1. Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a Gram-negative, catalase- and oxidase-positive bacillus and opportunistic pathogen capable of thriving under diverse environmental conditions. It has been isolated from various sources, including water, soil, and certain foods such as raw milk and fish (1). Pseudomonas aeruginosa is recognized as one of the primary causes of nosocomial infections; however, this versatile organism is also well-known in the food, medical, and agricultural industries (2, 3). Due to its relatively high growth rate at low temperatures (e.g., refrigeration) and broad metabolic adaptability, P. aeruginosa is more commonly associated with opportunistic nosocomial infections than with foodborne illnesses, although its involvement in food contamination poses a significant threat to food safety (3, 4).

Strains of P. aeruginosa are frequently isolated from water sources and are considered microbial indicators for assessing the hygienic quality of drinking water. Its ability to form biofilms enables this pathogen to colonize purification filters and transmission systems, which are not easily decontaminated by standard sterilization and sanitation procedures. This contributes to contamination of water reservoirs and treatment infrastructure. Moreover, due to their high proteolytic and saccharolytic activities, Pseudomonas strains can be transmitted from contaminated water, soil, and fertilizers to raw fruits, vegetables, and meat products during washing, slicing, and packaging processes — posing elevated health risks associated with the consumption of these raw foods (3).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa has also been isolated from pharmaceutical manufacturing environments, particularly from moist and wet surfaces, where it can lead to cross-contamination of pharmaceutical products. More than 80% of these isolates are capable of forming biofilms on surfaces and exhibit resistance to most antibiotics and disinfectants commonly produced or used in pharmaceutical facilities (5). Due to its high levels of resistance to a broad spectrum of antibiotics, developing effective antibacterial strategies against Pseudomonas strains remains a significant global challenge. Efflux pump systems and the production of antibiotic-hydrolyzing enzymes, such as β-lactamases, are recognized as major resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonas species (6, 7). The ability to form biofilms confers several advantages to P. aeruginosa, including protection against host immune responses, antibiotic treatments, disinfectants, sanitation procedures, and certain antimicrobial additives found in cosmetic and hygiene products (8, 9). These unique characteristics make this pathogen a serious microbial concern across the cosmetic, hygiene, pharmaceutical, and food industries (10).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has published a global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, highlighting the urgent need for new antibiotics and antimicrobial agents. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ranks as a critical priority on this list due to its high levels of resistance and clinical relevance. While the development of novel antimicrobial compounds is essential, preventing infectious diseases and minimizing antibiotic misuse in both humans and animals are equally important strategies in combating antibiotic resistance (11, 12). This study aims to investigate the mutual effects of co-culturing two P. aeruginosa strains, with a focus on their antibiotic resistance profiles and biofilm formation characteristics. Although numerous studies have investigated antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa, the role of inter-strain interactions under co-culture conditions and their impact on these traits has received less attention (13, 14). This issue is particularly important in polymicrobial environments, where strain behavior may shift in the presence of others, complicating efforts to control this pathogen.

2. Objectives

In the present study, P. aeruginosa isolates were examined both in monoculture and co-culture settings to assess how such interactions influence antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation ability.

3. Methods

3.1. Bacterial Isolation

Ten P. aeruginosa isolates were collected from diverse sources during spring and summer 2023: Clinical (human, 1 isolate), animal (leech, 2 isolates), food (cow milk, 3 isolates), and environmental (water, 3 isolates). Identification was confirmed through Gram-staining and biochemical assays, including oxidase, catalase, urease activity, sugar fermentation in triple sugar iron (TSI) medium, and oxidation-fermentation (OF) tests. Differentiation was performed using selective cetrimide agar. All isolates were preserved at -20°C in tryptic soy broth (TSB) supplemented with 20% glycerol. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27835 served as the reference strain.

3.2. Bacterial Identification by Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay

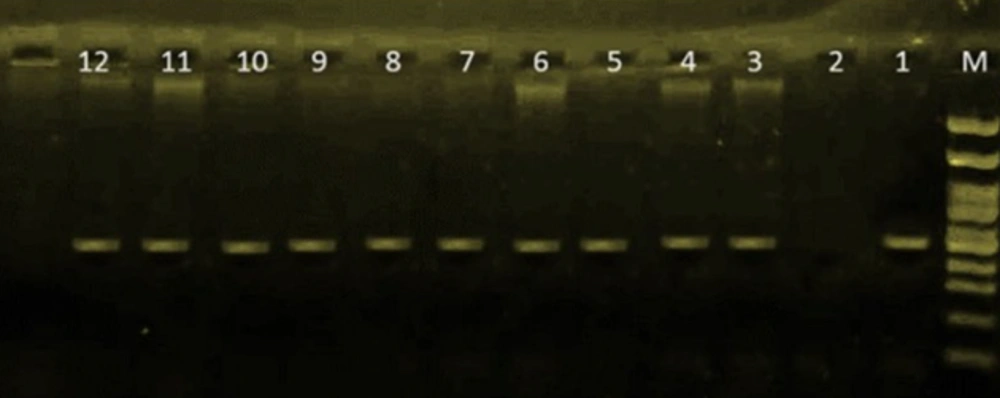

DNA of the isolates was extracted by using the boiling method. All P. aeruginosa isolates were identified by detection of the OprL gene using specific primers. The forward and reverse primer sequences were 5′-ATGGAAATGCTGAAATTCGGC-3′ and 5′-CTTCTTCAGCTCGACGGCGCGACG-3′, respectively. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in a 25 μL final reaction volume as described in Table 1. Distilled sterilized water and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27835 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. The PCR products (504 bp) were characterized and identified by gel electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel for 1 hour at 100 V; results are shown in Figure 1 (15). The PCR condition includes:

- Amplicon (bp): 504

- Primer sequence (5′-3′): ATGGAAATGCTGAAATTCGGC, CTTCTTCAGCTCGACGCGACG

- Target gene: OprL-F, OprL-R

- Final extension: 72°C, 10 min

- Cycles: 35×

- Extension: 72°C, 1 min

- Annealing: 59°C, 1 min

- Denaturation: 94°C, 1 min

- Pre-denaturation: 94°C, 10 min

| Target Genes | Primer Sequence (5’-3’) | Amplicon (bp) | PCR Condition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-denaturation | Denaturation | Annealing | Extension | Cycles | Final Extension | |||

| OprL-F | ATGGAAATGCTGAAATTCGGC | 504 bp | 94°C, 10 min | 94°C, 1 min | 59°C, 1 min | 72°C, 1 min | 35X | 72°C, 10 min |

| OprL-R | CTTCTTCAGCTCGACGCGACG | |||||||

Abbreviation: PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

3.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Susceptibility of P. aeruginosa isolates to different antibiotics was evaluated using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Merck, Germany) according to the procedures recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI M100, 2025) (16). Antibiotic disks (PadTan Teb Co., Tehran, Iran) tested were amikacin (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), imipenem (10 μg), meropenem (10 μg), levofloxacin (5 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), piperacillin (100 μg), colistin (10 μg), amoxicillin (25 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), cefepime (30 μg), cefixime (5 μg), ceftiofur (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), enrofloxacin (5 μg), florfenicol (30 μg), fosfomycin (200 μg), kanamycin (30 μg), lincomycin (2 μg), ofloxacin (5 μg), penicillin (10 units), sultrim (15 μg), and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 μg). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a control for antibiotic susceptibility testing.

3.4. Preparation of Two-Strain Bacterial Suspension

Colonies of two strains were transferred to sterilized tubes containing peptone water. Each microbial suspension's concentration was adjusted to the turbidity of 0.5 McFarland units and serially diluted to reach 107 CFU/mL. A 50:50 suspension of both strains was mixed to prepare a two-strain bacterial suspension, obtaining a microbial concentration of 108 CFU/mL, and used for further analysis (17).

3.5. Biofilm Formation Assay

Biofilm formation characteristics of P. aeruginosa isolates were evaluated using the tissue culture plate method described by Mathur et al., with a modification in incubation duration, which was set at 18 hours (18). A standard microtiter plate assay was used to detect and quantify biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa isolates. Cultures were grown in TSB to 0.5 McFarland turbidity, diluted 1:100, and incubated in 96-well plates at 37°C for 18 hours. Wells were washed with PBS to remove planktonic cells, fixed with 2% sodium acetate, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. After washing and drying, biofilm was solubilized with ethanol, and optical density (OD) was measured at 570 nm using an ELISA reader. Negative and positive controls included sterile TSB and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, respectively. All assays were performed in triplicate. Biofilm strength was classified using the optical density cut-off (ODC) method as below (19):

- Without biofilm formation: The OD ≤ ODC

- Weak biofilm formation: The ODC < OD ≤ 2 × ODC

- Strong biofilm formation: 2 × ODC < OD ≤ 4 × ODC

- Very strong biofilm formation: The OD > 4 × ODC

4. Results

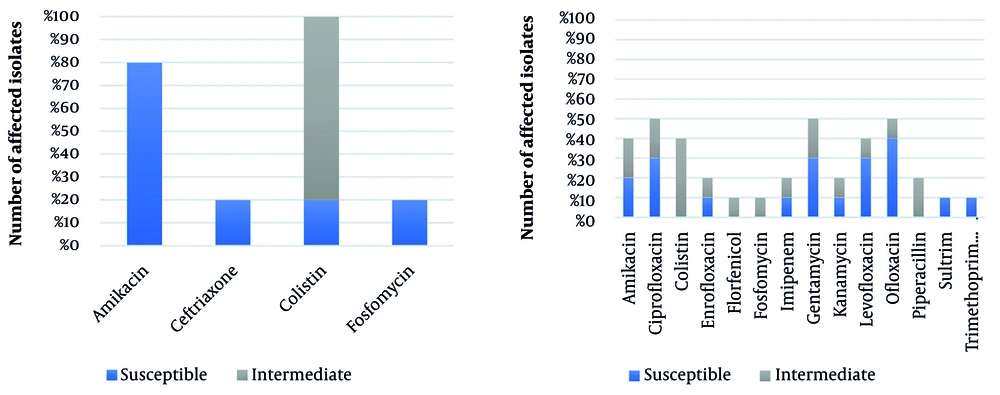

Antibiotic susceptibility of P. aeruginosa isolates and the reference strain, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, are shown in Table 2. All P. aeruginosa isolates were resistant to amoxicillin, ampicillin, cefepime, cefixime, ceftiofur, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, erythromycin, lincomycin, meropenem, and penicillin antibiotics. As described in Table 2 , P. aeruginosa strains P1, P7, and P9 were resistant to all antibiotics used in this study. Since the P. aeruginosa isolate P1 was detected as the most antibiotic-resistant isolate in this study, this isolate was selected for the co-culture antibiotic resistance evaluation model and co-cultured with five other isolates, including P. aeruginosa isolates P2, P3, P6, P8, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 as PC. Co-culture antibiotic susceptibility of these isolates is described in Table 3.

| Strain’s Name | Strain’s Source | Susceptible Antibiotics | Intermediate Antibiotics | Biofilm Formation Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Water | - | - | Moderate |

| P2 | Water | Amikacin, gentamycin, kanamycin | - | Low |

| P3 | Cow’s milk | Gentamycin, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin | - | Moderate |

| P4 | Cow’s milk | Gentamycin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin | - | Moderate |

| P5 | Cow’s milk | - | Colistin | Low |

| P6 | Cow’s milk | Ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, amikacin, imipenem, gentamycin, piperacillin | - | Low |

| P7 | Leech | - | - | Moderate |

| P8 | Human | - | Colistin | High |

| P9 | Leech | - | Amikacin | Low |

| P10 | Water | Amikacin, ciprofloxacin, enrofloxacin, imipenem, kanamycin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin, sultrim, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, colistin, florfenicol, piperacillin | - | Low |

| PC | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | Ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin, amikacin, colistin, enrofloxacin, fosfomycin, gentamycin | - | Low |

| Strain’s Name | Susceptible Antibiotics | Intermediate Antibiotics | Biofilm Formation Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1-P2 | Amikacin, fosfomycin | Ceftriaxone, colistin | None |

| P1-P3 | Amikacin, colistin | - | Low |

| P1-P6 | Amikacin, colistin | - | None |

| P1-P8 | - | Colistin | Low |

| P1-PC | Amikacin, colistin | - | Low |

a The rest of co-cultures are given in Figure 2.

In the co-culture model, 50% of P. aeruginosa isolates showed susceptibility to ofloxacin, gentamycin, and ciprofloxacin. Amikacin, ceftriaxone, colistin, and fosfomycin also inhibited growth in at least one co-culture pair. Over 80% of co-cultured isolates were fully susceptible to amikacin, contrasting with mono-culture results where strains P2 and P6 (and the reference strain) showed only susceptible or intermediate responses. All co-cultured isolates were susceptible to colistin, while in mono-culture, only isolate P8 and the reference strain were intermediate. These findings indicate that co-culturing significantly alters antibiotic resistance profiles. The dataset used for this analysis is summarized in Figure 2.

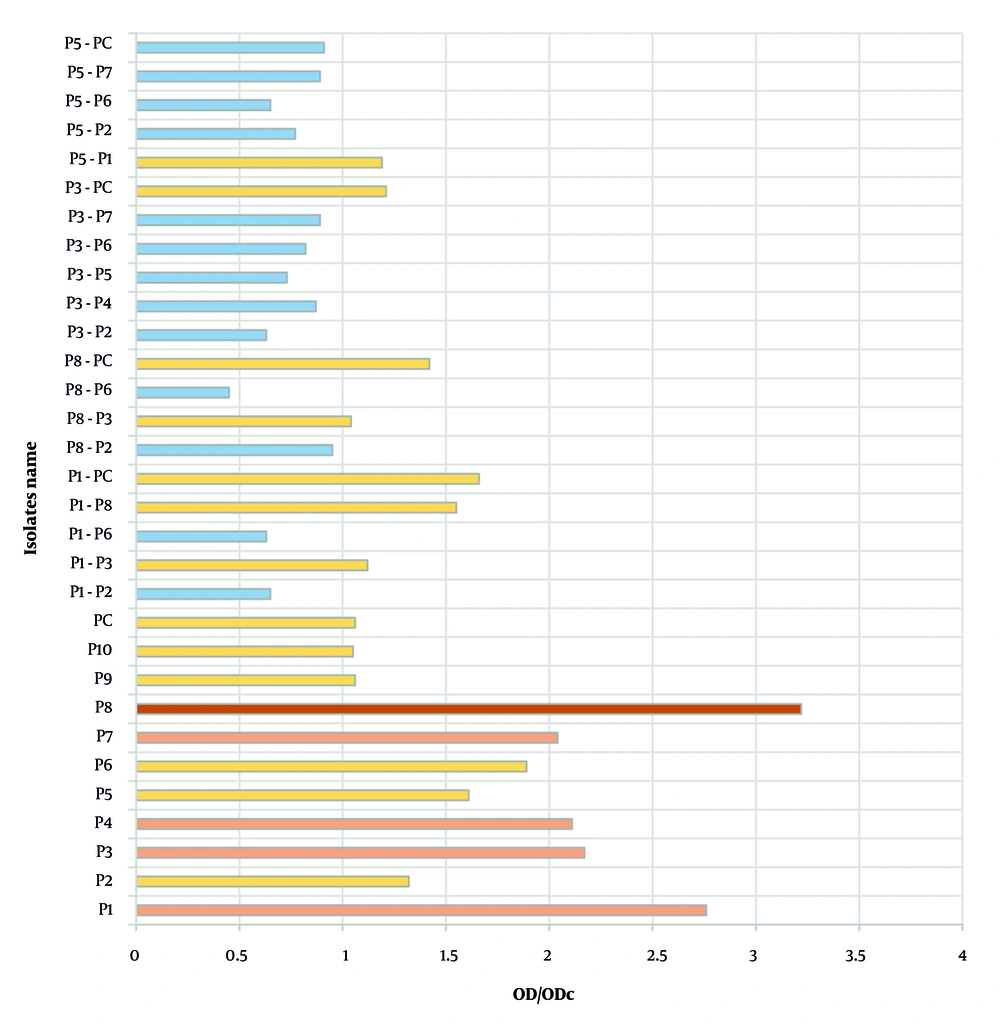

Biofilm production was assessed in both mono-culture and co-culture models using the tissue culture plate assay. All P. aeruginosa isolates formed biofilms in mono-culture: Isolate P8 produced a very strong biofilm, while P1, P3, P4, and P7 formed strong biofilms; the remaining isolates were weak producers. In contrast, 13 out of 20 co-culture combinations failed to produce biofilm, and the rest formed only weak biofilms. These results demonstrate that co-culturing significantly alters biofilm formation capacity compared to mono-culture conditions. The corresponding data are presented in Figure 3.

5. Discussion

Several recent studies have shown that co-culture growth of Pseudomonas species can significantly influence key behaviors of these bacterial pathogens, including antibiotic resistance, pathogenic mechanisms, virulence, and biofilm formation characteristics (17). These interactions may exert both inhibitory and promotive effects on strain behavior within co-culture systems. Jiang et al. demonstrated that Bacillus species can reduce the expression of virulence factors in P. aeruginosa by inactivating acyl-homoserine lactone-based quorum sensing systems in co-culture (20). Pseudomonas aeruginosa thrives in microbial consortia where diverse interactions occur; consequently, these organisms are rarely found in isolation in natural environments. In a synthetic co-culture study, Pflueger-Grau et al. reported that P. putida co-cultured with Synechococcus elongatus exhibited significantly greater resistance to environmental stresses compared to monoculture conditions (21).

This study examined the antibiotic resistance profiles of 10 P. aeruginosa isolates against 26 commonly used antibiotics. Notably, isolates P1, P7, and P9 — sourced from marine and freshwater environments — exhibited complete resistance under mono-culture conditions. However, when isolate P1 was co-cultured with five other strains, its resistance profile shifted significantly. Co-culture conditions revealed increased susceptibility to certain antibiotics, even among isolates previously resistant to all tested drugs. These findings suggest that inter-strain interactions in co-culture can modulate resistance behaviors, potentially enhancing antibiotic efficacy. Nonetheless, co-infections involving such pathogens may still lead to more severe disease outcomes and higher mortality rates, highlighting the complexity of treating polymicrobial infections (22). In the present study, two P. aeruginosa isolates that were resistant to amikacin in mono-culture became susceptible under co-culture conditions. Further investigation is warranted to better understand this phenomenon. Exploring D-amino acid profiles may also provide valuable insights, as all P. aeruginosa isolates in this study demonstrated strong biofilm-forming capacity.

Several key factors — such as interspecies interactions and nutrient competition — can significantly influence biofilm formation in co-cultures. These factors may exert either inhibitory or promotive effects on the biofilm-forming behavior of bacterial pathogens. In the present study, biofilm formation capacity decreased across all P. aeruginosa isolates; notably, some isolates in co-culture failed to produce any biofilm, while others formed only weak biofilms. The interaction between two strains in co-culture appears to play a central role in modulating biofilm development.

As previously reported by Yang et al., the wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain facilitates microcolony formation in Staphylococcus aureus, thereby promoting biofilm development. However, other mutants did not induce any significant changes in S. aureus biofilm formation (23). In addition to synergistic interactions, co-cultured strains may also engage in inhibitory interactions. These inhibitory dynamics can be effectively leveraged for biocontrol of plant pathogens in agricultural systems. Regarding the inhibitory mechanisms associated with Pseudomonas strains, certain species of this opportunistic pathogen — such as P.corrugata — are capable of releasing lipodepsipeptides with antimicrobial activity. These compounds may suppress biofilm formation or disrupt existing biofilms produced by other Pseudomonas strains in competitive settings (24).

In the studies by Saeli et al. and Jafari-Ramedani et al. and, persistent resistance to colistin and amikacin was reported in clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. In contrast, the present study revealed that under co-culture conditions among environmental isolates, susceptibility to both antibiotics increased, and biofilm formation capacity was notably weakened (25, 26). These differences are likely driven by inter-strain interactions and environmental factors, suggesting that antibiotic resistance can be modulated by culture conditions and microbial dynamics. Similarly, Olana et al. reported a significant correlation between biofilm intensity and multidrug resistance in clinical isolates (27). However, our findings showed that biofilm formation was reduced under co-culture conditions, alongside increased sensitivity to colistin and amikacin. These observations reinforce the idea that resistance is not solely determined by genotype, but can be influenced by ecological interactions and growth context. Unlike previous studies that focused on interspecies co-culture models such as P. aeruginosa with S. aureus (28), our study examined intraspecies interactions and demonstrated that these dynamics can also significantly affect antibiotic resistance and biofilm development.

5.1. Conclusions

These findings may provide a foundation for designing targeted combination therapies based on intraspecies ecological behavior. Given the transmission of P. aeruginosa and its metabolites through water, food, and hygiene products, addressing its multidrug resistance is critical for public health. Investigating co-culture behaviors provides valuable insights into biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance under competitive conditions. Although both intrinsic and extrinsic factors influence these dynamics, biofilm remains a central defense mechanism against medical treatment and sanitation efforts. Understanding inter-strain competition in co-cultures — such as metabolite release and quorum-sensing interactions — may inform the development of novel antimicrobial strategies. Nevertheless, further research is needed to fully elucidate these mechanisms and advance effective therapies against nosocomial infections caused by P. aeruginosa.