1. Introduction

Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is a virus from the Retroviridae family and is classified within the Deltaretrovirus genus (1). Around 10 to 20 million individuals worldwide are believed to be infected with HTLV-1 (2). However, this number has a low confidence level due to the lack of official reports (3, 4). The main known endemic areas are southwestern Japan, the Caribbean, Central and West Africa, and South America. Additionally, HTLV-1 epidemiological studies have shown a high prevalence of the virus in Melanesia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Iran (5, 6).

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) is an infrequent cancer involving the excessive growth of mature CD4+ CD25+ T cells, which results from infection with the HTLV-1 virus. The aggressive forms of ATLL (acute, lymphoma, and unfavorable chronic types) have some of the poorest prognoses among non-Hodgkin lymphomas. In one of the largest retrospective studies, it was shown that the overall survival rate of patients with ATLL was only 14% (7, 8). Due to the rarity of ATLL, conducting extensive clinical trials aimed at detecting and examining novel therapeutic agents remains a challenge. In addition, current treatments largely rely on limited evidence, and the fundamental mechanisms remain incompletely understood (9). Therefore, studies that investigate the genes involved in the pathogenesis of this cancer are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of disease development and to discover potential targets for future therapeutic strategies.

The Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B/mammalian Target of Rapamycin pathway, also known as the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, plays a major part in driving the progression of ATLL. This cellular signaling pathway is key to regulating cell growth, survival, and proliferation (10, 11). In ATLL, HTLV-1 infection can dysregulate this pathway, promoting uncontrolled T-cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis, which are hallmarks of cancer development. By activating this pathway, the virus enhances its ability to evade immune responses and contributes to the aggressiveness of ATLL (10, 12). Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway holds promise for developing more effective therapies by disrupting the survival mechanisms of many cancers, including ATLL, potentially improving outcomes for patients with this otherwise difficult-to-treat malignancy (13, 14). In a previous systems virology study, the hub genes that are differentially expressed in patients with ATLL versus healthy controls and asymptomatic carriers were determined (15). Of them, alpha-actinin-4 (ACTN4), Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 2 (TSC2), C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4), and Activating Transcription Factor 1 (ATF1) exhibited differential gene expression that is associated with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway.

2. Objectives

In this research, quantitative PCR was utilized to assess the expression of these four cellular key genes — ACTN4, TSC2, CXCR4, and ATF1 — associated with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in response to HTLV-1 infection. The expression levels and interactions of these genes were then compared between ATLL patients and healthy controls.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Population

A total of 20 individuals participated in this pilot case–control study conducted between 2023 and 2024, comprising 10 healthy controls recruited from the Tehran Blood Transfusion Organization, Tehran, Iran, and 10 ATLL patients enrolled at Shariati Hospital, Tehran, Iran. The diagnosis of ATLL was confirmed by a clinical hematologist based on World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria. The required sample size was calculated a priori to achieve a 95% statistical power; however, the final number of participants was determined by the limited availability of confirmed ATLL cases during the study period. Participants provided informed consent and were included if they tested positive for HTLV-1 by both enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and PCR, had no concurrent infections with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), or hepatitis B virus (HBV), and no history of other cancers or chemotherapy. Controls were negative for HTLV-1 by ELISA and PCR.

3.2. Sample Collection and Laboratory Analysis

Researchers collected 6 mL of whole blood from each participant in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-treated tubes and transported the samples under cold-chain conditions to the virology laboratory. Serological screening for HTLV-1 was performed using the Dia.Pro ELISA kit (Dia.Pro, Italy) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Optical density was measured at 450 nm using an ELISA microplate reader, and results were interpreted as negative (< 0.9), inconclusive (0.9 - 1.1), or positive (> 1.1). DNA was extracted from whole blood using the DNsol kit (ROJE, Iran), and its quality was evaluated by OD260/OD280 ratio on a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. The integrity of DNA extraction was confirmed through amplification of the RPLP0 housekeeping gene. HTLV-1 infection was verified by PCR targeting the long terminal repeat (LTR) and HBZ genes, following the protocol described in our previous studies (6, 16).

3.3. RNA Extraction and Confirmation

We extracted total RNA from fresh whole blood using the RNJia kit (ROJE, Iran). We measured RNA concentration (ng/µL) and purity using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, with 260/280 ratios near 2 indicating high purity. We removed genomic DNA contamination by DNase treatment before Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis to ensure RNA integrity for downstream applications.

3.4. Complementary DNA Synthesis

Synthesis of cDNA was performed using the RT-ROSET Kit (ROJE, Iran), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction mixture contained 6 µL of nuclease-free water, 10 µL of Master Mix, 1 µL each of forward and reverse primers, and 2 µL of cDNA template.

3.5. Quantitative Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Expression of the viral HBZ gene and cellular genes CXCR4, ATF1, TSC2, and ACTN4 was analyzed by quantitative Real-Time PCR, using RPLP0 as the reference gene due to its stability in human T-cells (17, 18). Messenger RNA (mRNA) from 10 ATLL patients and 10 healthy controls served as templates. SYBR Green Master Mix (Yekta Tajhiz Azma, Iran) and specific primers (sequences and Tm in Table 1) were used. Standard curves were generated using serial dilutions to quantify gene expression (Table 1). Quantitative Real-Time PCR was performed with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 4 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 40 seconds, 60°C for 40 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds. Expression levels of target genes were normalized to RPLP0, and standard deviations were calculated for each sample.

| Genes | Primers (5'-3') | Tm (°C) | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| RPLP0 | 164 | ||

| Forward | GACAAAGTGGGAGCCAGCGA | 61 | |

| Reverse | ACACCCTCCAGGAAGCGAGA | 61 | |

| CXCR4 | 108 | ||

| Forward | ACTACACCGAGGAAATGGGCTCA | 60 | |

| Reverse | TGGAGTAGATGGTGGGCAGGA | 60 | |

| ATF1 | 145 | ||

| Forward | AGTTGGCAAGTCCAGGCACA | 59.7 | |

| Reverse | ACCTGATTGCTGGGCACAAGT | 60 | |

| ACTN4 | 180 | ||

| Forward | ACGAGGAGTGGCTGCTGAATGA | 60 | |

| Reverse | CGTGCTTGCGAATGAGGGCTT | 61 | |

| TSC2 | 60 | ||

| Forward | GGATGTTGGCTTGTCCTCGGAA | 60 | |

| Reverse | TGCAGGGAGACCTCTATGTCCA | 60 |

Abbreviations: RPLP0, ribosomal protein lateral partner; CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; ATF1, activating transcription factor 1; ACTN4, actinin alpha 4; TSC2 tuberous sclerosis complex 2..

3.6. Statistical Evaluation

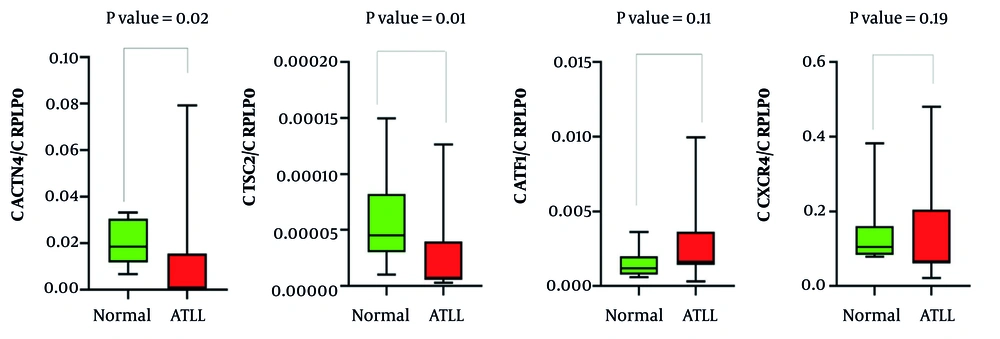

Data analysis and visualization were performed using GraphPad Prism (v9.0.2.263), generating graphs and tables (Figure 1 , Tables 2 - 4). Due to the small sample size (N = 10 per group), normality could not be reliably assessed; therefore, group comparisons were conducted using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Abbreviation: ATLL, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma; human immunodeficiency virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; or hepatitis B virus.

aP-values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test; for age comparison between control and ATLL groups, P = 0.12, indicating no significant difference.

bDescribed in inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Abbreviation: ATLL, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma; CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; ATF1, activating transcription factor 1; ACTN4, actinin alpha 4; TSC2 tuberous sclerosis complex 2.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

| Gene | CXCR4 | TSC2 | ACTN4 | ATF1 | HBZ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CXCR4 | |||||

| Correlation a | 1 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.54 | -0.07 |

| P-Value | - | 0.002 | 0.035 | 0.114 | 0.865 |

| TSC2 | |||||

| Correlation a | 0.88 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.58 | -0.04 |

| P-Value | 0.002 | - | 0.013 | 0.088 | 0.918 |

| ACTN4 | |||||

| Correlation a | 0.68 | 0.77 | 1 | 0.35 | 0.07 |

| P-Value | 0.035 | 0.013 | - | 0.33 | 0.865 |

| ATF1 | |||||

| Correlation a | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.35 | 1 | -0.54 |

| P-Value | 0.114 | 0.088 | 0.33 | - | 0.114 |

| HBZ | |||||

| Correlation a | -0.07 | -0.04 | 0.07 | -0.54 | 1 |

| P-Value | 0.865 | 0.918 | 0.865 | 0.114 | - |

Abbreviation: ATLL, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma; CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; ATF1, activating transcription factor 1; ACTN4, actinin alpha 4; TSC2 tuberous sclerosis complex 2.

a Spearman's correlation

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

A total of 20 individuals participated in this study, divided into two groups: 10 healthy controls and 10 ATLL patients. The average ages were 59.9 ± 3.1 years and 53.2 ± 7.32 years for the healthy control and ATLL patient groups, respectively. No significant difference in age was observed between the groups (Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.12) (Table 2).

4.2. Gene Expression Assessment

The mRNA expression levels of the genes ACTN4, TSC2, ATF1, and CXCR4 were assessed in both healthy controls and ATLL groups. As shown in Figure 1, the gene expression patterns illustrate the differences between the groups. Table 3 provides a summary of the statistical analysis, including mean expression levels, standard deviations, and p-values. The results showed a notable difference in ACTN4 and TSC2 gene expression levels across the groups (P < 0.05), whereas ATF1 and CXCR4 did not show statistically significant changes (P > 0.05). Furthermore, the mean expression of HBZ in ATLL patients was 0.638 ± 0.21, with a maximum value of 1.04 and a minimum of 0.43.

4.3. Analyzing Relationships and Patterns in Gene Expression Data

Table 4 illustrates the comparison of differential expression among the targeted genes, as well as the correlations observed between them. A meaningful positive correlation was found between CXCR4 and TSC2 (R = 0.88), suggesting a synchronous expression pattern between these two genes. Similarly, CXCR4 shows a significant positive correlation with ACTN4 (R = 0.68), while TSC2 is significantly positively correlated with ACTN4 as well (R = 0.77) (Table 4). These consistent associations among CXCR4, TSC2, and ACTN4 imply that these genes may be co-regulated or participate in related cellular pathways, potentially in the context of HTLV infection or general cellular regulation. In contrast, HBZ does not exhibit any statistically significant correlations with the analyzed cellular genes. However, it shows a negative correlation with ATF1 (R = -0.539), though not statistically significant (Table 4). This inverse relationship may indicate a potential suppressive interaction between HBZ expression and ATF1, which could be biologically relevant and may warrant further investigation. The correlations between HBZ and the other genes (CXCR4, TSC2, ACTN4) were weak and non-significant, with correlation values close to zero, including slight negative associations with CXCR4 and TSC2 and a positive correlation with ACTN4 (Table 4). Overall, the data highlight strong interconnections among specific cellular genes, whereas HBZ appears to function independently of these genes in this expression dataset, exhibiting a noteworthy but non-significant inverse trend with ATF1 (Table 4).

5. Discussion

HTLV-1 infection is considered one of the most notable infections in endemic regions. In this study, we investigated the mRNA expression of host factors ACTN4, TSC2, ATF1, and CXCR4, which are involved in cellular signaling pathways. Our results revealed a significant downregulation of ACTN4 and TSC2 and a trend toward upregulation of CXCR4 and ATF1 in ATLL patients compared to healthy controls, highlighting potential molecular changes associated with disease progression.

ACTN4, a cytoskeletal protein regulating cell motility and invasion, is frequently upregulated in solid tumors such as cervical and breast cancer, where it promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), metastasis, and poor prognosis (19, 20). Silencing ACTN4 in ovarian, lung, and bladder cancer cell lines reduces migration and invasiveness (21-24). In contrast, we observed decreased ACTN4 expression in ATLL, suggesting a context-dependent role. This discrepancy may reflect the hematological nature of ATLL, differences between lymphocytes and tumor tissues, or regulatory mechanisms affecting mRNA versus protein levels. Previous inconsistencies in studies of interleukin-17 (IL-17) in HTLV-associated diseases support the idea that sample source, genetic factors, and molecule subtype can influence expression patterns (25, 26) ACTN4’s correlation with TSC2, both involved in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, is particularly notable, though their interaction in ATLL remains largely unexplored. Larger studies and protein-level analyses are needed to clarify these findings and their functional significance.

TSC2 is a critical tumor suppressor that regulates the mTORC1 signaling pathway, which controls cell growth and metabolism (27, 28). In many solid tumors, TSC2 inactivation promotes mTORC1 hyperactivation, tumor progression, and altered cellular behavior, including increased oxidative stress sensitivity and abnormal proliferation (27-32). Interestingly, we observed decreased TSC2 expression in ATLL, suggesting distinct regulatory mechanisms compared to solid tumors. Reduced TSC2 may contribute to ATLL cell survival and proliferation via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and could interact with CXCR4 to facilitate lymphocyte invasion. These findings highlight a context-dependent role of TSC2 and underscore the need for further studies to clarify its function in ATLL and its potential as a therapeutic target.

ATF1, a member of the Activating Transcription Factors (ATFs), regulates gene expression through interactions with cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and influences cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, and inflammation (33, 34). Its dysregulation is linked to several cancers, with elevated expression in lymphomas and activated lymphocytes. ATF1 also regulates matrix metalloproteinases, contributing to cancer invasion and metastasis in solid tumors such as lung and gastric cancers (35, 36). In HTLV-1 infection, the viral protein HBZ binds CREB, ATF1, and CREM-Ia via their bZIP domains, while the Tax protein enhances transcription of viral and host genes, including ATF1 (37, 38). In our study, ATF1 expression was higher in ATLL patients than in controls, though not statistically significant. These findings suggest a complex, multifaceted role for ATF1 in ATLL, warranting further investigation in a larger sample size to clarify its contribution to pathogenesis and therapeutic potential.

CXCR4, a chemokine receptor for CXCL12, regulates proliferation, migration, and survival in normal and malignant cells and is implicated in hematological malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and multiple myeloma, as well as solid tumors (39). CXCL12-CXCR4 signaling activates Ras, PI3K, phospholipase C (PLC), intracellular calcium, and additional pathways including Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT), Wnt/β-catenin, and CaMKII/CREB, promoting chemotaxis, proliferation, and survival (40, 41). In ATLL, HTLV-1 Tax enhances this axis, increasing ERK1/2 phosphorylation and cell migration, which can be inhibited by CXCR4 antagonists (40, 41). In our study, CXCR4 expression was higher in ATLL patients than in controls, although not statistically significant. Limited sample size, biological variability, and complex signaling may explain this. Further studies with larger cohorts and functional analyses are needed to clarify CXCR4’s role in ATLL pathogenesis and its potential as a therapeutic target.

The main limitations of this study include the small sample size, which may have limited statistical power, particularly for detecting subtle differences in CXCR4 and ATF1 expression, and the lack of gender diversity in the study population. Additionally, the gene expression findings were not validated at the protein level, which limits the ability to confirm whether mRNA changes translate to functional protein differences. ATLL is a rare disease, and recruiting sufficient, clinically confirmed cases remains challenging. Therefore, our results should be considered preliminary and warrant validation in larger, multi-center cohorts with more diverse populations and complementary protein-level analyses.

5.1. Conclusions

In this study, although CXCR4 and ATF1 showed non-significant upward trends, a significant downregulation of ACTN4 and TSC2 was observed in ATLL patients. These findings suggest that HTLV-1 may influence ATLL pathogenesis through distinct molecular mechanisms affecting host cellular pathways. The results are preliminary and warrant further investigation in a larger sample size to clarify the potential roles of these genes in ATLL biology. These results provide preliminary baseline data on mRNA expression patterns that can inform future research. Further studies with larger and more heterogeneous populations, coupled with protein-level analyses such as Western blotting or ELISA, are required to validate and extend these findings.