1. Background

The rise of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria poses a serious and growing threat to global health, undermining the efficacy of current treatments and endangering future generations. In response, the discovery of novel antimicrobial compounds has become an urgent priority. Natural products derived from bacteria remain one of the most promising sources of new antibiotics due to their structural diversity and potent bioactivity. However, the industrial-scale discovery of novel antibiotics has declined in recent decades, prompting researchers to explore unconventional biological niches for new microbial candidates. One such niche is the insect digestive tract, which harbors unique and underexplored microbial communities with antimicrobial potential (1).

The insect gut is a dynamic environment populated by both symbiotic and transient microorganisms that contribute to host health, nutrition, and defense. Insects such as aphids, cockroaches, termites, and wood-eating beetles have demonstrated beneficial relationships with their gut microbiota (2, 3). Similarly, honeybees (Apis spp.) possess a specialized gut environment enriched with nectar and pollen — nutrient-rich substances containing sugars, fatty acids, sterols, amino acids, essential vitamins, and rare minerals — that support the growth of metabolically diverse microbes (4). Among the commonly studied honeybee gut symbionts are Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which have been reported to produce bacteriocins and other antimicrobial peptides. However, these genera are primarily associated with probiotic functions and nutrient processing (5).

In contrast, rare genera such as Xenorhabdus — though less frequently isolated from honeybee guts — are known for their exceptional ability to produce structurally diverse and biologically active secondary metabolites. Xenorhabdus species are symbionts of entomopathogenic nematodes and have evolved to secrete antimicrobial, antifungal, and cytotoxic compounds to protect both themselves and their nematode hosts in hostile environments. This metabolic versatility makes Xenorhabdus a particularly attractive genus for antibiotic discovery (6). Notably, Xenorhabdus species are known producers of indole and indole-derived compounds, which exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Indole disrupts bacterial quorum sensing, inhibits biofilm formation, and interferes with cell membrane integrity, making it an effective agent against both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens, including resistant strains (6, 7).

Additionally, historical and modern studies have highlighted the antimicrobial properties of honey and honeybee-associated microorganisms. Honey has long been used in traditional medicine for treating infections, healing wounds, and soothing sore throats (8, 9). As antibiotic resistance escalates, exploring bacterial products derived from honeybees may lead to the identification of novel compounds for therapeutic use (1, 10). To date, at least twelve natural compounds from both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria have been developed into approved treatments for infectious diseases in humans and animals (11).

We hypothesized that Xenorhabdus strains isolated from the gut of wild honeybees produce novel antimicrobial compounds that are effective against drug-resistant human pathogens.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate the digestive tract of wild worker honeybees (Apis florea Fabricius, 1787) to isolate, identify, and characterize bacteria capable of producing antimicrobial agents.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling of Honeybee Gut

This study was conducted between 2023 and 2024 at Dezful University of Medical Sciences (Dezful, Khuzestan province, Iran). Adult healthy worker honeybees (A. florea Fabricius, 1787) were collected from eight distinct locations across Dezful city (32°02′44″N, 48°51′24″E), located in southwestern Iran near the Persian Gulf. At each location, 15 - 20 bees were collected, totaling approximately 130 individuals. To minimize seasonal variation in microbial composition, all collections were performed during the spring season under consistent weather conditions. The bees were placed in ventilated plastic containers (50 × 50 cm) and maintained with sugar cake until transported to the microbiology laboratory (12, 13).

3.2. Purification of Bacterial Colonies

The collected honeybees were externally sterilized using 70% ethanol, and their digestive tracts were homogenized in 0.9% saline solution for 3 minutes, followed by five washes with sterile water. Next, 1 mL of the gut homogenate was inoculated into tubes containing tryptic soy broth (TSB) and incubated on an orbital shaker at 150 rpm and 28°C for 48 hours. To isolate single colonies, 0.1 mL of the bacterial suspension was spread onto tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates and incubated at 28°C for 48 hours. Different pure colonies were selected based on color and morphology for further studies. These isolates were preserved in 1.5 mL microtubes containing 30% glycerol-TSB and stored at -80°C (12, 13).

3.3. Cell Morphology and Biochemical Tests

The isolates were examined for colony size, pigment production, cell shape, and arrangement using Gram staining and optical microscopy. Biochemical characterization was performed through tests such as citrate fermentation, sulfide indole motility, urease, oxidase, catalase, DNase, and hydrogen sulfide production (14).

3.4. Antibiotic Sensitivity

The disk diffusion method was employed to assess the antibiotic susceptibility of the isolates to penicillin (10 μg), clindamycin (5 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), and erythromycin (15 μg). Each isolate was spread over the surface of Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates, followed by the placement of antibiotic disks. Plates were incubated at 28°C for 24 hours, and the diameter of clear inhibition zones was measured in millimeters using a standard ruler.

3.5. Antimicrobial Potential

The study targeted serious human pathogenic bacteria, including Bacillus cereus ATCC 11778, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 10231, Escherichia coli O157 PTCC 1276, Streptococcus mutans ATCC 35668, Klebsiella pneumoniae PTCC 10031, Shigella flexneri PTCC 1234, Staphylococcus aureus ATTC25923, and Candida albicans ATCC 10231. The isolates were inoculated into 50 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing TSB medium and incubated at 28°C with shaking for 7 days. The bacterial supernatants were separated from the broth by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 20 minutes, then filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter (15).

3.6. Minimum Inhibitory and Bactericidal Concentration

A single colony of the selected isolate was inoculated in a 1000 mL flask containing 500 mL TSB, then incubated at 28°C with shaking at 150 rpm for 7 days. For bacterial extraction, 1000 mL of ethyl acetate was added to the broth culture and perfectly mixed, then allowed to stand at room temperature for 24 hours. The bacterial extract was concentrated via a rotary vacuum evaporator. The bacterial extraction was conducted three times to enhance the concentration of crude compounds, and was dried under laminar airflow, then stored at -20°C for further studies (16). The MIC of the extracted supernatant against pathogenic bacteria was measured using the microbroth dilution technique based on the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS). The MIC Index is defined as the minimum concentration that entirely prevented bacterial growth after 48 hours of incubation at 30°C. Different concentrations of the supernatant (101 g/mL to 1010 g/mL) were prepared to determine the MIC value against the tested pathogenic bacteria. Fifty μL of MHB medium and 50 μL of the 0.5 McFarland suspension of pathogenic bacteria were added into the wells. Finally, different concentrations of the antibacterial extract (25 μL) were inoculated into the same wells. The positive control wells contained 0.5 McFarland (OD: 600) of the pathogens and culture medium, while the negative control wells were filled with an antimicrobial extract and culture media. The 96-well microplates were placed in an incubator for 24 hours at 30°C. After that, the MIC value was defined as the first well in which the visible growth of pathogens was inhibited. The MBC was determined by spreading 20 μL of non-growing well contents onto agar plates and observing the absence of bacterial growth after incubation at 30°C for 24 hours (15).

3.7. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

The GC/MS analysis was conducted to identify unknown antibacterial compounds in the bacterial extract using a Hewlett-Packard HP-5890 Series II gas chromatograph equipped with a split/splitless injector and a capillary column (30 m, 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm) fused with phenylpolysilphenylene siloxane. The temperatures for the injector and detector were configured at 280°C and 300°C, respectively. The oven temperature was initially set at 80°C for 1 minute and then increased to 300°C at a rate of 20°C/min. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. A 2 μL volume of the sample was injected in splitless mode, with a purge time of 1 minute. The mass spectrometer (Hewlett-Packard 5889B MS Engine) operated at 70 eV, scanning fragments from 50 to 650 m/z. Peak identification was performed by comparing the obtained mass spectra with the NIST library (17).

3.8. Statistical Analysis

All assays were performed in triplicate. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and all analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 16.

4. Results

4.1. Isolation of Antimicrobial-Producing Bacteria

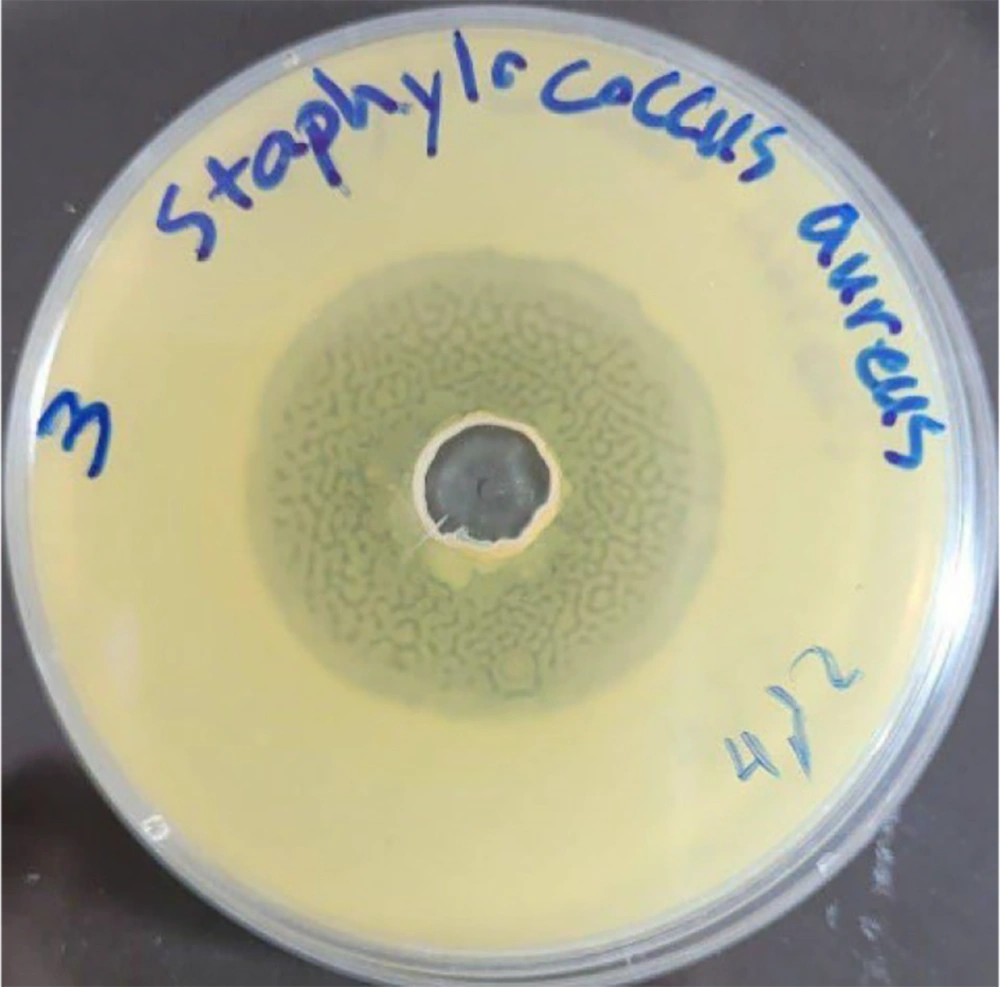

In this study, nine different colonies were isolated from the gut content of wild honeybees. They were purified using TSA medium and preserved in a refrigerator at -80°C. These bacterial colonies were studied for their antibacterial abilities using the agar diffusion method. Among them, isolate Kamangar, 2024 showed obvious potential for suppressing the tested pathogens. The filtered bacterial supernatant of isolate Kamangar, 2024 inhibited the indicator pathogenic microorganisms, including S. aureus, S. mutans, E. coli, Enterococcus faecalis, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and C. albicans to varying degrees. The highest antibacterial activity was recorded at 29 ± 1.2 mm against S. aureus (Figure 1).

The strain Kamangar, 2024 showed the best broad-spectrum antibacterial potential, that was selected for further studies (Table 1).

| Microorganism | Inhibition Zone (mm) | MIC (mg/mL) | MBC (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 29 ± 1.2 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

| Streptococcus mutans | 10 ± 0.8 | 0.047 | 0.047 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 8 ± 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 11 ± 0.6 | 0.047 | 0.047 |

| Shigella flexneri | 19 ± 0.9 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

| Escherichia coli | 16 ± 1.0 | 0.047 | 0.047 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 12 ± 0.7 | 0.023 | 0.023 |

| Candida albicans | 18 ± 0.9 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

Abbreviations: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; MBC, minimum bactericidal concentration.

4.2. The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration Values

The MIC and MBC values demonstrate that the extract of Xenorhabdus khoisanae strain Kamangar, 2024 displays significant antimicrobial activity against pathogenic microorganisms. Table 1 shows the MIC and MBC of X. khoisanae strain Kamangar, 2024 against these microorganisms. The most pronounced antimicrobial effect is observed against S. aureus, with a 29 ± 1.2 mm inhibition zone and an MIC of 0.011 mg/mL.

4.3. Physiological and Biochemical Characteristics

The strains were initially identified through colony size, type of pigment, and microscopic shape. The summary of their biochemical characteristics is presented in Table 2. Based on Gram staining and the snot test, the isolate was identified as a gram-negative rod bacterium. For phenotypical characterization, the antibiotic resistance of isolated strains towards different antibiotics was also determined (Figure 1B). Strain Kamangar, 2024 was found to be sensitive to penicillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, and ceftriaxone disks.

| Strains | Gram | Oxidase | Shape | Colony Color | Oxidase | Catalase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | - | - | Coccobacillus | Yellowish cream | - | + |

| B | - | - | Coccus | Yellowish cream | - | + |

| C | - | - | Coccobacillus | Green | - | + |

| C1 | - | - | Bacillus | Shiny cream | - | + |

| C2 | - | - | Coccobacillus | Matte cream | - | + |

| C3 | - | - | Coccobacillus | Shiny cream | - | + |

| C4 | - | - | Coccobacillus | Shiny cream | - | + |

| C5 | - | - | Coccobacillus | Pale green | - | + |

| C6 | - | - | Bacillus | Matte cream | - | + |

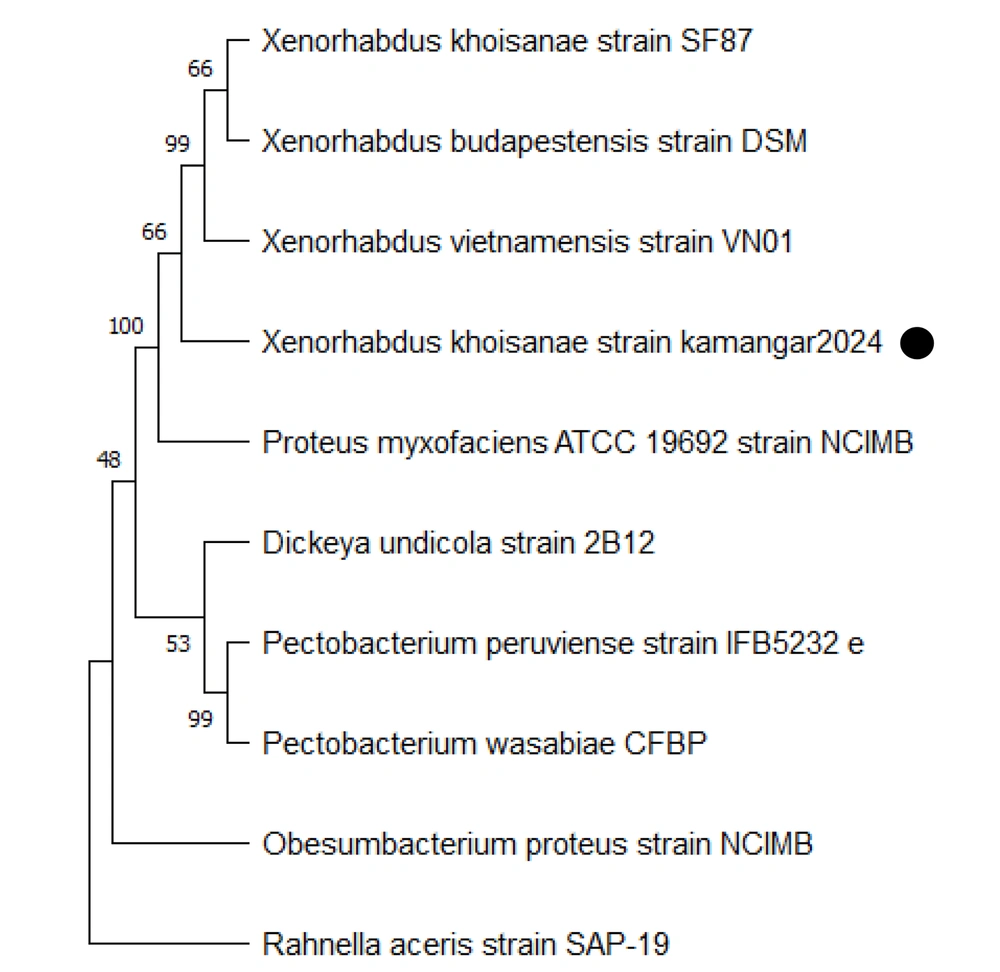

4.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

The phylogenetic tree of X. khoisanae strain Kamangar, 2024 was constructed using the 16S rDNA gene sequence and comparing sequence homology with the GenBank database. The analysis of genetic evolutionary relationships showed that strain Kamangar, 2024 had high similarity with X. khoisanae, sharing 99%. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of the mentioned strain was submitted to GenBank with accession number PQ283207. Additionally, the phylogenetic tree of 16S rRNA gene sequences of the isolates is presented in Figure 2.

4.5. Chemical Composition of Bacterial Extract

The gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was used to analyze the bacterial supernatant and its components. Based on the analysis of GC-MS data, the compounds along with their percentages, formulas, retention times, and molecular weights can be found in Table 3. According to the present results for X. khoisanae strain Kamangar, 2024, two compounds were identified in greater concentration relative to other detected compounds, such as cyclopentane, methyl, and decane.

| No | Compound Name | Percentage | Retention Times | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cyclopentane, methyl | 22.74 | 6.351 | C6H12 |

| 2 | Nonane, 3-methyl- | 0.46 | 13.853 min | C10H22 |

| 3 | Cyclopentane, 1-hexyl-3-methyl- | 0.45 | 14.356 | C12H24 |

| 4 | Decane | 3.83 | 14.728 | C10H22 |

| 5 | Nonanal | 0.50 | 17.246 | C9H18O |

| 6 | Undecane, 5-methyl- | 0.11 | 19.420 | C12H26 |

| 7 | Decane, 3,8-dimethyl- | 0.08 | 19.861 | C12H26 |

| 8 | Cyclododecane | 0.11 | 20.364 | C12H24 |

| 9 | Dodecane | 1.20 | 20.708 | C12H26 |

| 10 | Nonanoic acid | 0.04 | 22.012 | C9H18O2 |

| 11 | Indole | 0.05 | 22.361 | C8H7N |

| 12 | 2,4-Decadienal, (E,E | 0.17 | 23.277 | C10H16O |

| 13 | Pyridine, 3-(1-methyl-2-pyrrolid | 0.11 | 24.290 | C10H14N2 |

| 14 | Tetradecane | 0.39 | 26.161 | C14H30 |

| 15 | Cyclododecane | 0.16 | 27.620 | C12H24 |

| 16 | Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | 0.09 | 28.455 | C17H30OSi |

| 17 | Cycloheptasiloxane, tetradecamet... | 0.08 | 29.056 | C14H42O7Si7 |

| 18 | Hexadecane | 0.21 | 31.042 | C16H34 |

| 19 | 2-Tetradecene, (E)- | 0.09 | 32.507 | C14H28 |

| 20 | Octadecane | 0.09 | 36.054 | C18H38 |

| 21 | Phthalic acid, isobutyl nonyl ester | 0.07 | 36.724 | C21H32O4 |

| 22 | 7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5 | 0.04 | 37.788 | C17H30O |

| 23 | Eicosane | 0.05 | 38.143 | C20H42 |

| 24 | Eicosane | 0.04 | 39.722 | C20H42 |

| 25 | Eicosane | 0.07 | 42.737 | C20H42 |

5. Discussion

5.1. The Gut Microbiota of Honeybees

The gut microbiota of honeybees plays a critical role in protecting the host against pathogens by producing antimicrobial molecules and compounds. This study investigated bacteria with antimicrobial activity in the honeybee gut. Among nine isolates, the C1 bacterial strain exhibited significant antimicrobial effects against tested pathogens. Strains isolated during the winter were identified as Xenorhabdus species. Of these isolates, only one strain showed strong antimicrobial activity, while others demonstrated moderate or weak effects. The GC-MS analysis revealed that indole was the dominant antimicrobial compound produced by this strain, although it was present at a relatively low concentration (0.05%). Despite its low abundance, the observed strong antimicrobial effect suggests that indole may act synergistically with other detected compounds, such as nonanal and phenol derivatives, which also have documented antimicrobial properties. These synergies could enhance the overall efficacy of the bacterial extract and warrant further investigation.

Our findings are in line with those of Khaled et al., who reported the isolation of antimicrobial-producing bacteria, primarily Brevibacillus laterosporus, from the honeybee gut (18). Similarly, various Xenorhabdus species — including X. khoisanae, X. szentirmaii, and X. stockiae — have been reported to produce diverse antimicrobial compounds such as PAX lipopeptides, xenopeptides, and indole derivatives (19-21). Importantly, although X. khoisanae strain Kamangar, 2024 was sensitive to penicillin, it demonstrated inhibitory effects against MRSA. This apparent paradox may be explained by the unique mechanism of action of indole derivatives. Unlike β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin, which target bacterial cell wall synthesis, indole and its derivatives interfere with bacterial transcription machinery. Structural studies, such as those by Sundar, showed that indole derivatives inhibit RNA polymerase activity by increasing intracellular ppGpp levels, leading to suppression of RNA synthesis and growth arrest in actively dividing cells (6, 22). Therefore, indole may bypass conventional β-lactam resistance mechanisms and retain activity against resistant strains like MRSA.

Furthermore, the chemical diversity of Xenorhabdus spp. suggests that indole might not be the sole contributor to antimicrobial activity. Previous studies report the production of multiple classes of bioactive compounds, including xenocoumacins, xenortides, and others alongside indole (23). This highlights the possibility that the C1 strain’s antimicrobial potency arises from a complex mixture of synergistic metabolites. Given these promising results, further studies are warranted to (A) isolate and structurally characterize all bioactive compounds present in the extract; (B) synthesize and test indole derivatives for improved antimicrobial activity, and (C) perform in vivo toxicity and efficacy assays to assess their therapeutic potential. Understanding these interactions will provide insights into novel antimicrobial development strategies using gut-derived microbiota.

5.2. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that X. khoisanae strain Kamangar, 2024, isolated from the honeybee digestive tract, produces indole, a compound capable of effectively inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant strains. These findings highlight the potential of this strain as a source for developing novel natural antibiotics. Further biochemical and molecular studies of this bacterium will provide valuable insights for future research in biological and medical fields. The application of this microorganism could play a crucial role in addressing the challenges posed by antibiotic resistance, paving the way for innovative treatments.