1. Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) is an opportunistic Gram-negative pathogen that readily causes several clinical cases, such as pneumonia (1), sepsis (2), urinary tract infections (3), and chronic lung infections in cystic fibrosis patients (4). In China, PA remains the most frequently isolated non-fermenter in nationwide surveillance, and multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MDR-PA) rates continue to rise (5). Globally, the World Health Organization has placed carbapenem-resistant PA in the highest priority tier for new antibiotic development, underscoring its threat to public health (6). A US national database study revealed that patients with respiratory infections caused by MDR-PA experienced worse outcomes compared to those with non-MDR strains. Specifically, they had higher mortality, an approximately 7-day increase in hospital length of stay (LOS), elevated readmission rates, and an additional $20,000 in healthcare costs per infection (7).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa’s success reflects a layered resistance armamentarium — β-lactamases and carbapenemases, loss of the OprD porin, and multiple RND-family efflux pumps — coupled with robust stress tolerance and biofilm formation. These features complicate empirical therapy and foster persistence under antimicrobial pressure (8). Central to PA pathogenicity and tolerance is quorum sensing (QS), a hierarchical communication network integrating the Las, Rhl, and Pqs subsystems. Autoinducer accumulation activates transcriptional regulators (LasR/LasI, RhlR/RhlI, PqsR/PQS), which in turn coordinate expression of hundreds of genes controlling biofilm maturation, pyocyanin, elastase, rhamnolipids, and other virulence determinants (9, 10). The Las system positively regulates Pqs, and Pqs can feedback to Rhl, creating a multilayered, partially redundant architecture that stabilizes virulence programs under fluctuating environments (11).

Because QS is a hub for virulence and antibiotic tolerance, antivirulence strategies have increasingly targeted QS circuitry (12). A wide spectrum of quorum-sensing inhibitors (QSIs) — macrolides such as azithromycin (13), marine-derived halogenated furanones (14), and numerous natural or synthetic analogs — can attenuate QS outputs in vitro and in animal models (15-17). Yet clinical translation has stalled. Quorum sensing networks are plastic and overlapping; bacteria can evolve resistance or reroute signaling. Many QSIs show weak potency, unfavorable pharmacokinetics, or toxicity, and randomized trials have yielded inconsistent benefits (18).

Fosfomycin (FOM), discovered more than five decades ago, irreversibly inhibits MurA — the first committed enzyme of peptidoglycan synthesis — via covalent modification, a mechanism distinct from other cell-wall agents and associated with relatively low cross-resistance (19, 20). Nwabor et al. (21) found that FOM at 0.5X the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) significantly inhibited the adhesion of Acinetobacter baumannii (AB) to surfaces and impaired biofilm maturation. Concurrently, intravenous FOM, with its favorable pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profile, antibiofilm activity, and synergistic potential with other antimicrobials, represents a promising repurposed option for combating challenging Pseudomonas infections, which are often associated with high morbidity, multidrug resistance, and biofilm formation (22). Beyond its classic antibacterial activity, FOM penetrates biofilms and frequently exhibits synergy with β-lactams, aminoglycosides, quinolones, or colistin against PA in planktonic and biofilm states (23, 24).

Research has shown that sequential administration of FOM followed by linezolid exhibited superior bactericidal activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus compared to concomitant dosing, as evidenced by static/dynamic kill assays and TEM-revealed enhanced cell wall disruption (25). In a biofilm model derived from carbapenem-resistant PA isolates of burn wound infections, FOM combined with colistin exhibited potent synergistic activity in suppressing carbapenem-resistant PA biofilm formation (26). A previous study demonstrated that FOM combinations with aminoglycosides, glycylcyclines, fluoroquinolones, or colistin exhibited synergistic activity against FOM-resistant MDR A. baumannii, reducing MICs 2- to 16-fold and achieving > 99.9% bacterial kill in time-kill assays, suggesting its potential as combination therapy pending further in vivo validation (21).

Despite accumulating evidence that sub-MIC antibiotics can modulate bacterial signaling, no systematic investigation has linked sub-inhibitory FOM exposure to direct suppression of PA QS regulators, consequent reductions in QS-controlled virulence traits (biofilm, pyocyanin, proteases), and improved pulmonary outcomes in vivo. Reviews of FOM combination therapy highlight antibiofilm synergy but still acknowledge a paucity of mechanistic data connecting FOM to QS pathways. This is the first integrated study to link sub-MIC FOM with coordinated down-modulation of Las/Rhl/Pqs transcripts, concordant suppression of pyocyanin/protease/biofilm/motility, and improved outcomes in an MDR-PA pneumonia model. We further benchmarked effects against a positive QSI control (azithromycin), verified primer performance, and clarified statistical and animal-size justifications.

2. Objectives

We discuss implications for repurposing FOM as an antivirulence adjuvant while acknowledging that putative mechanisms (e.g., acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) receptor competition or synthase interference) remain hypotheses requiring direct biochemical validation.

3. Methods

3.1. Culture Media, Chemicals, and Bacterial Strains

The culture media used in this study — including Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth, and Columbia blood agar — were purchased from Oxoid (Hampshire, UK). Agar, tryptone, and antibiotic susceptibility disks were also obtained from the same supplier. Chemical reagents such as FOM, crystal violet, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were acquired from Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology (Shanghai, China). Clinically isolated PA strains were initially cultured on Columbia blood agar plates for 24 hours. The reference strain PAO1 and the quality control strain ATCC 27853 were included in the experiments. Bacterial identification was performed using the VITEK-2 COMPACT automated microbial identification system (bioMérieux, France). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted via the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method, and 50 MDR-PA strains were selected for further study. The screened MDR-PA isolates were preserved at -80°C for subsequent experiments.

3.2. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Fosfomycin

The MIC of FOM against PAO1 was determined using the broth microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (CLSI, 2015). Various concentrations of FOM were prepared through serial two-fold dilutions in MH broth. After mixing the diluted solutions of FOM with sterilized MH agar and glucose-6-phosphate at a 9:1 ratio, 1 μL of bacterial suspension (approximately 1 × 106 CFU/mL) was inoculated onto the center of each agar plate. Plates were incubated overnight at 35°C, and the MIC was identified as the lowest concentration showing no visible bacterial growth. The MIC for PAO1 was determined to be 2 μg/mL.

3.3. Bacterial Growth Inhibition and Selection of Sub- Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

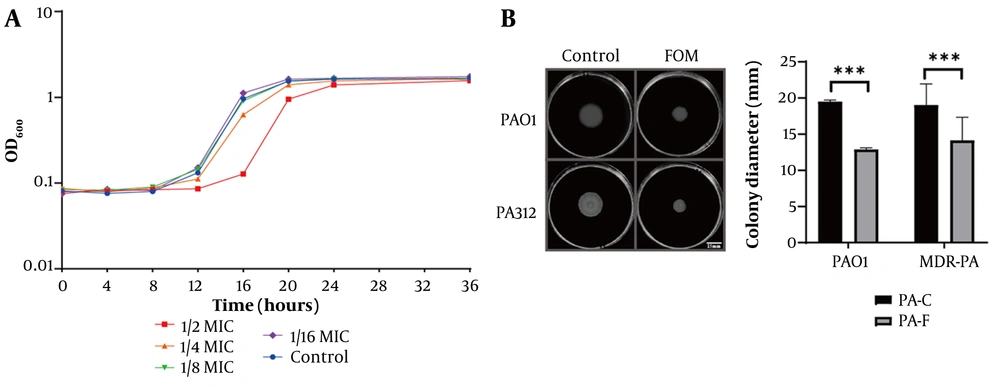

To assess the growth inhibitory effect, PAO1 bacterial suspensions (0.5 McFarland standard; approximately 1 × 108 CFU/mL) were mixed with FOM to achieve final concentrations of 1 μg/mL (1/2 MIC), 0.5 μg/mL (1/4 MIC), 0.25 μg/mL (1/8 MIC), and 0.12 μg/mL (1/16 MIC). A control group without FOM was also included. All samples were incubated at 35°C, and bacterial growth was monitored by measuring OD600 every 4 hours for 36 hours. The growth curves (Figure 1A) demonstrated that FOM concentrations of ≤ 0.5 μg/mL (1/4 MIC) did not significantly affect bacterial growth. Thus, the highest concentration that did not alter growth kinetics relative to control was 1/8 MIC (0.25 μg/mL) for both PAO1 and PA312 (Figure 1 and Figure S1A, found in Supplementary File). Therefore, 1/8 MIC was used for all sub-MIC phenotypic assays and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR).

Fosfomycin (FOM) at sub-minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) inhibits PA growth dynamics and swimming motility. A, growth curves of PAO1 in Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth with FOM at 1/2 MIC (1 μg/mL), 1/4 MIC (0.5 μg/mL), 1/8 MIC (0.25 μg/mL), 1/16 MIC (0.12 μg/mL), and control. OD₆₀₀ was measured every 4 h for 36 h. Only 1/2 and 1/4 MIC significantly delayed growth; 1/8 and 1/16 MIC overlapped with control; B, swimming motility assays on agar plates containing 1/8 MIC FOM or no drug. Colony diameters were measured after 20 h at 35°C (mean ± SD, n = 3). Sub-MIC FOM significantly reduced motility (P < 0.001). *** P < 0.001.

3.4. Determination of Biofilm Formation

Biofilm formation by PAO1 and MDR-PA was measured using sterile silicone catheter segments incubated with or without sub-inhibitory concentrations of FOM for 72 h at 35°C. Catheter segments incubated only in LB medium served as blank controls. Following incubation, catheter segments were stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution. After destaining with 95% ethanol, biofilm biomass was quantified by measuring absorbance at OD600.

3.5. Fosfomycin Stability Assay

Fosfomycin was quantified on an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC with DAD (200 nm), using an amide-HILIC column (4.6 × 150 mm, 3.5 µm) at 30 °C. Mobile phases: A = acetonitrile; B = 50 mM ammonium acetate (pH 4.5). Gradient: 85% to 70% A (0 - 8 min), hold 70% A (8 - 10 min), re-eq 85% A (10.1 - 14 min); flow 0.80 mL/min; injection 10 µL. Two bacteria-free groups were tested: Mueller-Hinton and LB media spiked to 0.25 µg/mL FOM (sub-MIC). Aliquots were collected at 0, 24, 48, 72 h during incubation at 35°C. Matrix-matched calibration 0.05 - 2.00 µg/mL (r² ≥ 0.998); LOQ 0.05 µg/mL.

3.6. Biofilm Morphology Visualization

Sterilized glass coverslips were placed in LB broth containing or lacking sub-inhibitory concentrations of FOM, followed by incubation with MDR-PA and PAO1 strains. A blank control well containing only LB broth and coverslips was included. After incubation, the coverslips were washed three times with PBS buffer, air-dried, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 minutes. Excess stain was removed by repeated PBS washes until the effluent became colorless. Biofilm formation was visualized under an optical microscope at 400 × magnification, and images were captured for analysis.

3.7. Assessment of Virulence Factor Production

This study employed three distinct methodologies to evaluate (1) bacterial swimming motility, (2) pyocyanin production, and (3) total extracellular protease activity. The specific procedures for each assay are outlined below. As a positive control for QS inhibition, azithromycin (AZM, 2 µg/mL) was included in parallel for PAO1 and selected MDR isolates (PA312, PA324) with matched Vehicle controls. Exposures were for 20 h under the same culture conditions.

3.7.1. Bacterial Swimming Motility Assay

Swimming agar plates containing sub-inhibitory concentrations of FOM were prepared using tryptone, NaCl, and agarose dissolved in distilled water. Control plates were prepared without FOM. Multidrug-resistant PA and PAO1 cultures were spot-inoculated at the center of each plate using a micropipette and incubated at 35°C for 20 h. Colony diameters were measured using a vernier caliper, with three technical replicates performed for each condition.

3.7.2. Pyocyanin Quantification

Multidrug-resistant PA and PAO1 were cultured in broth with or without sub-inhibitory FOM at 35°C for 72 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant was extracted with chloroform by vigorous shaking for 30 s, followed by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 5 min. The chloroform layer was mixed with 400 μL of 0.2 mol/L HCl, shaken for 30 s, and allowed to settle for 10 min. Upon development of a pink color in the acid layer, 200 μL was transferred to a microplate reader, and absorbance was measured at OD520.

3.7.3. Total Extracellular Protease Activity

Proteolytic activity was assessed using a modified skim milk assay (27). Bacterial cultures were grown in broth with or without sub-inhibitory FOM at 35°C for 24 h. After centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was mixed with 2 mL of 1.25% skim milk solution and incubated in a metal bath at 35°C for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at OD600 using a microplate reader.

3.8. Gene Expression Analysis by Quantitative Real-time PCR

Based on culture media containing or lacking sub-inhibitory concentrations of FOM, the clinically isolated MDR-PA strains and PAO1 were divided into two groups: PA-F (PA-FOM) and PA-C (PA-control). After 20 hours of incubation at 35°C, total RNA was extracted from the cultures using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) via the lysis-adsorption method, followed by cDNA synthesis using a commercial kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA concentration and purity were determined using a multifunctional microplate reader (Implen, Munich, Germany).

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the LightCycler® 480 SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche, Germany) in a final reaction volume of 20 μL. The 16S rRNA gene served as the housekeeping control, and relative gene expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method. Primer specificity and efficiency were validated according to MIQE guidelines. Ten-fold serial dilutions of pooled cDNA (106 - 101 copies equivalent; 6 points, in triplicate) were used to generate standard curves on the LightCycler 480. Slopes and determination coefficients (R²) were calculated, and amplification efficiency (E) was derived as E = (10(−1/slope) − 1) × 100%. Assays were accepted if 90 - 110% efficiency, R² ≥ 0.99, single-peak melt curve, and no amplification in NTC/-RT controls. Primer sequences used in this study are listed in Table 1.

| Gene Names (Ref) | Primer Sequence (5'→3') | Amplicon Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA (28) | 137 | |

| F | GGCTCAACCTGGGAACTGCA | |

| R | CAGTATCAGTCCAGGTGGTCGC | |

| LasR (28) | 183 | |

| F | GCAGCACGAGTTCTTCGAGG | |

| R | GCGTAGTCCTTGAGCATCCAC | |

| LasI (28) | 153 | |

| F | CCGTTTCGCCATCAACTCTGG | |

| R | CGGATCATCATCTTCTCCACGC | |

| RhlR (28) | 150 | |

| F | CGCCACACGATTCCCTTCAC | |

| R | GCTCCAGACCACCATTTCCGA | |

| RhlI (29) | 123 | |

| F | GCTACCGGCATCAGGTCTTC | |

| R | GGCTCATGGCGACGATGT | |

| PqsR (30) | 238 | |

| F | AACCTGGAAATCGACCTGTG | |

| R | TGAAATCGTCGAGCAGTACG | |

| PqsE (31) | 197 | |

| F | GACATGGAGGCTTACCTGGA | |

| R | CTCAGTTCGTCGAGGGATTC | |

| RhlA (32) | 123 | |

| F | CGAAAGTCTGTTGGTATCGG | |

| R | CGTCCTTGGTGATCAACCC | |

| LasB (33) | 142 | |

| F | CTGGTTGAAGGAGGGATCAG | |

| R | GTCGTAGTGCTTGTGGGTGA |

3.9. Experimental Groups and Bacterial Preparation

Thirty healthy 6-week-old female C57BL/6J (specific pathogen-free grade) were acclimatized for 3 days and randomly divided into three groups (n = 10/group): (1) control group, (2) PA312-infected group, and (3) FOM-treated infected group. The clinical PA312 strain was cultured on Columbia blood agar at 37°C for 24h, then inoculated into LB broth and incubated overnight (180 rpm, 37°C). Bacterial suspensions were adjusted to 1.0 × 108 CFU/mL using sterile saline (McFarland standard).

3.10. Establishment of Pulmonary Infection Model

Mice were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate (3 mL/kg, i.p.) and subjected to intratracheal inoculation. Using transoral illumination and microsurgical techniques, an intravenous catheter was inserted into the trachea under direct visualization of the glottis. Successful intubation was confirmed by respiratory fluctuation of the bacterial suspension in the catheter. Fifty μL of PA312 suspension (or sterile saline for controls) were slowly instilled, followed by positional rotation to ensure bilateral pulmonary distribution.

3.11. Fosfomycin Treatment in a Murine Pulmonary Infection Model

To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of FOM, a well-established murine pulmonary infection model was employed. Sample size was estimated a priori using a log-rank (Schoenfeld) approximation with two-sided α = 0.05 and 1 - β = 0.80, assuming day-4 survival of ~60% in controls versus ≥ 90% with FOM (hazard ratio ≈ 0.20 - 0.30). The calculation yielded n ≈ 9 per group; n = 10/group was used to accommodate potential attrition.

Rationale for dosing. FOM was administered 160 mg/kg SC every 12 h. In mice, FOM shows a short SC plasma half-life (~ 0.5 - 1.1 h), and efficacy correlates with the AUC/MIC index; repeated dosing therefore maintains exposure windows during the study period. The selected regimen lies within commonly used murine ranges (≈ 200 - 500 mg/kg with q8 - q12h schedules) and was intended to sustain sub-MIC lung exposure for QS modulation rather than bactericidal sterilization (34). Thirty minutes after bacterial inoculation, mice in the FOM-treated group (n = 10) received a subcutaneous injection of 100 μL FOM (160 mg/kg body weight). Control groups received an equivalent volume (100 μL) of PBS administered subcutaneously. Treatments were administered every 12 hours to maintain therapeutic drug levels.

3.12. Measurement of Inflammatory Cytokines in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid

Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation under anesthesia. The trachea was cannulated with an angiocatheter, and lungs were lavaged three times with 0.8 mL ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was centrifuged (4°C, 500 × g, 10 min), and supernatants were stored at -80°C until analysis. Concentrations of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, CXCL1, IL-10 were quantified using ELISA kits (manufacturer name, catalog number) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

3.13. Histopathological Analysis (Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining)

Lung tissues were collected after euthanasia, fixed in 10% formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 - 5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) following standard protocol: deparaffinization in xylene, rehydration through graded alcohols, hematoxylin staining (5 min), eosin counterstaining (1 - 3 min), and mounting with neutral balsam. Tissue morphology was examined using an Olympus BX53 microscope to assess inflammatory infiltration and alveolar damage.

3.14. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 17.0 software (IBM Corp.), with continuous variables expressed as mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ± SD). Prior to parametric testing, we assessed normality of residuals by Shapiro - Wilk and homogeneity of variance by Levene’s (or Brown-Forsythe for unequal sample sizes). If assumptions were met, we used two-sided Student’s t-test (two groups) or one-/two-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. When variances were unequal, Welch’s t-test/ANOVA was used. If normality was not met, we used Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post hoc, with statistical significance evaluated against the control group and denoted as *P < 0.05 (significant), **P < 0.01 (highly significant), and ***P < 0.001 (extremely significant).

4. Results

4.1. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, Growth Inhibition, and Swimming Motility Assays

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing identified 50 clinical isolates meeting the criteria for MDR-PA, designated sequentially as PA301-PA350. Agar plates with FOM concentrations ≥ 2 μg/mL showed no visible bacterial colonies compared to negative controls, indicating an MIC of 2 μg/mL for strain PAO1. Growth curve analysis (Figure 1A) revealed significant inhibition of PAO1 at 1/2 MIC (1 μg/mL) of FOM, as evidenced by delayed entry into the stationary growth phase. At 1/4 MIC (0.5 μg/mL), mild inhibition occurred, indicated by a slight delay in the onset of the logarithmic growth phase compared to the untreated control. At 1/8 MIC (0.25 μg/mL), bacterial growth closely resembled that of the control, confirming that 1/8 MIC represents a sub-inhibitory concentration suitable for subsequent experiments. Additionally, swimming motility assays (Figure 1B) showed no significant difference in colony diameter between control PAO1 and MDR-PA strains. However, under treatment with FOM at 1/8 MIC, colony diameters significantly decreased compared to untreated controls (P < 0.001), indicating that sub-inhibitory concentrations of FOM effectively inhibit the swimming motility of both PAO1 and MDR-PA strains.

4.2. Effect of Fosfomycin on Biofilm Formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

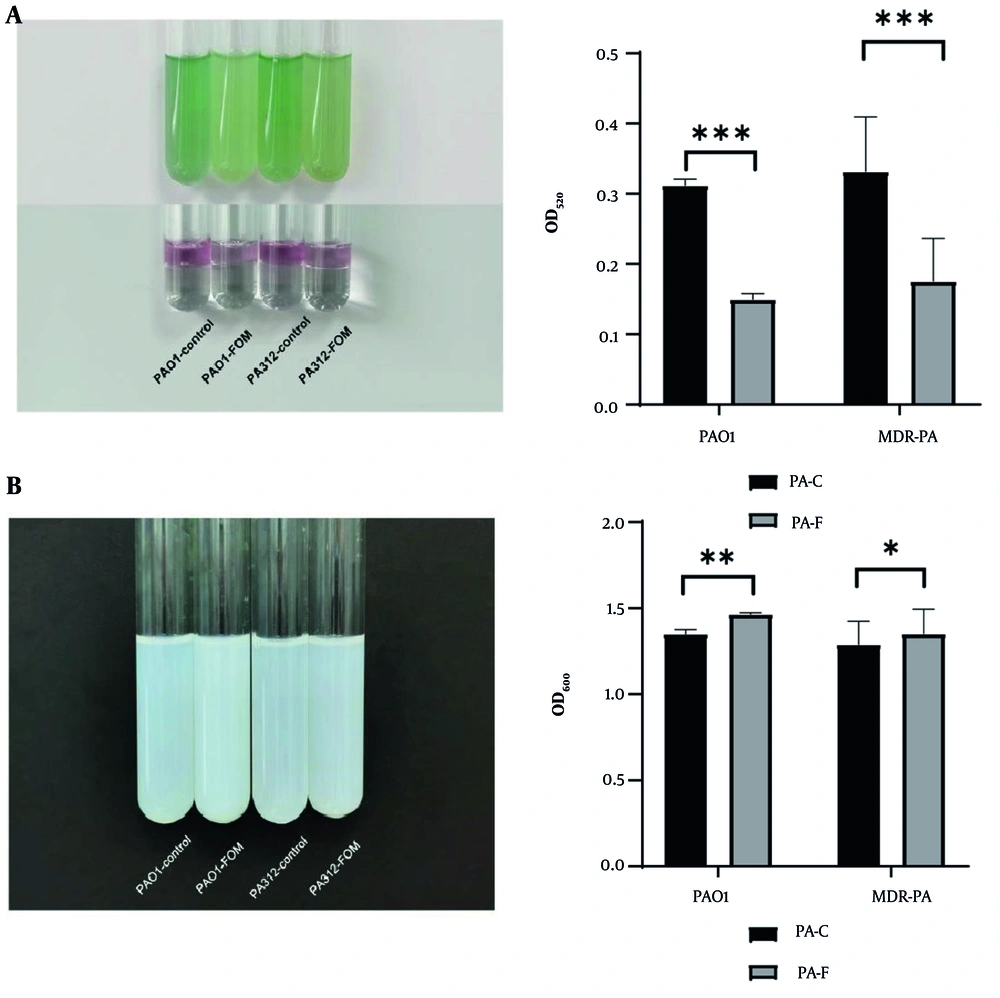

The effect of FOM at a sub-inhibitory concentration (1/8 MIC, 0.25 μg/mL) on biofilm formation was assessed by measuring absorbance (OD) of crystal violet-stained biofilms. As shown in Figure 2A, the OD values of FOM-treated groups were significantly lower compared to untreated controls (P < 0.001), demonstrating notable inhibition of biofilm formation by FOM. Furthermore, the clinical MDR-PA isolates exhibited higher mean OD values than the standard strain PAO1, indicating stronger biofilm-forming capacity. After exposure to 1/8 MIC FOM, the reduction in biofilm biomass was less pronounced in MDR-PA isolates compared with PAO1, suggesting that MDR-PA isolates are more resistant to biofilm inhibition by FOM.

Effect of sub-minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) fosfomycin (FOM) on biofilm formation and architecture. A, quantification of biofilm biomass by crystal violet staining on silicone catheter segments incubated with PAO1 or multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MDR-PA; PA312) in the presence or absence of 1/8 MIC FOM for 72 h. OD₆₀₀ values are mean ± SD (n = 3); P < 0.001 versus untreated; B, representative microscopy images (400X magnification) of crystal violet-stained biofilms on glass coverslips. Untreated controls show dense, interconnected biofilms; FOM-treated samples display sparse, fragmented biofilm patches. *** P <0.001.

Biofilm morphology was further analyzed by crystal violet staining and visualized microscopically at 400X magnification (Figure 2B). Mature, dense, and interconnected biofilms were observed in untreated control groups of PAO1 and MDR-PA strain PA312, with the latter exhibiting greater density. After treatment with 1/8 MIC FOM, biofilm production was significantly reduced in both strains (P < 0.01). PAO1 biofilms were notably disrupted, appearing as fragmented patches and clusters easily removed or destroyed. Multidrug-resistant PA biofilms (PA312) displayed decreased continuity and structural integrity, weakening their protective capacity. These results confirm that sub-inhibitory concentrations of FOM significantly impair biofilm formation and alter the structural integrity of biofilms in PA.

4.3. Effect of Fosfomycin on Pyocyanin Production and Extracellular Protease Activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

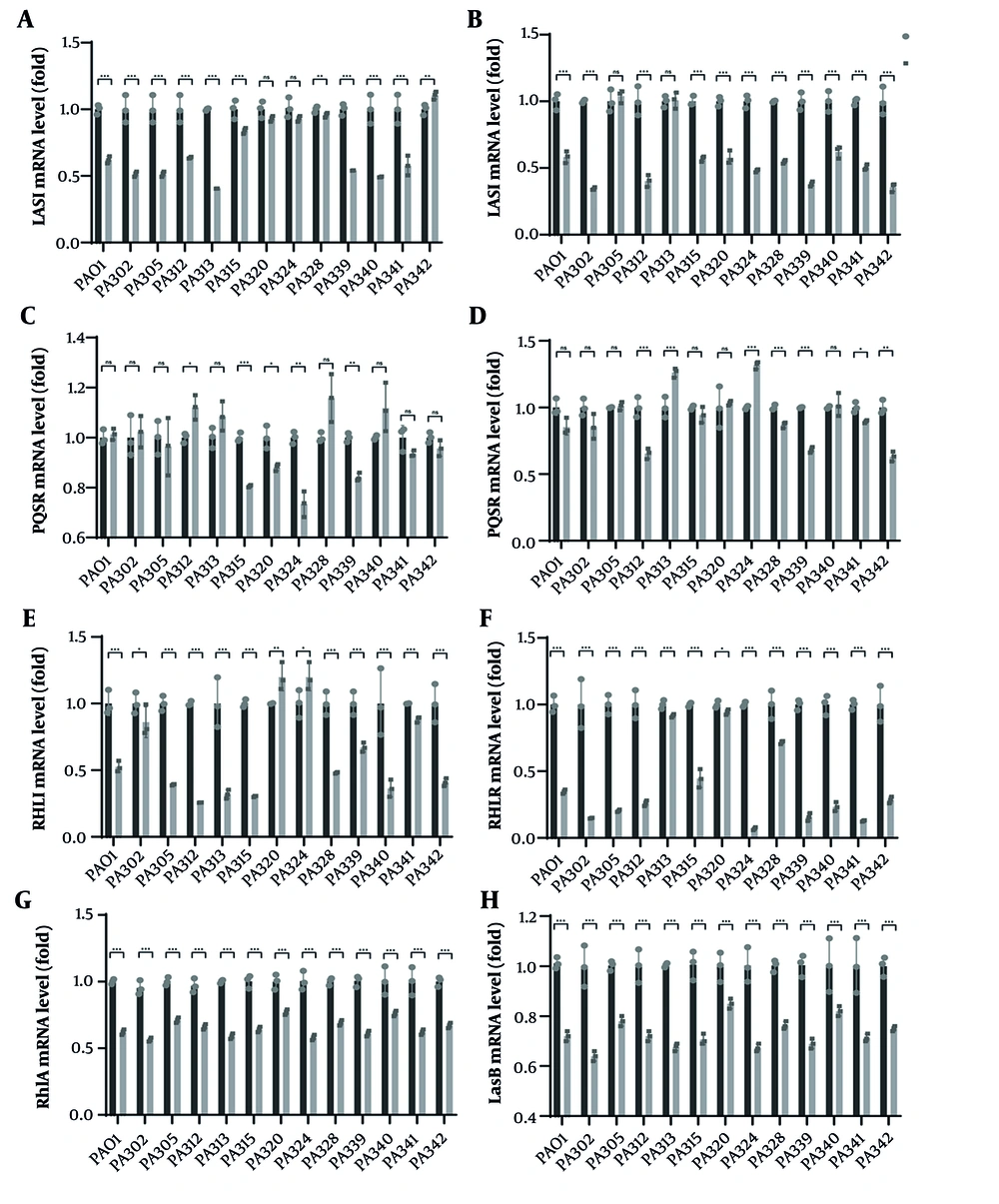

The baseline production of pyocyanin varied significantly among strains. Of the 50 MDR-PA isolates, 46 produced detectable amounts of pyocyanin, while the remaining 4 strains showed no significant difference from blank controls and were thus identified as non-pyocyanin producers. Following treatment with sub-inhibitory concentrations (1/8 MIC) of FOM, pyocyanin levels, measured by absorbance (OD), were significantly reduced in both PAO1 and MDR-PA strains compared to untreated controls (P < 0.001, Figure 3A). Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of FOM on pyocyanin production were comparable between the standard PAO1 and clinical MDR-PA isolates.

Sub-minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) fosfomycin (FOM) suppresses pyocyanin and protease production. A, pyocyanin quantification in culture supernatants of PAO1 and multidrug-resistant PA (MDR-PA) strains grown with or without 1/8 MIC FOM for 72 h. Absorbance at OD₅₂₀ reflects pyocyanin levels. FOM treatment reduced pyocyanin production (P < 0.001) (mean ± SD, n = 3); B, total extracellular protease activity measured by modified skim milk assay after 24 h incubation. Absorbance at OD₆₀₀ indicates residual milk turbidity (lower protease activity yields higher OD) (mean ± SD, n = 3). Sub-MIC FOM significantly decreased proteolysis (P < 0.05). * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

The effect of FOM on extracellular protease activity of PAO1 and clinical MDR-PA isolates was measured using a modified skim-milk assay. After incubation with 1/8 MIC FOM, bacterial supernatants were tested for protease activity by their capacity to hydrolyze skim milk proteins. Results showed significantly higher OD values in FOM-treated groups compared to untreated controls (P < 0.05, Figure 3B), indicating reduced protein degradation and thus lower extracellular protease activity. This suggests that sub-inhibitory concentrations of FOM effectively suppress extracellular protease activity in both PAO1 and MDR-PA strains.

4.4. Effect of Fosfomycin on Expression of Quorum Sensing-related Genes in Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

At 20 h under 1/8 MIC FOM, qPCR showed broad suppression of AHL-based quorum-sensing regulators across MDR-PA isolates, with PAO1 as the reference strain. In PAO1, lasI (mean 0.62) and lasR (0.58) were significantly reduced, as were rhlI (0.53) and rhlR (0.35); pqsE was unchanged (1.01) and pqsR showed a modest, non-significant decrease (0.85). Among clinical MDR-PA strains, lasI decreased in 8/13 isolates (typical means 0.41 - 0.64), while lasR decreased in 11/13 isolates (0.34 - 0.62); two strains showed no lasR change (PA305, PA313). rhlI fell in 10/13 isolates, with pronounced effects in PA312 (0.26), PA315 (0.30) and PA305 (0.39), whereas three strains were not significant (PA302, PA320, PA324). Notably, rhlR was reduced in all 13 isolates, spanning strong to modest effects (e.g., PA324 0.07, PA339 0.16, PA302 0.15; PA320 0.94). The Pqs tier was less affected: PqsE remained unchanged in most isolates (10/13), with only modest decreases in PA315 (0.81), PA324 (0.73) and PA339 (0.84). PqsR responses were heterogeneous, with significant decreases in PA312 (0.66), PA328 (0.87), PA339 (0.68) and PA342 (0.63), but increases in PA313 (1.26) and PA324 (1.32).

Overall, FOM consistently downregulated lasR/rhlR — and frequently lasI/rhlI — in both PAO1 and MDR isolates, whereas effects on pqsE and pqsR were limited or strain-dependent, indicating preferential inhibition of the AHL-based Las/Rhl tiers relative to the Pqs tier. To test whether the reduction of QS regulators translates to downstream virulence programs, we quantified two canonical targets — lasB (elastase) and rhlA (rhamnolipid) — under the same 20 h, 1/8 MIC FOM exposure (vs strain-matched control). In PAO1, lasB and rhlA fell to 0.72 ± 0.03 and 0.62 ± 0.02, respectively (both P < 0.01). Across MDR isolates, rhlA showed a median 0.64 (IQR 0.60 - 0.71; significant in 12/13 isolates) and lasB a median 0.72 (IQR 0.67 - 0.78; significant in 11/13 isolates) (Figure 4G - H). Suppression of rhlA was generally stronger than lasB (e.g., PA313 and PA339 ≈ 0.59 - 0.63 for rhlA), whereas a subset of isolates (e.g., PA320, PA340) retained relatively higher lasB expression (≈ 0.83 - 0.87), indicating expected isolate-specific heterogeneity.

Fosfomycin (FOM) downregulates quorum sensing (QS) gene expression in Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MDR-PA). Relative expression (ΔΔCt) of A, lasI; B, lasR; C, pqsE; D, pqsR; E, rhlI; F, rhlR; G, rhlA; and H, LasB in MDR-PA strains cultured 20 h with 1/8 MIC FOM (PA-F) versus untreated control (PA-C, set to 1). Data are mean ± SD (n = 3); * P < 0.01; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Notably, these transcriptional decreases paralleled the functional readouts — reduced pyocyanin and total protease activity (Figure 3A - B), and diminished motility/biofilm biomass (Figure 1, Figure 2A - B) — supporting an AHL-tier-biased antivirulence effect of FOM that extends from regulator-level changes (Figure 4A - F) to downstream virulence genes (Figure 4G - H). To strengthen the QS specificity of our observations, we included a positive control (AZM, 2 µg/mL, 20 h) with matched Vehicle in PAO1 and two MDR isolates (PA312, PA324). AZM produced stronger down-regulation of the AHL-based tiers, with fold-changes (mean ± SD, vs. Vehicle) in PAO1 of lasR 0.48 ± 0.06, lasI 0.55 ± 0.07, rhlR 0.40 ± 0.05, rhlI 0.45 ± 0.06, and modest effects on Pqs (pqsR 0.78 ± 0.08; pqsE 0.88 ± 0.09). Similar patterns were observed in PA312 (lasR 0.52 ± 0.07; rhlR 0.43 ± 0.06) and PA324 (lasR 0.46 ± 0.06; rhlR 0.38 ± 0.05) (Figure S1C in Supplementary File). These controls corroborate the direction of FOM’s effects and support an antivirulence mechanism acting primarily through Las/Rhl suppression.

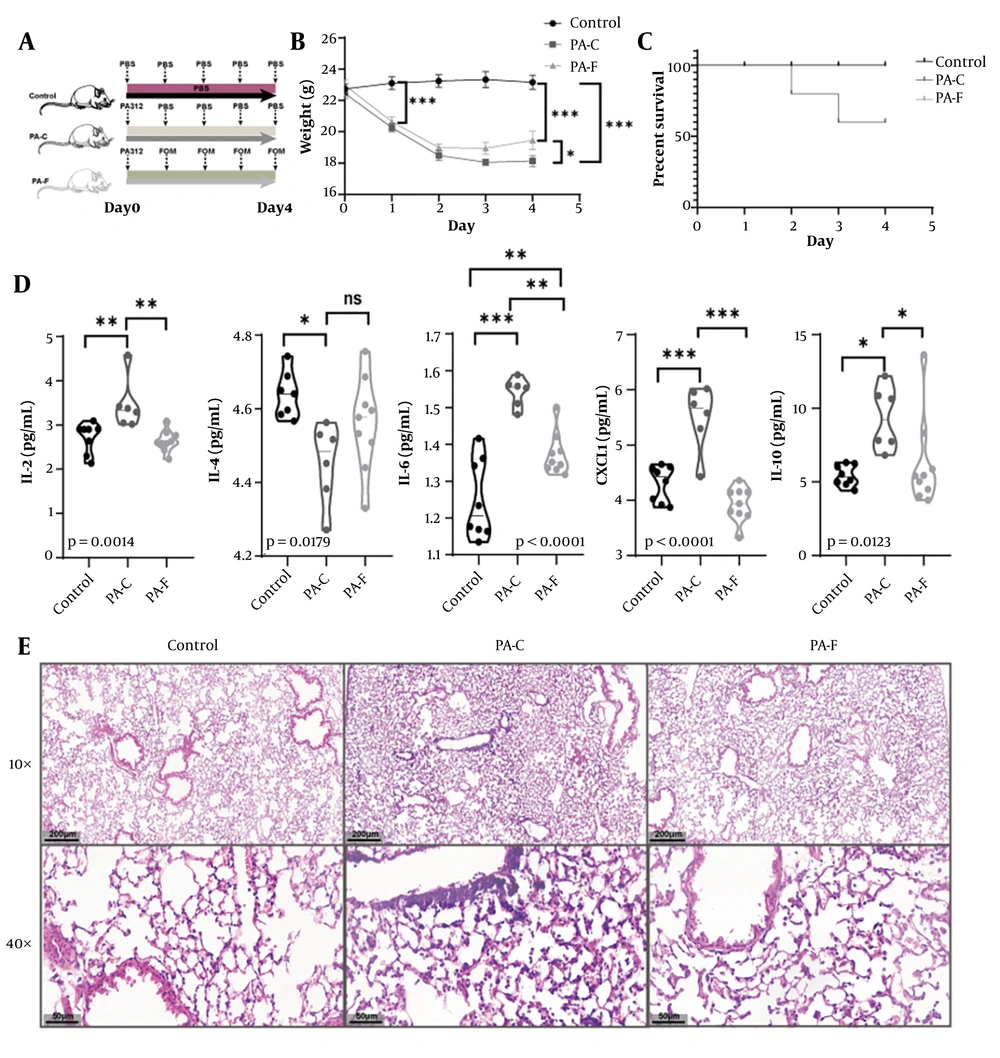

4.5. Fosfomycin Ameliorates Weight Loss, Improves Survival, and Attenuates Pulmonary Inflammation in a Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa 312-Induced Acute Lung Injury Model

To evaluate the in vivo efficacy of FOM, C57BL/6 mice were intratracheally infected with MDR-PA312 (PA-C), then either left untreated or treated with FOM (PA-F); uninfected mice served as controls (Figure 5A). PA-C mice lost significant body weight from day 1 to day 4 (P < 0.001 vs. control), whereas PA-F mice exhibited significantly less weight loss and partial recovery by day 4 (P < 0.05 vs. PA-C) (Figure 5B). Survival at day 4 was 100% in controls and PA-F, ~60% in PA-C (Figure 5C). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from PA-C mice showed marked elevations of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, CXCL1, and IL-10 versus control (all P < 0.01). FOM treatment significantly reduced IL-2 and IL-4 (P < 0.01), IL-6 and CXCL1 (P < 0.001), and IL-10 (P < 0.05) compared to PA-C (Figure 5D). Lung sections from PA-C mice displayed thickened alveolar septa, interstitial edema, and dense neutrophilic infiltration. In PA-F mice, alveolar architecture was largely preserved, with thinner septa and reduced inflammatory infiltrates (Figure 5E). Consistent with the in vitro pattern, lung-derived bacterial qPCR (Figure S1D found in Supplemetary File) showed modest but consistent attenuation of the AHL tier (las/rhl) under sub-MIC FOM, with limited and strain-dependent effects on the Pqs tier, supporting QS modulation in vivo.

Fosfomycin (FOM) protects mice from Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MDR-PA)-induced acute lung injury (ALI). A, experimental timeline: Intratracheal inoculation with PA312, followed 30 min later by subcutaneous FOM (160 mg/kg) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), administered every 12 h; B, body weight change over 4 days post-infection. PA-FOM (PA-F, FOM-treated) mice lost significantly less weight than untreated PA-control (PA-C) mice (P < 0.05) (mean ± SD); C, Kaplan-Meier survival curves over 4 days (n = 10 per group). Survival was 100 % in control and PA-F groups versus ~60% in PA-C (P < 0.01); D, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) cytokine levels (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, CXCL1, IL-10) measured by ELISA on day 4. Fosfomycin treatment significantly reduced all cytokines compared to PA-C (P < 0.05 to P < 0.001; mean ± SD); E, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung sections (4 μm) at 10X and 40X magnification. * P <0.05; ** P <0.01; *** P < 0.001.

5. Discussion

The primary components of the PA biofilm matrix include exopolysaccharides (EPS), extracellular DNA (eDNA), and matrix proteins, all of which play essential roles in structural integrity and antimicrobial resistance. Pseudomonas aeruginosa produces three major EPS: alginate, Pel, and Psl (35). Alginate, a copolymer of α-L-guluronic acid and β-D-mannuronic acid linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bond (36), is overproduced in mucoid biofilms, enhancing resistance to antibiotics and host immune defenses (37). Psl, encoded by the pslA-O operon, mediates cell-surface adhesion and biofilm structural integrity (38). Pel, a cationic EPS composed of acetylated N-acetylgalactosamine and N-acetylglucosamine polymers (39), is critical for biofilm formation at air-liquid interfaces (40). Both Pel and Psl serve as key structural polysaccharides in non-mucoid and mucoid biofilms (41). Biofilms function as physical barriers that impede antibiotic diffusion into bacterial cells while simultaneously enhancing PA's resistance to environmental stressors and promoting host colonization (42, 43).

Quorum sensing is essential for PA pathogenesis, regulating processes from initial host colonization to invasion, systemic dissemination, immune evasion, and antibiotic resistance. The QS systems in PA work together in a coordinated way. The Las system uses OdDHL as its signal molecule. When OdDHL binds to LasR, it forms active complexes that turn on several genes including rhlR, rhlI, lasI, and other virulence genes (44-46). At the same time, the Rhl system has its own activation loop. The RhlR-BHL complex can stimulate expression of both its target genes and the RhlI synthase (44). The Las system holds a pivotal position in QS of PA. While QS inhibition has been reported for other antibiotic classes, our study provides, to our knowledge, the first comprehensive evidence that sub-inhibitory FOM directly and concurrently modulates the core Las, Rhl, and Pqs circuits in PA. Our experiments demonstrated that FOM significantly downregulated LasR/LasI gene expression (Figure 4), reducing the production of autoinducer synthases and receptor proteins. This inhibition disrupts the positive feedback loop and partially suppresses LasA/LasB protease synthesis. Consequently, these effects impair initial biofilm adhesion, matrix formation, and bacterial virulence.

In addition, in this study, FOM treatment significantly downregulated RhlR/RhlI gene expression in the Rhl system, with a more pronounced effect compared to the Las system, leading to greater suppression of virulence factors such as pyocyanin and rhamnolipids. Notably, since both Las and Rhl systems utilize AHL derivatives as autoinducers (AIs) (47), the observed inhibition suggests that FOM may structurally mimic AHLs, competitively blocking autoinducer-receptor binding and disrupting the autoinduction feedback loop. This mechanism aligns with previous reports of QS inhibition by aminoglycosides and NSAIDs (48, 49). However, as FOM covalently binds UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvyl transferase to inhibit peptidoglycan synthesis (50), direct suppression of LasI/RhlI synthase activity cannot be excluded.

Two non-exclusive mechanisms could underlie this transcriptional repression. First, FOM (or a metabolite) may structurally or functionally mimic AHLs, competitively blocking receptor - ligand complex formation and thereby preventing transcriptional activation (51). Similar competitive inhibition has been reported for other antibiotic classes and non-antibiotic drugs. Second, given FOM’s covalent interaction with MurA, a parallel inhibitory action on AHL synthases (LasI/RhlI) cannot be excluded (52). Resolving these possibilities will require direct quantification of AIs, enzyme activity assays, and structural docking analyses.

Fosfomycin exposure reduced biofilm biomass and visibly disrupted architecture: instead of dense, reticulated structures, we observed sparse, patchy films and scattered bacterial clusters (Figure 2). These phenotypes align with reduced expression of Las/Rhl regulators, which control flagella/pili genes, EPS components (alginate, rhamnolipids), and biofilm-associated enzymes. The concurrent inhibition of swimming motility further supports impaired pili/flagellar function, limiting surface colonization and microcolony consolidation (Figure 4B). Pyocyanin, regulated largely by Rhl and Pqs, is a key phenazine that induces oxidative stress, disrupts mitochondrial electron transport, impairs ciliary function, and kills immune cells (53). Its marked reduction under FOM treatment dovetails with the significant repression of rhlR/rhlI. Extracellular proteases, including LasA/LasB and alkaline protease, promote tissue damage, nutrient acquisition, and biofilm maintenance. We observed a modest but significant decrease in total protease activity, matching the direction of change in Las and Rhl expression (Figure 3B).

Most importantly, we demonstrate for the first time that the QS-inhibitory activity of sub-MIC FOM translates to significant therapeutic efficacy in a mammalian infection model. In our murine model of MDR-PA312-induced acute lung injury (ALI), FOM demonstrated significant therapeutic efficacy by mitigating weight loss, improving survival, and attenuating pulmonary inflammation. The observed preservation of lung architecture and reduction in proinflammatory cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, CXCL1, and IL-10) in FOM-treated mice align with its known antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties. A hallmark feature of lung injury is the upregulation of proinflammatory mediators, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukins (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, CXCL1, and IL-10) (54, 55). IL-4 exhibits dual roles in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, suppressing early T cell-mediated inflammation (reducing TNF-α, IFN-γ, and NO) while promoting late-stage fibrotic responses (56). In this PA-induced model, IL-4 primarily demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects (Figure 5D).

Our data indicate QS modulation at sub-MIC exposure but do not establish direct AHL-receptor antagonism or synthase inhibition. The notion that FOM might mimic AHLs or directly interfere with LasR/RhlR or LasI/RhlI should therefore be regarded as a hypothesis. In keeping with this more conservative interpretation, we added lung-derived transcript data (Figure S1D, in Supplementary File) that corroborate in vivo attenuation of AHL-tier signaling while Pqs effects remain limited/variable; definitive tests of receptor binding, autoinducer levels, and synthase activity are required.

These findings gain further mechanistic context when considered alongside recent advances in ALI pathogenesis. For instance, PAI-1 deficiency exacerbates PA-induced ALI by enhancing neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation and thromboinflammation via PI3K/MAPK/AKT activation, suggesting that FOM’s protective effects may extend beyond direct bacterial killing to modulation of NETosis or thromboinflammatory pathways (57). Similarly, the CLEC5A-LPS interaction drives PA-induced NET formation and lung injury, and its blockade synergizes with antibiotics like ciprofloxacin to improve outcomes. While FOM’s impact on CLEC5A signaling remains unexplored, our data — combined with these reports — highlight the potential of multitargeted therapies combining antimicrobial and host-directed strategies. Notably, the patatin-like phospholipase domain of ExoU toxin is essential for PA virulence, and its inactivation abolishes lung injury (58). Although our MDR-PA312 strain’s virulence factors were not characterized, FOM’s efficacy against this strain suggests it may indirectly mitigate toxin-mediated damage through bacterial load reduction or immunomodulation.

Collectively, these findings position FOM as a promising candidate for MDR-PA pneumonia, warranting further investigation into its interplay with NETosis, thromboinflammation, and toxin neutralization pathways. A schematic model summarizing the proposed mechanism of sub-MIC FOM-mediated quorum-sensing modulation is illustrated in Figure 6, highlighting its attenuation of the Las/Rhl/Pqs circuits and downstream virulence phenotypes leading to protection against MDR-PA-induced lung injury.

Proposed model of Fosfomycin (FOM)-mediated QS modulation. At sub-minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) exposure, FOM modestly down-regulates Las/Rhl signaling (solid downward arrows) with limited/strain-dependent effects on Pqs, leading to reduced rhlA/lasB expression and attenuation of motility, biofilm, pyocyanin, and extracellular protease, and to improved lung outcomes. Dashed arrows indicate hypothesized, unverified mechanisms [e.g., acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL)-receptor mimicry or direct effects on LasI/RhlI]. This schematic reflects a quorum sensing (QS)-modulating adjuvant concept rather than stand-alone QS blockade.

5.1. Conclusions

These outcomes likely reflect the combined effect of partial antibacterial activity and attenuation of QS-controlled virulence, reducing tissue damage and inflammatory burden. Clinically, these data argue for repurposing FOM as an adjuvant to standard-of-care antibiotics, even when MIC testing suggests modest susceptibility. By weakening virulence and biofilm barriers, FOM could potentiate partner drugs, shorten therapy, and reduce relapse. Importantly, FOM’s distinct mechanism and low cross-resistance profile make it attractive in stewardship programs focused on minimizing resistance amplification.

Future investigations should focus on elucidating FOM's molecular mechanism by quantifying AHLs/PQS levels, assessing LasI/RhlI enzymatic activity, and conducting binding studies to validate competitive inhibition hypotheses. Systems-level profiling through transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics could reveal global QS network perturbations, including effects on the Iqs subsystem. Genomic sequencing of atypical isolates may identify mutations in phz loci, EPS pathways, or resistance determinants. Combination therapies with β-lactams, colistin, or carbapenems should be tested for synergistic anti-biofilm efficacy against MDR-PA, with optimization of dosing regimens. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling must determine whether clinically achievable lung concentrations maintain sub-MIC QS inhibition without resistance selection. Finally, translational studies in clinically relevant models (e.g., ventilator-associated pneumonia) should evaluate bacterial clearance, inflammation resolution, and relapse rates to bridge mechanistic insights to therapeutic outcomes.

![Proposed model of Fosfomycin (FOM)-mediated QS modulation. At sub-minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) exposure, FOM modestly down-regulates Las/Rhl signaling (solid downward arrows) with limited/strain-dependent effects on Pqs, leading to reduced rhlA/lasB expression and attenuation of motility, biofilm, pyocyanin, and extracellular protease, and to improved lung outcomes. Dashed arrows indicate hypothesized, unverified mechanisms [e.g., acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL)-receptor mimicry or direct effects on LasI/RhlI]. This schematic reflects a quorum sensing (QS)-modulating adjuvant concept rather than stand-alone QS blockade. Proposed model of Fosfomycin (FOM)-mediated QS modulation. At sub-minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) exposure, FOM modestly down-regulates Las/Rhl signaling (solid downward arrows) with limited/strain-dependent effects on Pqs, leading to reduced rhlA/lasB expression and attenuation of motility, biofilm, pyocyanin, and extracellular protease, and to improved lung outcomes. Dashed arrows indicate hypothesized, unverified mechanisms [e.g., acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL)-receptor mimicry or direct effects on LasI/RhlI]. This schematic reflects a quorum sensing (QS)-modulating adjuvant concept rather than stand-alone QS blockade.](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/b97c3a3c8ee1c088c7d4bdd11facddc4b27a045e/jjm-19-1-166214-i006-preview.webp)