets (SIRT1, PPARG, GSK3β, and MDM2) forms an amplified protective cascade, as shown in Figure 6. Owing to the congruence of the target and pathway, TMP has therapeutic potential as a multitarget pharmacological tactic to affect the myocardial damage mediated by ferroptosis, which is characterized by the regulation of inflammatory signaling and oxidative stress.

The GO enrichment profiling revealed kinase-mediated signaling regulation as the main biological mechanism underlying the cardioprotective efficacy of TMP against MIRI, with statistically significant associations with phosphoregulation, including MAPK cascade activation and protein kinase activity potentiation. The MIRI pathobiology involves a complicated translational modification network, especially reversible protein phosphorylation relationships that regulate cellular stress adaptation. Experimental evidence suggests that phosphorylation-mediated Nrf2 activation through GSK-3β inactivation promotes redox homeostasis in myocardial tissue (19) and that AMPK dephosphorylation-induced metabolic inflexibility exacerbates ischemic organ damage through impaired mitophagy (20). In addition, a variety of molecules may be involved in the regulation of I/R injury via phosphorylation (21-25). This phosphoproteomic plasticity establishes protein kinase networks as critical therapeutic targets for modulating MIRI progression.

Studies have demonstrated that MAPK pathway activation triggers proinflammatory cytokine release and amplifies ROS generation, thereby intensifying oxidative stress (26). Additionally, MAPK signaling is closely linked to apoptosis, serving as a key driver of programmed cell death (27,28). The cumulative experimental evidence established that the cardioprotective efficacy of TMP against MIRI is mediated through ferroptosis regulatory networks, particularly redox homeostasis restoration.

The KEGG pathway enrichment profiling revealed the pharmacological efficacy of TMP against MIRI through three principal mechanistic axes: The PGs in cancer, lipids and atherosclerosis, and efferocytosis pathways.

The PGs play significant roles in both cancer and MIRI, yet exhibit marked differences in their mechanisms of action and biological effects. The PGs in cancer (e.g., Versican) induce metabolic reprogramming, promote the Warburg effect to support cancer cell proliferation, and simultaneously enhance antioxidant defenses (e.g., by upregulating SOD) (29). During early reperfusion, cardiomyocytes in the ischemic zone shift to glycolysis due to ATP depletion, mimicking the Warburg effect. However, lacking the antioxidant reserves of cancer cells, this leads to increased susceptibility to ferroptosis. Concurrently, endothelial cell Versican expression is upregulated. While this enhances SOD-mediated defense, it also promotes local lipid retention by binding LDL (30). Atherogenic lipid accumulation exacerbates endothelial dysfunction through oxidized LDL-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome priming, creating a proinflammatory milieu that exacerbates reperfusion-induced oxidative damage (31).

Efferocytosis plays a pivotal role in mitigating inflammation and promoting tissue repair through the phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells by macrophages (31, 32). However, lipid overload can impair efferocytosis, leading to foam cell formation and an inability to efficiently clear apoptotic cardiomyocytes, resulting in increased secondary necrosis (33). Efferocytosis impairment can further release oxidized phospholipids and free iron, facilitating trans-cellular damage propagation (34). In summary, PGs, atherosclerotic lipid accumulation, and efferocytosis form a synergistic network through metabolic reprogramming, inflammation amplification, and cell death pathways, playing a pivotal role in MIRI. This network is closely intertwined with ferroptosis pathways.

Cell-based experiments revealed that ferroptosis is involved in the damage of cardiomyocytes during the hypoxia/reoxygenation process. Both the ferroptosis inhibitor and TMP could alleviate cardiomyocyte ferroptosis, suggesting the unique role of TMP in mitigating MIRI.

Current therapeutic agents for MIRI and their mechanisms are as follows.

1. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents.

2. Cell death modulators, including agents targeting anti-apoptosis, anti-pyroptosis, and autophagy regulation.

3. Organelle function protectants such as calcium overload inhibitors, mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening inhibitors, and endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) inhibitors.

4. Long-term adaptive therapeutic agents like statins (providing pleiotropic protection for endothelium and mitochondria), which sustain long-term efficacy through lipid-lowering, anti-inflammatory actions, and microcirculatory improvement (35).

The TMP offers complementary mechanisms — inhibiting ferroptosis, reducing lipid accumulation, and enhancing efferocytosis — synergizing with existing drugs at distinct targets. Furthermore, TMP exhibits novelty in the following aspects. While existing drugs primarily focus on inflammation, oxidation, and calcium homeostasis, TMP's anti-ferroptosis and anti-lipid accumulation effects seem to directly reduce damage to cardiomyocytes. On the other hand, TMP actively promotes inflammation resolution and tissue repair by "enhancing efferocytosis" to clear damaged cells and debris. This "pro-repair" mechanism complements the "damage-suppression" mechanisms of existing agents.

The shortcomings of this study include:

1. The TMP targets mainly depend on TCMSP. Although we also predict targets from Pharmmapper, SwissTargetPrediction, and Targetnet databases based on the structure of TMP, there is still a possibility that the relevant targets are not comprehensive.

2. The targets obtained from the FerrDb database may have inherent limitations in terms of update latency and potential lack of the latest information. Thus, we complement the functional annotation by employing additional methods such as GO and KEGG analyses.

5.1. Conclusions

Collectively, the network pharmacology and molecular docking studies indicate that TMP has cardioprotective effects on ischemia‒reperfusion pathology, which is likely mediated by ferroptosis regulatory networks, including the PPARG, MDM2, SIRT1, and GSK3B signaling hubs. These computational insights demonstrate the polypharmacological ability of TMP in decreasing oxidative and inflammatory cascades. Comprehensive functional validation is necessary to mechanistically establish the function of TMP as a multitarget ferroptosis inhibitor and define its therapeutic hierarchy in MIRI pathobiology.