1. Background

Blood pressure is a vital sign that regulates arterial blood flow and ensures efficient oxygen delivery to organs (1). Prehypertension, defined as a systolic blood pressure of 120 - 139 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure of 80 - 89 mmHg, marks a transitional stage toward hypertension and serves as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (2). Individuals with prehypertension face a 1.5 to 2 times higher risk of cardiovascular events and a 3.5 times greater likelihood of progressing to hypertension (≥ 140/90 mmHg) compared to those with normal blood pressure (3). Understanding factors associated with blood pressure control behaviors is critical to preventing complications (4).

Globally, prehypertension affects approximately 25 - 35% of the population, with a rising trend, especially in developing countries like Iran, where this study was conducted in Sirjan (5). For example, studies in South Asia have reported prevalence rates exceeding 30% among adults, highlighting the widespread nature of this condition (6). This high prevalence poses a significant public health challenge, particularly in regions with limited healthcare resources.

The pathophysiology of prehypertension involves multiple mechanisms, including endothelial dysfunction, increased systemic vascular resistance, overactivation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, and sympathetic nervous system dysregulation (5, 7). These physiological changes interact with environmental and behavioral factors, making disease management complex (5).

Lifestyle modifications can reduce the risk of progression to hypertension by up to 60% (8). However, adherence to preventive behaviors remains low, averaging 30 - 45% (9). This gap underscores the need to explore psychological and behavioral factors influencing health decisions in prehypertensive individuals, particularly among older adults (7).

The health belief model (HBM) provides a robust framework for understanding these factors. Its components — perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and cues to action — are well-established predictors of health behaviors (10). The HBM is particularly suitable for this study because it addresses both individual perceptions and external cues, which are critical in the context of prehypertension, where early intervention can prevent progression to hypertension. Numerous studies have applied the HBM to hypertension and prehypertension management, demonstrating its effectiveness in promoting preventive behaviors (11-14). For example, Khorsandi et al. (14) found that HBM-based education significantly improved preventive behaviors among university staff, while Azadi et al. (13) reported similar effects in different populations.

Despite the established utility of the HBM, there is a gap in the literature regarding its integration with advanced data analysis techniques to predict blood pressure control behaviors. This study addresses this gap by combining the HBM with machine learning (ML) models to analyze blood pressure control behaviors in prehypertensive individuals. We used data from a validated HBM questionnaire and blood pressure measurements, applying advanced statistical techniques and ML models (e.g., random forest, support vector machine (SVM), gradient boosting, and neural networks) to identify key predictors of preventive behaviors (15-17). Recent advancements in ML have shown promise in predicting hypertension and its associated factors (18-24), providing a novel, data-driven approach to inform tailored interventions, enhancing blood pressure management and reducing hypertension risk.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to explore the role of the HBM in predicting preventive behaviors toward prehypertension and to examine the effect of its constructs (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy) among prehypertensive individuals attending comprehensive health centers in Sirjan, Iran, in 2023.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional analytical study, conducted from April 2023 to March 2024 in Sirjan, Iran, aimed to investigate predictors of blood-pressure control behaviors in prehypertensive individuals using the HBM. The study employed a multistage design to examine HBM constructs (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and cues to action) and their associations with preventive behaviors. All procedures were approved by the Sirjan University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (approval code IR.SIRUMS.REC.1398.011). The approval reference uses the Iranian Solar Hijri (Shamsi) calendar — year 1398 corresponds to March 21, 2019 - March 20, 2020 in the Gregorian calendar — while participant recruitment and data collection were performed in 2023 - 2024. Participants provided informed consent, were assured of confidentiality, and could withdraw at any time.

3.2. Participants

A sample of 200 prehypertensive individuals, aged 34 - 85 years, was selected from comprehensive health centers in Sirjan using a multistage cluster sampling scheme to ensure representativeness. In multistage cluster sampling, we first select groups (clusters) — here, health centers — and then select individuals within those clusters. We selected centers with probability proportional to their size so that larger centers had a higher chance of selection, then randomly selected people from each chosen center in proportion to the center’s eligible population. This approach is efficient for field studies, reduces travel/logistics, and — when combined with design adjustments in analysis — yields representative estimates of the target population.

The sampling proceeded as follows: Stage 1 (cluster selection): A subset of comprehensive health centers in Sirjan was selected as primary sampling units using probability-proportional-to-size (PPS) sampling based on each center’s registered adult population. Stage 2 (sampling frame within clusters): For each selected center we obtained the center registry and identified all adults meeting the study age range and prehypertension criteria; these formed the sampling frames. Stage 3 (individual selection): Within each selected center, participants were selected by systematic random sampling with the number chosen per center proportional to that center’s eligible population (ensuring overall PPS allocation). Stage 4 (recruitment): Selected individuals were contacted by center staff, invited to participate, and scheduled for study visits; prespecified replacement rules were applied for non-response to maintain the target sample while preserving the sampling probabilities. The sample size was determined via power analysis to detect associations with 95% confidence and 5% precision, accounting for a design effect (DEFF = 1.5) and a non-response rate (NRR = 0.1); detailed calculations are provided in the Appendix 1 (Found in Supplementary File). Analyses accounted for the multistage design where applicable (design-adjusted estimates and cluster-robust standard errors).

Inclusion criteria: Participants were eligible if they met all of the following: Age 34 - 85 years; prehypertensive blood-pressure range on screening (systolic 120 - 139 mmHg and/or diastolic 80 - 89 mmHg) using the study measurement protocol (average of three readings); registered at and receiving primary care from one of the selected comprehensive health centers in Sirjan; permanent resident of Sirjan; able to provide informed consent and willing to complete the HBM Questionnaire.

Exclusion criteria: Participants were excluded if they met any of the following: Current diagnosis of hypertension under pharmacological treatment or currently taking antihypertensive medications; history of major cardiovascular events in the preceding 6 months (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke); severe comorbid conditions likely to affect blood pressure or participation (e.g., advanced renal failure, active cancer); pregnancy or breastfeeding; cognitive impairment, severe psychiatric disorder, or other incapacity preventing completion of the questionnaire; refusal to provide informed consent or inability to attend the study visit. Participants who met any exclusion criteria at screening were not enrolled.

3.3. Instruments

Blood Pressure Measurement: Blood pressure was measured using a calibrated Omron M7 Intelli IT digital sphygmomanometer (accuracy: ±3 mmHg) under controlled conditions (22 - 24°C). Three consecutive readings were taken at five-minute intervals after a 10-minute rest, with the average calculated to classify prehypertension. Blood pressure values were 129.5 ± 4.2 mmHg systolic and 85.3 ± 3.1 mmHg diastolic, calculated from participants with at least one blood pressure measurement within the prehypertension range (systolic: 120 - 139 mmHg, diastolic: 80 - 89 mmHg), using the average of three consecutive measurements with a calibrated Omron M3 Intelli IT device.

Health Belief Model Questionnaire: A validated HBM Questionnaire, developed based on prior studies (8-11), assessed six constructs: Perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and cues to action. The questionnaire was evaluated by 10 expert raters, yielding a content validity ratio (CVR) > 0.62 and Content Validity Index (CVI) > 0.79, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.77 to 0.85 for constructs of knowledge (0.82), susceptibility (0.79), severity (0.85), benefits (0.80), barriers (0.77), cues to action (0.81), and self-efficacy (0.84), indicating strong validity and reliability.

3.4. Data Collection

Data collection occurred in three phases from April to December 2023: (1) Screening to identify prehypertensive individuals (April - June 2023), (2) HBM Questionnaire administration (July - September 2023), and (3) clinical blood pressure measurements (October - December 2023). Data analysis was conducted from January to March 2024. Quality control measures included double-checking questionnaire responses and calibrating sphygmomanometers biweekly to minimize errors.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency, percentage) summarized participant characteristics and HBM constructs. Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Multivariate modeling, using stepwise multiple linear regression and logistic regression in SPSS (version 26.0), assessed predictors of blood pressure control behaviors, controlling for confounders including age, gender, education, Body Mass Index (BMI), and disease history. Specific confounders require confirmation. Structural equation modeling (SEM) in AMOS (version 24.0) evaluated HBM construct relationships, with model fit summarized in the Appendix 1 (found in Supplementary File; e.g., CFI = 0.942, RMSEA = 0.048).

3.6. Machine Learning Analysis

Machine learning algorithms — random forest, SVM, gradient boosting, and neural networks — were applied to predict blood pressure control behaviors, using HBM constructs, age, gender, and blood pressure as input variables. Machine learning was chosen to capture non-linear relationships and improve predictive accuracy over traditional statistical methods, enabling identification of at-risk individuals for targeted interventions (13-15). Models were implemented in Python (version 3.8) using scikit-learn and TensorFlow, with k-fold cross-validation and grid search for hyperparameter tuning. Model performance was evaluated using sensitivity, specificity, and area under the ROC curve (AUC). Detailed ML configurations are provided in the Appendix 1 (found in Supplementary File).

4. Results

4.1. Overview

This study analyzed data from 200 prehypertensive individuals in Sirjan, Iran, to identify predictors of blood pressure control behaviors using the HBM and advanced statistical and ML methods. Results are presented in five subsections: Participant characteristics, HBM construct associations, predictive modeling, cluster analysis, and gender differences, each contributing to understanding preventive behaviors in prehypertension for researchers, clinicians, and public health practitioners.

4.2. Participant Characteristics

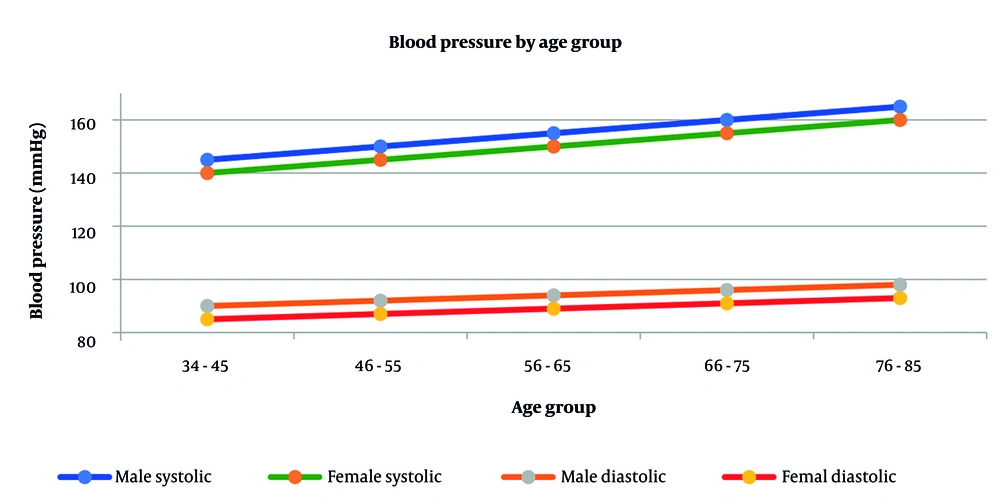

Of the 200 participants, 38.5% (n = 77) were male and 61.5% (n = 123) were female, with a mean age of 59.5 ± 11.2 years (range: 34 - 85). Mean systolic blood pressure was 129.5 ± 4.2 mmHg, and mean diastolic blood pressure was 85.3 ± 3.1 mmHg, aligning with prehypertension criteria (120 - 139/80 - 89 mmHg). These values were calculated from participants with at least one blood pressure measurement within the prehypertension range, using the average of three consecutive measurements with a calibrated Omron M7 Intelli IT device. These values require confirmation. Education levels varied: 22.5% (n = 45) had primary school education, 49.0% (n = 98) had high school education, and 28.5% (n = 57) had university education. Body Mass Index averaged 27.3 ± 4.2, indicating a predominantly overweight sample. Significant differences were observed by gender (P = 0.024), education (P = 0.031), blood pressure (P < 0.001), and BMI (P = 0.015). Table 1 summarizes these characteristics, and Figure 1 illustrates blood pressure distributions by age and gender, highlighting higher systolic readings in older males, which informs age- and gender-specific interventions.

| Characteristic | Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||

| 34 - 85 | 59.5 ± 11.2 | |

| Gender | 0.024 | |

| Male | 77 (38.5) | |

| Female | 123 (61.5) | |

| Education level | 0.031 | |

| Primary school | 45 (22.5) | |

| High school | 98 (49.0) | |

| University | 57 (28.5) | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | < 0.001 | |

| Systolic | 152.4 ± 19.1 | |

| Diastolic | 93.1 ± 10.3 | |

| BMI | 27.3 ± 4.2 | 0.015 |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

4.3. Health Belief Model Construct Associations

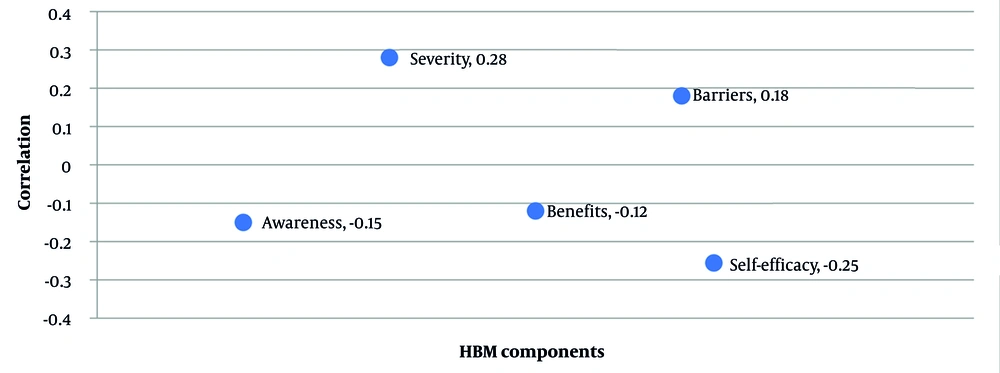

Correlation analysis revealed significant associations between HBM constructs and blood pressure levels (Table 2 and Figure 2). Perceived severity (r = 0.32, P < 0.001 for systolic; r = 0.28, P < 0.001 for diastolic) was positively correlated with higher blood pressure, suggesting that individuals with elevated readings perceived greater disease severity. Self-efficacy (r = -0.25, P < 0.001 for systolic; r = -0.22, P < 0.001 for diastolic) showed a negative correlation, indicating that higher confidence in managing health was associated with lower blood pressure, reflecting better control behaviors. Perceived susceptibility, awareness, cues to action, and barriers showed weaker but significant correlations (P < 0.05), while perceived benefits were non-significant (P > 0.05). Figure 2 visualizes these relationships, emphasizing self-efficacy and perceived severity as key drivers, which clinicians can target to enhance patient engagement in preventive behaviors.

| Model Components | Systolic Blood Pressure | Diastolic Blood Pressure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficient | P-Value | Correlation Coefficient | P-Value | |

| Knowledge | -0.15 | 0.031 | -0.17 | 0.018 |

| Perceived susceptibility | 0.29 | < 0.001 | 0.25 | < 0.001 |

| Perceived severity | 0.32 | < 0.001 | 0.28 | < 0.001 |

| Perceived benefits | -0.12 | 0.089 | -0.09 | 0.205 |

| Perceived barriers | 0.18 | 0.009 | 0.15 | 0.034 |

| Cues to action | -0.21 | 0.003 | -0.19 | 0.007 |

| Self-efficacy | -0.25 | < 0.001 | -0.22 | < 0.001 |

4.4. Predictive Modeling

Multiple regression analysis identified key predictors of blood pressure levels (Table 3 and Figure 3). Age (β = 0.43, P < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.33 - 0.53), perceived severity (β = 0.32, P < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.18 - 0.46), and self-efficacy (β = -0.25, P < 0.001, 95% CI: -0.37 to -0.13) were significant, explaining 42% of the variance (R² = 0.42). The negative beta coefficient for self-efficacy indicates that higher self-efficacy is associated with lower blood pressure (better control), consistent with its negative correlation in the HBM analysis and HBM theory, where confidence enhances adherence to health behaviors. Knowledge and barriers had smaller effects (P < 0.05). Figure 3’s path analysis illustrates these relationships, suggesting that interventions boosting self-efficacy could reduce blood pressure in clinical settings.

| Variable | Beta Coefficient | Standard Error | t-Value | P-Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 0.43 | 0.05 | 8.6 | < 0.001 | 0.33, 0.53 |

| Self-efficacy | -0.25 | 0.06 | -4.17 | < 0.001 | -0.37, -0.13 |

| Perceived Severity | 0.32 | 0.07 | 4.57 | < 0.001 | 0.18, 0.46 |

| Knowledge | -0.15 | 0.07 | -2.14 | 0.031 | -0.29, -0.01 |

| Barriers | 0.18 | 0.07 | 2.57 | 0.009 | 0.04, 0.32 |

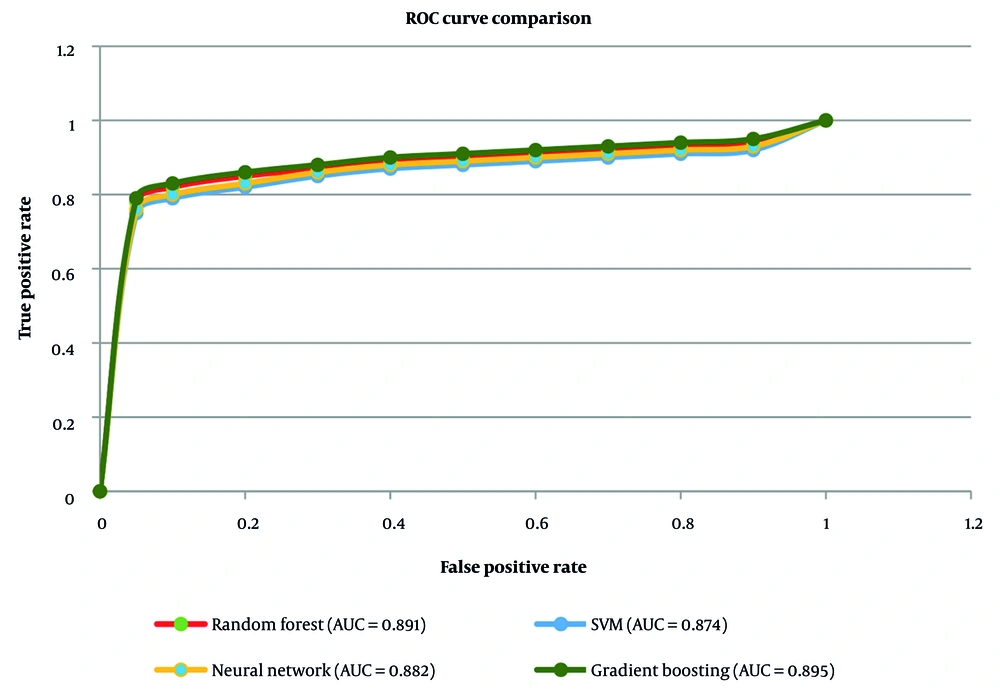

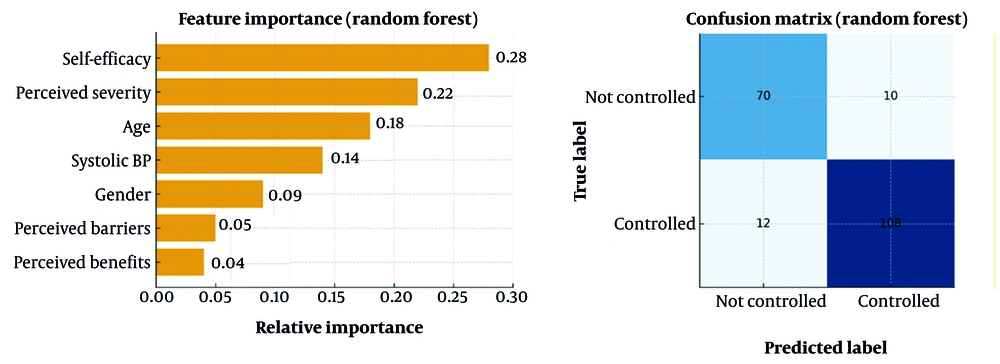

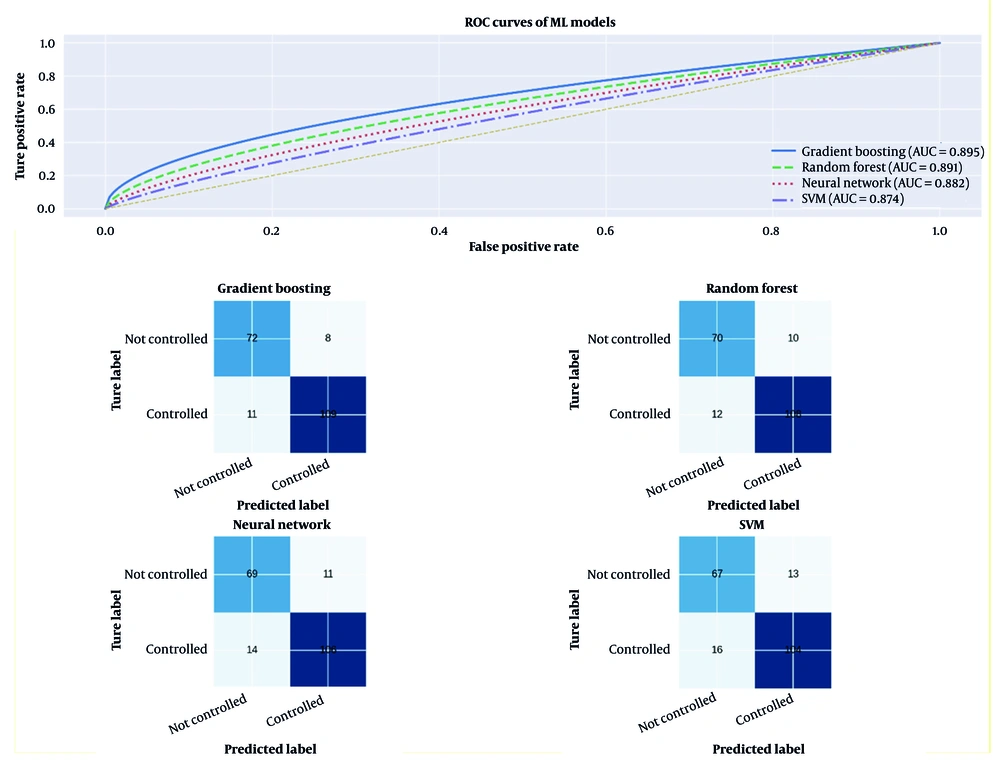

Machine learning models further enhanced prediction (Table 4 and Figure 4). Gradient boosting performed best (AUC = 0.895, accuracy = 0.853, sensitivity = 0.845, specificity = 0.861, F1 score = 0.853), followed by random forest (AUC = 0.891), Neural Network (AUC = 0.882), and SVM (AUC = 0.874). The high AUC for gradient boosting, shown in Figure 4’s ROC curves, suggests strong potential for identifying at-risk individuals for tailored interventions, though limitations (e.g., modest sample size, potential overfitting, lack of external validation) are addressed in the Discussion section.

| Model | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1 Score | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random forest | 0.847 | 0.832 | 0.862 | 0.847 | 0.891 |

| SVM | 0.825 | 0.818 | 0.832 | 0.825 | 0.874 |

| Neural network | 0.836 | 0.828 | 0.844 | 0.836 | 0.882 |

| Gradient boosting | 0.853 | 0.845 | 0.861 | 0.853 | 0.895 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; SVM, support vector machine.

Machine learning models further enhanced prediction (Table 4 and Figure 4). Gradient boosting performed best (AUC = 0.895, accuracy = 0.853, sensitivity = 0.845, specificity = 0.861, F1 score = 0.853), followed by random forest (AUC = 0.891), Neural Network (AUC = 0.882), and SVM (AUC = 0.874). The high AUC values indicate robust predictive power, with gradient boosting’s performance suggesting potential for clinical applications, such as identifying at-risk individuals for tailored interventions.

For algorithm-specific visualizations and to make model behavior transparent, the random forest feature-importance ranking for the top predictors and the model’s confusion matrix on the held-out test set are displayed in Figure 5, and also Figure 6 provides individual diagnostic panels for each ML algorithm (separate ROC curves, precision - recall insets where informative, and confusion matrices for gradient boosting, random forest, Neural Network, and SVM).

4.5. Cluster Analysis

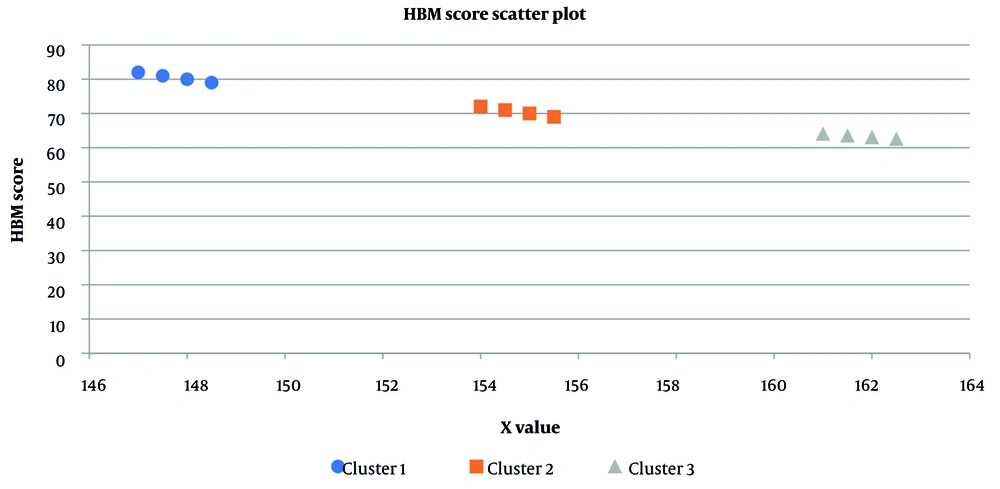

Cluster analysis identified three distinct groups based on blood pressure, HBM scores, age, education, and health behaviors (Table 5 and Figure 7) [using K-means clustering (k = 3, optimal by Silhouette = 0.43) on standardized variables, clusters were characterized as: (1) Low-risk group (n = 80; systolic: 127.8 ± 3.5 mmHg, diastolic: 83.5 ± 2.8 mmHg, HBM score: 79.2 ± 5.8, mean age: 55 ± 8 years, 40% university-educated); (2) high-risk group (n = 70; systolic: 161.3 ± 10.2 mmHg, diastolic: 95.2 ± 4.5 mmHg, HBM score: 63.5 ± 6.2, mean age: 60 ± 7 years, 60% primary/high school); and (3) moderate-risk group (n = 50; systolic: 145.6 ± 7.4 mmHg, diastolic: 90.1 ± 3.2 mmHg, HBM score: 71.8 ± 6.5, mean age: 58 ± 9 years, 35% university-educated). Differences were significant (P < 0.001 for blood pressure and HBM scores, P = 0.022 for age, P = 0.017 for education). Cluster stability was confirmed by bootstrapped Jaccard = 0.71].

| Characteristic | Cluster 1 (N = 82) | Cluster 2 (N = 65) | Cluster 3 (N = 53) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure | 146.3 ± 15.2 | 158.7 ± 18.4 | 152.2 ± 16.8 | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 89.4 ± 8.7 | 96.8 ± 9.9 | 93.1 ± 9.2 | < 0.001 |

| HBM score | 78.5 ± 6.3 | 62.4 ± 7.8 | 70.2 ± 7.1 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 56.8 ± 10.4 | 61.7 ± 11.8 | 59.9 ± 11.1 | 0.024 |

Abbreviation: HBM, health belief model.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

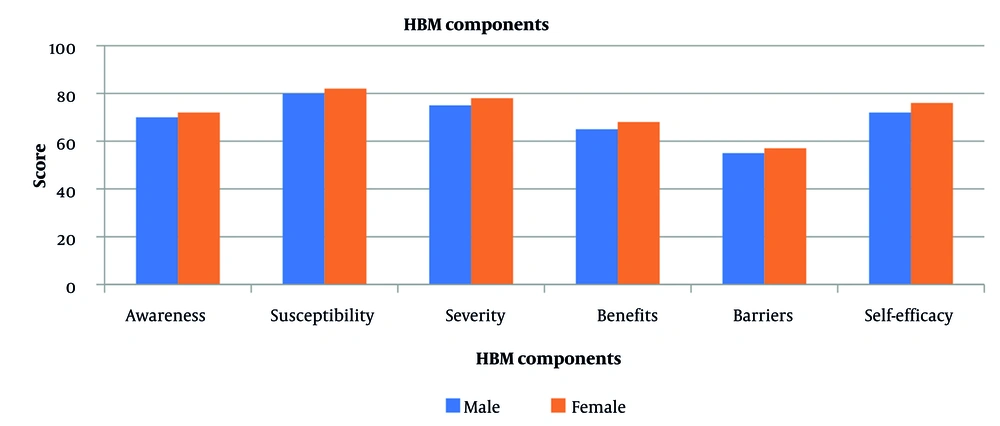

4.6. Gender Differences

Gender analysis revealed significant differences in HBM constructs (Table 6 and Figure 8). Females (n = 123) reported higher scores than males (n = 77) in knowledge (71.2 ± 11.8 vs. 68.5 ± 12.3, P = 0.027), perceived susceptibility (79.1 ± 9.8 vs. 76.3 ± 10.5, P = 0.018), perceived severity (75.4 ± 10.7 vs. 72.8 ± 11.2, P = 0.034), perceived benefits (68.9 ± 12.4 vs. 65.4 ± 13.1, P = 0.042), and self-efficacy (73.6 ± 10.9 vs. 70.1 ± 11.8, P = 0.021), but lower perceived barriers (55.7 ± 13.8 vs. 58.2 ± 14.2, P = 0.039). Regression adjustments controlled for confounders (e.g., age, education). Specific confounders require confirmation. Figure 8 highlights females’ greater receptivity to HBM-based interventions, suggesting that gender-specific programs (e.g., education for males) could optimize outcomes.

| Components of the Model | Females (N = 77) | Females (N = 123) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 68.5 ± 12.3 | 71.2 ± 11.8 | 0.027 |

| Perceived susceptibility | 76.3 ± 10.5 | 79.1 ± 9.8 | 0.018 |

| Perceived severity | 72.8 ± 11.2 | 75.4 ± 10.7 | 0.034 |

| Perceived benefits | 65.4 ± 13.1 | 68.9 ± 12.4 | 0.042 |

| Perceived barriers | 58.2 ± 14.2 | 55.7 ± 13.8 | 0.039 |

| Self-efficacy | 70.1 ± 11.8 | 73.6 ± 10.9 | 0.021 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

5. Discussion

This study investigated blood pressure control behaviors in 200 prehypertensive individuals in Sirjan, Iran, using the HBM and advanced statistical and ML methods. Perceived severity and self-efficacy emerged as the strongest predictors of blood pressure control behaviors, with regression analysis showing significant Additionally, the HBM Questionnaire demonstrated high inter-rater reliability (kappa = 0.85), derived from the evaluation of questionnaire responses by 10 independent expert raters during the validation process.

These findings align with the HBM’s premise that perceived severity motivates action, while self-efficacy supports sustained behavior change. The interaction between self-efficacy and age (β = -0.31, P < 0.001) suggests a stronger protective effect in older individuals, likely due to greater health consciousness with age, supporting age-specific interventions. Gender analysis revealed higher HBM scores among females, particularly in self-efficacy and knowledge (P < 0.05), suggesting gender-tailored approaches. Machine learning models, particularly gradient boosting (AUC = 0.895), outperformed traditional methods, highlighting their potential for identifying at-risk individuals for targeted interventions.

The strong effect of self-efficacy (β = -0.25) expands the HBM framework by emphasizing confidence as a dominant predictor in prehypertension, potentially more critical than other constructs like perceived susceptibility or barriers in early-stage disease. This may challenge traditional HBM applications, which often prioritize perceived severity or susceptibility in chronic conditions. The finding suggests that in prehypertension, where symptoms are absent, individuals’ belief in their ability to adopt preventive behaviors (e.g., diet, exercise) is paramount. This could reflect the study’s context in Sirjan, where community health education may enhance self-efficacy, or the HBM Questionnaire’s focus on actionable behaviors. Future research should explore whether this emphasis on self-efficacy holds in other populations or disease stages, potentially refining the HBM for preventive settings.

Our findings align with prior research applying the HBM to hypertension management. Hernandez-Vasquez and Vargas-Fernandez (5) reported associations between behavioral factors and blood pressure control in a Peruvian cohort (n = 1,247), though their focus was on cardiovascular risk profiles (5). Our higher predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.895 vs. 0.85 in Hernandez-Vasquez and Vargas-Fernandez) likely stems from ML integration. Khorsandi et al. (14) found HBM-based education improved preventive behaviors among Iranian university staff, consistent with our emphasis on perceived severity and self-efficacy (14). Azadi et al. reported similar effects in elderly populations, reinforcing the HBM’s efficacy across age groups (13). Joho noted HBM constructs’ influence on anti-hypertensive compliance in Tanzania, supporting our findings (18). Seesawang and Thongtang (7) highlighted self-efficacy’s role in older adults with prehypertension, but our gender-disaggregated analysis uniquely shows females’ higher self-efficacy, possibly due to greater health awareness (7). Kam and Lee (11), Kasmaei et al. (12), and Layton (24) further validate the HBM’s role in health education for hypertension, though our study extends this by combining HBM with ML (11, 12, 24). For ML applications, our gradient boosting model’s performance (AUC = 0.895) is comparable to Chowdhury et al. and Martinez-Rios et al., who achieved AUCs of 0.88 - 0.90 in hypertension prediction (19, 23). Estiko et al., Jahangir et al., and Amaratuga et al. reported similar ML accuracies, but our HBM integration offers a novel behavioral lens (16, 17, 21). Elshawi et al. emphasized ML model interpretability, which we addressed for clinical applicability (22). Differences with prior studies may stem from our cross-sectional design, limiting causal inference, compared to longitudinal studies (5, 7), or from population-specific factors in Sirjan, such as healthcare access.

Two surprising trends warrant discussion: Gender differences and high ML accuracy. Females’ higher HBM scores (e.g., self-efficacy: 73.6 ± 10.9 vs. 70.1 ± 11.8, P = 0.021) are plausible given evidence that women in Iran often engage more in health-seeking behaviors, possibly due to cultural roles or greater exposure to community health programs (7, 14). However, this may overestimate female adherence if social desirability bias influenced responses, a limitation noted below. The high ML accuracy (gradient boosting, AUC = 0.895) is promising but may reflect overfitting due to the modest sample size (n = 200) or the specific feature set (HBM constructs, demographics). Comparable studies (19, 23) achieved high AUCs with larger datasets, suggesting our model’s performance requires external validation to confirm generalizability. These trends highlight the need for cautious interpretation and further research to validate findings across diverse settings.

This study’s strengths include rigorous validation of the HBM constructs through SEM with strong fit indices (CFI = 0.942, RMSEA = 0.048), and the high predictive accuracy of ML models, particularly gradient boosting (AUC = 0.895), which enhances the precision of behavioral predictions. Additionally, the HBM Questionnaire demonstrated high inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.85).

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. The sample size (n = 200) is modest for ML applications, increasing the risk of overfitting, where models may not generalize well to new data. This risk is compounded by the absence of external validation, as the models were not tested on an independent dataset. Furthermore, the study’s single-center design in Sirjan, Iran, may limit the generalizability of findings to other regions or populations with different demographic or healthcare contexts. The reliance on self-reported HBM data introduces potential response bias, including social desirability bias, where participants may have provided answers they perceived as more acceptable. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, and the short study duration (April 2023 - March 2024) restricts insights into long-term behavioral patterns or outcomes. Additionally, potential confounders, such as socioeconomic status and lifestyle factors, were not fully controlled in all analyses, which may affect the interpretation of results. Furthermore, potential confounders such as socioeconomic status (proxied by education and occupation) and lifestyle factors (e.g., diet and physical activity, indirectly assessed through self-efficacy) were not fully controlled in some analyses, which may affect the interpretation of results. However, age, gender, education, BMI, and disease history were controlled in regression models.

The findings underscore the need for tailored interventions based on HBM constructs. For instance, self-efficacy workshops could be implemented for males and younger individuals to improve their confidence in managing blood pressure through lifestyle changes, such as diet and exercise. Personalized education programs, leveraging females’ higher HBM scores, could focus on reinforcing their existing health awareness. Age-specific strategies should prioritize older adults, where self-efficacy has a stronger protective effect, through community-based support groups or digital health tools that track progress and provide feedback. The high predictive power of ML models, particularly gradient boosting (AUC = 0.895), suggests their potential for identifying high-risk individuals in clinical settings. However, real-world factors such as resource limitations (e.g., access to technology) and patient compliance (e.g., willingness to engage with digital tools) must be considered when integrating these models into clinical workflows. Compared to existing methods, ML models offer earlier and more precise risk stratification, enabling targeted interventions before hypertension onset. These implications highlight the need for practical, evidence-based approaches to prehypertension management.

Future studies should build on this study’s findings by employing longitudinal designs to establish causal relationships between HBM constructs and blood pressure control, particularly focusing on gender-specific self-efficacy interventions or cluster-based behavioral programs. For example, longitudinal research could track the effectiveness of self-efficacy workshops in males over time or assess the impact of tailored interventions for cluster 2 individuals with lower HBM scores. Exploring continuous monitoring technologies, social support, and environmental factors could further enhance intervention efficacy. Additionally, adapting the HBM to incorporate ML insights — such as integrating predictive risk scores into perceived susceptibility — could refine its application in preventive health. Testing ML-driven interventions in diverse populations and settings will validate their clinical utility and generalizability.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the HBM, particularly through perceived severity and self-efficacy, effectively predicts blood pressure control behaviors in prehypertensive individuals. Machine learning models, especially gradient boosting (AUC = 0.895), offer robust tools for risk stratification, supporting personalized interventions. Gender and age differences highlight the need for tailored strategies, advancing the application of HBM in prehypertension management.