1. Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), especially in those with advanced kidney dysfunction or on long-term dialysis (1). Mortality rates in individuals receiving kidney replacement therapies are significantly higher compared to their age- and sex-matched peers (2). According to the 2024 Annual Data Report (ADR) on ESRD, CVDs are responsible for more than half of all deaths in patients receiving hemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD) (3). The association between CKD and cardiovascular mortality is markedly influenced by vascular alterations, in particular atherosclerosis and vascular calcification (VC) (4).

The presence of carotid plaques, especially calcified ones, can be a predictor of new cardiovascular events and cardiovascular mortality in patients undergoing dialysis (5). Intima-media thickness (IMT), the number of plaques, and arterial remodeling are considered key indicators of accelerated atherosclerosis (6). Carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) is widely recognized as an important measure for subclinical carotid atherosclerosis, aiding in the prediction of CVD and enhancing cardiovascular risk assessment (7, 8). Monitoring CIMT in conjunction with other atherosclerosis risk factors may yield valuable prognostic information regarding the risk of CVD in dialysis patients (9).

The choice of dialysis modality — whether HD or PD — may further impact cardiovascular risk factors and the progression of atherosclerosis (10). As part of ongoing efforts to better understand vascular remodeling among dialysis patients, several studies have compared the prevalence and severity of CIMT between HD and PD patients. While some studies suggest no significant difference in CIMT and plaque scores between PD and HD (11), others report higher CIMT (12) and carotid plaque presence (13) in HD. On the other hand, longer-term research has shown that PD patients can have significantly higher CIMT than those on HD (14). Additionally, a study involving ESRD patients undergoing PD revealed a notable prevalence of carotid artery calcifications (CACs), highlighting a clear association between longer durations of PD and the presence of CACs (15).

2. Objectives

Given the conflicting findings and the limited number of studies directly comparing CAC in patients undergoing HD versus PD, our cross-sectional study aims to provide enhanced insights. By evaluating both the prevalence and severity of CAC among patients undergoing regular dialysis sessions, we aim to clarify the potential influence of dialysis modality on VC and its related cardiovascular risks.

3. Methods

A comparative cross-sectional study comparing coronary artery atherosclerosis, stenosis, and calcification among dialysis-dependent patients undergoing either HD or PD was conducted from January to May 2024. This study was conducted at dialysis centers affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in Shiraz, located in southern Iran. Furthermore, the study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences under the ethics code IR.SUMS.MED.REC.1402.258.

3.1. Participants

Eligible participants were dialysis-dependent patients aged 18 years and older who had been undergoing regular dialysis sessions for at least six months. Patients meeting any of the following criteria were excluded from the study: (1) History of acute infection in the last three months, (2) history of peritonitis in the last three months, (3) acute coronary artery disease (e.g., MI, unstable angina, ACS), cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease after starting dialysis, (4) unstable clinical condition, (5) malignancy, (6) liver cirrhosis, (7) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and (8) systemic inflammatory diseases. “Sample size was calculated using the standard formula for comparing two independent groups with α = 0.05 and power = 80%, resulting in a minimum requirement of 16 patients per group.” “Patients were first screened based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligible individuals were then approached, informed about the study, and written informed consent was obtained prior to enrollment.” Two groups of patients who were scheduled for HD or PD during the designated study period were systematically identified. A random number generator was employed to create two distinct sets, each consisting of twenty random numbers, allowing for the selection of patients for inclusion in the study. “Although random numbers were initially generated to guide patient selection, the final sampling process is better characterized as convenience sampling due to feasibility constraints.”

Those who declined to participate or did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria were subsequently excluded. In the HD subgroup, two candidates declined participation, and two were disqualified due to exclusion criteria. In the PD subgroup, one candidate declined to participate, and three were excluded based on exclusion criteria. Ultimately, sixteen patients from each comparison group proceeded to the data collection stage. All participants provided written informed consent to take part in the study.

3.2. Data Collection

Baseline information, including demographic variables (age and sex), comorbidities, underlying causes of kidney failure, and duration of dialysis, was collected from patient records and interviews. These data were used to compare HD and PD groups, ensuring appropriate sampling and exchangeability. Serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, albumin, parathyroid hormone (PTH), 25-hydroxyvitamin D (vitamin D3), triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and C-reactive protein (CRP) were measured and compared across two study groups.

Carotid artery atherosclerosis was assessed using Doppler ultrasound in both carotid arteries. This procedure was carried out by an experienced radiologist with the patient positioned supine, neck hyperextended, and rotated to the opposite side. The interval between the collection of baseline data and the ultrasound evaluation should be less than two months. The following parameters were measured.

3.2.1. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness

The CIMT refers to a low-echogenicity gray band that does not extend into the arterial lumen and signifies the distance between the luminal-intimal boundary and the medial-adventitial boundary. Measurements were taken at three distinct points along both common carotid arteries, at the bifurcation, and the proximal internal carotid artery, with the average value reported.

3.2.2. Carotid Stenosis

This condition is characterized by a focal thickening that is at least 50% greater than that of the surrounding arterial wall, or by the presence of a distinct hyperechoic region within the arterial wall.

3.2.3. Calcified Plaque

The presence of a calcified plaque is determined by observing acoustic shadowing caused by the plaque within the arterial wall. The radiologist performing carotid ultrasonography was blinded to the dialysis modality of the participants.

To further delineate the cardiovascular risk profile associated with dialysis modality, we analyzed advanced and novel lipid-related indices, including total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein (TC/HDL)-C ratio, LDL-C/HDL-C ratio, remnant cholesterol, and Lipoprotein Combine Index (LCI).

3.3. Statistical Methods

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics [Release 27.0.1.0, SPSS Inc., 2020 (licensed institutional version)]. Descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation [SD, or median and interquartile range (IQR)], were used for quantitative data, while relative frequencies were reported for qualitative data. Non-parametric tests were used due to the small sample size. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative variables between groups, and Fisher’s exact test was used for qualitative comparisons. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Additionally, stepwise multiple linear and logistic regression analyses were used to identify independent predictors of CIMT, carotid stenosis, and calcified plaque. Variables with a P-value of less than 0.25 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariable models. Lipid profile variables (LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides, and total cholesterol) with a P-value < 0.25 in univariate analyses were considered for inclusion in multivariable regression models. The statistical analyst was blinded to the dialysis modality of the participants.

4. Results

4.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 32 patients participated in the study, comprising 16 individuals undergoing maintenance HD (n = 16) and 16 individuals receiving PD (n = 16). The median age was higher in the HD cohort compared to the PD group (60 [IQR: 32 - 70] vs. 50.5 [IQR: 39.3 - 62.8] years), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.299). A predominance of male patients was observed in the HD group (75.0%) compared with the PD cohort (56.3%), which was also not statistically significant (P = 0.264).

The underlying causes of kidney failure were similarly distributed across the two groups, with no significant intergroup differences noted. Hypertension was present in 75.0% of the HD group compared to 62.5% of the PD group (P = 0.446). Type 2 diabetes mellitus occurred in 37.5% of the HD group versus 25.0% in the PD group (P = 0.446). Glomerulonephritis was found in 6.3% of the HD group and none in the PD group (P > 0.99), while nephrolithiasis was also present in 6.3% of the HD group and absent in the PD group (P > 0.99). Although the dialysis duration was longer in the HD cohort, with a median of 6.5 years (IQR: 3 - 10), compared to 4.0 years (IQR: 1.25 - 7.0) in the PD group, this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.110). A comprehensive summary of these demographic and clinical features is presented in Table 1, and a visual overview is shown in Supplementary File, Figure S1 in Supplementary File.

4.2. Biochemical Profile

Assessment of laboratory biochemical parameters revealed no statistically significant differences between the HD and PD groups regarding serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, albumin, PTH, vitamin D3, triglycerides, LDL, HDL, or CRP status. Conversely, total serum cholesterol levels were significantly elevated in patients undergoing PD compared to those receiving HD [179 mg/dL (IQR: 151.3 - 204.5) vs. 120 mg/dL (IQR: 95.5 - 148.3), P < 0.001]. All other biomarkers demonstrated comparable distributions across groups. A detailed comparison of biochemical profiles between the two cohorts can be found in Table 1, and Supplementary File, Figure S2 in Supplementary File illustrates the distribution of selected markers.

| Variables | Total (N = 32) | HD (N = 16) | PD (N = 16) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.264 b | |||

| Male | 21 (65.6) | 12 (75.0) | 9 (56.3) | |

| Female | 11 (34.4) | 4 (25.0) | 7 (43.8) | 0.299 c |

| Age (y) | 57 [38 - 69] c | 60 [32 - 70] | 50.5 [39.3 - 62.8] | |

| Hypertension | 0.446 b | |||

| Yes | 22 (68.8) | 12 (75.0) | 10 (62.5) | |

| No | 10 (31.3) | 4 (25.0) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Type 2 diabetes | 0.446 b | |||

| Yes | 10 (31.3) | 6 (37.5) | 4 (25.0) | |

| No | 22 (68.8) | 10 (62.5) | 12 (75.0) | |

| Kidney stones | > 0.99 b | |||

| Yes | 1 (3.1) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | |

| No | 31 (96.9) | 15 (93.8) | 16 (100.0) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | > 0.99 b | |||

| Yes | 1 (3.1) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | |

| No | 31 (96.9) | 15 (93.8) | 16 (100.0) | 0.110 c |

| Dialysis vintage (y) | 5 [2 - 9.5] c | 6.5 [3 - 10] | 4.0 [1.25 - 7.0] | |

| Biochemical profile | ||||

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.6 [8.3 - 9.08] | 8.6 [8.3 - 9.15] | 8.6 [8.35 - 9.0] | 0.809 c |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.65 [3.42 - 3.9] | 3.7 [3.5 - 3.9] | 3.6 [3.3 - 3.9] | 0.381 c |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4.8 [3.95 - 5.55] | 4.85 [4.35 - 5.37] | 4.75 [3.3 - 5.97] | > 0.99 c |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 110 [66.5 - 250.25] | 122 [62.75 - 260] | 103 [75.5 - 231] | 0.616 c |

| Vitamin D3 (ng/mL) | 28 [26.25 - 36.5] | 29.5 [27 - 41.5] | 28 [23.5 - 30] | 0.160 c |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 120 [85.75 - 158] | 114 [76.5 - 166] | 126 [94 - 147.5] | 0.897 c |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 151 [115.25 - 184.25] | 120 [95.5 - 148.25] | 179 [151.25 - 204.5] | < 0.001 c |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 88.5 [70 - 98.75] | 86 [62.5 - 100] | 91 [70.75 - 94.75] | 0.809 c |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 46 [35 - 50] | 46 [36 - 51.5] | 45 [34.25 - 49.75] | 0.423 c |

| CRP status | > 0.99 b | |||

| Negative | 31 (96.9) d | 16 (100.0) | 15 (93.8) | |

| Positive | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) |

Abbreviations: HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PTH, parathyroid hormone; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or median [interquartile range (IQR)].

b Fisher’s exact test.

c Mann-Whitney U test.

d Count (%).

4.3. Carotid Artery Calcification and Stenosis

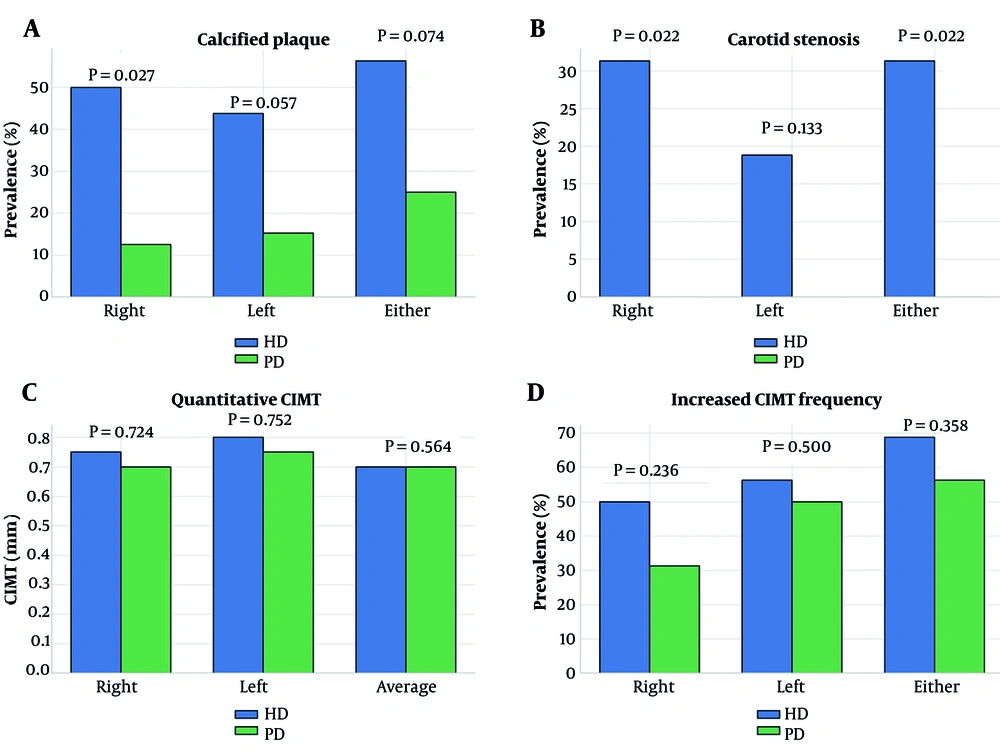

The prevalence of CAC was significantly greater among patients undergoing HD compared to those receiving PD. In the right carotid artery, calcified plaques were identified in 50.0% of HD patients versus 12.5% of those undergoing PD (P = 0.027). A similar trend was observed on the left side (43.8% vs. 15.2%, P = 0.057). Furthermore, when examining the presence of calcified plaque in either carotid artery, 56.3% of HD patients were affected, compared to 25.0% of those undergoing PD (P = 0.074).

Carotid artery stenosis was observed exclusively in the HD cohort. Right-sided stenosis was significantly more frequent in HD patients (31.3%) compared to none in the PD group (P = 0.022). Although left-sided stenosis was numerically more common in HD (18.8% vs. 0%), this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.133). However, combined stenosis (right or left carotid artery) remained significantly more prevalent among HD patients (P = 0.022).

Quantitative assessment of CIMT revealed no significant differences between groups. The median average CIMT was 0.7 mm [IQR: 0.52 - 0.89] in HD and 0.7 mm [IQR: 0.65 - 0.88] in PD (P = 0.564). Side-specific CIMT values for right (P = 0.724) and left (P = 0.752) carotid arteries were also statistically similar. Furthermore, the frequency of increased CIMT (> 0.9 mm) did not significantly differ between modalities across any location. A full overview of carotid calcification, stenosis, and CIMT measurements is provided in Table 2, with key imaging parameters illustrated in Figure 1.

| Locations/Variables | Total (N = 32) | HD (N = 16) | PD (N = 16) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right carotid artery | ||||

| Calcified plaque | 31.3 | 50.0 | 12.5 | 0.027 b |

| Stenosis | 15.6 | 31.3 | 0.0 | 0.022 b |

| Increased CIMT | 40.6 | 50.0 | 31.3 | 0.236 b |

| CIMT (mm) | 0.7 [0.6 - 0.8] | 0.75 [0.13 - 0.8] | 0.7 [0.6 - 0.875] | 0.724 c |

| Left carotid artery | ||||

| Calcified plaque | 28.1 | 43.8 | 15.2 | 0.057 b |

| Stenosis | 9.4 | 18.8 | 0.0 | 0.133 b |

| Increased CIMT | 53.1 | 56.3 | 50.0 | 0.500 b |

| CIMT (mm) | 0.8 [0.625 - 0.9] | 0.8 [0.7 - 0.9] | 0.75 [0.6 - 0.95] | 0.752 c |

| Either carotid artery | ||||

| Calcified plaque | 40.6 | 56.3 | 25.0 | 0.074 b |

| Stenosis | 15.6 | 31.3 | 0.0 | 0.022 b |

| Increased CIMT | 62.5 | 68.8 | 56.3 | 0.358 b |

| Average CIMT (mm) | 0.7 [0.65 - 0.89] | 0.7 [0.52 - 0.89] | 0.7 [0.65 - 0.88] | 0.564 c |

Abbreviations: HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; CIMT, carotid intima-media thickness.

a Values are expressed as percentage or median [interquartile range (IQR)].

b Fisher’s exact test.

c Mann-Whitney U test.

Carotid vascular alterations in patients undergoing hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD): A, prevalence of carotid artery calcified plaques (right, left, or either artery); B, frequency of carotid artery stenosis; C, quantitative carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) measurements (right, left, and average); D, percentage of patients with increased CIMT (> 0.9 mm). Statistically significant P-values are indicated above the relevant comparisons (HD: Blue and PD: Green).

4.4. Multivariable Regression Analysis

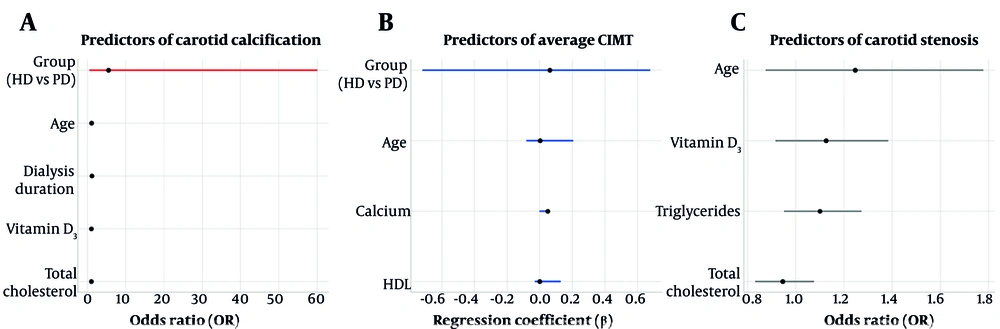

Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified age as the only significant independent predictor of CAC. Specifically, each one-year increase in age was associated with a 7.9% rise in the odds of having calcified carotid plaques [odds ratio (OR) = 1.079; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.012 - 1.151; P = 0.021]. In contrast, dialysis modality, duration of dialysis, serum vitamin D3, and total cholesterol levels were not significantly associated with CAC presence.

Linear regression analysis examining average CIMT did not reveal any significant associations with the studied covariates, including age, dialysis modality, serum calcium, and HDL cholesterol.

Similarly, logistic regression analysis for carotid artery stenosis demonstrated that none of the evaluated clinical or biochemical parameters — including age, vitamin D3, triglycerides, and total cholesterol — served as significant independent predictors. A detailed overview of the multivariable regression models is presented in Table 3, with key results visualized in Figure 2.

| Models/Variables | OR/β | 95% CI (Lower - Upper) | SE | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAC (logistic regression) | ||||

| Group (ref: PD) | 5.497 | 0.503 - 60.049 | 1.220 | 0.162 |

| Age (y) a | 1.079 | 1.012 - 1.151 | 0.033 | 0.021 |

| Dialysis duration (y) | 1.147 | 0.895 - 1.469 | 0.126 | 0.278 |

| Vitamin D3 (ng/mL) | 1.023 | 0.971 - 1.078 | 0.027 | 0.395 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1.015 | 0.985 - 1.046 | 0.015 | 0.333 |

| Average CIMT (linear regression) | ||||

| Group (ref: PD) | 0.063 | -0.719 - 0.679 | 0.069 | 0.372 |

| Age (y) | 0.003 | -0.080 - 0.206 | 0.002 | 0.103 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 0.050 | -0.001 - 0.008 | 0.039 | 0.205 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 0.001 | -0.029 - 0.130 | < 0.001 | 0.181 |

| Carotid stenosis (logistic regression) | ||||

| Age (y) | 1.247 | 0.875 - 1.778 | 0.181 | 0.223 |

| Vitamin D3 (ng/mL) | 1.126 | 0.916 - 1.384 | 0.105 | 0.261 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 1.100 | 0.951 - 1.273 | 0.074 | 0.199 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.946 | 0.832 - 1.076 | 0.066 | 0.396 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; β, regression coefficient; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error; CAC, carotid artery calcification; PD, peritoneal dialysis (reference category); CIMT, carotid intima-media thickness; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

a Significant results.

Multivariable regression models identifying predictors of carotid vascular outcomes in dialysis patients: A, forest plot showing odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for independent predictors of carotid artery calcification (CAC) – age emerged as a significant predictor (P = 0.021); B, linear regression coefficients (β) and 95% CIs for average carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT, none of the variables was significant); C, ORs for carotid artery stenosis, with all predictors remaining non-significant. Red markers indicate statistically significant predictors (P < 0.05; abbreviations: HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis).

4.5. Emerging Lipid-Profile Ratios and Indices in Relation to Dialysis Modality

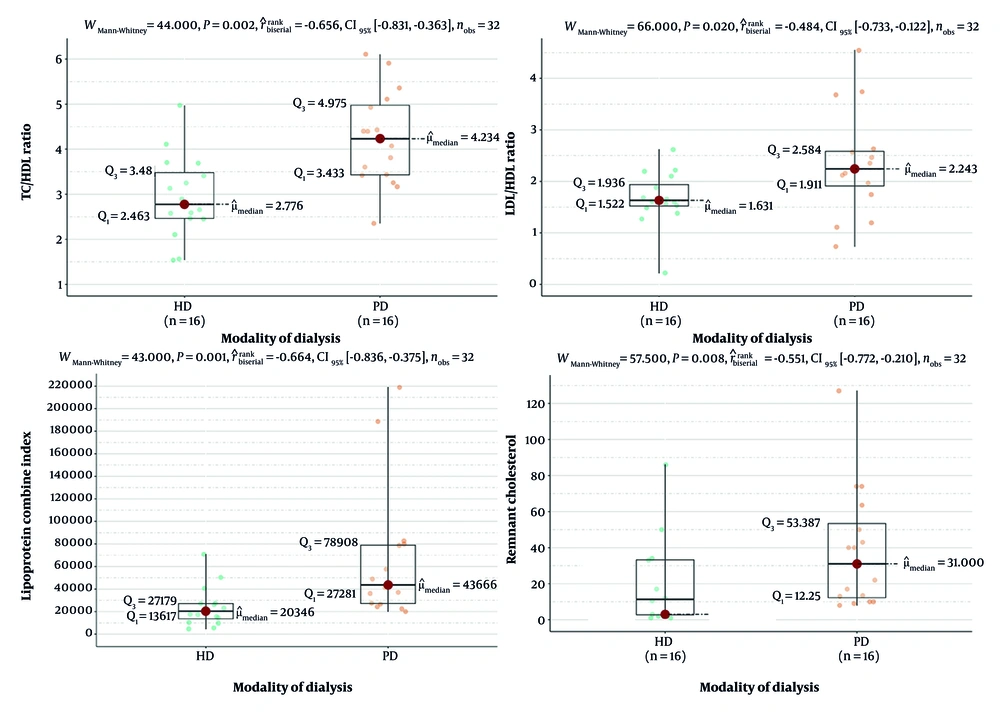

All four parameters demonstrated significantly higher median values in PD patients compared to HD counterparts. Notably, the median TC/HDL-C ratio was 4.234 in PD vs. 2.776 in HD patients (P = 0.002), while the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio was 2.243 in PD vs. 1.631 in HD (P = 0.020). Similarly, the LCI (median: 43666 vs. 20346, P = 0.001) and remnant cholesterol (median: 31.0 vs. 3.0, P = 0.008) were significantly elevated in PD patients. These findings suggest a more atherogenic lipid profile among PD patients, as reflected by both traditional and nontraditional lipid markers, despite comparable LDL and HDL levels (Figure 3).

Comparison of lipid-based atherogenic indices between hemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients. Box-and-whisker plots demonstrate significantly higher levels of total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein ratio (TC/HDL), low-density lipoprotein to high-density lipoprotein ratio (LDL/HDL), remnant cholesterol, and Lipoprotein Combine Index (LCI) in PD patients compared to HD patients. These findings indicate a more atherogenic lipid profile in the PD group despite their lower prevalence of carotid artery calcification (CAC) and stenosis. All comparisons were statistically significant (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test; abbreviation: CI, confidence interval).

5. Discussion

This study provides a comparative evaluation of CAC, carotid artery stenosis, and CIMT in patients undergoing HD versus PD, aiming to elucidate differences in vascular pathology between these two dialysis modalities. Our findings indicate a significantly greater burden of VC and stenosis among HD patients, with calcified plaques present in 50.0% of the right carotid arteries in HD patients compared to 12.5% in PD patients (P = 0.027), and right-sided carotid stenosis exclusively present in HD patients (31.3%, P = 0.022). These findings underscore the heightened vascular risk in HD patients, even in the absence of marked differences in conventional cardiovascular risk factors. These results align with existing literature, which identifies HD patients as being at greater risk for VC compared to their PD counterparts (13, 16-19).

In contrast, CIMT did not significantly differ between groups, with both cohorts demonstrating a median average CIMT of 0.7 mm. Although CIMT is a well-recognized surrogate marker for early atherosclerosis (20), its inability to differentiate between HD and PD patients in this study suggests that it may not adequately reflect the severity or type of vascular changes associated with dialysis-related pathophysiology. The CIMT quantifies the thickness of the intima and media layers of the carotid artery, whereas observing CAC indicates more advanced atherosclerotic changes and may develop independently of changes in CIMT (21, 22). This discrepancy underscores the complexity of atherosclerosis in patients undergoing dialysis and highlights the necessity for a comprehensive assessment utilizing multiple imaging modalities. This dissociation has been noted in prior literature, where CIMT and CAC reflect different phases or manifestations of vascular atherosclerosis (12). Furthermore, the relatively small sample size may have constrained the ability to detect subtle differences in CIMT between the groups.

Although all studies indicate that dialysis patients have higher CIMT compared to non-dialysis populations (12, 14), some studies report higher CIMT in PD patients compared to HD patients (14, 23, 24), while others find no significant differences between dialysis modalities (11, 25), and some report increased CIMT in HD patients (12, 13). Variations in race, sample size, selection criteria, and research methodology might partially explain these discrepancies (14). In our study, multivariable analyses also reflected no association between dialysis modality and CIMT. Age was the only significant predictor of CAC (OR = 1.079; P = 0.021), reaffirming its role as a cumulative risk factor for VC. Hojs reported a significant positive correlation between the number of plaques and age in HD patients. Age-related changes in vascular structure and function, coupled with the cumulative impact of dialysis-related factors, contribute to this association (26). Notably, neither serum calcium, phosphorus, PTH, vitamin D3, nor total cholesterol — apart from the significantly higher cholesterol levels in PD patients — were independently associated with either CAC or CIMT, reinforcing that VC in ESRD is multifactorial and not solely attributable to traditional lipid or mineral metabolism abnormalities.

Despite higher total cholesterol levels among PD patients, this did not translate into increased VC, which may be due to the relatively more stable hemodynamic profile in PD, preserved residual kidney function (RKF), and lower inflammatory burden. It is also possible that the continuous nature of PD allows for better long-term blood pressure and volume management, potentially mitigating the impact of hyperlipidemia. The use of glucose-based dialysis solutions and continuous peritoneal protein leakage during PD may contribute to a more atherogenic serum profile, potentially leading to more severe dyslipidemia compared to HD (10). Future research should further explore the impact of dyslipidemia on vascular health and cerebrovascular events in both PD and HD patients.

Mechanistically, the pro-calcific environment in HD may be driven by several dialysis-related factors that are more pronounced in HD compared to PD. These factors include (1) repetitive exposure to non-biocompatible dialysis membranes during HD, leading to chronic low-grade inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, as evidenced by release of reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytokines [e.g., interleukin [IL]-1, 6, 8, 12, 13, TNF-alpha, monocyte chemoattractant peptide-1], and interferons (IFN), as well as complement activation through alternative pathway (27); (2) greater fluctuations in blood pressure and volume in HD patients versus those undergoing PD, which happens to induce CIMT increment; and (3) relatively lower preserved RKF among HD patients, which plays a crucial role in fluid and electrolyte balance, better nutritional status, lowering inflammatory burden, and improving cardiovascular outcomes (12). Additionally, HD patients are more likely to be prescribed calcium-based phosphate binders, which have been linked to an elevated risk of arterial calcification (28).

This study adds to the growing body of evidence that dialysis modality has a differential impact on vascular pathology, with HD patients experiencing more severe calcific changes. Given the limitations of CIMT in differentiating vascular risk, especially in dialysis populations, routine assessment of CAC using sensitive imaging modalities may be warranted in HD patients. Ultimately, this reinforces the need for dialysis-modality-specific strategies in cardiovascular risk stratification and intervention. Understanding these differences is vital for personalizing treatment strategies, such as using non-calcium-based phosphate binders in HD or prioritizing PD in patients at high risk for VC.

In addition to structural vascular changes, we further evaluated atherogenic lipid indices, including TC/HDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C ratios, remnant cholesterol, and the LCI. Interestingly, these indices were significantly higher among PD patients, suggesting a more atherogenic lipid profile in this group despite their lower burden of carotid calcification and stenosis. This apparent paradox underscores the multifactorial nature of cardiovascular risk in dialysis patients and suggests that biochemical markers and imaging may reflect distinct pathological mechanisms.

Recent data support this dissociation. Hu et al. demonstrated a non-linear relationship between the Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP) and all-cause mortality in PD patients, with improved survival observed at moderate AIP levels but increased mortality beyond a threshold of 0.63. Our findings are consistent with this “reverse epidemiology” phenomenon, where elevated lipid indices may reflect better nutritional status or lower inflammatory burden. Nonetheless, the higher LCI and remnant cholesterol levels observed in PD patients warrant further exploration as potential targets for cardiovascular risk stratification and intervention (16).

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights key differences in vascular pathology between dialysis modalities. The HD patients exhibited significantly higher rates of CAC and stenosis compared to PD patients, despite no significant differences in CIMT or most biochemical parameters. These findings suggest that VC is more pronounced and possibly more advanced in HD patients, and that CIMT alone may be insufficient to capture this risk.

Age remains a critical, non-modifiable risk factor for VC, underscoring the need for early detection and targeted intervention in older dialysis patients. The results emphasize the value of multimodal vascular assessment in ESRD, combining CIMT with imaging techniques capable of detecting medial calcification.

Clinical management should incorporate dialysis-specific cardiovascular risk assessments and consider the use of non-calcium-based phosphate binders, anti-inflammatory strategies, and preservation of RKF, particularly in HD patients. These insights could inform clinical decision-making and contribute to the development of personalized care pathways aimed at mitigating cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the ESRD population.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

Despite the robust findings, this study has notable limitations. The sample size was relatively small (n = 32), which may have reduced the statistical power and the ability to detect subtler differences between the groups. As a cross-sectional study, it also lacks the temporal resolution needed to assess the progression of vascular changes or establish causal relationships. Despite implementing Doppler ultrasonography with a standardized protocol, inter-observer and intra-observer variability were not formally evaluated. Furthermore, dialysis adequacy, type and dosage of phosphate binders, statin use, glycemic control, and markers of inflammation beyond CRP (such as IL-6 or TNF-α) were not assessed, all of which could contribute to vascular pathology. Moreover, the study was conducted at a single center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations with varying genetic, dietary, and clinical characteristics. Our biochemical assessment did not include advanced lipid parameters such as lipoprotein(a) or oxidized LDL, which have been shown to correlate with VC in ESRD. Also, Concomitant medications, including statins, were not collected and might have influenced lipid-related measurements. Moreover, vascular access type in HD patients was not recorded, which may affect inflammatory status and VC. Future research should prioritize multicenter longitudinal studies incorporating comprehensive vascular imaging (e.g., CT-based calcium scoring), biochemical profiling, and detailed pharmacological data to better delineate the contributors to vascular disease in dialysis patients. Exploring the role of non-traditional risk factors and the impact of novel interventions like magnesium supplementation or anti-calcification agents could also be valuable.