1. Background

After the creation of the ABO classification of blood groups in the twentieth century, the transfer of blood products has become one of the most important medical measures to save the lives of patients (1). The primary purpose of transfusing blood products is the treatment of chronic anemia, coagulation disorders, and fatal bleeding. However, there are other objectives, such as the treatment of von Willebrand disease, hemophilia A, factor XIII deficiency, and fibrinogen deficiency (2). Fibrinogen can also be used in surgeries such as organ transplants, cardiovascular surgeries, large tumor resections, and pregnancy-related complications (3).

Blood transfusion complications range from mild to life-threatening in terms of severity and are divided into acute and delayed types based on the time of occurrence: The acute type occurs during the transfusion or within the first 24 hours thereafter, and the delayed type occurs days or weeks after receiving the blood products (4). Acute transfusion reactions (ATRs) occur in 0.5% to 3% of transfusions globally. The incidence rates of ATRs include hemolytic reactions (1:30,000 to 1:76,000; 1:1.8 million fatal rate), febrile non-hemolytic reactions (FNHR) (0.1% to 1%), allergic reactions (1% to 2%), anaphylaxis (1:20,000 to 1:50,000; fatality rate 0.6 to 1.6 per 100,000 packed cell transfusions), septic reactions (platelet 1:25,000, packed cell 1:2.5), transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) (0.04% to 0.1%; mortality rate 5% to 15% despite supportive care), and transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) (1% up to 6% in critically ill patients). Delayed complications include alloimmunization of platelets and erythrocytes, delayed hemolytic complications, post-transfusion purpura, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), transfusion-transmitted infections (TTIs), and iron overload (1-5).

The ATRs are a significant concern in blood transfusion safety, with varying incidences reported globally. Packed red cells, anaphylactic reactions, TRALI, and sepsis related to transfusion may cause a notable proportion of moderate to severe reactions (6). Transfusion-related errors were reported in a substantial number of cases occurring during blood sample collection and handling, and misidentification of the patient at the time of injection, leading to adverse reactions and blood product wastage (7, 8). These findings emphasize the necessity of robust hemovigilance systems to enhance transfusion safety and prevent adverse events.

2. Objectives

The present study was conducted to determine the prevalence of ATRs and the relation of these reactions with demographic factors, previous blood transfusion history, and underlying diseases in a teaching hospital in southwestern Iran over a period of two years.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional study, conducted after receiving ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Dezful University of Medical Sciences (IR.DUMS.REC.1401.096), recorded information on blood-transfused patients with ATRs from Ganjavian Hospital, a teaching hospital in southwestern Iran (2020 - 2021). Data were manually extracted by trained staff. Underlying diseases were categorized according to clinician diagnosis. Inclusion criteria encompassed patients who experienced ATRs, while exclusion criteria involved ATR cases with incomplete records. Data collection involved manual review of medical records, utilizing standardized forms for data extraction. Variables collected included demographic characteristics (age, gender), type of blood product consumed, history of underlying diseases, and transfusion history. Underlying diseases were categorized based on clinical diagnosis.

3.1. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software version 8.3. Descriptive statistics included frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. The chi-square test was employed to compare patients with or without transfusion reactions, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

4. Results

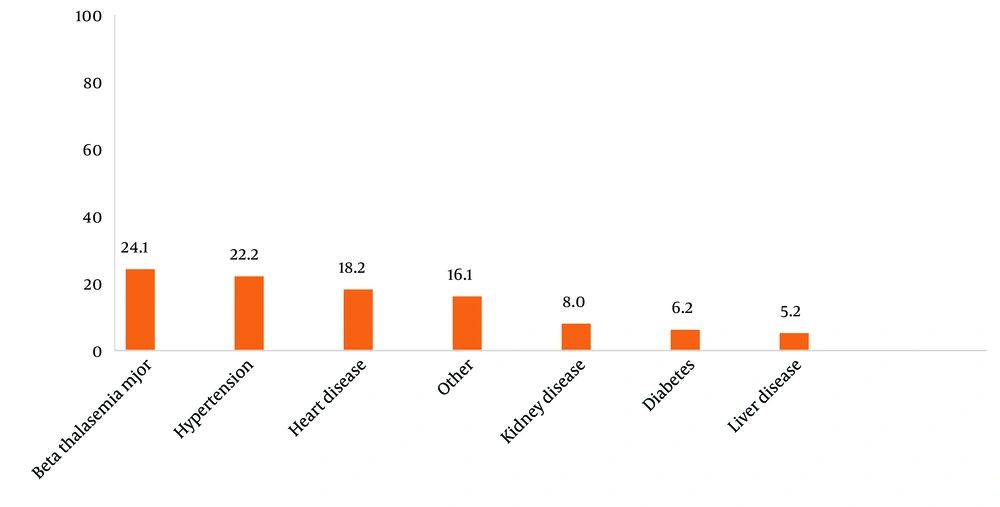

Among 36,959 transfusions, 100 patients experienced ATRs (57% men and 43% women). The youngest and oldest patients were 9 days and 89 years old, respectively, with an average age of 43.1 ± 20.86 years. Among patients with ATRs, 23% showed no history of disease, while 77% had a history of underlying diseases. The highest frequencies were related to patients with thalassemia major (24.1%), high blood pressure (22.2%), and heart diseases (18.2%), followed by other diseases (16.1%), kidney disease (8.0%), diabetes (6.2%), and liver disease (5.2%) (Figure 1). Among the blood products, packed RBCs had the highest consumption share, and the highest number of acute reactions was also related to this product. Cryoprecipitate and washed red blood cells had the lowest consumption and the lowest incidence of ATRs (Table 1). The findings showed that 48% of patients had no history of blood transfusion, 39% had a transfusion in less than three months, and 13% of patients had a history of transfusion more than three months ago. Patients with a history of blood transfusion had a higher frequency of ATRs compared to patients without a history of blood transfusion (52% vs. 48%). Statistical analysis also showed no significant difference between the group with and without a history of blood transfusion (P = 0.7).

Disease frequencies in all transfused patients. Among the transfused patients beta thalassemia major has the most rate. Other diseases included celiac disease, esophageal cancer, premature infant, pneumonia, ichthyosis, gastrointestinal bleeding, colon cancer, esophageal varices, intestinal obstruction, ovarian cancer, anemia, diabetic foot ulcer (each 1%). This graph shows the most recipients had no history of disease and then were major thalassemia.

| Products | Number (Units) | Frequency/Percentage | Number of Acute Reactions | Frequency Percentage of Acute Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood products consumed in 2020 | ||||

| Packed red blood cells | 6209 | 35.54 | 16 | 0.25 |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 2689 | 15.39 | 1 | 0.037 |

| Platelets | 4604 | 26.35 | 1 | 0.0217 |

| Cryoprecipitate | 668 | 3.82 | 0 | 0 |

| Leukoreduced red blood cells | 3062 | 17.52 | 1 | 0.032 |

| Washed red blood cells | 238 | 1.36 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 17470 | 99.98 | 19 | 0.34 |

| Blood products consumed at in 2021 | ||||

| Packed red blood cells | 7165 | 37.46 | 53 | 0.73 |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 1942 | 10.15 | 2 | 0.1 |

| Platelets | 5676 | 29.67 | 6 | 0.1 |

| Cryoprecipitate | 1138 | 5.95 | 2 | 0.17 |

| Leukoreduced red blood cells | 2905 | 15.19 | 18 | 0.61 |

| Washed red blood cells | 299 | 1.56 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 19125 | 99.98 | 81 | 0.42 |

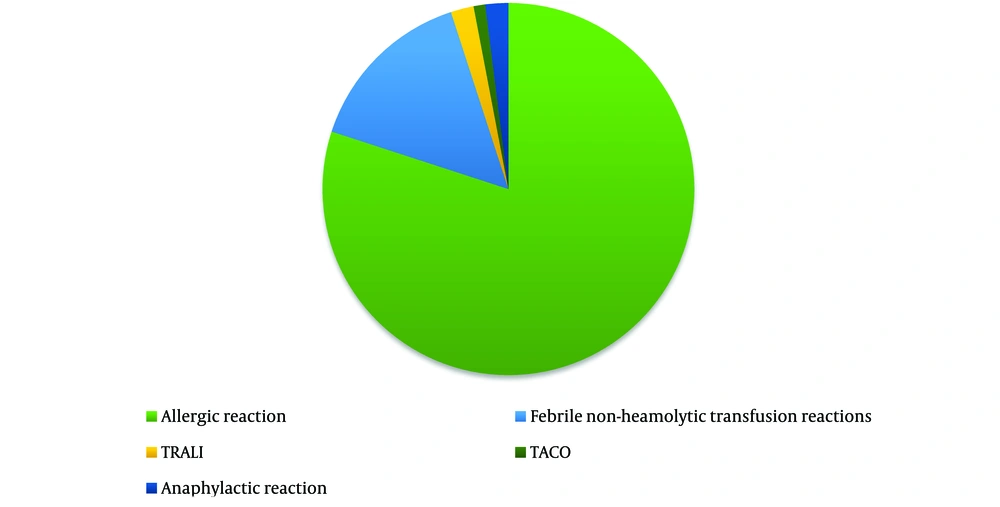

According to the findings, allergic reactions were the most common ATRs observed among blood and blood product recipients (80%) (Figure 2).

5. Discussion

Our findings confirm that allergic reactions and FNHRs are the most prevalent ATRs. The lack of significant relationships among underlying diseases suggests that other factors may contribute to triggering ATRs. For instance, allergic reactions may be influenced by genetic predispositions, plasma protein susceptibility, and the presence of IgE in recipients against these proteins. FNHRs are usually attributed to cytokines released from donor leukocytes during storage of blood components or recipient antibodies reacting against human leukocyte antigens (HLA) on donor leukocytes, especially in patients with a history of previous transfusion or pregnancy, or contamination of blood products with bacteria or certain medications in the recipient’s system (1-4).

In this study, a total of 36,959 transfused units resulted in 100 ATR cases. The age range of transfused patients was 9 days to 89 years. The most consumed blood product was packed cells, and the most common diseases among them were thalassemia major (24.1%) and hypertension (22.2%). Although the presence of anemia was significant in the two groups with and without acute transfusion complications (P = 0.006), no significant relationship was reported between other recorded underlying diseases (hypertension, diabetes, thyroid disorder, heart disease, kidney failure, malignancy, and liver disorder) in the two groups with and without acute complications (P < 0.05). No association between transfusion history and ATRs was observed (P = 0.7).

In a study by Azizi et al. at the Heart Center in Sari, out of a total of 9,193 blood products transferred, the product with the highest consumption was packed cells (69.4%). However, no definitive relationship between the type of product and the reactions was reported in their study (9). According to the results of our study, allergic reactions (80%) were the most common acute reactions due to blood transfusion, followed by FNHRs (15%), TRALI (2%), anaphylactic reactions (2%), and TACO (1%).

In the study by Bodaghkhan et al. conducted at Namazi Hospital in Shiraz, out of 57,902 blood recipients, 52 patients (0.1%) experienced acute transfusion complications, with FNHRs (48%) being the most common acute reaction, and allergic reactions ranking second (15%) (10). The study by Payandeh et al. showed that the most common acute reaction was allergic reactions (49.2%), which were accompanied by various skin manifestations such as itching, rash, and pruritus. An increase in body temperature 1°C above baseline was considered an FNHR, which was the second most common reaction (11).

In another study by Salimi et al. conducted at the Urmia Blood Transfusion Center, out of 261 cases of ATRs, the most common reactions were allergic reactions, FNHRs, and acute hemolytic reactions, respectively (12). This study aligns with our findings. A study in a tertiary care hospital in Bangladesh showed that transfusion reactions occurred in 11.5% of the 96 patients who received blood and blood products, with FNHRs (72.7%), allergic reactions (18.2%), and acute hemolytic transfusion reactions (9.1%) being the most common reactions, respectively (13).

According to reports at Methodist Hospital, Wenchi-Ghana, from January 2021 to December 2022, a total of 5,857 units of blood were used during the study period, with an incidence of 0.5 ATRs per 30 units of blood transfused. Factors such as previous history of transfusion, abortion, and longer storage of transfused blood were associated with an increased likelihood of ATRs. The number of transfused blood units also influenced the odds of developing ATRs (14). Contrary to the Wenchi-Ghana study, in our study, prior transfusions did not elevate the risk of ATRs (P = 0.7).

The study by Subair et al. monitored ATRs in pediatric patients, observing 329 ATRs out of 9,501 transfusions, supporting the incidence rate that showed the majority of reactions occurred within the first 2 hours of transfusion, with fever being the most frequently recorded symptom (61.5%) (15). Healthcare providers should be trained to recognize early signs of ATRs and implement strategies to mitigate risks.

5.1. Conclusions

This study showed a high prevalence of allergic and FNHR in blood transfusions. By recording and not neglecting blood reactions that occur immediately or within 24 hours of transfusion, and then analyzing the collected data by the hemovigilance department, errors can be identified and reduced to enhance patient safety and optimize transfusion protocols in future transfusions.

5.2. Study Limitation

This study has certain limitations, including its retrospective design and single-center data.