1. Background

Coronary artery ectasia (CAE) is an uncommon cardiovascular anomaly observed in a small percentage (ranging from 1% to 5%) of patients undergoing coronary angiography for the evaluation of coronary artery disease (CAD) (1). The CAE is defined as the dilation of a coronary artery segment with a diameter more than 1.5 times that of the adjacent normal segments (2). The extent of arterial dilation in CAE can vary. The term "coronary artery aneurysm" typically refers to a short and focal segment of dilation, whereas "ectasia" denotes more diffuse lesions involving more than one-third of the vessel length (3, 4). The clinical presentation of CAE closely resembles that of CAD, including stable angina and acute coronary syndrome, which may result from coronary thrombus formation or vasospasm (5, 6). The primary cause of angina in CAE is turbulent and slow blood flow through the aneurysmal dilation of the coronary artery (7).

Regarding etiology, CAE has been associated with several potential factors, including rheumatologic disorders, systemic inflammatory diseases, congenital origins, and iatrogenic causes. However, atherosclerosis is particularly notable, accounting for more than 50% of cases (1). Despite these associations, the precise mechanism underlying ectasia formation remains unknown. The frequent co-existence of CAE and CAD has led to speculation that CAE may represent a variant of CAD (8). Notably, from a histopathological perspective, there are distinct differences: In CAE, destruction of the musculoelastic layer in the ectatic arterial wall is not typically linked to local atherosclerosis of the artery (9).

Recent studies have suggested that inflammation may play a role in the development of CAE. Mediators of chronic inflammation, including cytokines, proteolytic substances, growth factors, cellular adhesion molecules, and systemic inflammatory mediators, have been implicated in its pathogenesis (10, 11). Several inflammatory pathways are known to contribute to atherosclerosis, where these mediators promote plaque formation, progression, and rupture (12). Thus, understanding how atherosclerosis-related inflammation differs from that in CAE, and whether it fully accounts for CAE's development, remains a significant challenge (8). Despite advances in knowledge, the exact pathophysiology of CAE is still unclear, and there is no consensus regarding its underlying mechanisms.

2. Objectives

To address this gap, the present study aims to compare inflammatory biomarker levels in patients with CAE, stenotic CAD, and normal coronary arteries. The study will investigate whether specific inflammatory biomarkers can differentiate CAE from stenosis and identify potential biomarkers that may serve as prognostic indicators and inform clinical management.

3. Methods

This prospective observational study was designed to compare inflammatory biomarker levels in patients diagnosed with CAE and aneurysmal dilation versus patients with CAD. The study population comprised 48 patients who underwent coronary angiography at Alzahra Hospital between July 2024 and December 2024. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The study protocol adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (approval ID: IR.SUMS.MED.REC.1403.294).

Patients underwent elective angiography for stable angina pectoris, as confirmed by clinical history, normal electrocardiographic findings, and negative cardiac biomarkers (e.g., troponin). Angiographic evaluations were performed by two independent cardiologists who were blinded to the patients’ clinical and laboratory data, thereby minimizing observer bias. Patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome or unstable angina, previous myocardial infarction, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, severe valvular heart disease, immunologic or inflammatory diseases, hematological disorders, active local or systemic infections, or a history of malignancy were excluded. Additionally, patients who had taken any systemic anti-inflammatory agents (including corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or immunosuppressants) within the preceding four weeks were excluded.

Participants were categorized into three distinct groups based on angiographic findings: (1) The CAE/aneurysmal dilation group (10 patients), (2) stenotic CAD group (19 patients), and (3) a control group (19 patients). The control group comprised individuals with completely normal coronary arteries, without any detectable luminal irregularity or stenosis (< 10%), and no history of cardiovascular disease. The CAE was defined as a segmental coronary artery diameter exceeding 1.5 times that of the adjacent healthy reference segment, in line with prior studies.

Baseline demographic characteristics (age and sex) and cardiovascular risk factors were extracted from medical records. The use of statins and low-dose aspirin was also documented. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that there were no significant differences in biomarker levels after adjusting for these factors.

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected immediately after coronary angiography to measure inflammatory biomarkers, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), using standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Karmania Pars Gene company). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to blood sampling.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 25.0. Qualitative variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables were summarized as means and standard deviations. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparisons of inflammatory biomarker levels among the three groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for normally distributed variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for variables not following a normal distribution. Post-hoc analyses were conducted using Bonferroni or Tukey tests to identify significant differences between specific groups. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Given the limited sample size and exploratory nature of the study, no formal power calculation was conducted prior to enrollment. However, a post-hoc power analysis based on the observed effect size for IL-1β (η2 = 0.28) indicated a statistical power of approximately 72% at a significance level of 0.05.

4. Results

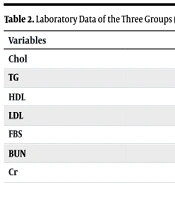

The baseline demographic characteristics, including sex and age, as well as laboratory data such as lipid profile, fasting blood sugar (FBS), and kidney function tests, are presented in Tables 1 and 2. There were no statistically significant differences in these parameters among the three groups.

| Variables | Normal | CAE | CAD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 54.94 ± 13.81 | 54.85 ± 14.28 | 62.82 ± 12.79 | 0.069 |

| Sex (male) | 73.7% (14) | 87.5% (7) | 94.7% (18) | 0.751 |

Abbreviations: CAE, coronary artery ectasia; CAD, coronary artery disease.

a Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or No. (%).

| Variables | Normal | CAE | CAD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chol | 141.50 ± 42.22 | 112 ± 46.7 | 131.71 ± 35.7 | 0.601 |

| TG | 131.33 ± 35.70 | 110.33 ± 34.8 | 111.00 ± 33.42 | 0.206 |

| HDL | 36.63 ± 4.66 | 39.2 ± 12.8 | 40.29 ± 11.48 | 0.491 |

| LDL | 75.50 ± 28.55 | 60.1 ± 23.5 | 67.96 ± 24.91 | 0.558 |

| FBS | 105.17 ± 22.57 | 110.13 ± 35.8 | 109.32 ± 44.70 | 0.766 |

| BUN | 16.50 ± 3.89 | 16.14 ± 5.4 | 17.19 ± 7.08 | 0.742 |

| Cr | 0.97 ± 0.27 | 0.995 ± 0.18 | 0.98 ± 0.14 | 0.827 |

Abbreviations: CAE, coronary artery ectasia; CAD, coronary artery disease; FBS, fasting blood sugar.

a Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

4.1. Immune Inflammatory Response

The distribution of IL-1β variables was normal, so one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey tests was used for intergroup comparisons. Other biomarkers, including hsCRP, IL-6, and TNF-α, were not normally distributed and were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The results of inflammatory biomarker comparisons among the three groups are summarized in Table 3.

| Variables | Normal | CAE | CAD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.94 ± 1.56 | 1.29 ± 1.36 | 1.71 ± 1.73 | 0.367 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 73.15 ± 8.07 | 75.17 ± 9.17 | 75.61 ± 9.51 | 0.687 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 12.01 ± 7.27 | 12.80 ± 7.06 | 10.19 ± 3.31 | 0.468 |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 18.85 ± 7.90 | 17.53 ± 6.20 | 35.08 ± 13.30 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: CAE, coronary artery ectasia; CAD, coronary artery disease; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-1β, interleukin-1 beta.

a Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

b P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4.2. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha

The TNF-α levels did not significantly differ among the three groups (P = 0.891). The mean TNF-α concentrations were 75.61 ± 9.51 pg/mL in the stenotic CAD group, 75.17 ± 9.17 pg/mL in the CAE group, and 73.15 ± 8.07 pg/mL in the control group.

4.3. Interleukin-6

The IL-6 levels were also not significantly different among the groups (P = 0.440), with mean values of 10.19 ± 3.31 pg/mL in the stenotic CAD group, 12.80 ± 7.06 pg/mL in the CAE group, and 12.01 ± 7.27 pg/mL in the control group.

4.4. Interleukin-1 Beta

In contrast, IL-1β levels showed a highly significant difference (P < 0.001). The stenotic CAD group had a substantially elevated mean IL-1β level (35.08 ± 13.30 pg/mL) compared to the CAE group (17.53 ± 6.20 pg/mL) and the control group (18.85 ± 7.90 pg/mL). Post-hoc analysis confirmed that the stenotic CAD group differed significantly from both the CAE group (P < 0.001) and the control group (P < 0.001), while no significant difference was found between the CAE and control groups (P = 0.846).

4.5. High-sensitivity C-reactive Protein

Comparison of hsCRP levels among the three groups revealed no statistically significant difference (P = 0.367). Mean hsCRP levels were 0.94 ± 1.56 mg/L in the control group, 1.29 ± 1.36 mg/L in the CAE group, and 1.71 ± 1.73 mg/L in the stenotic CAD group.

5. Discussion

This prospective observational study evaluated inflammatory biomarkers, including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and hsCRP, in patients with CAE, CAD, and normal coronary arteries. The findings revealed no significant differences in TNF-α (P = 0.891), IL-6 (P = 0.440), or hsCRP (P = 0.367) among the groups. In contrast, IL-1β levels were significantly elevated in the CAD group (35.08 ± 13.30 pg/mL) compared to both the CAE group (17.53 ± 6.20 pg/mL) and controls (19.78 ± 8.67 pg/mL, P < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in IL-1β levels between the CAE group and controls (P = 0.846).

The elevated IL-1β levels observed in the stenotic CAD group compared to the control group are consistent with the established role of IL-1β in atherosclerosis. The IL-1β is a pivotal pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in multiple stages of atherosclerosis; it acts on endothelial cells by increasing the expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines, which promote the recruitment of monocytes and their differentiation into macrophages. These macrophages subsequently become foam cells, a hallmark of early atherosclerotic lesions (13). The IL-1β also stimulates the production of matrix metalloproteinases, leading to extracellular matrix degradation and eventual plaque rupture through weakening of the fibrous cap (14). Furthermore, elevated IL-1β levels have been associated with a greater risk of adverse cardiovascular events (13). The CANTOS trial demonstrated that canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, significantly reduced the incidence of recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with a history of myocardial infarction, independent of any changes in baseline lipid levels (15). These findings suggest that targeting IL-1β may be an effective therapeutic strategy for reducing inflammation and improving cardiovascular outcomes.

Moreover, our study revealed significantly higher IL-1β levels in the stenotic CAD group compared to the CAE group, a finding that contrasts with the results reported by Boles et al. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is the greater CAD severity in our cohort, which was characterized by substantial luminal stenosis (> 70%). In contrast, the study by Boles et al. (16) included patients with predominantly mild, non-obstructive disease (< 20% stenosis).

The absence of significant differences in TNF-α, IL-6, and hsCRP levels among groups differs from the results of several prior studies that found elevated levels of these biomarkers in CAE. For example, a meta-analysis by Vrachatis et al. (17) found that TNF-α, IL-6, and hsCRP were significantly higher in CAE patients compared to controls, and that hsCRP was higher in CAE patients than in those with CAD, suggesting a role for inflammation in CAE pathophysiology. Similarly, Brunetti et al. (18) and Boles et al. (16) reported increased TNF-α and IL-1β levels in CAE patients compared to CAD patients and healthy controls.

Several factors may account for these discrepancies. First, differences in patient demographics are notable; our CAE cohort was relatively small (n = 10), younger, and had fewer comorbidities. In contrast, the study by Boles et al. enrolled older patients (mean age 64.5 years), nearly half of whom had cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension. Second, the assay methods used for biomarker detection may influence results. For example, Boles et al. used a highly sensitive multiplex ELISA kit, whereas we used standardized ELISA kits, which may have limited sensitivity for detecting low-grade systemic inflammation.

Additionally, a key distinction of our study is that we did not stratify CAE patients by the extent or morphology of ectasia. Previous studies suggest that the inflammatory profile of CAE may vary according to the degree and progression of ectasia. Brunetti et al. found a marked increase in IL-1β and IL-10 levels with decreasing Markis class (18). Another study reported that hsCRP levels were higher in diffuse and multivessel ectasia subgroups compared to focal and single-vessel ectasia subgroups (19). The absence of significant differences between the CAE group and other groups in our study may be attributed to a lower prevalence of diffuse or multivessel involvement, which is more likely to result in endothelial injury and systemic cytokine release, in our cohort compared to previous studies.

5.1. Conclusions

The elevated IL-1β levels in the stenotic CAD group underscore its role in atherosclerosis and highlight its potential as a therapeutic target. The lack of significant differences in other inflammatory biomarkers suggests that inflammation in CAE may be more localized rather than systemic. Previous research has demonstrated elevated levels of endothelial activation markers, such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), E-selectin, and C-reactive protein, supporting the presence of localized vascular inflammation in CAE patients (20). However, to further elucidate the role of inflammation in CAE, additional studies with larger sample sizes and more precise classification of CAE by type and extent of ectasia are warranted.

5.2. Limitations

This study was conducted at a single center with a limited sample size, particularly in the CAE group, which may restrict the statistical power and generalizability of our findings. Although post-hoc analysis indicated adequate power for detecting differences in IL-1β levels, the analyses for hsCRP, IL-6, and TNF-α were likely underpowered. The limited sample size also precluded meaningful multivariable regression analyses. Future investigations with larger cohorts are required to achieve greater statistical power and enable multivariate analyses. Furthermore, we did not stratify CAE patients according to the severity or morphological characteristics of ectasia, which may have important implications for inflammatory profiles and advance our understanding of the condition.