1. Introduction

Chronic total occlusions (CTOs) account for approximately 20% of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography (1, 2), and advances in devices and operator expertise have markedly improved percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) success rates (3). The retrograde approach, a key modern technique, relies on careful selection of suitable collateral channels, guided by various scoring systems (4, 5). While prior investigations have extensively focused on septal and epicardial channels, the conus branch artery (CBA), an epicardial vessel, has often been overlooked despite its potential role in facilitating CTO PCI (5). The CBA, typically the first branch of the right coronary artery (RCA) and a vital conduit to the right ventricular outflow tract (4), is readily visualized via left anterior oblique (LAO) and right anterior oblique (RAO) projections on coronary angiography.

Studies have demonstrated that the CBA can be identified in 80.5 - 90% of patients, with a diameter of ≥ 1.5 mm in most cases (4). The CBA plays a multifaceted role during CTO PCI, serving as a vessel for wire or balloon anchoring and providing support and stabilization for the RCA guiding catheter (6). Furthermore, it contributes collateral circulation distal to the CTO, aiding in the revascularization of mid-RCA and left anterior descending artery (LAD) occlusions through epicardial connections and the Vieussens vascular ring (4, 6). Given its prevalence, accessibility, and unique contributions to collateral flow, the role of the CBA in facilitating CTO PCI warrants further investigation.

This report highlights two cases of left main (LM) CTO successfully treated using the retrograde PCI approach, involving collateral pathways including conus and septal branches, advanced guidewires, microcatheters, and contemporary drug-eluting stents (DES). These procedures culminated in full revascularization and complete relief of symptoms postoperatively, underscoring the clinical relevance of these approaches. This report is presented in compliance with the CARE case report guideline to ensure transparent and structured documentation of clinical details.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Retrograde Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of Left Main Chronic Total Occlusion via Conus Branch Collateral

2.1.1. Patient Information

A 65-year-old woman with long-standing exertional angina [Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) class III] presented with recurrent chest discomfort despite optimized anti-anginal therapy. She had hypertension and dyslipidemia but no diabetes or family history of premature coronary artery disease. She was a non-smoker with no prior myocardial infarction or revascularization. The patient refused coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) after multidisciplinary discussion and sought percutaneous revascularization due to disabling angina.

2.1.2. Clinical Findings

On examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable with unremarkable auscultation and no signs of heart failure. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) showed non-specific ST-T changes. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed normal left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction: Fifty-five percent) without regional wall motion abnormality.

2.1.3. Timeline

A summary of major diagnostic, interventional, and follow-up events in the first patient with LM CTO treated through the conus branch retrograde pathway is presented in Table 1.

| Date/Stage | Event |

|---|---|

| Week 0 | Admission for diagnostic angiography showing LM CTO; CABG advised but declined. |

| Week 1 | Scheduled PCI with retrograde strategy via conus branch collateral |

| Post‑PCI Day 1 | Successful revascularization achieved (TIMI 3 flow), discharged symptom‑free |

| Month 1 | Asymptomatic; ECG normal sinus rhythm; LVEF: Fifty-five percent |

| Month 3 | No angina; CCS I; Repeat echo unchanged; Good functional status |

2.1.4. Diagnostic Assessment

Selective coronary angiography demonstrated an ostial CTO of the LMCA. Antegrade visualization was poor due to proximal cap ambiguity. Retrograde filling of the LM via a small conus branch from the RCA was clearly identified and selected as the feasible collateral pathway. No other suitable septal or epicardial channels were available.

The diagnostic challenge was uncertain proximal cap morphology precluding safe antegrade entry. Given the patient’s CABG refusal, a retrograde PCI through the conus collateral was planned.

2.1.5. Therapeutic Intervention

Access: Bilateral femoral access was established. Antegrade guidance was attempted via the left femoral artery using an Extra Backup 3.5 (LAD) guiding catheter, but downstream visualization remained inadequate.

Retrograde Phase: A right femoral Amplatz 1 guiding catheter was used to engage the RCA and conus branch. Collateral channel navigation was achieved using a Sion Black wire supported by a Caravel 150 cm microcatheter. After crossing to the LM ostium, the Sion Black was replaced with GAIA II ASAHI for lesion penetration, then exchanged to an RG3 wire for externalization through the antegrade guiding catheter, accomplished without snaring.

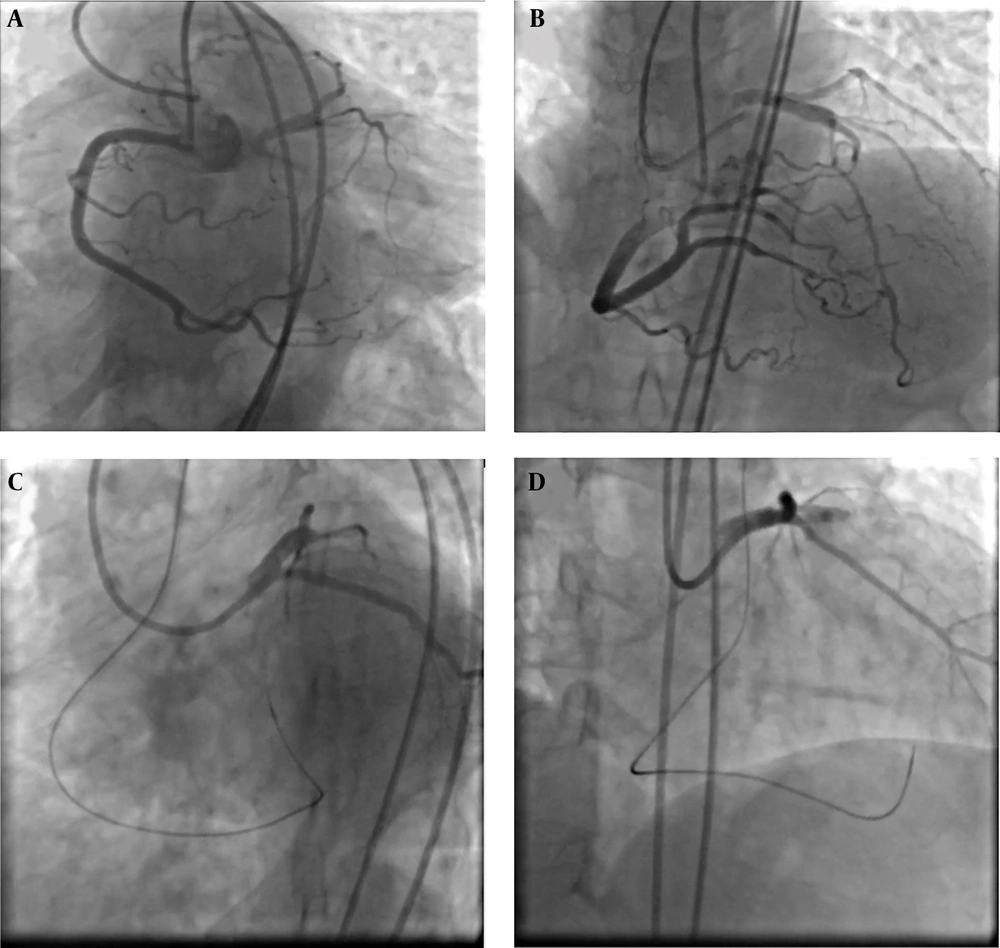

Lesion Preparation and Stenting: Sequential pre-dilatation was performed with a Ryurei 1.5×20 mm, Wilma NC 2.5×15 mm, and Accuforce 3.5×15 mm balloon. A Terumo Ultimaster 4.0×15 mm drug-eluting stent was deployed in the aorto-ostial LM segment. Final optimization and ostial flaring were achieved using a Conqueror 5.0×10 mm NC balloon (Figure 1).

Dual access injection showed left main chronic total occlusion (LM CTO) which was filled via retrograde approach through right coronary artery (A, B), then left main-left anterior descending artery (LM-LAD) was wired via conus branch of right coronary artery with black SION (C), then percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) on LM-LAD was done (D).

2.1.6. Follow-up and Outcomes

The angiographic result was excellent with TIMI grade 3 flow and full revascularization. There were no procedural complications, perforation, or no-reflow phenomena.

The patient reported immediate relief of symptoms. At follow-up:

Week 1: No angina, no ECG ischemic changes.

Month 1: Maintained symptom-free (CCS I).

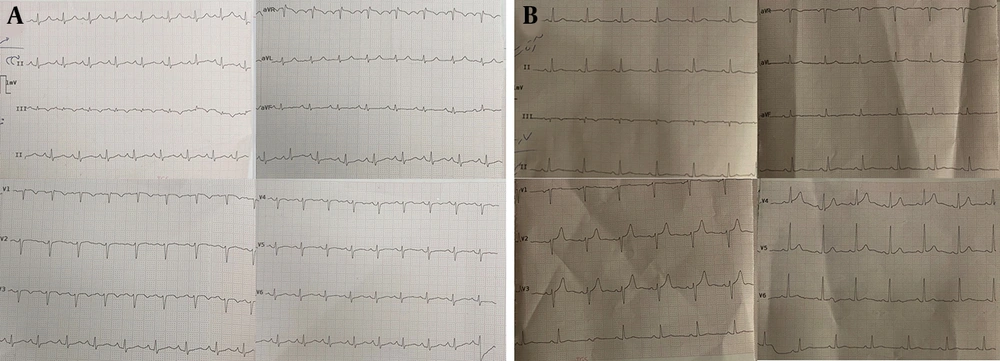

Month 3: Repeat ECG (Figure 2A) showed normal sinus rhythm and no ST-T changes; echocardiogram confirmed preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (55%), with no new wall motion abnormality. No adverse or unanticipated events occurred. Medication adherence was adequate as verified by pill counting and clinical interview.

Follow-up electrocardiograms at 3 months after successful retrograde revascularization of left main coronary artery chronic total occlusion (LMCA CTO). Case 1: Three-month ECG showing normal sinus rhythm with resolution of previous lateral ST-T changes and absence of ischemic abnormalities following retrograde PCI via the conus branch collateral (A). Case 2: Three-month ECG demonstrating stable sinus rhythm and restoration of normal repolarization pattern after retrograde LMCA CTO PCI performed through septal collaterals (B).

2.1.7. Novelty and Educational Value

This case demonstrates successful retrograde revascularization of an ostial LM CTO through a conus branch collateral; a route rarely used for LM lesions due to its limited caliber and risk of perforation. The patient achieved complete symptomatic recovery and avoided CABG, underlining the feasibility of this technically demanding approach when antegrade CTO PCI is precluded.

2.2. Retrograde Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of Left Main Chronic Total Occlusion via Septal Collateral

2.2.1. Patient Information

A 68-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, long-standing hypertension, and chronic stable angina (CCS class III) was referred for coronary angiography owing to recurrent exertional chest pain despite optimal medical therapy. He had no prior myocardial infarction, percutaneous intervention, or coronary bypass surgery. Given his refusal of CABG and failure of medical management, percutaneous revascularization was considered.

2.2.2. Clinical Findings

Physical examination revealed normal heart sounds without gallop or murmur and no signs of left ventricular failure. Baseline ECG showed lateral ST-T changes compatible with ischemia. Transthoracic echocardiography documented preserved left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction: Fifty-five percent) with mild concentric hypertrophy.

2.2.3. Timeline

A chronological overview of clinical presentation, procedural steps, and follow-up findings in the second case undergoing LMCA CTO PCI through septal collaterals is outlined in Table 2.

| Date/Stage | Event |

|---|---|

| Week 0 | Admission for diagnostic angiography showing LMCA CTO; CABG advised but declined. |

| Week 1 | Scheduled for retrograde PCI via septal collateral pathway. |

| Post‑PCI Day 1 | Successful revascularization (TIMI 3 flow); Symptom‑free, discharged stable |

| Month 1 | No angina, ECG normal sinus rhythm; LVEF: Fifty-five percent |

| Month 3 | CCS I, asymptomatic, repeat echo unchanged; Excellent functional status. |

2.2.4. Diagnostic Assessment

Coronary angiography revealed a heavily calcified CTO at the ostial segment of the LM artery, with proximal cap ambiguity and poor distal visualization. No suitable antegrade entry could be defined. Retrograde contrast injections demonstrated septal collateral channels from the LAD artery supplying the distal LM, allowing a feasible retrograde path. The key diagnostic challenge was inadequate antegrade visualization and proximal ambiguity, making a direct antegrade approach unsafe. Hence, a retrograde approach through septal branches was selected.

2.2.5. Therapeutic Intervention

Access: Bilateral femoral access was obtained. Antegrade guidance was provided via an Extra Backup 3.0 guiding catheter (left femoral). Retrograde access through the right femoral artery used a Judkins Right 4.0 guiding catheter to engage the septal collaterals.

Guidewires and microcatheters: Retrograde wiring was initiated using a Suoh 3 Asahi wire supported by a Caravel 150 cm microcatheter. Upon reaching the LM ostium, the Suoh 3 was exchanged for GAIA Second Next Asahi to penetrate the lesion. After successful advancement of the microcatheter, the wire was switched to a Gladius Mongo 300 cm for externalization, which smoothly passed through the Extra Backup 3.0 guiding catheter without need for snaring.

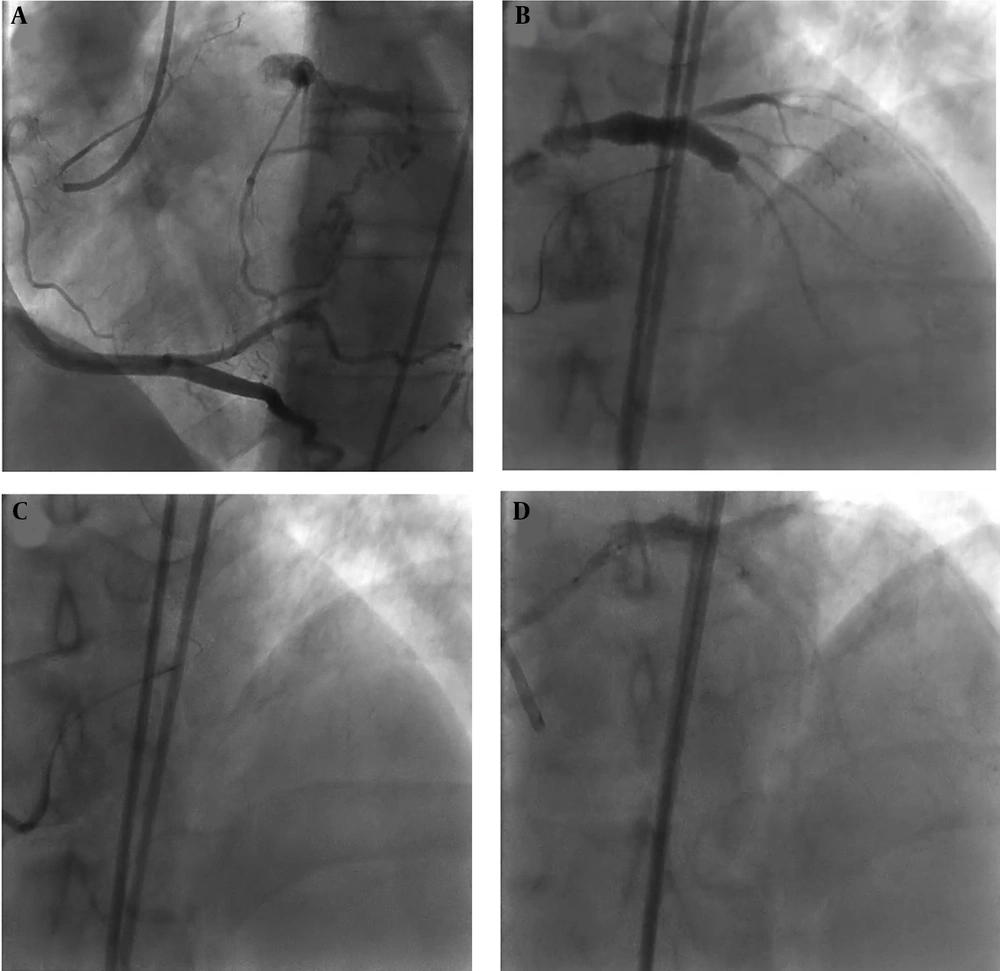

Lesion preparation and stenting: Sequential pre-dilatation was performed with a Ryurei Terumo 1.25 × 15 mm, Sapphire Orbus Neich 2.5 × 15 mm, and Accuforce Terumo 3.5 × 15 mm balloon. AXience Alpine Abbott 4.0 × 23 mm drug-eluting stent was deployed to cover the aorto-ostial LM segment, followed by final optimization and flaring using a Sapphire Orbus Neich 5.0 × 10 mm non-compliant balloon to achieve optimal apposition (Figure 3).

Dual access injection showed left main chronic total occlusion (LM CTO) which was filled via retrograde approach through right coronary artery (A, B), then left main-left anterior descending artery (LM-LAD) was wired via septal branches of right coronary artery with black SION (C), then percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) on LM-LAD was done (D).

2.2.6. Follow-up and Outcomes

Angiographic success was achieved with complete CTO recanalization and TIMI grade 3 flow. There were no procedural complications such as dissection, perforation, or hemodynamic instability.

At follow-up:

Week 1: Symptom free; ECG showed restoration of normal ST-T segments.

Month 1: Maintained CCS I; LVEF: Fifty-five percent, no ischemic ECG changes.

Month 3: Stable functional capacity; repeat ECG (Figure 2B) remained normal; no target lesion restenosis or adverse events recorded.

Adherence to dual antiplatelet therapy was confirmed by pill counting and clinical interview. No adverse or unanticipated events occurred.

2.2.7. Novelty and Educational Value

This case highlights successful retrograde left main CTO PCI using septal collateral communication, an extremely uncommon pathway for LM lesions because of complex channel tortuosity and risk of septal perforation. The patient achieved complete revascularization despite CABG refusal, underscoring that contemporary retrograde equipment and strategy, when carefully selected, can yield durable outcomes in otherwise inoperable LM CTO.

A comparative summary of baseline characteristics, procedural details, and outcomes of both cases is presented in Table 3.

| Parameter | Case 1- CBA | Case 2-Septal Collateral (LAD Septal) |

|---|---|---|

| Age/sex | 65/female | 68/male |

| Risk factors | Hypertension, dyslipidemia | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension |

| Functional class (pre PCI) | CCS III | CCS III |

| Dominant coronary system | Right dominant | Right dominant |

| Collateral route | Conus branch from RCA | Septal channel from LAD |

| Wire strategy | Sion black → GAIA II → RG3 | Suoh 3 → GAIA second next → glad us mongo |

| Microcatheter | Caravel 150 cm | Caravel 150 cm |

| Guiding catheters | Extra backup 3.5 (LM); Amplatz 1 (RCA) | Extra backup 3.0 (LM); Judkins right 4.0 (RCA) |

| Pre dilatation balloons | Ryurei 1.5 × 20 mm; Wilma 2.5 × 15 mm; Accuforce 3.5 × 15 mm | Ryurei 1.25 × 15 mm; sapphire 2.5 × 15 mm; Accuforce 3.5 × 15 mm |

| Stent type and size | Ultimasterterumo 4.0 × 15 mm | Xience alpine abbott 4.0 × 23 mm |

| Post dilatation balloon | Conqueror 5.0 × 10 mm | Sapphirerbus Neich 5.0 × 10 mm |

| TIMI flow (After PCI) | Grade 3 | Grade 3 |

| LV Ejection Fraction (Follow up) | 55 % | 55 % |

| CCS improvement (post PCI) | Class III → I | Class III → I |

| ECG follow up (3 months) | Normal sinus rhythm; No ischemic changes | Normal sinus rhythm; No ischemic changes |

| Outcome at 3 months | Symptom free; Good functional capacity | Symptom free; Good function |

Abbreviations: CBA, conus branch collateral; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; ECG, electrocardiogram; LV, left ventricular; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society.

3. Discussion

Chronic total occlusions remain among the most challenging targets in PCI due to their intrinsic procedural complexities and the heightened risk of technical failure (7). Over the past decades, however, significant advancements in device technology, refinement of procedural techniques, and increased operator experience have collectively translated into a substantial rise in success rates for CTO PCI (7). One of the pivotal factors in successful CTO intervention is the assessment and strategic utilization of collateral circulation.

Collateral arteries play a key role in preserving myocardial viability by maintaining perfusion in regions subtended by an occluded vessel (8-10). Their functional significance extends to safeguarding the myocardium from ischemic injury during acute coronary insufficiency, thereby providing a critically important temporal “bridge” for revascularization (6, 8, 9, 11). This is particularly relevant in LMCA disease. The LMCA supplies approximately 75% of the left ventricular myocardium in right-dominant circulation and up to 100% in left-dominant circulation, magnifying the hemodynamic consequences of its stenosis or occlusion. Chronic total occlusion of the LMCA is exceptionally rare and typically occurs only in patients with a dominant RCA supported by well-developed collaterals (12).

Understanding the origin of collateral flow to a chronically occluded vessel is critical in procedural planning. McEntegart et al. reported that in cases of LAD artery CTO, collateral supply originated from the posterior descending artery (PDA) in 52.3% of patients, the right ventricular branch in 26.8%, and the conus branch in 5.9% (6). The conal branch artery (CBA), also known as the conus branch or infundibular artery, is the first branch of the RCA in approximately half of the population (13, 14). In the other half, CBA arises independently from a separate ostium within the right aortic sinus of Valsalva; in such cases, it is termed the “third” coronary artery (13, 14). This vessel supplies the right ventricular outflow tract, and its visualization in coronary angiography is best achieved in LAO and RAO projections. Although its anatomical presence is anticipated in nearly 90% of individuals, connections from the CBA to distal vessel segments are relatively uncommon — being noted in only 27.3% of CTO cases in one series and as low as 2.6% in another (4, 6).

From an interventional perspective, the CBA can serve several potential roles in CTO PCI. It may provide a stable anchor for guiding catheter positioning, facilitate passage of wires or balloons, and, in certain cases, act as a conduit for retrograde access to the distal true lumen of an occluded vessel (4, 6). This characteristic becomes particularly valuable in complex lesions where conventional antegrade strategies fail. A persistent challenge in CTO PCI is the inability to direct the guidewire into the true lumen, which frequently results in procedural failure (15, 16). Retrograde techniques — using channels such as septal collaterals, epicardial collaterals, or the CBA — have significantly improved crossing success, especially in lesions resistant to antegrade approaches.

The evolution of the retrograde strategy has been instrumental in increasing CTO PCI success rates from under 70% to approximately 90% in expert centers (4, 17). Despite its benefits, retrograde PCI is associated with longer procedural times, greater contrast volume, prolonged fluoroscopy exposure, and a higher risk of periprocedural complications relative to antegrade methods (17). Meta-analyses consistently demonstrate that antegrade PCI offers superior overall procedural and technical success rates, along with lower incidences of major adverse cardiac events, all-cause mortality, and myocardial infarction (17). Nevertheless, antegrade techniques cannot address all anatomical complexities — retrograde access remains indispensable in challenging subsets, especially in patients with ostial occlusions, ambiguous proximal caps, tortuous anatomy, or prior failed antegrade attempts.

Insights from Meng et al. provide an important perspective on the utility of the CBA in retrograde CTO PCI. In their study, procedural success rates exceeded 95%, independent of whether CBA was utilized. Interestingly, the group in which CBA was employed had significantly higher J-CTO scores, indicating greater lesion complexity, and showed a higher prevalence of retrograde techniques (4). This group also exhibited longer fluoroscopy and total procedural times, consistent with the procedural demands of treating more complex anatomy. Importantly, the similarity in success rates between the CBA and non-CBA groups suggests that CBA utilization does not compromise procedural efficacy despite being reserved for challenging scenarios. These observations highlight the potential of the CBA as a valuable adjunct in CTO PCI, especially when septal or epicardial collaterals are unsuitable or absent (4).

The selection of an optimal collateral pathway is multifactorial, driven primarily by lesion-specific characteristics, angiographic anatomy, and operator experience. While the routine use of the CBA appears limited by its anatomical variability and relative rarity of suitable distal connections, its role in select cases can be significant. This underscores the need for further investigation to identify the clinical and angiographic contexts in which CBA utilization yields the greatest procedural and long-term benefits. Future research should aim to delineate patient selection criteria, assess the impact of CBA use on long-term outcomes such as target vessel patency and patient quality of life, and optimize technical strategies for its integration into contemporary CTO PCI practice (4, 17, 18).

3.1. Patient Perspective

Both patients expressed satisfaction with PCI results after refusing CABG and reported improved functional capacity during follow-up.

3.2. Learning Points

1. The total chronic occlusion of the LMCA is extremely rare but can be successfully treated percutaneously using contemporary retrograde techniques.

2. Proper selection of collateral pathway, conus branch or septal, is pivotal for safe and effective guidewire crossing when antegrade strategies fail.

3. In patients refusing CABG, retrograde PCI can achieve full revascularization and symptomatic relief without adverse events.

4. Careful procedural planning and use of dedicated guidewires and microcatheters are essential for success in complex LMCA CTO lesions.

3.3. Conclusions

In summary, both antegrade and retrograde strategies remain essential components of the CTO PCI toolkit. Antegrade remains the default initial approach due to its efficiency, safety, and resource profile, while retrograde — often via septal or less commonly CBA pathways — remains critical for anatomically complex lesions and failed antegrade attempts. As device technology and operator expertise continue to evolve, the ability to individualize strategy selection, including the judicious use of CBA collaterals, will be central to improving outcomes for patients with complex CTOs.