1. Background

Intensive care units (ICUs) house patients with poor health who often have at least one life-threatening condition (1). An intensive care unit (ICU) provides specialized equipment and medical and nursing care, resulting in high healthcare expenditure within this unit (2, 3). Allocating resources according to the needs of patients in the ICU is essential for the quality of care (4). The prediction of mortality in the ICU has been a critical issue in medicine for decades, as it is used to prioritize patients and make critical decisions (5, 6). Most researchers predict mortality using severity of illness scoring systems designed for risk estimation 24 hours after ICU admission or data-mining algorithms (7). The three major predictive scoring systems used to predict mortality in general ICU patients are the Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) scoring system, the Simplified Acute Physiologic Score (SAPS), and the Mortality Prediction Model (MPM0) (8). A study comparing traditional scoring models for mortality prediction showed that the performance of the APACHE II/III scoring systems was higher than that of other systems (9). Overall, previous studies have indicated that the accuracy of machine learning models is higher than traditional scoring models, and clinicians should select models that have been more validated (10). Several studies have shown that ensemble models like Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting for mortality prediction are more accurate (11, 12). The novel proposed algorithm is based on the generalization stacking ensemble model (also called the stacking ensemble model) and has presented a heterogeneous ensemble classifier for ICU mortality prediction (13). A machine learning model was developed to predict patients admitted to the ICU for acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding with a 2% - 10% mortality risk (14). A developed predictive model to predict patients with sepsis in the ICU can help physicians make optimal clinical decisions, thereby reducing the mortality rate (15). Some previous studies have demonstrated that deep-learning models can identify novel temporal data patterns predictive of ICU mortality and achieve higher accuracy in identifying patients at high risk of death (16, 17). Therefore, predicting mortality in the ICU is very important, and using machine learning models is associated with better performance.

2. Objectives

The present study aims to use ensemble models to reduce the prediction error of mortality in the ICU. We intend to compare the performance of bagging and boosting methods and predict the mortality of patients admitted to the ICU using demographic, clinical, and laboratory information.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Design

From February 2020, the demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of 2,055 adult patients admitted to the ICU in one of the selected hospitals were recorded for one year (Table 1). Data were initially entered into a paper form and then into the spreadsheet of SPSS software. This study was conducted by the Critical Care Quality Improvement Research Center, Shahid Modarres Hospital. The present study was approved by medical science review boards (IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1402.350).

| Features | Outcomes | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expired (n = 865) | Discharged (n = 1190) | ||

| Age (y) | 61.6 ± 14.3 | 50.1 ± 14.7 | < 0.001 b |

| Receiving AB (d) | 8.6 ± 6.1 | 7.3 ± 4.5 | < 0.001 b |

| Before ICU (d) | 3.3 ± 3.1 | 1.6 ± 2.5 | < 0.001 b |

| T (min) | 36.9 ± 0.3 | 36.9 ± 0.3 | 0.96 |

| T (max) | 38.7 ± 0.7 | 38.6 ± 0.6 | 0.11 |

| BP (min) | 99.3 ± 18.5 | 92.4 ± 19.2 | < 0.001 b |

| BP (max) | 126.7 ± 21.4 | 118.6 ± 21.8 | < 0.001 b |

| PR (min) | 73.6 ± 14.0 | 72.4 ± 14.0 | 0.054 |

| PR (max) | 102.3 ± 12.4 | 101.6 ± 12.6 | 0.18 |

| RR (min) | 19.0 ± 5.3 | 19.6 ± 5.4 | 0.019 b |

| RR (max) | 28.3 ± 6.4 | 28.8 ± 6.5 | 0.079 |

| pH | 7.3 ± 0.1 | 7.3 ± 0.1 | 0.071 |

| PaO2 | 69.1 ± 22.7 | 69.2 ± 22.8 | 0.94 |

| PaCO2 | 39.8 ± 11.3 | 39.8 ± 11.4 | 0.935 |

| Na (min) | 129.4 ± 3.0 | 129.6 ± 2.9 | 0.293 |

| Na (max) | 138.8 ± 3.8 | 139.4 ± 3.3 | 0.001 b |

| BG (min) | 120.9 ± 45.5 | 93.4 ± 21.4 | < 0.001 b |

| BG (max) | 214.1 ± 86.0 | 161.6 ± 49.7 | < 0.001 b |

| Cr (min) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | < 0.001 b |

| Cr (max) | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 b |

| BUN (min) | 31.0 ± 9.7 | 27.1 ± 8.4 | < 0.001 b |

| BUN (max) | 55.9 ± 28.3 | 47.7 ± 15.8 | < 0.001 b |

| UA (vol) | 2181.8 ± 740.7 | 2366.8 ± 577.8 | < 0.001 b |

| Alb | 3.3 ± 0.54 | 3.3 ± 0.55 | 0.88 |

| Bili | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 1.4 | 0.067 |

| Hct (min) | 32.0 ± 4.8 | 30.3 ± 5.1 | < 0.001 b |

| Hct (max) | 40.8 ± 4.8 | 39.3 ± 5.0 | < 0.001 b |

| WBC | 9120.1 ± 3319.5 | 8735.6 ± 3008.4 | 0.007 b |

| GCS | 10.7 ± 2.5 | 10.7 ± 2.4 | 0.965 |

| FiO2 | 45.6 ± 19.5 | 47.7 ± 20.6 | 0.017 b |

| Gender | 0.842 | ||

| Female | 416 | 567 | |

| Male | 449 | 623 | |

| Nosocomial | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 201 | 106 | |

| Negative | 664 | 1084 | |

| Surgery | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 340 | 794 | |

| Negative | 526 | 396 | |

| Emergency surgery | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 191 | 432 | |

| Negative | 674 | 758 | |

| Diabetes | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 446 | 185 | |

| Negative | 419 | 1005 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 108 | 33 | |

| Negative | 757 | 1157 | |

| Liver failure | 0.012 b | ||

| Positive | 12 | 37 | |

| Negative | 853 | 1153 | |

| Intubation | 0.06 | ||

| Positive | 355 | 538 | |

| Negative | 510 | 652 | |

| HIV | 0.316 | ||

| Positive | 1 | 4 | |

| Negative | 864 | 1186 | |

| Lymphoma | 0.429 | ||

| Positive | 14 | 25 | |

| Negative | 851 | 1165 | |

| Metastasis | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 59 | 143 | |

| Negative | 806 | 1047 | |

| Leukemia | 0.036 b | ||

| Positive | 0 | 6 | |

| Negative | 865 | 1184 | |

| Immunosuppression | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 175 | 120 | |

| Negative | 690 | 1070 | |

| Readmission | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 329 | 222 | |

| Negative | 536 | 968 | |

| Myocardial infarction | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 292 | 99 | |

| Negative | 573 | 1091 | |

| Central venous catheter line | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 601 | 545 | |

| Negative | 264 | 645 | |

| Tracheostomy | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 154 | 37 | |

| Negative | 711 | 1153 | |

| Nasogastric tube | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 856 | 1053 | |

| Negative | 9 | 137 | |

| Packed cell | 0.288 | ||

| Positive | 216 | 322 | |

| Negative | 649 | 868 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 221 | 61 | |

| Negative | 644 | 1129 | |

| Anesthetic | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 754 | 872 | |

| Negative | 111 | 318 | |

| Total parenteral nutrition | < 0.001 b | ||

| Positive | 221 | 43 | |

| Negative | 644 | 1147 | |

| Alcohol | 0.113 | ||

| Positive | 41 | 40 | |

| Negative | 824 | 1150 | |

| Site | < 0.001 b | ||

| Blood | 16 | 4 | |

| Wound | 9 | 7 | |

| Urine | 65 | 40 | |

| Sputum | 111 | 55 | |

| Not infected | 664 | 1084 | |

| Pathogen | < 0.001 b | ||

| Candidia | 6 | 0 | |

| Escherichia coli | 39 | 32 | |

| Acinetobacter | 44 | 30 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 47 | 17 | |

| Pseudomonas | 13 | 4 | |

| Klebsiella | 52 | 23 | |

| Not infected | 664 | 1084 | |

| Ward | < 0.001 b | ||

| Surgery | 142 | 409 | |

| Internal | 328 | 123 | |

| Emergency | 395 | 658 | |

| The main AB used | < 0.001 b | ||

| AB1 | - | - | |

| AB2 | - | - | |

| Reason for admission | < 0.001 b | ||

| Others | 238 | 299 | |

| Respiratory | 287 | 99 | |

| Other surgeries | 140 | 296 | |

| Trauma surgery | 92 | 337 | |

| Brain surgery | 108 | 159 | |

Abbreviations: AB, antibiotics; ICU, intensive care unit; T, temperature; BP, blood pressure; PR (min), minimum pulse rate; PR (max), maximum pulse rate; RR (min), minimum respiration rate; RR (max), maximum respiration rate; Na (min), minimum blood sodium; Na (max), maximum blood sodium; BG, blood glucose; Cr, blood creatinine; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; UA (vol), urine volume; Alb, albumin; Bili, bilirubin; Hct (min), minimum blood hematocrit level; Hct (max), maximum blood hematocrit level; WBC, white blood cell count; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; FiO2, percentage of inspiratory oxygen; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a Values are expressed as No. or mean ± SD.

b Statistically significant.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

The data collected from 2,055 patients had no missing or duplicate values. The target variable in this problem has two values: Class 0 refers to discharged, and class 1 refers to expired. Due to the removal of outliers, the frequency of the target variable changed, necessitating the use of oversampling. Class imbalance is a serious problem for classification problems. The SMOTE algorithm can generate random sample points, improving the imbalance rate (18). We utilized the interquartile range (IQR) to identify and remove outliers and excluded rows with missing values. The data were separated into training and testing sets by 80% and 20%, respectively. We used a label encoder for binary columns and one-hot encoding for columns with more than two values.

3.3. Models

The ensemble learning structure is a combination of two or more classifiers instead of an individual classifier, aiming to increase prediction accuracy. In addition to being highly accurate, we aim to reduce biases or high variance, as one of the problems of individual classifier learners is that they can be high bias, highly variant, or both (19). The popular ensemble techniques are bagging, boosting, and stacking (20):

- Bagging involves fitting many decision trees on different samples of the same dataset and averaging the predictions.

- Boosting involves adding ensemble members sequentially that correct the predictions made by prior models and output a weighted average of the projections.

- Stacking involves fitting many different model types on the same data and using another model to learn how to best combine the predictions.

A RF algorithm is a supervised machine learning algorithm that is extremely popular and is used for classification and regression problems in machine learning. It is a classifier that contains several decision trees on various subsets of the given dataset and takes the average to improve the predictive accuracy of that dataset, which refers to the bagging definition. A previous study has shown that the RF classifier has a higher classification rate than single classifiers and takes less training time than decision tree and support vector machine (21). Light GBM (LGBM) is a high-performance gradient-boosting framework that uses a tree-based learning algorithm. The LGBM splits the tree leaf-wise with the best fit, whereas other boosting algorithms like XGBoost (XG) separate the tree depth-wise or level-wise rather than leaf-wise. In other words, LGBM grows trees vertically, while different algorithms grow trees horizontally. Previous studies have concluded that LGBM can significantly outperform XG in terms of computational speed, memory consumption, and accuracy (22, 23). To develop the models, we employed the default parameter settings of the RF, XG, and LGBM libraries, ensuring a standard approach to model training and evaluation.

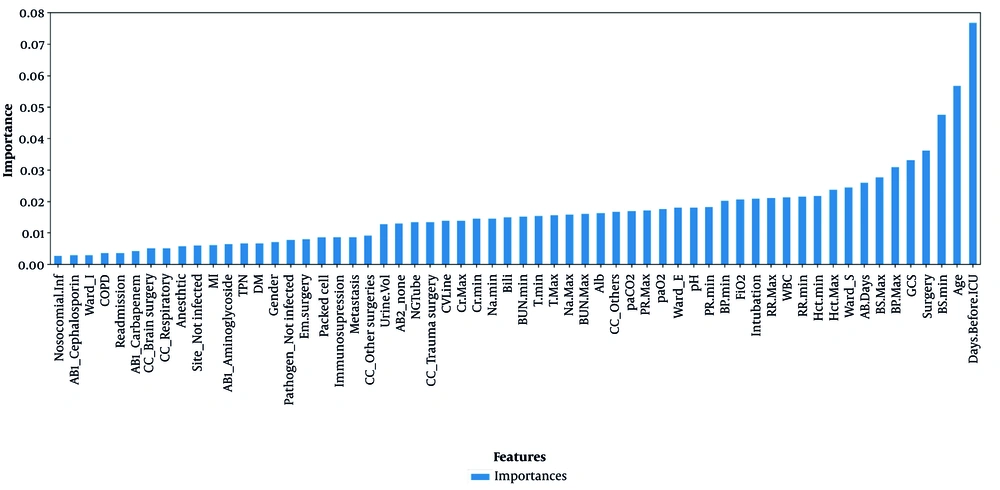

3.4. Feature Selection and Modeling

Feature selection is a necessary stage of data analysis for selecting a small set of relevant features. The RF classifier is an instrumental base for the wrapper algorithms solving all relevant problems because it provides the variable importance measure (24). We used RF feature selection to avoid overfitting the model (Figure 1). Based on expert opinion, we removed the features whose importance was less than 0.00237 and then proceeded to build the models. Additionally, we used the logistic regression model to report the individual ratio measure with a confidence level of 95%, making its interpretation suitable for doctors.

3.5. Software

In this study, we used SPSS version 22 software for statistical analysis and machine learning models implemented by Python libraries of Scikit-learn, XG, and LGBM. Regarding the hardware, our CPU was an Intel i5 2.53 GHz with 8 GB installed memory.

4. Results

4.1. Participants

In the data of 2,055 patients, 983 cases were women, and 1,072 cases were men, with a mean (SD) age of 55.93 (15.7) and 54.14 (15.4), respectively. In general, 865 patients died, and 1,190 were discharged. The results of Figure 1 show that the number of days of hospitalization before entering the ICU has the most substantial impact on the construction of the models. Table 1 shows that the difference between the two groups (expired and discharged) is significant, with the quartile difference between the first and third patients who died being five days, with a mean of 3.3 (3.1); for the discharge group, it is two days, with a mean of 1.6 (2.5). Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients in the ICU in two groups: Death and survival. Statistical tests were performed for each of the factors, which include: Age, number of days receiving antibiotics (AB), blood pressure (BP), minimum respiration rate [RR (min)], maximum blood sodium [Na (max)], blood sugar (BG), blood creatinine (Cr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), urine volume [UA (vol)], blood hematocrit level (Hct), white blood cell count (WBC), percentage of inspiratory oxygen (FiO2), hospital infection, surgery, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, liver failure, metastasis, immunodeficiency, readmission, heart attack, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, leukemia, tracheostomy, and reason for ICU admission. These tests separately show that there is a significant difference.

4.2. Models Validation

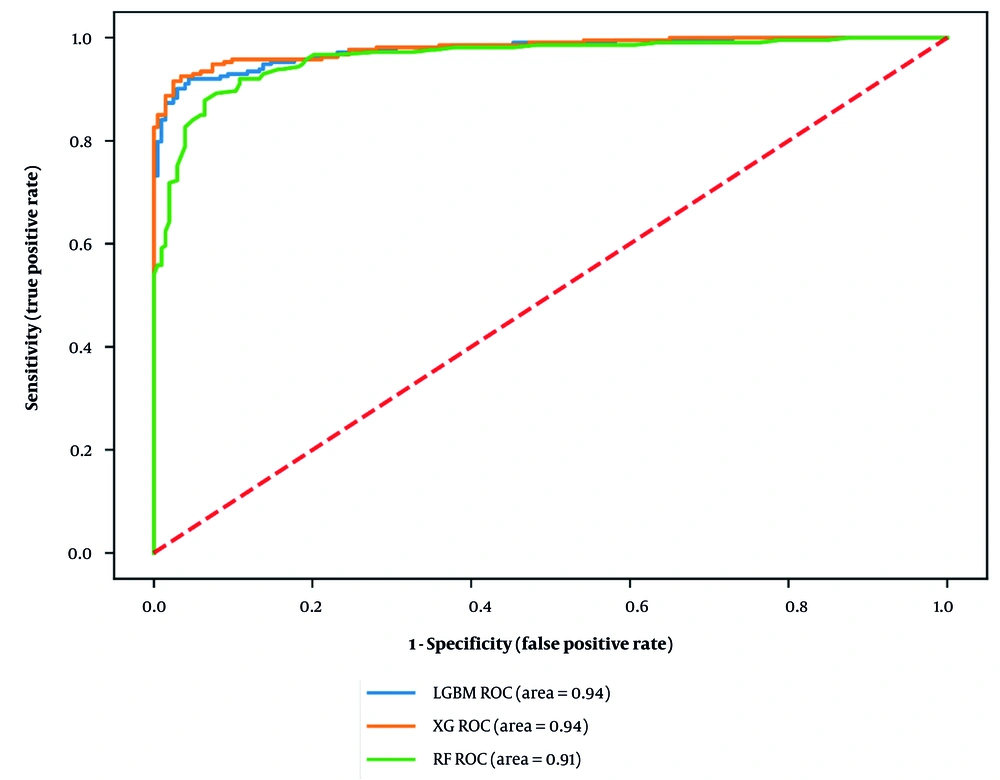

We developed three mortality ensemble models: Model 1: Light GBM, model 2: XGBoost, and model 3: Random forest. After adjusting the hyperparameters, we considered 100 estimators for RF and 150 estimators for LGBM and XG. The research indicated that the accuracy of the RF model is 0.91, while LGBM and XG both achieved an accuracy of 0.93. Other evaluation criteria are reported in Table 2. We also compared them using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, with RF (area = 0.91), LGBM (area = 0.94), and XG (area = 0.94), leading to the conclusion that LGBM and XG had almost the same performance (Figure 2).

| Models | Accuracy | F-Score | Recall | Precision | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGBM | 0.937 | 0.937 | 0.919 | 0.955 | 0.956 |

| XG | 0.937 | 0.936 | 0.923 | 0.950 | 0.951 |

| RF | 0.911 | 0.912 | 0.880 | 0.945 | 0.944 |

Abbreviations: LGBM, LightGBM; XG, XGBoost; RF, Random Forest.

5. Discussion

Based on past studies conducted in the field of mortality in the ICU and the differences between ensemble models and individual models, this study aimed to compare the performance of ensemble models, particularly the bagging and boosting methods, to improve the prediction of mortality in the ICU. The study demonstrated that the performance of boosting methods is superior to bagging. One of the attractions of using ensemble models is the stacking method, as different results can be obtained by combining different classifiers. This method can be used for future studies and offers innovation. In this study, in addition to highlighting the importance of each patient’s characteristics in mortality, we used logistic regression to report the odds ratio criterion with a confidence level of 95%. The odds ratio is a statistical measure of the association between binary variables across two different groups, where one group is referred to as the independent group, while the other is the dependent group (25). This criterion is widely used in the medical community and is suitable for the interpretation of predictors (Table 3).

| Predictors | P-Value (0.05) | Odd Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | 0.000 | 0.963 | 0.951 | 0.975 |

| Brain surgery | 0.304 | 1.355 | 0.759 | 2.421 |

| Trauma surgery | 0.046 | 1.870 | 1.012 | 3.456 |

| Other surgeries | 0.842 | 1.041 | 0.704 | 1.537 |

| Respiratory | 0.000 | 0.394 | 0.264 | 0.590 |

| AB (d) | 0.000 | 1.101 | 1.064 | 1.140 |

| GCS | 0.001 | 1.185 | 1.073 | 1.308 |

| Nosocomial infection | 0.030 | 1.537 | 1.044 | 2.264 |

| Emergency surgery | 0.001 | 2.501 | 1.467 | 4.263 |

| Diabetes | 0.000 | 5.492 | 3.506 | 8.604 |

| Intubation | 0.008 | 0.414 | 0.215 | 0.796 |

| Metastasis | 0.000 | 0.224 | 0.128 | 0.394 |

| Immunosuppression | 0.000 | 2.916 | 1.915 | 4.441 |

| MI | 0.010 | 1.679 | 1.130 | 2.494 |

| CVLine | 0.000 | 1.671 | 1.256 | 2.224 |

| Tracheostomy | 0.000 | 9.987 | 5.406 | 18.450 |

| COPD | 0.000 | 4.159 | 2.760 | 6.268 |

| Anesthetic | 0.000 | 4.124 | 2.909 | 5.847 |

| TPN | 0.000 | 4.357 | 2.660 | 7.139 |

| Gender (male) | 0.872 | 1.027 | 0.744 | 1.417 |

| BP (max) | 0.016 | 0.987 | 0.976 | 0.997 |

| Before ICU (d) | 0.000 | 0.879 | 0.837 | 0.923 |

| FiO2 | 0.368 | 1.005 | 0.994 | 1.018 |

| Bili | 0.001 | 1.194 | 1.074 | 1.328 |

| Readmission | 0.007 | 1.615 | 1.142 | 2.284 |

| Hct (max) | 0.047 | 0.950 | 0.903 | 0.999 |

| T (min) | 0.306 | 1.236 | 0.824 | 1.853 |

| Alb | 0.272 | 0.878 | 0.696 | 1.108 |

| BUN (min) | 0.016 | 0.974 | 0.954 | 0.995 |

| BG (min) | 0.768 | 1.001 | 0.995 | 1.007 |

| Na (min) | 0.465 | 0.984 | 0.943 | 1.027 |

| Na (max) | 0.292 | 0.980 | 0.944 | 1.017 |

| PR (min) | 0.172 | 0.994 | 0.985 | 1.003 |

| Cr (min) | 0.154 | 1.950 | 0.779 | 4.880 |

Abbreviations: AB, antibiotics; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; BP, blood pressure; ICU, intensive care unit; FiO2, percentage of inspiratory oxygen; Bili, bilirubin; Hct (max), maximum blood hematocrit level; T, temperature; Alb, albumin; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; BG, blood glucose; Na (min), minimum blood sodium; Na (max), maximum blood sodium; PR (min), minimum pulse rate; Cr, blood creatinine.

This study identified which characteristics of patients in the ICU have a significant relationship with mortality. Patients whose reason for referral was trauma surgery had a lower mortality risk, whereas patients with respiratory problems were at higher risk of mortality. Factors such as age, high blood pressure, blood urea nitrogen, the number of days receiving antibiotics, readmission to the ICU, and the number of days of hospital stay before entering the ICU were directly related to increased mortality risk. This study also showed that although intubated patients were less prone to mortality, they were more inclined to mortality under tracheostomy. Among other factors influencing the death rate in the ICU is nosocomial infection, which has a direct relationship with mortality. The GCS criterion has an inverse relationship with mortality; these relationships are clinically acceptable. Our sample size was only sufficient to find statistically significant large associations. The purpose of developing predictive models in machine learning is to aid in decision-making, and the more accurate the model’s performance, the more reliable it is. This study sought to improve the prediction performance of mortality in the ICU by using ensemble models.

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the accuracy of traditional scoring methods in past studies, we found that machine learning methods have higher accuracy. In this study, the performance of ensemble models was reported to be better than individual models used in previous studies. Furthermore, when comparing ensemble methods (bagging and boosting), boosting techniques (LGBM, XG) demonstrated similar performance and were superior to the bagging strategy (RF).