1. Background

Shigella species are Gram-negative bacteria responsible for shigellosis, a significant cause of bacterial bloody diarrhea worldwide. Transmission occurs primarily via the fecal-oral route, with an estimated annual burden of 188 million infections and approximately 160,000 deaths, predominantly affecting young children (1). Shigellosis remains a substantial public health challenge, particularly in developing countries where sanitation and hygiene are often inadequate (2, 3). Traditional identification of Shigella isolates through species and serotype determination is insufficient for detailed epidemiological investigations. Epidemiological analysis requires intraspecific differentiation to elucidate the origin, transmission pathways, and dynamics of outbreaks within specific geographic regions (4).

Phenotypic methods — such as biochemical testing, antibiotic susceptibility profiling, colony morphology assessments, serotyping, and phage typing — lack the discriminatory power necessary to distinguish between closely related Shigella strains or subgroups. Consequently, molecular-genetic typing methods have gained prominence for their ability to provide detailed insights into the genetic diversity, population structure, and evolutionary relationships among Shigella isolates. These techniques enhance epidemiological surveillance by enabling precise strain differentiation beyond what phenotyping methods can achieve (5).

Among molecular techniques, Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) assay utilizes short arbitrary primers (9 - 10 base pairs) to amplify diverse genomic regions, revealing polymorphisms that serve as genetic markers. Repetitive element-based PCR methods target conserved repetitive DNA sequences within bacterial genomes to generate characteristic fingerprint patterns. REP-PCR focuses on 38 base-pair repetitive extragenic palindromic (REP) sequences, which contain conserved palindromic stems interspersed with variable loop regions, and have been characterized in multiple enteric bacteria. ERIC-PCR utilizes Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus (ERIC) sequences, which are 126 base-pair elements featuring conserved central inverted repeats, initially identified in Escherichia coli but applicable across related species.

BOX-PCR targets repetitive BOX elements composed of modular subunits boxA, boxB, and boxC (59, 45, and 50 nucleotides respectively), with the BOX-A1R primer binding to the boxA subunit. The stem-loop structural configuration of these BOX elements enhances their utility in genotyping, as demonstrated in organisms such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (6-8). Despite shigellosis' high incidence in Iran (> 5,000 annual cases), phenotypic methods fail to resolve strain relatedness amid rising multidrug resistance. While international studies validate PCR fingerprinting, local data comparing ERIC-PCR, BOX-PCR, RAPD-PCR, and Rep-PCR remain scarce. This study fills this gap by evaluating their discriminatory power (Simpson's Index) on 60 clinical isolates, enabling optimized molecular epidemiology for regional surveillance.

2. Objectives

This study aims to evaluate and compare the discriminatory capabilities and epidemiological applicability of four molecular-genetic typing methods — BOX-PCR, ERIC-PCR, RAPD-PCR, and REP-PCR — in genotyping clinical Shigella isolates. Such comparative analysis will facilitate more accurate molecular epidemiological investigations and improve understanding of Shigella strain diversity within affected populations.

3. Methods

3.1. Collection and Confirmation of Shigella Isolates

Clinical Shigella isolates were collected between February 2023 and June 2023 from three sources: Milad Hospital, the microbial collection at Pasargad Research Laboratory in Tehran, and the specialized clinic laboratory of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences and Health Services. Presumptive Shigella colonies, characterized by convex morphology and colorless to slightly pink appearance on MacConkey agar, were initially selected for further analysis. These colonies underwent Gram staining followed by a series of biochemical tests to confirm genus and species identity. The biochemical assays included indole production, citrate utilization, methyl red, Voges-Proskauer, triple sugar iron (TSI), motility, urea hydrolysis, and oxidase tests, performed using standard protocols with reagents obtained from Merck, Germany (9).

3.2. Molecular Confirmation of Shigella Isolates

Genomic DNA was extracted from presumptive Shigella isolates using a commercial genomic DNA extraction kit (catalog number: DM05050, Gene Transfer Pioneer, Pishgaman Co., Tehran, Iran) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and quantity of DNA samples were assessed via spectrophotometry and agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively. Molecular identification targeted the ipaH gene, a virulence marker present in all Shigella species and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli, using the primer pair: forward 5'-GTTCCTTGACCGCCTTTCCGTTACCGTC-3' and reverse 5'-GCCGGTCAGCCACCCTCTGAGAGTAC-3' (10).

The PCR reaction was prepared in a final volume of 20 μL containing 6 μL deionized distilled water, 2.5 μL of 10X buffer, 1.5 μL of 50 mM MgCl₂, 0.2 μL of 10 mM dNTPs, 2 μL of Taq DNA polymerase, 1 μL (10 pmol) of each primer, and 2 μL DNA template (~1 pmol). Thermal cycling was performed with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 7 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 57°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 60 seconds, with a final extension step at 72°C for 7 minutes. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV illumination. The expected amplicon size was approximately 619 base pairs. Shigellasonnei ATCC 25931 served as the positive control.

3.3. Genotyping of Shigella Isolates

3.3.1. BOX-PCR

BOX-PCR was performed using the BOXA1R primer (5'-CTACGGCAAGGCGACGCTGACG-3') (11). Reactions (25 μL) contained 12.5 μL 2X Master Mix, 1 μL primer (10 pmol/μL), 2 μL template DNA (~50 ng/μL), and 9.5 μL nuclease-free water. Thermal cycling: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95°C/30 s, 52°C/1 min, 65°C/4 min (ramp rate 0.7°C/s); final extension at 72°C/10 min. Products were resolved on 1.5% agarose gels (80 V, 2.5 h) and stained with ethidium bromide.

3.3.2. Repetitive Intergenic Consensus-PCR

The ERIC-PCR utilized primers ERIC-1R (5'-ATGTAAGCTCCTGGGGATTCAC-3') and ERIC-2F (5'-AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGTGAGCG-3') (12). Reactions (25 μL): 12.5 μL 2X Master Mix, 1 μL each primer (10 pmol/μL), 2 μL template DNA, 8.5 μL nuclease-free water. Cycling conditions: 95°C/7 min; 35 cycles of 94°C/1 min, 52°C/1 min, 65°C/8 min; final extension 65°C/16 min. Amplicons were separated on 1.2% agarose gels (90 V, 3 h).

3.3.3. Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA-PCR

The RAPD-PCR employed the 10-mer primer C-05 (5'-GATGACCGCC-3') (13). Reactions (20 μL): 2 μL 10X PCR buffer, 1.5 μL MgCl₂ (50 mM), 0.2 μL dNTPs (10 mM), 0.1 μL Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μL), 1 μL primer (10 pmol/μL), 2 μL template DNA (~50 ng), 13.2 μL nuclease-free water. Cycling: 94°C/5 min; 40 cycles of 94°C/1 min, 37°C/1 min, 72°C/2 min; final extension 72°C/7 min. Products visualized on 1.5% agarose gels (100 V, 1.5 h).

3.3.4. Rep-PCR

Rep-PCR used the (GTG)₅ primer (5'-GTGGTGGTGGTGGGTG-3') (14). Reactions (25 μL): 12.5 μL 2X Master Mix, 2 μL primer (10 pmol/μL), 2 μL template DNA, 8.5 μL nuclease-free water. Thermal cycling: 95°C/5 min; 35 cycles of 95°C/30 s, 50°C/1 min, 65°C/4 min; final extension 65°C/16 min. Fragments separated on 1.5% agarose gels (80 V, 2.5 h).

3.3.5. Data Analysis

Genomic fingerprint patterns from all methods were scored as binary data (band presence = 1, absence = 0) for bands 200 - 4000 bp. Banding patterns were analyzed using NTsys-pc software version 2.02. Cluster analysis employed the Jaccard similarity coefficient with unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) clustering. Simpson's diversity Index was calculated to compare discriminatory power across methods (15). All PCR genotyping assays were performed in triplicate to ensure intra-laboratory repeatability, with consistent banding patterns observed across replicates (≥ 95% reproducibility). Typeability was 100% for all 60 isolates across methods. Inter-laboratory reproducibility was not formally assessed in this study, as the primary objective was comparative discriminatory power evaluation. NTSYS-pc version 2.02 was used for band scoring, Jaccard similarity matrix generation, and UPGMA clustering. This software is a widely validated standard for molecular epidemiology analyses, as demonstrated in numerous Shigella and Enterobacteriaceae genotyping studies.

4. Results

4.1. Biochemical and Molecular Confirmation of Shigella Isolates

A total of 60 Shigella spp. isolates were confirmed through combined biochemical and molecular analyses (ipaH PCR, 619 bp product). Species-level identification was not performed, as this study focused on comparative genotyping method evaluation.

4.2. Genetic Relatedness Among the Shigella Isolates

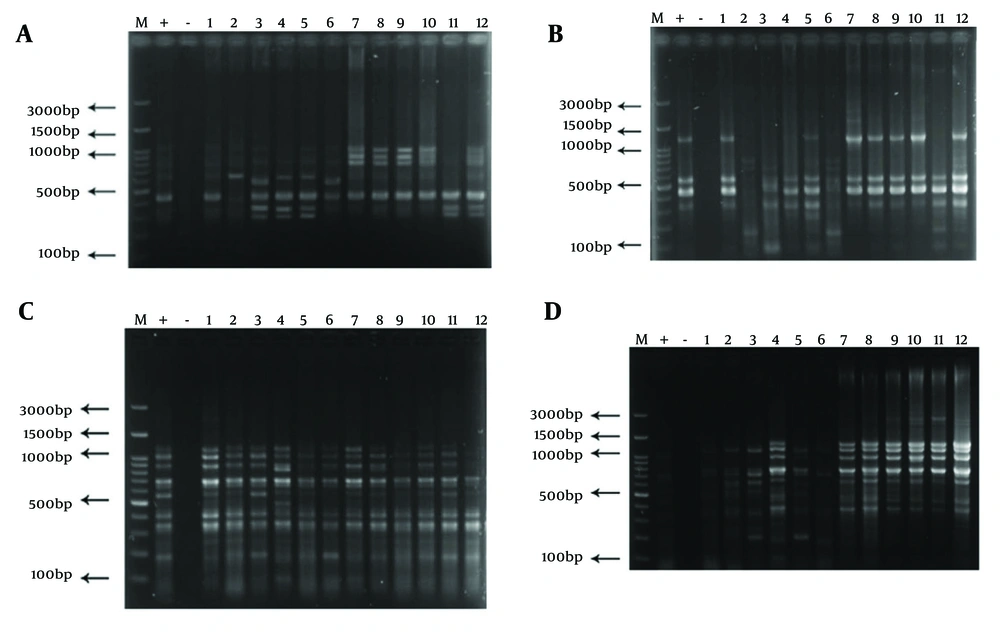

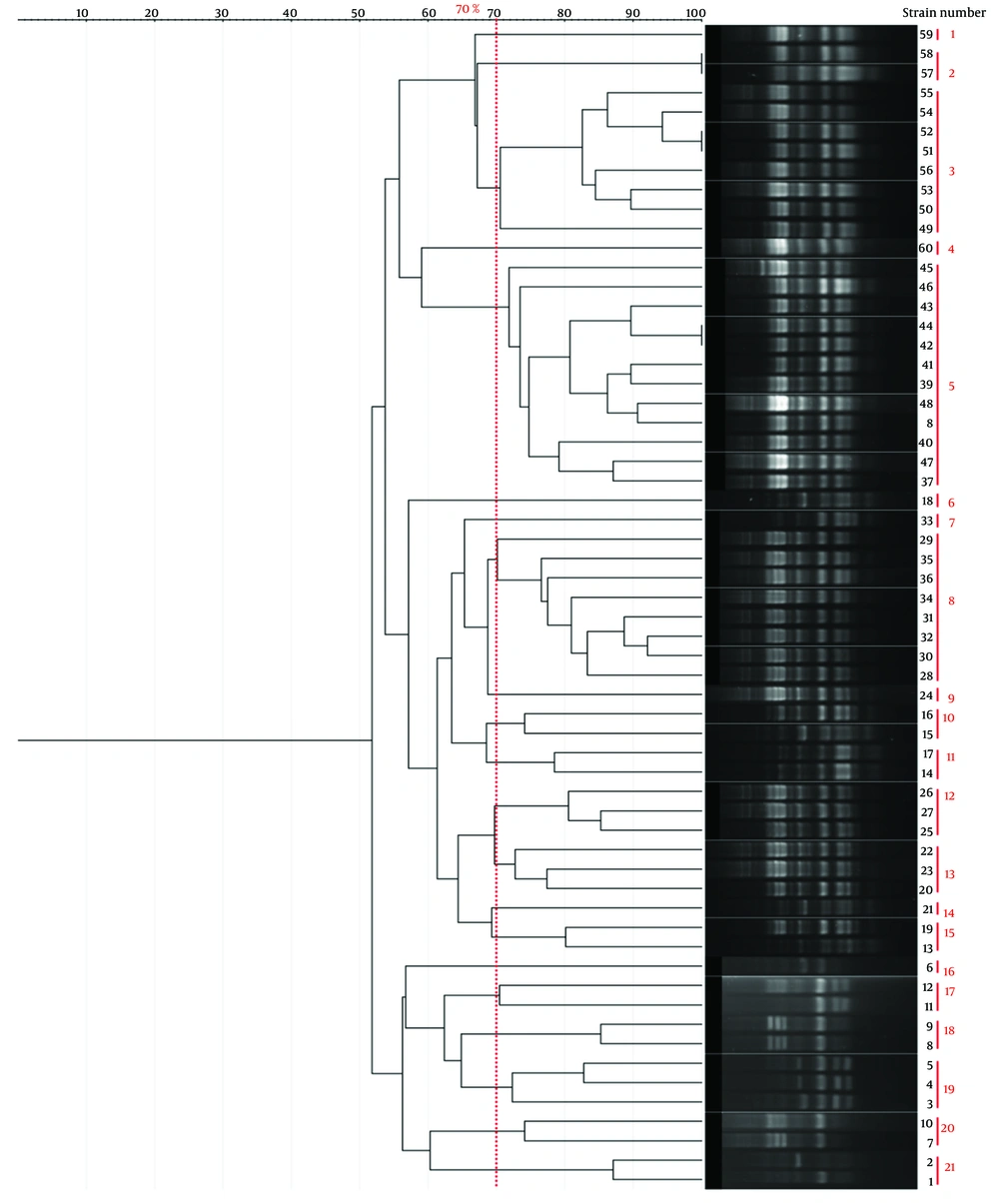

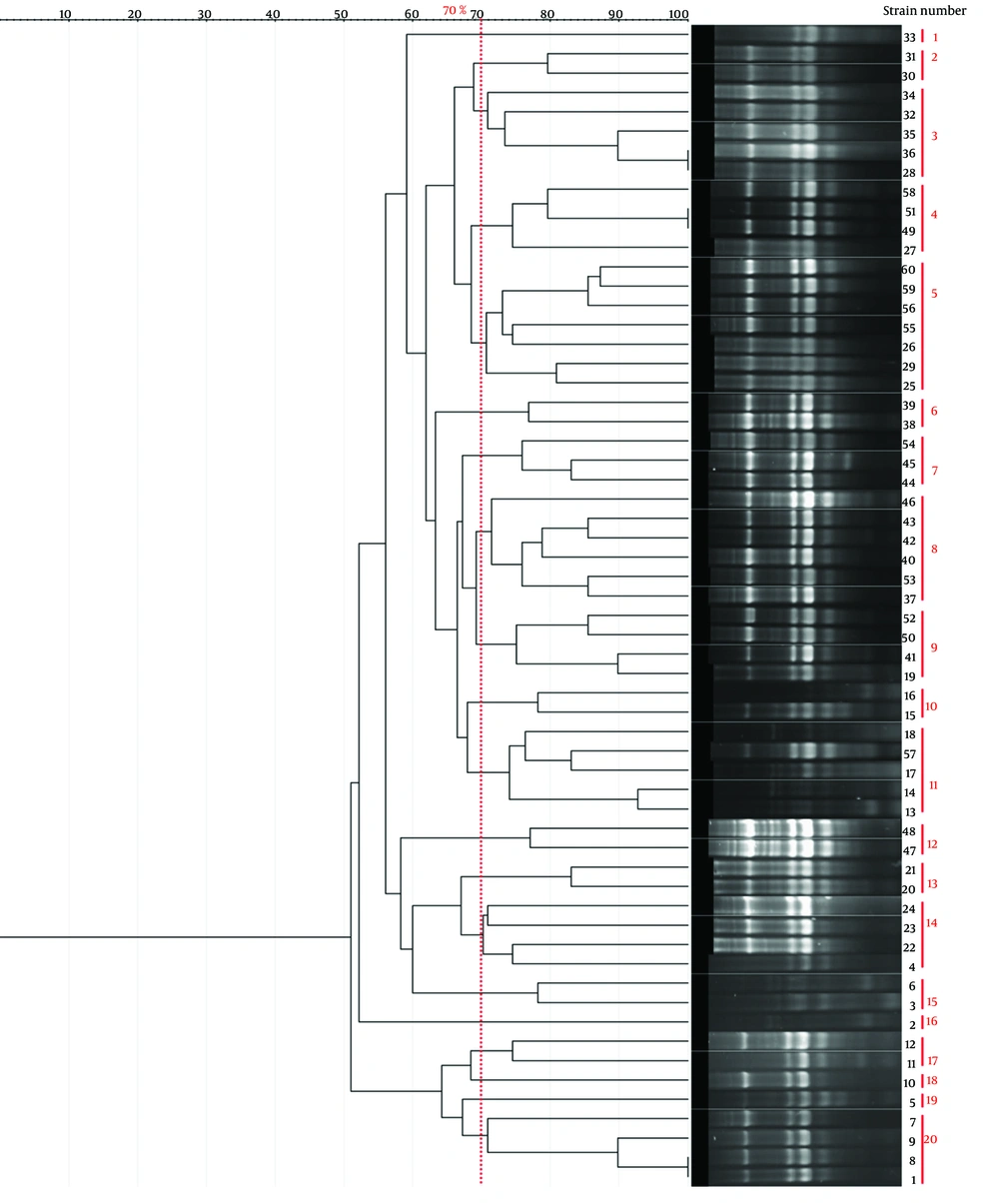

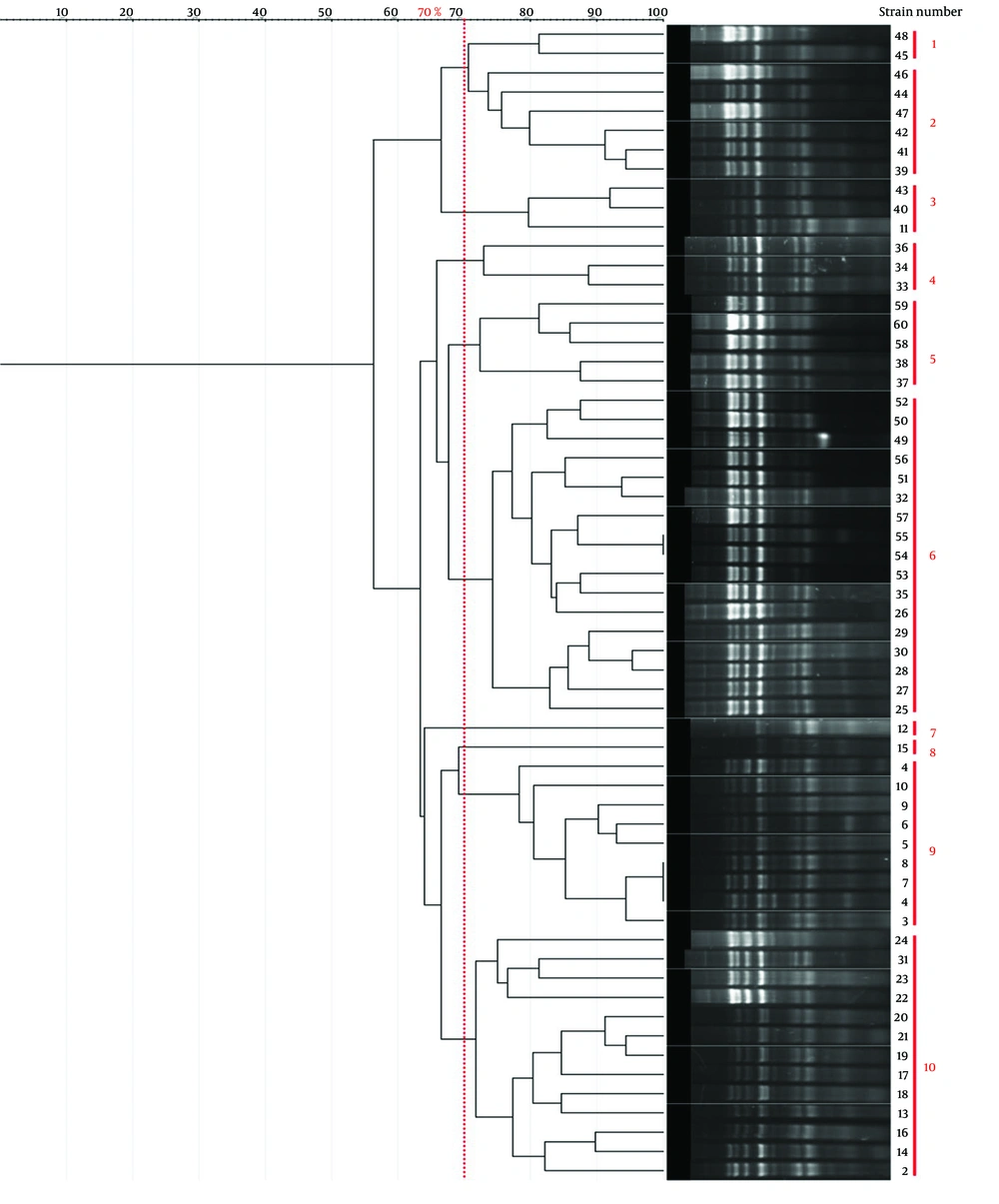

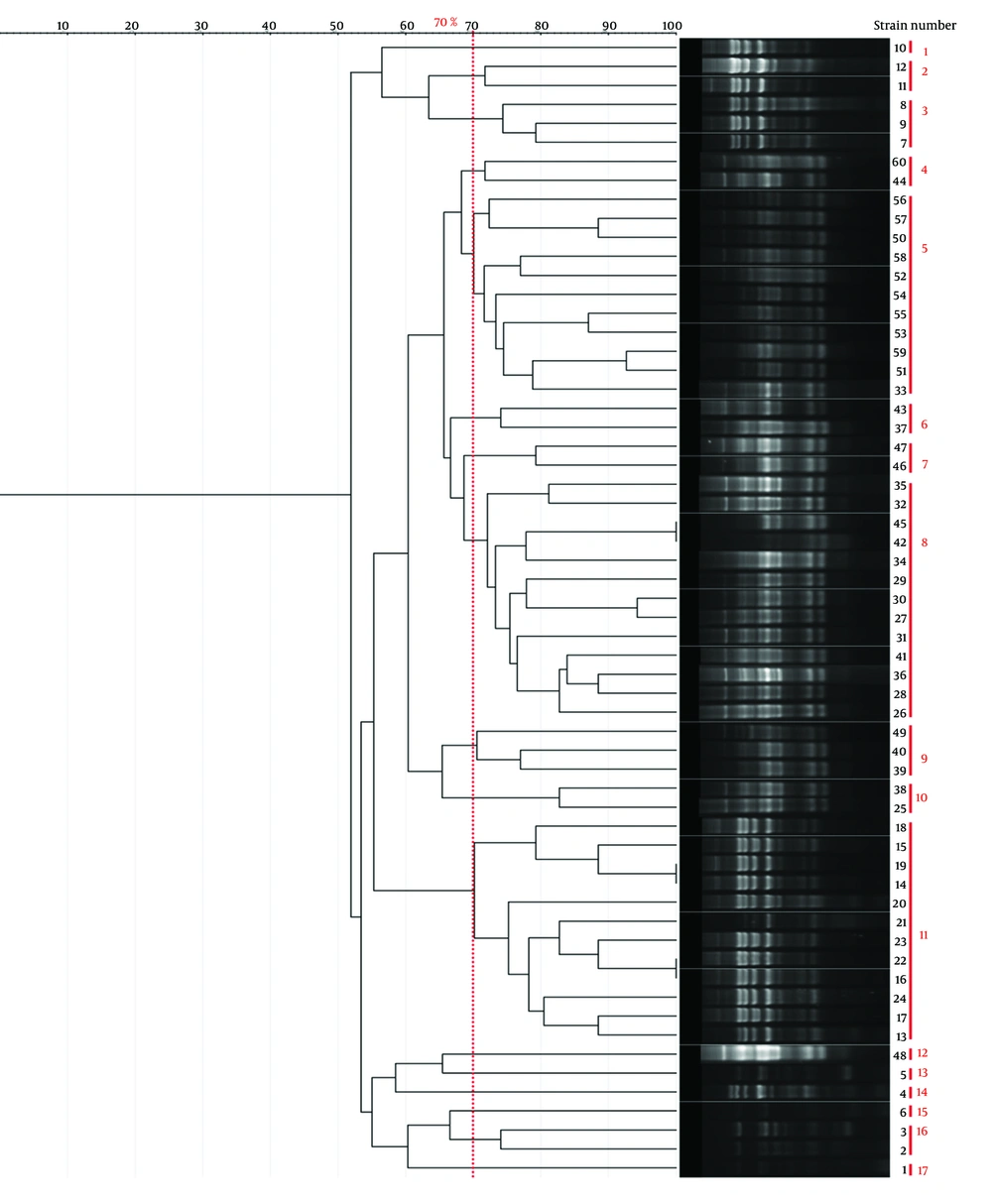

Genotyping results for all four methods are summarized in Table 1. Representative gel images are shown in Figure 1, and dendrograms in Figures 2 - 5.

| Method | No. Clusters (70% similarity) | Band Range (bp) | No. Bands/Isolate | Largest Cluster (n) | Simpson's Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOX-PCR | 21 | 100 - 3000 | 3 - 8 | 12 (Cluster 5) | 0.92 |

| ERIC-PCR | 20 | 100 - 1500 | 4 - 7 | 7 (Cluster 5) | 0.949 |

| RAPD-PCR | 10 | 100 - 3000 | -1 | 7 (Cluster 6) | 0.84 |

| Rep-PCR | 17 | 100 - 3000 | ~5 | 13 (Cluster 8) | 0.88 |

Abbreviation: ERIC, Repetitive intergenic consensus; RAPD, Random amplified polymorphic DNA; Rep, Repetitive extragenic palindromic.

BOX-PCR genotyping of Shigella isolates. A, electrophoresis of BOX-PCR product for samples 1 to 12 (M: Molecular marker, +: Positive control Shigellasonnei ATCC 25931, -: Negative control distilled water); B, ERIC-PCR product electrophoresis for samples 1 to 12 (M: Molecular marker, +: Positive control Shigellasonnei ATCC 25931, -: Negative control distilled water); C, RAPD-PCR product electrophoresis for samples 1 to 12 (M: Molecular marker, +: Positive control Shigellasonnei ATCC 25931, -: Negative control distilled water); D, Rep-PCR product electrophoresis for samples 1 to 12 (M: Molecular marker, +: Positive control Shigellasonnei ATCC 25931, -: Negative control distilled water).

5. Discussion

Shigellosis remains a critical public health challenge, particularly in developing countries where it causes significant morbidity and mortality. Traditional phenotypic methods often lack sufficient resolution to accurately discriminate between Shigella species and intraspecies variants, thereby limiting their utility in epidemiological tracking and outbreak investigation. In contrast, molecular-genetic techniques have gained increasing prominence due to their superior precision in bacterial typing and ability to provide detailed insights into the genetic structure of shigellosis-causing pathogens. The molecular approaches utilized in this study effectively overcome the inherent limitations of phenotypic assays by enabling finer intraspecies differentiation and elucidating evolutionary relationships and population dynamics among Shigella spp. (5).

In the present investigation, a total of 60 Shigella isolates were recovered from 101 clinical specimens using a combination of biochemical tests and molecular confirmation based on PCR amplification targeting the ipaH gene. To evaluate the genetic diversity and relatedness within this collection, four molecular genotyping techniques — BOX-PCR, ERIC-PCR, RAPD-PCR, and Rep-PCR — were applied.

Table 1 presents a comparison of the genotyping techniques used in this study, underscoring the enhanced discriminatory capacity of ERIC-PCR and BOX-PCR as reflected by Simpson's diversity Index. ERIC-PCR targets conserved repetitive extragenic palindromic sequences (124 - 127 bp) characteristic of Enterobacteriaceae, generating high-resolution DNA fingerprint profiles for reliable Shigella strain differentiation with excellent reproducibility and minimal equipment requirements (16, 17). While Simpson's diversity Index (D) effectively quantifies discriminatory power — ERIC-PCR (D = 0.949) and BOX-PCR (D=0.92) outperforming RAPD-PCR (D = 0.84) and Rep-PCR (D = 0.88) — additional validation metrics merit consideration. Intra-laboratory repeatability exceeded 95% across triplicate assays, confirming methodological robustness. Typeability reached 100% for all clinical isolates. NTSYS-pc v2.02 provided reliable cluster analysis consistent with published standards for PCR fingerprinting (16).

While Shigella spp. confirmation was established via ipaH PCR across all 60 isolates (Results 3.1), species-level identification (S. flexneri, S. sonnei, etc.) was outside the scope of this methodological comparison study, which focused on evaluating PCR genotyping discriminatory power across methods rather than epidemiological strain distribution. Inter-laboratory reproducibility and epidemiological correlations with clinical metadata represent valuable extensions for future studies. Species-specific identification will enable correlating genotypes with clinical outcomes and resistance profiles in comprehensive surveillance programs.

The effectiveness of ERIC-PCR as a genotyping technique was demonstrated by Shoja et al. (18), who characterized 45 Shigellasonnei isolates from Iranian pediatric patients using ERIC-PCR genotyping. The method resolved two major clusters with 100% similarity among epidemiologically related strains and achieved high discriminatory power, confirming its utility for outbreak investigation and strain tracking in clinical settings. ERIC-PCR's rapid turnaround, cost-effectiveness, and reproducibility make it particularly valuable for molecular epidemiology of shigellosis in endemic regions (18). Moreover, Bakhshi et al. (19) demonstrated the high efficacy of ERIC-PCR combined with REP-PCR in genotyping multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates, achieving excellent discriminatory power and resolving strain clusters that correlated with resistance profiles. This underscores ERIC-PCR's superior resolution and reproducibility for molecular epidemiological investigations in hospital settings (19).

The findings from previous studies are consistent with our results, confirming that ERIC-PCR exhibits superior effectiveness in genotyping Shigella strains, as evidenced by the highest Simpson’s diversity Index of 0.949 in our analysis. In comparison, BOX-PCR demonstrated the second-highest discriminatory power, with a coefficient of 0.92. This reinforces the reliability of ERIC-PCR, underscoring its potential as a robust and reproducible method capable of generating high-resolution genetic fingerprints, particularly for Shigella species. Satija and Anjankar (20) demonstrated the utility of BOX-PCR in characterizing multidrug-resistant Shigellaflexneri clinical isolates, where it effectively resolved strain diversity alongside MLST analysis and identified resistance-associated clusters. They emphasized BOX-PCR as a powerful and reliable tool for detailed molecular epidemiological analyses of Shigella in clinical settings (20). These findings highlight the importance of selecting genus-specific primers to maximize the discriminatory capacity and accuracy of molecular typing. Similarly, although BOX-PCR ranks just below ERIC-PCR in our Shigella isolates, it remains a valuable method offering substantial resolution for molecular epidemiology and strain differentiation.

Crucial criteria for assessing molecular typing methods include ease of interpretation, reproducibility of results, and discriminatory power. These factors collectively determine the method’s utility and reliability for accurate bacterial strain differentiation in epidemiological and clinical contexts (21). The overall reliability of a molecular typing method is largely dependent on its reproducibility, which is typically evaluated by repeatedly generating consistent and identical fingerprint patterns from representative isolates. Such reproducibility ensures the method’s robustness and confidence in differentiating bacterial strains in diverse epidemiological investigations (20, 22, 23). As demonstrated by Bilung et al. , both BOX-PCR and ERIC-PCR exhibited high reproducibility when applied to pathogenic Leptospira isolates, underscoring their reliability as molecular typing methods for differentiating closely related bacterial strains in epidemiological studies (24). Similarly, Spinler et al. (6) reported high reproducibility when using rep-PCR methods including BOX-PCR for genotyping multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates, demonstrating >95% concordance with whole genome sequencing and reliable DNA fingerprint patterns for epidemiological investigations. This confirms the robustness of repetitive-element PCR approaches for tracking transmission in hospital settings (6).

Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA PCR (RAPD-PCR) is a widely utilized genotyping technique that employs short, arbitrary primers to amplify random segments of genomic DNA under relatively mild PCR conditions (25). This method does not require prior knowledge of the target organism’s DNA sequence, as the primers anneal at multiple random sites across the genome, producing unique banding patterns that serve as genetic fingerprints for strain differentiation. RAPD-PCR has been effectively applied in various epidemiological studies, including the investigation of a 2010 dysentery outbreak in Yakutia, where it facilitated the confirmation of S. flexneri isolates from diverse sources (5). Furthermore, Pakbin et al. (26) demonstrated that combining ERIC-PCR and RAPD-PCR with high-resolution melting (HRM) analysis provides an effective approach for differentiating non-dysenteric Shigella species. Their results showed that the RAPD-PCR-HRM method exhibited superior diagnostic performance, achieving a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 85%. In contrast, the ERIC-PCR-HRM assay displayed markedly lower sensitivity and specificity, at 33% and 46%, respectively, indicating inferior effectiveness in this context.

Despite RAPD-PCR's known limitations related to reproducibility inherent to DNA fingerprinting techniques, the integration of HRM analysis appeared to mitigate these issues, positioning RAPD-PCR-HRM as a promising alternative for identifying non-dysenteric Shigella species in clinical specimens. This study underscores the potential for molecular-genetic approaches, particularly when combined with precise melting curve analysis, to enhance the resolution and accuracy of Shigella species identification in epidemiological investigations (26). In contrast, RAPD-PCR exhibited the lowest discriminatory power among the genotyping methods evaluated in our study, with a Simpson’s diversity Index of 0.84. As outlined in Table 2, each molecular typing technique presents distinct advantages and limitations. Therefore, careful evaluation of these characteristics is essential to select the most suitable method for accurate bacterial strain differentiation in epidemiological and clinical contexts.

| Genotyping Method | Simpson's Diversity Index | Clusters (70% Similarity) | Advantages | Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERIC-PCR | 0.949 | 20 | High resolution, cost-effective, reproducible | Standardization challenges, limited genomic coverage | (18) |

| BOX-PCR | 0.92 | 21 | High resolution, versatile | Complex interpretation, requires expertise | (27) |

| Rep-PCR | 0.88 | 17 | Reliable, cost-effective | Optimization required, lower resolution for close strains | (28) |

| RAPD-PCR | 0.84 | 10 | Rapid, minimal sample needed | Poor reproducibility, low resolution | (19) |

Abbreviation: ERIC, Repetitive intergenic consensus; Rep, Repetitive extragenic palindromic; RAPD, Random amplified polymorphic DNA.

Repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR (Rep-PCR) and related fingerprinting methods have demonstrated broad applicability for genotyping diverse bacterial species across multiple genera. Recent evaluations confirm their effectiveness for strain differentiation at subspecies levels in clinical and environmental settings (11). An automated Rep-PCR typing system significantly enhances efficiency and inter-laboratory reproducibility through optimized PCR chemistry, microfluidics-based fragment separation, and computer-assisted analysis, reducing processing time while maintaining high discriminatory power for clinical surveillance (6). In a study by Shin et al. (29), rep-PCR using newly designed repetitive sequence primers was effectively applied to genotype Mycobacterium intracellulare clinical isolates, demonstrating high reproducibility (95-98% similarity) and resolving 7 distinct clusters that correlated with VNTR epidemiological typing. The method generated fingerprint patterns with statistical correlation (Cramer's V = 0.814) to gold standard methods, highlighting rep-PCR's robustness for detailed bacterial strain differentiation and transmission tracking in clinical settings (29).

In our study, Rep-PCR demonstrated lower discriminatory resolution for genotyping Shigella isolates compared to ERIC-PCR; however, it still produced meaningful clustering patterns, underscoring its value as a reliable genotyping tool for bacterial species differentiation. Supporting the utility of these fingerprinting methods, Ekundayo and Okoh (28) investigated the genetic diversity of Plesiomonas shigelloides isolates using both ERIC-PCR and (GTG)₅-PCR techniques. Their analysis employed neighbor-joining clustering based on the Euclidean similarity Index and revealed that ERIC-PCR grouped 48 isolates into eight distinct clades, while (GTG)₅-PCR classified 34 isolates into seven clades. Although both methods demonstrated discriminatory capability, ERIC-PCR consistently exhibited greater resolution, aligning with its recognized higher discriminatory power in molecular typing studies (28). Additionally, the findings of Tahmasbi et al. on phenotypic and genotypic antibiotic resistance profiles of clinical Shigella isolates from Tehran emphasize the critical need to incorporate genotyping data into comprehensive pathogen surveillance programs to better understand resistance dissemination alongside strain diversity (30).

Moreover, studies from Iran focusing on molecular serotyping and genotyping of clinically relevant bacteria further contextualize our work. Gharabeigi et al. characterized molecular serotypes and antibiotic resistance profiles of group B Streptococcus strains from Iranian pregnant women with urinary tract infections, underscoring the importance of integrating molecular genotyping and resistance analysis in clinical settings (31). Complementary work by Banaei et al. employed BOX-PCR to genotype Streptococcus agalactiae isolates, demonstrating the method’s utility in profiling colonization genes and genetic diversity among clinical strains in Tehran (11). These studies collectively highlight the broad applicability and significance of PCR-based genotyping tools, including BOX-PCR and ERIC-PCR, in bacterial pathogen surveillance across different species and clinical contexts within Iran, reinforcing the relevance of our findings for Shigella epidemiology and molecular characterization in the region. This methodological comparison establishes baseline discriminatory capacities for future epidemiological applications when integrated with clinical metadata.

5.1. Conclusions

This study compared four molecular-genetic methods — ERIC-PCR, BOX-PCR, RAPD-PCR, and Rep-PCR — for genotyping clinical Shigella isolates, following biochemical and molecular confirmation. ERIC-PCR demonstrated the highest discriminatory power and reproducibility, establishing itself as a highly effective and reliable genotyping tool. BOX-PCR also offered strong resolution, reinforcing its potential use in epidemiological studies. RAPD-PCR and Rep-PCR exhibited moderate resolution but remain valuable for preliminary or complementary analyses. Given their specificity, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness, we recommend integrating ERIC-PCR and BOX-PCR into routine public health surveillance and outbreak investigations of Shigella infections. These methods can enhance understanding of Shigella genetic diversity and transmission dynamics, ultimately contributing to improved shigellosis control. Future work involving larger isolate collections and incorporation of additional molecular approaches will further validate and refine genotyping protocols, fostering more comprehensive monitoring and control of Shigella outbreaks.