1. Background

Bacteriophages are viruses that specifically infect bacteria and are now considered a novel and promising approach for treating bacterial infections, particularly strains resistant to conventional therapies. Due to their high specificity and bactericidal capability, they are regarded as suitable natural biocontrol agents in various fields, including food safety and preservation. The rise of bacterial resistance has limited the use of standard antimicrobial treatments, and at the same time, contamination of dairy products with multidrug-resistant bacteria, such as Pseudomonas spp., causes significant problems, leading to product spoilage and financial losses (1, 2). When Pseudomonas spp., which are naturally resistant and spoilage-causing, contaminate dairy products, alternative microbial control methods become necessary.

Bacteriophages can specifically target and destroy these bacteria without affecting the beneficial microbiota or altering the taste and quality of the products. Recent studies have shown that lytic bacteriophages can effectively target harmful and spoilage-causing bacteria in milk and cheese, highlighting their potential to improve food safety and extend product shelf life (3, 4). Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages from environments related to dairy production, such as water and equipment reservoirs, provide important insights into their morphology, host range, and stability under different pH and temperature conditions. Detailed phenotypic and molecular analyses, including transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and growth rate assessments, help in selecting effective bacteriophages for therapeutic or biocontrol cocktails. These cocktails can expand the spectrum of activity, prevent the development of bacterial resistance, and position bacteriophages as a reliable alternative or efficient complement to antibiotics in dairy microbiology (5, 6).

Bacteriophage treatment is a promising approach in light of the pressing need for efficient interventions against multidrug-resistant bacteria in food systems. Its use in dairy products satisfies consumer demands for less chemical use and natural preservation. The incorporation of bacteriophage-based solutions into dairy industry operations will be supported by ongoing research on bacteriophage-host interactions, efficacy in dairy matrices, and possible regulatory acceptability, improving public health and product quality (1, 7).

2. Objectives

Ongoing research on bacteriophage-host interactions, their efficacy in dairy products, and potential regulatory acceptance supports the effective integration of bacteriophage-based solutions into the dairy industry, enhancing both public health and product quality.

3. Methods

3.1. Isolation, Identification, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

A total of 100 samples of livestock-derived products (milk and cream) were aseptically collected in sterile containers, stored at 4°C, and transported to the Microbiology Laboratory at Ayatollah Amoli Branch University. For bacterial enrichment, 10 mL of each sample was added to 90 mL of tryptic soy broth (TSB; Merck, Germany) and incubated at 30°C for 24 hours. Following enrichment, 100 µL of the culture was streaked on cetrimide agar (HiMedia, India) and incubated at 30°C for 24 - 48 hours to isolate Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8, 9). Colonies were identified using standard biochemical tests and the Microbact 12E rapid detection system (Oxoid, UK) for gram-negative bacteria. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PTCC1430 was obtained from IROST for bacteriophage-related studies. Antibiotic resistance was evaluated using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method according to CLSI M100 guidelines (10).

3.2. PCR Amplification and Phylogenetic Identification of Pseudomonas spp

Genomic DNA from selected Pseudomonas spp. isolates was extracted using the standard boiling method for bacterial DNA preparation (11). The 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using universal bacterial primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (12). The PCR reaction mixture (25 µL) contained 12.5 µL of 2× PCR master mix, 1 µL of each primer (10 µM), 2 µL of template DNA, and 8.5 µL of nuclease-free water. Thermal cycling was performed in a PCR thermocycler under the following conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 60 s, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min (13). PCR products were verified by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel containing SYBR Safe and visualized under a UV transilluminator.

The final 16S rRNA sequences obtained from Pseudomonas spp. using an ABI 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA) were quality-checked, and species identification was confirmed by comparing them with sequences available in the NCBI database using the BLASTn tool. Sequences were aligned using MUSCLE in Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms (MEGA X), and phylogenetic trees were constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates to confirm the identity and clarify the evolutionary relationships among Pseudomonas spp. The resulting trees provided insights into strain clustering and genetic relatedness, supporting accurate classification of the isolates (14).

3.3. Bacteriophage Isolation and Purification

Ten water samples were collected from air conditioning reservoirs and sediment at the Children's Hospital in Amirkola city, Mazandaran province. Samples were stored at 4°C and transported to the laboratory under chilled conditions. Upon arrival, samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove contaminants. The supernatants were filtered through 0.45 μm syringe filters. Subsequently, 10 mL of the filtered supernatant was mixed with 5 mL of the Pseudomonas spp. culture in the logarithmic growth phase and 10 mL of TSB. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 24 hours with shaking at 180 rpm. After incubation, the enriched solution was filtered again and subjected to double-layer agar plaque assays (6, 15). Individual plaques were isolated and purified, and the purified bacteriophages were stored at 4°C.

3.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy

Ten microliters of purified bacteriophage [~108 plaque-forming unit (PFU)/mL] were placed on a copper grid and dried at room temperature for 5 minutes. The grid was stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid for 2 minutes and observed using a Hitachi H-7000FA transmission electron microscope (16).

3.5. Lytic Activity of the Isolated Bacteriophage

Lytic activity was initially evaluated using a spot assay on bacterial lawns. Further quantitative analysis was performed in 96-well microtiter plates. Host range and efficiency of plating (EoP) were assessed to determine the spectrum of activity (17, 18).

3.6. One-Step Growth Curve Assay

Ten milliliters of mid-log phase Pseudomonas spp. cultures were mixed with bacteriophages (~108 PFU/mL) at the optimal multiplicity of infection (MOI) and incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes. The mixtures were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 minute, and the resulting pellets were resuspended in 10 mL of TSB and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 160 rpm. Samples were collected at 10-minute intervals for 1 hour to determine bacteriophage titers by PFU counts (6). The burst size was calculated by dividing the total number of bacteriophages released by the number of initially infected bacterial cells, indicating how many bacteriophages each infected cell produced on average (19).

3.7. Determination of Multiplicity of Infection

A bacterial culture [108 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL] was infected with bacteriophage suspensions at concentrations of 105 - 108 PFU/mL. After 6 hours incubation at 37°C, bacterial growth was measured via OD600nm (20).

3.8. Thermal and pH Stability of Bacteriophages

Bacteriophages (Phps1, Phps2, Phps4) were tested across pH 4 - 12 (optimal at pH 7). Activity declined at pH ≤ 3 or ≥ 13. Thermal stability was tested at 30°C to 80°C for 30 and 60 minutes. No viable bacteriophages were detected above 70°C. The remaining bacteria were checked by double-layer agar plaque assays (21).

3.9. Phage Cocktail Preparation and Evaluation of Lytic Activity

A 1:1 mixture of isolated bacteriophages was prepared at 9 log10 PFU/mL in SM buffer. For testing, 10 µL of bacterial culture was spread on Luria-Bertani Agar (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., India), followed by 10 µL of the phage cocktail. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours to assess plaque formation (5).

3.10. Bacteriophage Efficacy Against Pseudomonas spp. in Pasteurized Milk

Five milliliters of pasteurized milk were transferred into sterile 15 mL Falcon tubes. Then, 100 μL of Pseudomonas spp. suspension (105 CFU/mL) was added and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes to allow bacterial adaptation. Next, 100 μL of bacteriophage lysate (108 PFU/mL) was added to the test tubes. Two control groups were included: A positive control (milk with bacteria, no bacteriophage) and a negative control (milk with sterile SM buffer, no bacteria or bacteriophage). All samples were incubated at both 4°C and 25°C and bacterial counts were determined at 0, 3, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours by plating on appropriate culture media (22, 23).

3.11. Application of Phage Cocktail in Whole Milk

To evaluate the efficacy of a phage cocktail against a mixed Pseudomonas spp. culture in pasteurized milk, a controlled experiment was conducted. The bacterial mixture was prepared by combining equal volumes of cultures of Pseudomonas strains PSM01 and PSC05, adjusted so that each strain had an equal final concentration in the mixture. The phage cocktail was similarly prepared by mixing two lytic bacteriophages, Phps1 and Phps4, to a final titer of 10⁸ PFU/mL. Pasteurized milk was used as the model food matrix for this assay. Three experimental groups were included in the study.

In the treatment group, 5 mL of the bacterial mixture was added to 40 mL of milk and held briefly at room temperature, after which 5 mL of the phage cocktail was added. In the positive control group, 5 mL of the bacterial suspension was mixed with 5 mL of sterile medium and added to 40 mL of milk. For the negative control, 10 mL of sterile medium was added to 40 mL of milk without any bacteria (24). All samples were incubated at both 4°C and 25°C for a total duration of 96 hours. Sampling was carried out at 0, 3, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. At each time point, serial dilutions were prepared, and 100 µL of each dilution was plated onto tryptic soy agar (TSA). After incubation at 36°C, CFUs were counted to determine bacterial viability over time.

3.12. Statistical Analysis

All experiments related to the lytic activity of bacteriophages (Phps1, Phps2, Phps3, Phps4, Phps04, and Phps01 against six different Pseudomonas spp.) were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The diameters of the clear zones (in mm) produced by each bacteriophage against different Pseudomonas strains were measured and used for statistical comparison. Data normality and homogeneity of variances were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences among mean lysis zone diameters across bacteriophages and host strains were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test for pairwise comparisons when significant differences were observed. Additionally, the relationship between bacteriophage host range and mean lysis zone diameter was evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Isolation and Resistance Patterns of Pseudomonas spp. from Dairy Products

The bacterial strains isolated from food samples included PSM04 and PSM01 from milk, and PSC05, PSC3, and PSC06 from cream. Most isolates showed high or complete resistance to ampicillin, cefixime, and sulfamethoxazole. Resistance to meropenem and amikacin varied; notably, only P. aeruginosa PTCC 1430 was sensitive to meropenem. Gentamicin exhibited moderate to strong efficacy against most isolates (Table 1). Table 1 summarizes the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of six Pseudomonas strains (PSC3, PSM04, PSM01, PSC05, PSC06, and PTCC 1430) against seven antibiotics, as determined by the standard disk diffusion method.

| Strains | Sources | Meropenem (mm) | Gentamicin (mm) | Amikacin (mm) | Cefixime (mm) | Sulfamethoxazole(mm) | Ceftazidime (mm) | Ampicillin (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSC3 | Cream | 10 (R) | 22 (S) | 20 (S) | 12 (R) | 16 (I) | 24 (S) | 10 (R) |

| PSM04 | Milk | 24 (S) | 20 (S) | 12 (R) | 10 (R) | 11 (R) | 13 (R) | 9 (R) |

| PSM01 | Milk | 10 (R) | 21 (S) | 11 (R) | 13 (R) | 16 (I) | 23 (S) | 10 (R) |

| PSC05 | Cream | 9 (R) | 12 (R) | 16 (I) | 11 (R) | 10 (R) | 17 (I) | 10 (R) |

| PSC06 | Cream | 8 (R) | 17 (I) | 10 (R) | 9 (R) | 11 (R) | 21 (S) | 9 (R) |

| PTCC 1430 | Reference strain | 18 (I) | 18 (I) | 11 (R) | 12 (R) | 16 (I) | 14 (R) | 10 (R) |

a The results indicate each strain’s level of resistance, sensitivity, or intermediate response to the tested antibiotics, providing insight into their antimicrobial resistance profiles.

b Legend: R = Resistant, S = Sensitive, and I = Intermediate.

4.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Phylogenetic Analysis

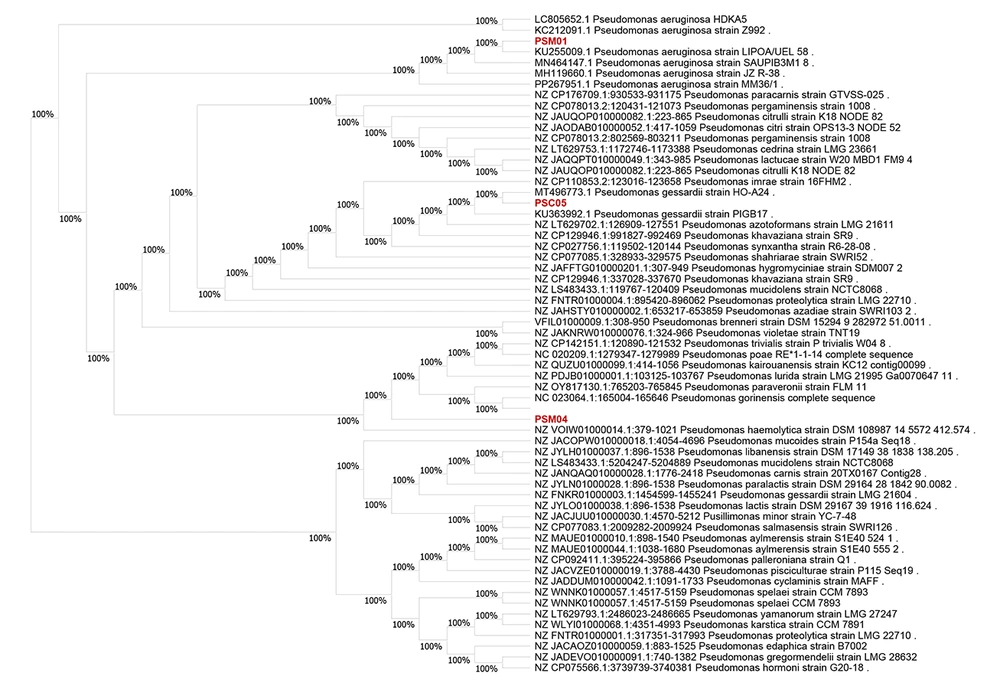

Among the five isolates, three were selected for 16S rRNA gene sequencing based on their colony morphology and antimicrobial activity. Phylogenetic analysis of the sequencing results revealed the evolutionary relationships between the bacterial isolates PSM01, PSM04, and PSC05 and the reference Pseudomonas spp. Isolate PSM01 showed the highest similarity to P. aeruginosa strain LIPOA/UEL 58 (GenBank accession no. KU255009.1). Isolate PSC05 was most closely related to P.gessardii strain PIGB17 (GenBank accession no. KU363992.1), while PSM04 clustered with P.gorinensis strain DSM 108987 (GenBank accession no. NZ_VOIW01000014.1, positions 379-1021). All reference sequences were retrieved from the NCBI database. The 16S rRNA sequences were submitted to the NCBI GenBank database and assigned the following accession numbers: PV759807 for PSM01, PV759808 for PSC05, and PV759809 for PSM04 (Figure 1).

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the evolutionary relationships of bacterial isolates PSM01, PSM04, and PSC05 with reference Pseudomonas species: The tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method; isolate PSM01 clustered with Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain LIPOA/UEL 58 (KU255009.1); PSC05 grouped closely with P.gessardii strain PIGB17 (KU363992.1), and PSM04 was related to P.gorinensis strain DSM 108987 (NZ_VOIW01000014.1:379-1021); sequences were obtained from the NCBI database. (Isolates PS03 and PS04 are highlighted in red. The scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.)

4.3. Isolation and Characterization of Bacteriophages

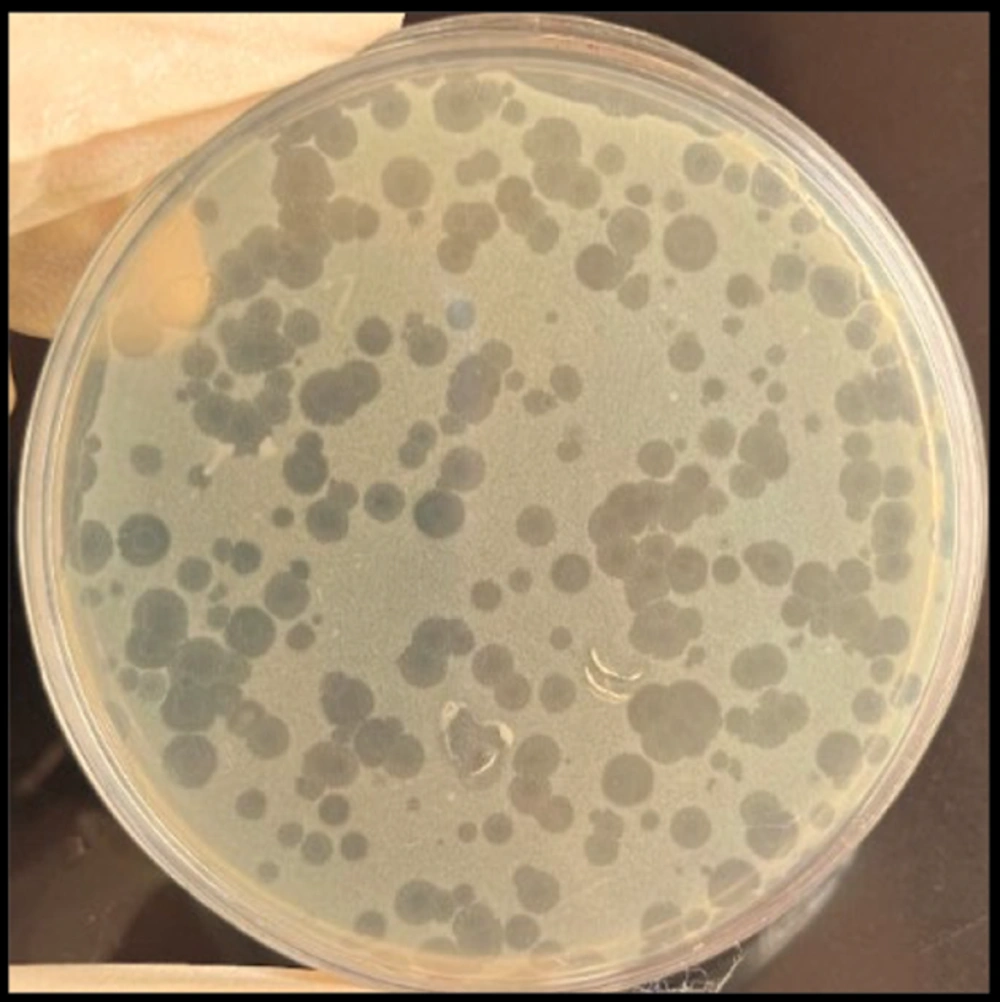

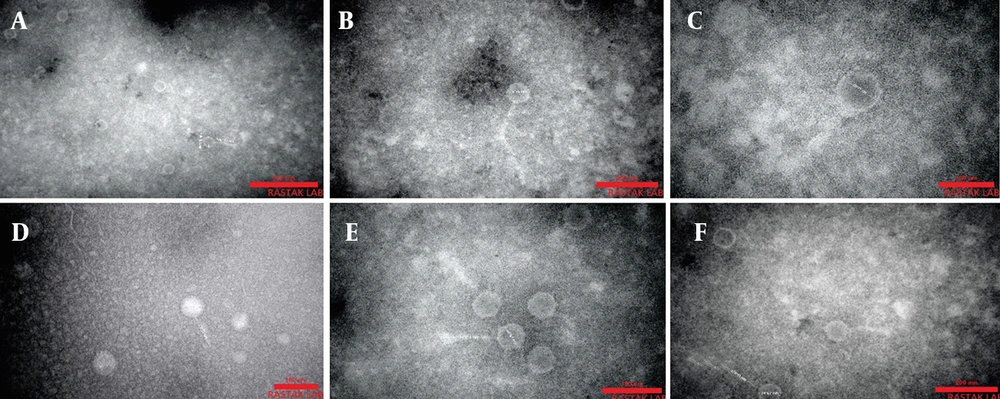

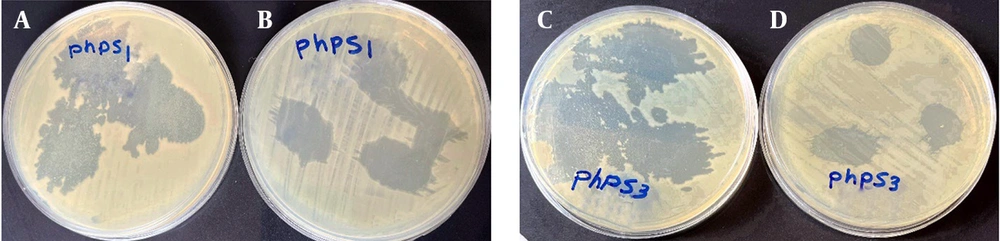

Six lytic bacteriophages targeting Pseudomonas spp. were successfully isolated from wastewater and named Phps1, Phps2, Phps3, Phps4, Phps01, and Phps04. All bacteriophages produced small, clear plaques of approximately 1 mm in diameter (Figure 2). The TEM analysis showed that these bacteriophages possessed polyhedral heads and contractile tails, features typical of the families Myoviridae and Siphoviridae. Detailed morphometric measurements of each bacteriophage are presented in Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to visualize the morphological characteristics of isolated bacteriophages (A - F). A, Phages Phps1; B, Phps2; and C, Phps3 were classified within the Myoviridae family (A - C), exhibiting icosahedral heads measuring approximately 85 × 80 nm, 76 × 72 nm, and 78 × 77 nm, respectively, and contractile tails of varying lengths (149 × 15 nm for Phps1, 304 × 13 nm for Phps2, and 175 × 36 nm for Phps3). In contrast, D, Phps4; E, Phps01; and F, Phps04 belonged to the Siphoviridae family (D - F), characterized by elongated non-contractile tails and smaller head dimensions. Specifically, Phps4 displayed a head of 55 × 51 nm with a tail of 72 × 11 nm, Phps01 had a head of 68 × 67 nm and a tail of 141 × 10 nm, while Phps04 exhibited a head of 74 × 67 nm and a tail measuring 170 × 11 nm. These structural features support the taxonomic classification and potential functional diversity of the isolated bacteriophages.

4.4. Host Range of Pseudomonas-Specific Bacteriophages

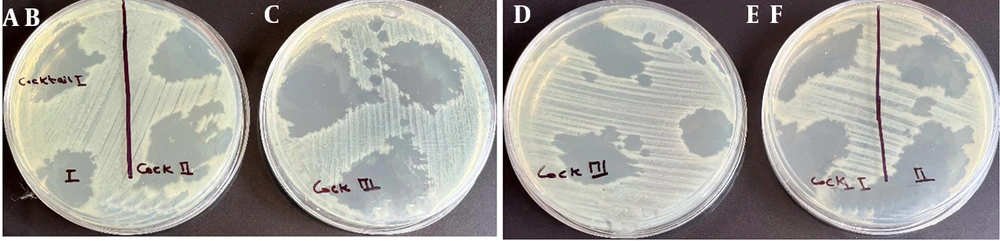

Phages Phps1, Phps3, and Phps4 demonstrated strong lytic activity against most P. aeruginosa strains (PSC3, PSM01, PSM04, PSC05, and PSC06). Phps2 and Phps04 showed narrower host ranges, and Phps01 exhibited the most limited spectrum of activity (Figure 4). To further enhance antibacterial efficacy, three different phage cocktails were tested against Pseudomonas spp. As shown in Figure 5, cocktail type 1 (Phps1, Phps2, Phps3, and Phps4) and cocktail type 2 (Phps1 and Phps4) displayed the strongest lytic activity, effectively inhibiting both PSM01 and P. aeruginosa PTCC 1430. Cocktail type 3 (Phps01 and Phps04) also showed inhibitory effects but with slightly reduced efficiency compared to the other two combinations. These results indicate that combining multiple bacteriophages can broaden the host range and enhance overall lytic potency against resistant Pseudomonas spp.

A - C, Lytic activity of three different phage cocktails against Pseudomonas strain PSM01 and; D - F, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PTCC 1430 . Panels A and E show the effect of cocktail type 1 (Phps1, Phps2, Phps3, and Phps4); panels B and F represent cocktail type 2 (Phps1 and Phps4); and panels C and D display cocktail type 3 (Phps01 and Phps04).

4.5. One-Step Growth Curve of Bacteriophages

Phps1 exhibited a short latent period (10 - 15 min) and reached a high titer (7.5 - 7.6 log PFU/mL) by minute 60. Phps2 had a longer latent phase with minimal increase until minute 20 and limited growth thereafter. Phps4 displayed intermediate performance with some titer fluctuations but remained a viable candidate for combination therapies (Appendix 1, in the Supplementary File).

4.6. Multiplicity of Infection-Dependent Efficacy of Phage Therapy

Phages Phps1, Phps2, and Phps4 were tested at multiplicities of infection of 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10. Bacterial growth inhibition increased with higher MOI. At MOI 10, Phps1 limited bacterial growth significantly, while even at MOI 0.01, a notable inhibitory effect was observed (Appendix 2, in the Supplementary File).

4.7. pH and Thermal Stability

Bacteriophages remained active across a pH range of 4 - 12, with peak activity at pH 7. Under extreme conditions (pH ≤ 3 or ≥ 13), lytic activity dropped but was not completely lost (Appendix 3, in the Supplementary File). Thermal stability tests showed highest activity at 30°C. Activity declined significantly at 60 - 80°C, especially after 60 minutes. Phps1 was the most thermally stable, while Phps4 was the least stable (Appendix 4, in the Supplementary File).

4.8. Lytic Activity of Individual Bacteriophages Against Various Pseudomonas spp

The lytic activity of six individual bacteriophages Phps1, Phps2, Phps3, Phps4, Phps04, and Phps01 was evaluated against six different Pseudomonas spp., including reference strain PTCC 1430 (Table 2).

| Host Strains | Phps1 | Phps2 | Phps3 | Phps4 | Phps04 | Phps01 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSC3 | +++ (30 mm) | +++ (23 mm) | +++ (30 mm) | +++ (22 mm) | ++ (20 mm) | ++ (21 mm) |

| PSM04 | ++ (20 mm) | + (11 mm) | ++ (21 mm) | ++ (20 mm) | + (10 mm) | ++ (20 mm) |

| PSM01 | +++ (26 mm) | +++ (22 mm) | +++ (30 mm) | +++ (32 mm) | +++ (31 mm) | +++ (30 mm) |

| PSC05 | +++ (25 mm) | +++ (28 mm) | +++ (25 mm) | +++ (23 mm) | ++ (20 mm) | ++ (19 mm) |

| PSC06 | +++ (22 mm) | ++ (18 mm) | +++ (28 mm) | ++ (19 mm) | ++ (16 mm) | + (14 mm) |

| PTCC 1430 | +++ (35 mm) | +++ (25 mm) | +++ (37 mm) | +++ (28 mm) | ++ (20 mm) | +++ (30 mm) |

a +++: Clear and translucent plaque (strong lytic activity), ++: Slightly turbid plaque (moderate lytic activity), and +: Turbid plaque (weak lytic activity).

The results demonstrated considerable variation in bacterial susceptibility and bacteriophage efficacy. Phages Phps1, Phps3, and Phps4 exhibited broad and strong lytic activity (+++) against most strains, particularly PSM01, PSC05, and the reference strain PTCC 1430. Among them, PSM01 was the most susceptible, showing strong lytic response (+++) to all tested bacteriophages. PSC05 and PTCC 1430 also showed high sensitivity to most bacteriophages. In contrast, Phps2 and Phps04 had a narrower host range. Notably, neither Phps2 nor Phps04 displayed any lytic activity (-) against the PSM04 strain. PSC06 showed variable susceptibility, with moderate to strong lysis observed only in response to Phps1 and Phps3. Phage Phps01 generally exhibited moderate (++) and, in some cases, strong (+++) lytic activity, indicating its potential for inclusion in targeted phage cocktails. However, its activity against PSC06 was weak (+), suggesting a more host-specific behavior.

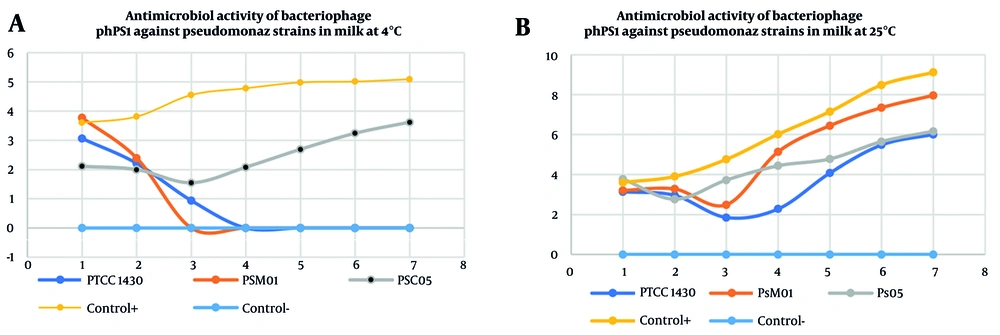

4.9. Temperature-Dependent Antibacterial Activity of Bacteriophage Phps1 in Pasteurized Milk

The antibacterial activity of bacteriophage Phps1 against three Pseudomonas strains (PSM01 and PSC05) was evaluated in pasteurized milk at two different temperatures: 4°C (Figure 6A) and 25°C (Figure 6B). At 4°C, Phps1 exhibited strong inhibitory effects, with the growth of PSM01 nearly completely suppressed by day 3. PSC05 also showed a marked reduction in bacterial count, though not total elimination. The positive control (PTCC 1430) maintained steady growth, while the negative control showed no growth as expected. In contrast, at 25°C, although an initial reduction in bacterial levels was observed for all strains, bacterial regrowth occurred after 3 - 4 days, indicating a decline in bacteriophage efficacy over time. These results suggest that lower temperatures enhance bacteriophage stability and antibacterial effectiveness, whereas higher temperatures may limit their long-term suppressive activity (Figure 6A and Figure 6B).

Antibacterial activity of bacteriophage Phps1 against Pseudomonas strains PTCC 1430 (blue), PSM01 (orange), PSC05 (gray), and the positive strain PTCC 1430 (without bacteriophage, yellow), negative control (without bacteria and bacteriophage, dark blue), in pasteurized milk A, at 4°C; and B, 25°C. At 4°C, Phps1 almost completely suppressed PSM01 and markedly reduced PSC05, while PTCC 1430 (positive control) showed steady growth. The negative control (without bacteria and bacteriophage) showed no growth as expected. At 25°C, all strains exhibited initial reduction but regrowth occurred after day 3, indicating reduced long-term efficacy at higher temperature.

4.10. Application of Phage Cocktail (Phps1 + Phps4) in Pasteurized Milk

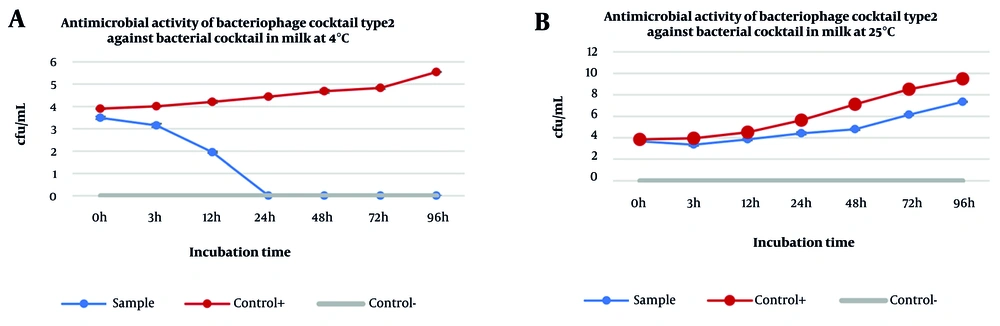

According to the results presented in Table 3, all three tested phage cocktails — type 1 (a mixture of Phps1, Phps2, Phps3, and Phps4), type 2 (Phps1 and Phps4), and type 3 (Phps01 and Phps04) — exhibited very strong lytic activity (++++) against all evaluated Pseudomonas strains (PSC3, PSM04, PSM01, PSC05, PSC06, and PTCC 1430). In addition, the antimicrobial efficacy of phage cocktail type 2 (Phps1 + Phps4) was further evaluated in pasteurized milk at two different storage temperatures (Figure 7).

| Bacterial Strains | Cocktail Phps 1 (Phps1 + Phps2 + Phps3 + Phps4) | Cocktail Phps 2 (Phps1 + Phps4) | Cocktail Phps 3 (Phps01 + Phps04) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSC3 | ++++ (35 mm) | ++++ (32 mm) | ++++ (38 mm) |

| PSM04 | ++++ (36 mm) | ++++ (38 mm) | ++++ (28 mm) |

| PSM01 | ++++ (35 mm) | ++++ (34 mm) | ++++ (28 mm) |

| PSC05 | ++++ (32 mm) | ++++ (35 mm) | ++++ (22 mm) |

| PSC06 | ++++ (34 mm) | ++++ (36 mm) | ++++ (25 mm) |

| PTCC 1430 | ++++ (40 mm) | ++++ (36 mm) | ++++ (30 mm) |

a Each cocktail is a combination of specific bacteriophages.

b Lytic Activity Symbols: "++++": Very strong lytic activity (clear and translucent plaques).

Efficacy of phage cocktail type 2 (Phps1 + Phps4) against a bacterial cocktail (Pseudomonas aeruginosa and P.gessardii): A, antimicrobial activity of the phage cocktail in pasteurized milk at 4°C; and B, antimicrobial activity of the same cocktail at 25°C. The phage cocktail completely eliminated the bacterial population within 24 hours at 4°C, with no regrowth observed up to 96 hours. In contrast, at 25°C, bacterial counts gradually increased despite the presence of bacteriophages, although levels remained consistently lower than the positive control.

At 4°C, the cocktail eliminated the bacterial population, with no regrowth observed up to 96 hours, demonstrating strong stability and efficiency under refrigerated conditions. In contrast, at 25°C, bacterial counts gradually increased over time despite the presence of bacteriophages, although levels consistently remained lower compared to the positive control. These results highlight that lower temperatures not only enhance bacteriophage stability but also prolong their antibacterial activity in dairy matrices, making phage cocktails particularly suitable for food preservation applications.

4.11. Statistical Analysis of the Lytic Activity of Individual and Combined Bacteriophages

Statistical analysis revealed significant differences (P < 0.05) in the mean lysis zone diameters among the six bacteriophages tested against various Pseudomonas strains. Phages Phps1, Phps3, and Phps4 showed the highest lytic activity, producing clear plaques with mean diameters exceeding 28 mm, significantly larger than those of Phps2 and Phps04. Among the bacterial hosts, PSM01 was the most susceptible, followed by PTCC 1430 and PSC05, while PSC06 and PSM04 showed lower susceptibility. The ANOVA results confirmed a significant effect of bacteriophage type on lytic activity (P < 0.001), and Tukey’s post-hoc test indicated significant differences between Phps1/Phps3 and Phps2/Phps04 in plaque size. A strong positive correlation was observed between bacteriophage host range and plaque size (R = 0.87, P < 0.01). Phage cocktails showed markedly enhanced lytic activity, with inhibition zones ranging from 32 to 40 mm. Cocktail type 2 (Phps1 + Phps4) achieved complete lysis of all host strains, including multidrug-resistant isolates.

5. Discussion

Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas strains detected in dairy products are major contributors to food contamination and represent a growing concern for public health (25). These bacteria exhibit high resistance to commonly used antibiotics such as ampicillin, cefixime, and sulfamethoxazole (26, 27), while their resistance to other antibiotics like meropenem is variable (28). These findings emphasize the urgent need for alternative strategies to ensure food safety and reduce economic losses from product spoilage. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas in dairy products and to evaluate the potential of bacteriophages as a biocontrol strategy. Understanding both the antibiotic resistance profiles and genetic diversity of these isolates is essential for developing effective interventions to ensure food safety.

To better understand the relationships among the isolates, phylogenetic analysis was performed. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that the isolates belonged to P. aeruginosa, P. gessardii, and P. gorinensis. This genetic diversity is consistent with earlier findings that Pseudomonas spp. from environmental and food sources often cluster with both pathogenic and saprophytic species (29-32). In this study, six bacteriophages capable of lysing P. aeruginosa strains were successfully isolated, suggesting that bacteriophage-based biocontrol could serve as a promising alternative to conventional antibiotics in dairy microbiology. These bacteriophages, belonging to the Myoviridae family and confirmed by TEM, demonstrated strong lytic activity and robust infection cycles, which make them effective agents for bacterial control. Among them, Phps1, Phps3, and Phps4 exhibited the highest lytic potential, with Phps1 showing a short latent period and a high burst size, indicating its suitability for further application in controlling Pseudomonas contamination in dairy environments.

The stability of the bacteriophages across a pH range of 4 to 12 and at moderate temperatures demonstrated their suitability for practical applications in dairy processes, where environmental conditions are often variable. These findings are consistent with previous reports highlighting the importance of bacteriophage stability for food preservation (33-35). The demonstrated stability and potent lytic activity of the bacteriophages support the development of phage cocktails as a targeted strategy to enhance antibacterial efficacy and mitigate the emergence of resistance. Experimental results indicated that these cocktails consistently outperformed individual bacteriophages, effectively lysing a broader spectrum of Pseudomonas species. Collectively, these findings highlight phage cocktails as a robust and strategic approach for both commercial and clinical applications aimed at improving food safety.

In this study, the phage cocktails (type 1, type 2, and type 3) were highly effective in eliminating all tested Pseudomonas spp. in pasteurized milk. Our results are consistent with previous studies showing that phage cocktails can significantly reduce P.fluorescens group bacteria in whole, skimmed, and raw milk (35, 36). As reported earlier, combining multiple bacteriophages in one cocktail expands their host range and lowers the risk of resistant strains. What makes our work distinct is that, while most previous research focused on raw or skimmed milk, we demonstrated strong efficacy in pasteurized milk, where spoilage bacteria can still be an issue. Additionally, the reduction of bacterial loads in pasteurized milk at refrigerated temperatures demonstrates their practical applicability in the biocontrol of dairy products. However, the regrowth of bacteria at higher temperatures indicates that bacteriophage application should be optimized according to environmental conditions. Refrigeration enhances bacteriophage stability and antibacterial activity, while storage at room temperature may require additional measures or improved bacteriophage formulations to extend their effectiveness. Overall, this study highlights the promising role of bacteriophages as natural, targeted biocontrol agents against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas spp. in dairy products, contributing to safer food production and reduced reliance on antibiotics.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the presence of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas spp. in dairy products, underscoring their threat to food safety and public health. The successful isolation and characterization of six lytic bacteriophages, particularly Phps1, Phps3, and Phps4, revealed strong antibacterial activity, broad host ranges, and stability across diverse pH and temperature conditions. These features highlight their suitability for application in dairy processing. Importantly, phage cocktails, especially combinations such as Phps1 + Phps4, showed superior lytic efficacy compared to individual bacteriophages, effectively reducing bacterial loads in pasteurized milk under refrigeration. While bacterial regrowth at higher temperatures suggests the need for optimization, our findings support the use of phage cocktails as safe, natural, and efficient biocontrol agents to extend the shelf life of dairy products and mitigate the impact of antibiotic-resistant spoilage bacteria.